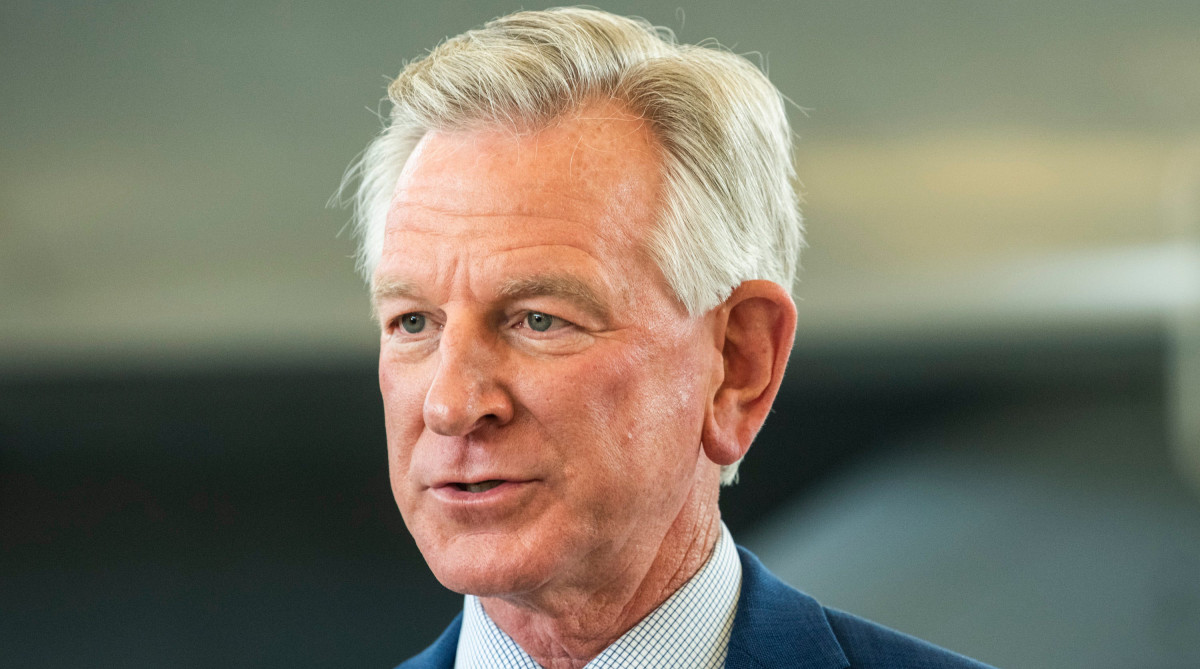

Tommy Tuberville Is Leading the Latest Congressional Push for NIL Regulation

Tommy Tuberville, the college football coach turned U.S. senator, is spearheading the latest congressional movement to regulate name, image and likeness (NIL).

In an interview this week, the 67-year-old Republican senator from Alabama announced his intent to draft a bipartisan NIL bill with fellow senator Joe Manchin, a conservative Democrat from West Virginia. In a letter to be sent this week to stakeholders within college sports, the two senators are seeking feedback on NIL, an unregulated issue that college officials say has created a chaotic landscape in the industry.

A former coach at four schools, including SEC programs Auburn and Ole Miss, Tuberville describes the NIL situation in college sports as a “mess” and a “free-for-all.”

“I’ve talked to all my [coaching] buddies. They’ve never seen anything like it,” Tuberville says. “When you don’t have guidelines and direction, no matter what you are doing, you are lost. They are all lost right now.”

Like Tuberville, Manchin, generally cited as the most conservative Democrat in the U.S. Senate, holds deep ties to college football. He played quarterback for his home-state Mountaineers until suffering a career-ending knee injury. He’s been a close friend with Alabama coach Nick Saban since childhood. Saban even endorsed the senator in a campaign ad that aired in 2018.

Tuberville and Manchin have spoken with Saban about NIL, Tuberville says. Tuberville’s staff also met with SEC commissioner Greg Sankey and Pac-12 commissioner George Kliavkoff in May, when the two men visited lawmakers on Capitol Hill to lobby for legislation.

Saban, as well as many other coaches and high-level administrators, have repeatedly and loudly called for Congress to create a federal NIL solution to override a bevy of state laws that, quite literally, have schools operating by different rules. NIL rules are inconsistent, and enforcement is somewhat nonexistent, officials say, resulting in what they believe is a festering problem: the involvement of boosters.

