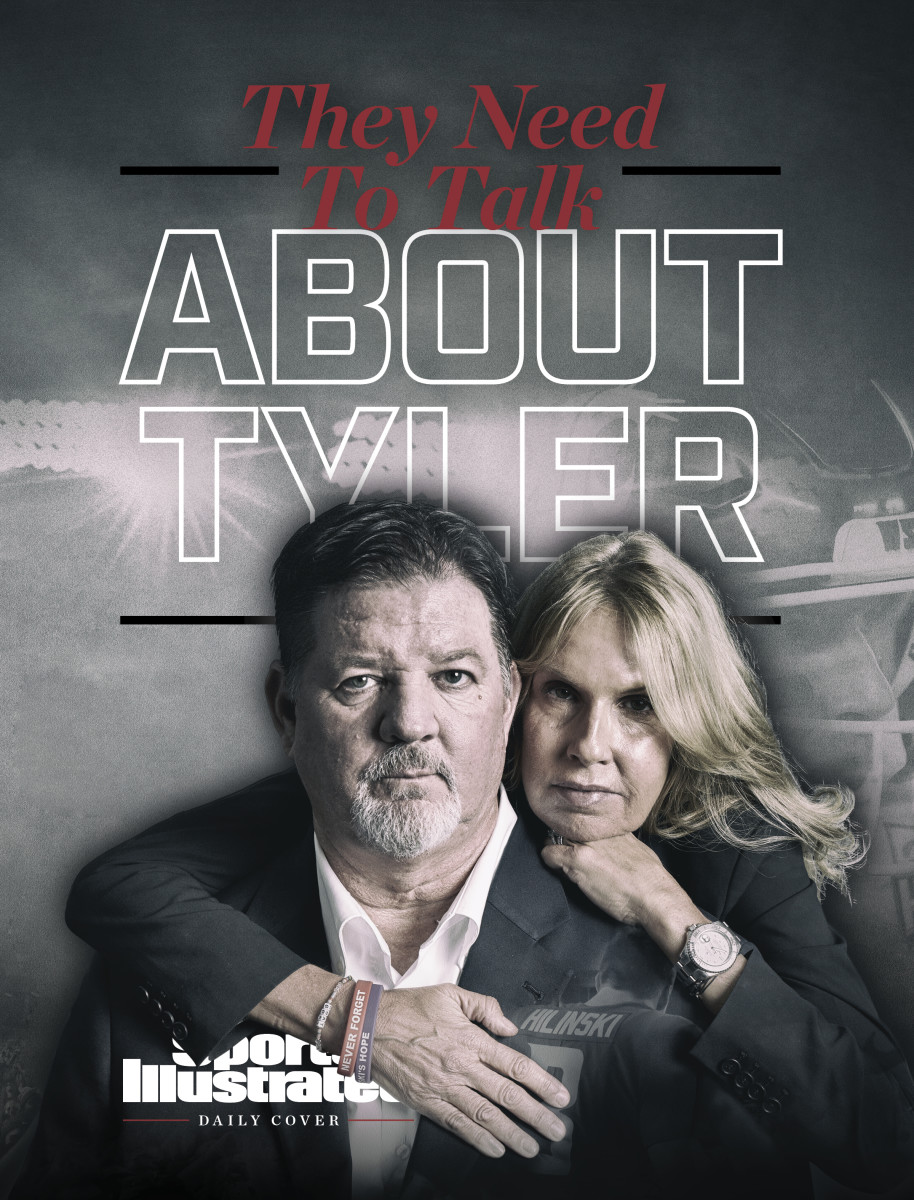

By Talking About Their Son’s Suicide, They’ve Become College Sports Power Brokers—But They’d Trade Anything Not to Be.

Four and a half years after their 21-year-old son took his own life, Mark and Kym Hilinski stand before yet another audience of young athletes with whom they need to share their story, no matter how much it hurts to tell.

Among the 100-odd people seated in Utah State’s auditorium-sized football meeting room is a head coach who earlier this year lost a son to suicide. And one player who attempted suicide and lived. And another who thought about killing himself just this week.

It’s mid-August, but Mark and Kym long ago shoved time into a blender. In the past three years they’ve done 200-plus presentations like this—a mix of PowerPoints and anecdotes, mission statements and video clips, empathy and stats, all addressing what The New York Times has called a mental health “crisis that is only now getting serious attention.” Tyler Talks, they call them.

Mark, 57, is tall and burly. He could give a million of these talks and he would still sigh, still cry, at the same points. His face would still redden. Standing at the front of the room, to the audience’s right, with Kym behind him, he clicks to advance a slide on a projector screen: OUR VISION . . . a world where mental health and wellness will be supported in parity with physical health, and prioritized in connection to athletic performance.

This all sounds great. It’s courageous and critically important. But as Mark and Kym spread their gospel, they also heighten their own pain. It hurts to know that—statistically; realistically—someone in the audience will struggle just as their son did, while accepting that they will never be able to prevent every suicide. It hurts to do this, weeks stretching into years, at the expense of their own family, their own health. And, more than anything, it hurts to relive the worst moment of their lives, retelling Tyler’s story, over and over. Impact and anguish drive each other higher still.

Kym—also 57; also tall, but thin, with blond hair—rises and sits and rises and sits while Mark speaks. She paces. Her eyes wet. To those who know her, she seems to grow ever skinnier, her frame winnowing over the months and years. This is my reality, she tells herself. I don’t know how else to live.

She steps closer to the audience, looks at the athletes and tells them she sees her son in them. She sits down again . . . then stands again, her hands wiping away tears, arms folded, neck bent, frame scrunched up like she’d rather hide. In a room where toughness is expected, half of the audience is crying. Perhaps they can sense it: She endures this pain to give meaning to her son’s death. For Mark and Kym, the cause becomes more urgent, their own lives less so.

They give and give, but some things are too heavy for these talks. Too heavy to say aloud. They have never spoken, for example, about the “strange conversation” they had shortly after their son’s death. Both parents believed Tyler was in some version of an afterlife. Kym liked to imagine him “free of pain” and “being taken care of.” They still had two living sons who needed them, more than ever—but now they were forced to consider: Did Tyler still need them, too? Kym can’t recall who brought up the idea, but eventually they debated whether one of them should kill themself, to join Tyler.

The discussion never advanced beyond that point. They never explored whom or how. “But we did go there,” says Kym, evincing the torment and turmoil they’re still grappling with today.

Instead, they dedicated their lives to two purposes: ending mental health stigmas in sports and caring for their two other children. All that while traveling to universities like this one to save other Tylers, and to save those other Tylers’ friends and families and coaches from the existence the Hilinskis now live.

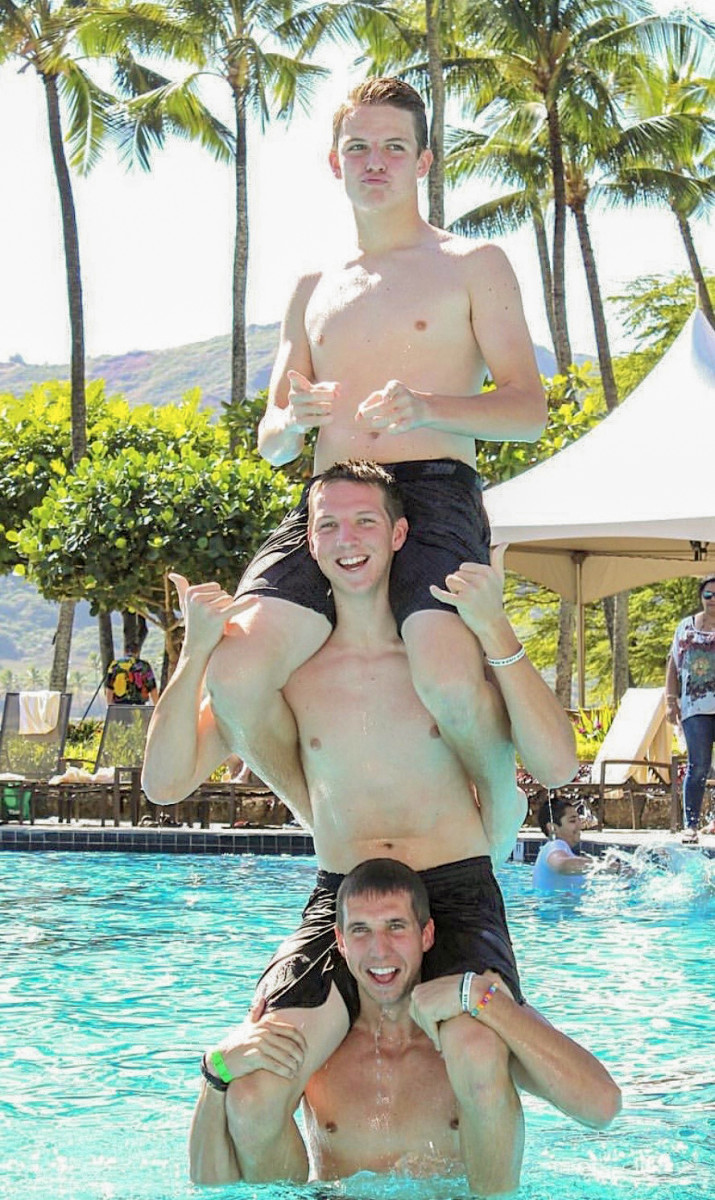

Mark Hilinski was an aquatics manager at a high school in Upland, Calif., more than 30 years ago when he interviewed a college student on her way to law school. Kym Haun got the lifeguarding job and, eventually, the law degree; Mark would go on to start a software company; and they married in 1991, eventually raising three football-loving boys in idyllic Orange County. The oldest, Kelly, played quarterback at Columbia and then Weber State. The youngest, Ryan, transferred in 2021 from South Carolina to Northwestern, where he split QB duties this season before tearing his left ACL and MCL.

Tyler, the middle child, was a backup at Washington State, then a spot starter. In January 2018 he was poised to be named QB1. Instead, he died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound at his off-campus apartment.

Within months, Mark and Kym had started a foundation, Hilinski’s Hope. To raise money and awareness for mental health. To create resources. To erase stigmas. To save lives. They put themselves in front of people often and just talked. They told Tyler’s story, to keep his memory alive. And they stressed, above all, that suicide can happen to anyone and that you don’t need a tragedy to ask for help.

The foundation is built on colleges, because Washington State, like most schools, lacked the resources Tyler needed. (WSU, at the time, had one part-time counselor for an athletic department with 525 athletes.) So now Mark and Kym assist universities in institutionalizing best practices for improving mental health. And, because they’re not licensed practitioners, they connect athletes with experts. All of this, they hope, will save lives.

Mark and Kym now exist in both the past and the future, their lives bifurcated on the day Tyler died. They decided long ago, Mark says, that “it’s better to be lost in this world, trying to help people,” than anywhere else. But, he says, “I don’t know how long we’ll do it for.”

The Hilinskis’ experience speaks to a crisis: A staggering number of young and accomplished athletes are dying by suicide. (More than before? The data doesn’t exist to compare. But, undoubtedly, awareness of these deaths is heightened. People are shaken.) And Hilinski’s Hope speaks to a sea change. More awareness. More resources and support. More of an understanding that mental health struggles should not be viewed as a weakness—in part through the observed experiences of stars across all sports. Simone Biles. Dak Prescott. Michael Phelps. Mikaela Shiffrin.

Naomi Osaka.

And Tyler. There’s no shortage of studies suggesting that his particular ecosystem, college sports, is in particular need of help. From the National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Suicide is the second-highest cause of death for people between 10 and 34. From the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: For those between 18 and 25, rates of suicidal thoughts, plans and attempts are all higher. And from the NCAA: Anxiety, mental exhaustion and depression are twice as high among college athletes now compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Why? Start with still-developing brains. Add in external pressures. Internal expectations. Isolation. Social media and the swamp of negativity it can be. It all creates a world that for many is nearly impossible to navigate.

In positioning themselves to help athletes find their way, the Hilinskis have become both the most recognizable faces of an unthinkable tragedy and, as ESPN recently put it, two of football’s “biggest power brokers and advocates shaping the future.” (The Hilinskis struggle with their place on such lists; they certainly don’t feel like they’re alone in mental health advocacy. They point to other organizations and student-led initiatives, but none match Hilinski’s Hope in terms of programming or scope.)

Mark doesn’t love saying this, but he’s come to the conclusion that, yes, Tyler was distinct, but what happened to him was sadly typical. “F---,” he says, “this happens every day.”

This is the ubiquity the Hilinskis are up against:

• March 2022: Katie Meyer, a Stanford soccer goalkeeper, dies by suicide.

• April: Robert Martin, a lacrosse goalie at SUNY Binghamton, dies by suicide. And Jayden Hill, a track and field athlete at Northern Michigan. And Sarah Schulze, a cross-country runner at Wisconsin. And Lauren Bernett, a catcher at James Madison.

• May: Arlana Miller, a cheerleader at Southern.

They’re each, in some way, Tyler. They’re also each propelling Mark and Kym forward, despite costs that range from money to health to time. That’s the Hilinskis’ trade-off. Those lives versus their own. And those lives always win.

Kym never spent much energy on why Tyler killed himself. She pushed to have his coroner’s report sealed and hid the family’s copy inside of a safe deposit box. But she relives his final hours daily. At night, her mind wanders into darkness, imagining Tyler on the day he died, the emotions that must have surged through him. She always stops as he climbs into a closet and grabs an assault rifle. She can’t quite go there.

Mark had made Why? his mission. He hired a data forensic firm to unlock Tyler’s phone and find his final searches. What he found—How to load an AR-15? Is an AR-15 really fatal?—hardly answered anything, and his quest dented his health but not his sorrow. He put on weight, which exacerbated his back pain, and he argued with Kym and Ryan and Kelly over his daily steps count. Sure, he’d already had a bovine valve inserted near his heart, but, he asked, Does that really matter, after everything?

Each parent could do only what made sense to them. Kym stayed busy, running marathons and putting together care packages—literature about Hilinski’s Hope, but also T-shirts and hoodies and hats and wristbands. She wrote thousands of thank-you notes, to anyone who donated to the foundation. She answered calls from parents desperate for advice on how to deal with a child’s anguish or guilt or sorrow. Meanwhile, she hasn’t visited a dentist in almost five years. She’s gone to the doctor once, after breaking her pelvis in a fall. And Mark understands. When Kym stops, she’s left with her own thoughts. It’s easier to keep moving.

Kym understands Mark’s search, too. He was sorting through his anguish. But even after he started walking more and watching what he ate, she still worried. Their undertaking was exacting a physical and mental toll. When it comes to their foundation, she wishes he wouldn’t say, for example, that their work sometimes feels “so f---ing stupid.”

Mark tries to explain the steep cost of it all: He loves hearing stories about Tyler, but he hates discussing Tyler in the past tense. He wants to be happy, especially for his boys, but he cannot always summon it, which leads to guilt, which lasers his focus on the lives he didn’t change, the kids he couldn’t reach. Which adds up to an unshakable sense of powerlessness.

That particular circle of torture was in full effect in August, between Tyler Talks, when the Hilinskis traveled to Dublin, where Ryan was starting for Northwestern against Nebraska. At the team hotel they handed Ryan a letter, same as they had before every game of their sons’ careers. Inside, this time, Kym also tucked a patch that Tyler had worn during a youth tournament in Ireland, in 2012.

The next day, rushing to the game, the Hilinskis had to remind themselves that that afternoon mattered. “One of the things I miss is we push off talking about the good things,” Mark says. “There’s always more to do.”

Ryan threw for 314 yards and two touchdowns, with the patch tucked under his right thigh pad, in a Wildcats victory. After five unfathomable years—after his brother’s death and after electing not to play for a Pac-12 school because he couldn’t stomach the burden of following Tyler to the same conference—here was, undeniably, one of those good things his dad speaks of. In the brief time Ryan spent with his parents afterward, he said he could feel Tyler with him and would “remember this day forever.”

But Mark sees clearly how the experience was, in some ways, tainted. “It must feel like such a burden for him,” he says. “He’s doing this for his brother. There’s always so much on him. . . . And there’s just an unfairness to that, because Ryan can never have the same level of highs. Nothing is ever as good as before.”

Ultimately, Mark would leave Ireland inspired, wanting to dive right back into the foundation’s work and “take this thing to the next level.” But that high came with a low, as always. The Hilinskis brought a small amount of Tyler’s ashes to the game and sprinkled them near one end zone as Mark blew a kiss skyward—and those 30 seconds, special as they were, drove his mind back to the same place. Man, if only Tyler could have been here.

But Tyler wasn’t there. He wouldn’t be ever again.

“We didn’t win anything,” Mark says.

An hour before their Tyler Talk in August, the Hilinskis’ rental car pulls right up next to Maverik Stadium in Logan, Utah. Blake Anderson, Utah State’s coach, is waiting to escort Mark and Kym inside. It’s 6:33 p.m., Kym notes, and there’s Tyler’s jersey number, 3, repeated, a sign that her son is “saying hi” as they plow ahead.

Anderson guides them to his spacious office, with a view of the field, and as the Hilinskis settle into a black leather couch he begins laying out his last six years in their unfathomable totality: his first wife’s cancer diagnosis, her death, his father’s death, his brother’s colon cancer. Then, in February, his son Cason’s death by suicide.

Cason, like Tyler, was 21.

After the onslaught of tragedies, Anderson implemented “night meetings,” to address everything but football with his players. He began recruiting guest speakers—people like Mark and Kym. At this moment, though, no one’s a power broker. Looking across the room, Anderson and his second wife, Brittany, see just another set of parents trying to figure out a way forward when it seems impossible to summon the energy, the courage.

Anderson informs his guests that a player on his team attempted suicide a year ago. The coach isn’t sure whether this player will approach the Hilinskis but suspects he might and wants them to be emotionally prepared for it.

Anderson says over and over that he doesn’t want to “dive into this stuff” . . . and then he dives back in. The Hilinskis have this effect on people. He tells them that Cason had been the “happiest individual on the planet,” low-key and balanced, revealing nothing at home that raised alarms. Anderson believes his son took his own life because he “didn’t want to burden us.”

Kym gasps. She thinks Tyler felt the same way. Blake and Cason had just spent New Year’s together, everything perfect—much like the vacation Mark and Kym took with Tyler, to Mexico, shortly before he died. Mark points out the parallels. Anderson shakes his head.

“The reality is: We want to think of Tyler in that audience,” Mark says. “And your son.”

The coach worries about his team. “They have seen me really struggle,” he says. “I’m very open with them. I don’t hold back. I tell them that I’m struggling—but I’ve got a great family and great friends I lean on every day.

“I don’t let a lot of people in front of my family,” he goes on. “But I feel completely at peace about you guys being here.”

Silence hangs heavy in the air.

“I’m not at the point where I’m ready to start talking about this,” Blake says.

More nodding.

“I’d argue that we’re not, either,” Mark responds.

As Mark and Kym evolved as individuals in the months after Tyler’s death, so did their combined presence in the mental-health-in-college-sports space. Different approaches led both to the same place—a longing to do something, anything, for as long as possible. They didn’t know what happened to their son, but they did know that there were programs and people with expertise in this space, and that those programs, those people, would have given him a chance to ask for help.

Could Mark and Kym help everyone? No. Anyone? Probably. Maybe they’d find out if they tried. Maybe not.

Their willingness to assist all who asked meant giving more of everything. More phone calls. More Tyler Talks. More care packages. More interviews with media. It took them to Alabama. Georgia. Back to Washington State. Hundreds of other colleges. They met with officials from athletic conferences and school districts and spoke at mental health seminars. They hope they are needed, but they understand that being needed hurts. Their impact is exactly what they wanted. And the personal agony of it all is exactly what those around them fear. Numerous people who know the Hilinskis express some version of the same sentiment: I’m worried about them.

When Katie Meyer, the Stanford goalie, died, teammates reached out to Kym before the news broke publicly, and it dragged Kym back to her own tragedy. (Often, whether an athlete has died by suicide, attempted suicide or considered suicide, someone close to the athlete has reached out to the Hilinskis, sometimes before contacting anyone else.)

When Lauren Bernett, the James Madison softball player, died in April, Kym was stung. There had been a Tyler Talk planned at the school two years earlier, but it was canceled due to COVID-19. She blamed herself, unreasonable as she knew that was.

Rising overall suicide rates—up for every age group in 2021, according to the CDC, with the highest spike among 15- to 24-year-olds—have alarmed her, especially after so many talks. She can imagine the day when someone who sat in an audience listening to them will still die by suicide. “Eventually, it’s going to [happen],” Kym says.

The rewards of the Hilinskis’ mission can sometimes be obvious: emails and text messages and social media telling them, directly, about suicides they have prevented. After every Tyler Talk, it seems, someone approaches and whispers those magical words: You just saved my life. But the other half of their reality is as tortuous as the first is heartening. They don’t see what doesn’t happen. Most of the impact they have, they’ll never know, which makes it easier to see what’s missing rather than what’s there.

So Mark and Kym focus on what feels right. On what mental health practitioners say. And they hang on to the athletes who linger at the edges after Tyler Talks, those desperate to speak truths but uncomfortable sharing in front of a larger group. Many of them reveal details they haven’t shared elsewhere, which is the power and the burden the Hilinskis hold.

Those interactions, Kym says, are gratifying—and yet she realizes how “strange” that sounds. “I’m not happy that anyone is struggling and suffering. But I am happy they are reaching out and getting help.”

What about her? The human being.

“I want to run away sometimes,” she says. “But I look at Ryan and Kelly and all these athletes, and we can’t.”

Instead, they dig deeper, expand.

“Guess who called,” Mark says in September. The NFL, the most powerful league in U.S. sports, has reached out and wants to explore a partnership. He laughs at the absurdity of it all. College football power brokers? Roger Goodell knowing his name? It’s a bit much, this ecosystem, larger than ever and growing.

In telling Tyler’s story, the Hilinskis have unintentionally started an ever-expanding web. Media accounts of Mark’s and Kym’s suffering heightened everything—interest, donations, kind souls who volunteered to help. It wasn’t long before Kym stopped reaching out to others, because they were reaching out to her. She found the sharing—people demonstrating the tools to express their deepest fears and pains—to be cathartic. “Our therapy,” she says.

The number of Tyler Talks has increased each year. Mark and Kym have told Tyler’s story at least 50 times, in 15 states, just since Utah. They’ve spoken in sprawling auditoriums and meeting rooms, even once inside a baseball locker room. They directed a Big Ten soccer player to a campus therapist after she tore her ACL. They assisted a Big 12 football player who was grieving the death of a relative. They found worn-out mental health practitioners at schools with limited resources and set them up in brainstorm sessions with leaders at larger programs who had found solutions.

These connections matter above all else. But growth has meant more of everything. More travel. More time apart from their children. More financial investment. (The Hilinskis, who work out of their home, estimate they’ve spent $250,000 on their foundation already.)

The blueprint they’ve ended up on, with the help of dozens of mental health experts, includes a 100-plus-page “Game Plan,” with six training modules that can be shared with any league or corporation or individual asking for help. An “order of operations” document lays out their process: (1) training for the mental health practitioners who’ll execute their plan; (2) a Tyler Talk; (3) a Facilitator Handbook, for anyone looking to spread the Hilinski’s Hope message; (4) mental health training for athletes; (5) a “scorecard” to help adapt these guidelines to any distinct setting and “implement the NCAA’s Mental Health Best Practices”; and (6) additional training, which is optional.

The Hilinskis also created College Football Mental Health Week, in 2020, at the beginning of October each year. They asked schools and players all over the country to participate—by wearing ribbons or helmet decals; by engaging in training sessions; by simply holding up three fingers, for Tyler’s No. 3, at the start of the third quarter. Alabama joined—Nick Saban made the hand gesture on the sideline. So did Georgia. Clemson. Texas A&M. Even Washington State. Elite programs considered the Hilinskis’ work valuable—they saw what Mark and Kym struggled at times to see themselves.

Participation has ballooned every year: from 17 schools to 65 to 123 in 2022, when the Hilinskis raised $115,000 and made a significant stamp on social media. And now the NFL’s calling—maybe even interested in creating its own mental health week.

The work, Kym says, has saved her life, on those nights when she has no longer wanted to live. But, Mark says, “we have to be real careful about how we count success. We’re still losing 123 people a day [in the U.S.] to suicide.”

The simple fact remains: Mark would still trade “every one of these good things” to “have [Tyler] back for 30 seconds.”

Everywhere they look across the college sports landscape the Hilinskis see signs of change—evidence that more schools are embracing their approach, that more athletes are getting resources. And that combination is likely to save lives.

Take, for example, the University of Nevada.

Ken Wilson, the assistant coach who recruited Tyler to Washington State, happened to be near the Hilinskis’ home in Orange County when Mark called in 2018 to say that Tyler had missed practice. Which was unusual; Tyler never missed practice. A few hours later, Mark called back: “Tyler’s dead.”

Wilson would stay at the Hilinskis’ house that week to help watch over Ryan and Kelly while the devastated parents flew to Pullman. One day later they addressed Tyler’s teammates, and Mark says Hilinski’s Hope was essentially born right there. (Neither Mark nor Kym would return to their jobs after that day.)

Then, last December, following two years at Oregon, Wilson got a call about Nevada’s head coaching job. For the first time in his career he would run a major college program. He would also become a major part of the Hilinskis’ web.

On the first morning of Wilson’s dream gig, his wife, Heather, didn’t say, Good luck or Give ’em hell. She said: “We’re going to start a mental health program.”

They knew exactly who to call. Across Wilson’s 36 years in coaching, he says, “except for the most extreme cases, [mental health] was left in the dark.” Now, in Mark and Kym, he had a remarkable resource. The Hilinskis helped arrange a seminar for Nevada’s coaches, trainers, support staff and administrators; and what struck Wilson was how many of them shared their own struggles. Coaches worried about players and their families. Officials feared an ever-shifting landscape.

The university has since pumped $120,000 into mental health, hiring an in-house professional specifically for athletes, getting others certified in Mental Health First Aid and creating a program to help students communicate when they need support. The athletic department required that all 450 athletes, coaches and staff members complete the Hilinskis’ six training modules.

And all of that happened in less than three months. To Mark and Kym, Nevada is a model, a path forward, a way to apply their blueprint all over the country, others carrying the message for them. (“Sprinkling magic Tyler pixie dust all around,” Mark calls it.) It’s also a window into the Hilinskis’ effect. When Mark and Kym visited for a Tyler Talk, in August, Ken pointed to the blue HILINSKI’S HOPE wristband affixed to his right hand. He had one of the originals. He’d never removed it.

Now, what happens when there are 10 Nevadas? Forty? One hundred? “That’s when the landscape really changes,” Mark says.

They can see it happening, however slowly. From Nevada to Nick Saban to Big Ten commissioner Kevin Warren, who recently told his own story, including the months he spent bedridden as a child after being struck by a car. He, too, created a mental health initiative, in 2020. They can see it in the thousands of college athletes who have signed up for the Hilinskis’ online course. And at Ohio State. When junior Buckeyes lineman Harry Miller retired from college football in March, after revealing his own self-harm and suicide attempts, the school labeled his decision a “medical issue.” That’s important, because it places mental health alongside physical injury.

The way the Hilinskis see it, mental health and performance tie together in so much as victories incentivize decision makers. A tipping point will be reached when others see it the way they do—when resources and dollars committed to mental health are considered central to winning games.

Now imagine more programs like Alabama’s, with its small army of assistants, devoting ample resources to mental health. Best believe that other schools would follow. Conversely, what if a team like Nevada becomes better, faster, stronger than anyone imagined? Then, Mark says, “we have a culture of assistance and help and growth. [That help] is not a burden. It becomes a strength.”

The Tyler Talk in Utah ends. Players stand and clap. Most form a receiving line, from the top of the auditorium stairs all the way to the front, where Mark and Kym wait for whoever might need them.

Some players wrap the Hilinskis tight, like they don’t want to let go. Two, though, linger on the fringes, like they have something they must say in private. One is the player Anderson prepared them for. Kym frees up first, and the player beelines toward her, every step injected with deep purpose. He spares no detail: his anxiety. A car accident that made everything feel darker, untenable, worse.

Soon, he says, it will have been a year since he took a shotgun and fired a bullet through his own chest. He calls it a gift that he survived. He says he hopes to inspire others, but he hasn’t said anything publicly yet. Maybe he’ll make an Instagram video, he says, and tell the world. Kym asks about his parents. “Hanging in,” the athlete says, adding that he speaks to a psychologist.

“It [was] a coin flip, and I got a different result,” he says of his surviving. “I want to keep going.”

Later, Kym huddles with the other player, a lineman who recently became a father. His partner was supposed to have twins, but one of the babies was stillborn. He tells Kym that he considered suicide that week but told no one. Later, he’ll DM Kym of their talk: “Thank you guys so much! You probably saved my life!!!!”

The coin flip and the son, Tyler, who they couldn’t save . . . countered by this Tyler Talk and the athletes they did help. This is the Hilinskis’ reality and their duality—their odd liminal space between unimaginable grief and unwavering purpose. It’s not a choice; it’s the only way they can exist. And those who understand this worry for them. Like Mark’s cousin Jon Welge. In describing the impact of Tyler’s death, Welge uses the analogy of a lightning bolt striking their family tree: The impact doesn’t just splinter the base; it fragments individual branches. “They’re not all going to heal the same way,” he says. If they ever heal at all.

“There will never be a normal again,” says Kym. The planner she carries with her at Utah State is proof, all