Big-money donors and donor-led organizations, dubbed “collectives,” are distributing NIL-disguised payments to athletes in what officials believe are inducements to sign recruits, retain players and poach athletes from other teams—an issue that SI explored in a May story.

Though NIL state laws do not vary greatly, some of them have been amended to allow coaching staffs and administrators more freedom in the facilitation of NIL ventures. Other states, such as Alabama, have entirely rescinded their state laws, giving universities in those states more liberties as long as they stay within the NCAA’s vague guidelines released last summer.

“The goal here is to make an even playing field. We want to try to make it as fair in each state so everybody will have an equal opportunity,” Tuberville says. “There’s got to be some rules. Right now, everybody is doing something different. There’s a lot of money being paid. But this is not about the money. I’ve always been for the student-athletes making money. But this is about giving everybody the opportunity on the college level, no matter what university, to feel like you’ve got an opportunity to compete.”

In the letter to stakeholders, Tuberville and Manchin write that Congress “must act to set clear” NIL ground rules as a way to protect athletes, ensure equity in the game and preserve “the time-honored tradition of college sports.”

“We are rapidly accelerating down a path that leads away from the traditional values associated with scholastic athletic competition,” the letter read. The senators refer to NIL as a new “arms race” in college sports that has exceeded the original intent of the ruling from the Supreme Court last summer in the NCAA’s 9–0 loss in the Alston case, a decision that resulted in the further crumbling of the organization’s decades-old amateurism policies.

Tuberville plans to speak to his former players, those active on college teams and even recruits who experienced the first cycle of recruitment in the NIL era. The senator hopes to get all feedback by the end of August and begin drafting legislation as the 2022 football season kicks off. Whether it gains real traction will be another story entirely.

Since 2019, at least eight federal NIL bills have been filed, including proposals from Democrat senators Chris Murphy, Cory Booker and Richard Blumenthal, as well as Republican senators Jerry Moran and Roger Wicker. Despite more than a half-dozen congressional hearings on the topic, NIL proposals in both the House and the Senate have failed to gain enough support to move through either body. In the past, Republicans and Democrats have disagreed on both the scope (broad vs. narrow) and concepts (permissive vs. restrictive) of an NIL bill.

Conservatives have wanted more narrow legislation that focuses exclusively on NIL and includes athlete restrictions and antitrust protections for the NCAA. Liberals have targeted a broad bill that encompasses athlete health care, lifetime scholarships, even revenue sharing and collective bargaining, and provides athletes with more freedoms in NIL ventures.

The two sides came the closest to a compromise last summer, when Senator Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.), the chair of the powerful Senate Commerce Committee, and Wicker worked on bipartisan legislation that ultimately failed. The two sides could not agree on several provisions, most notably long-term athlete health care.

Tuberville and Manchin are in the infancy stage of gathering a framework for their potential legislation, and so it is too early to publicly comment on possible concepts, Tuberville says.

“We are not getting involved with the [NIL] money. We want to get into some rules—who you can give money and how. Something like that,” he says. “We don’t know the direction this is going to take us. We want to come up with something that we can sell to both sides of the aisle.”

The NCAA is hesitant to sanction programs over NIL because the association is “afraid of lawsuits,” Tuberville says, something SI explored.

In May, the NCAA enforcement staff did release a letter to schools emphasizing that it is pursuing potential violations connected to NIL. Not long afterward, the staff visited the University of Miami, where investigators interviewed several people, including booster John Ruiz, who has spent more than $7 million in NIL deals with mostly Hurricanes athletes.

The NCAA spent decades attempting to keep Congress out of college sports affairs, but NIL state legislation, triggered by California and expedited by Florida, sent college leaders to lobby on Capitol Hill in 2019. Many believe this failed three-year fight will continue to be fruitless.

There is little appetite for it in a Congress that is juggling budgetary issues and post-pandemic economic problems, says Tom McMillen, a former legislator himself who is now president of LEAD1, an organization representing the FBS athletic directors.

However, this November’s midterm elections could change the balance of power in a Democrat-controlled Congress. Most within college sports believe that a Republican-controlled Senate would create a more simple path to the passage of NIL legislation. A narrow bill, basically, has an easier shot, they say.

“If you have Republican chairs of committees, it’s different,” says McMillen. “It’s more difficult to get a Democratic agenda through.”

Tuberville says NIL legislation should not be a partisan issue. This is about “helping student-athletes and keeping something very important to our country: college athletics and higher education,” he says.

“This might be impossible, but somebody’s got to try,” the senator says. “If we do come up with something, I’ll stand on the Senate floor and scream and shout.”

More College Sports Coverage: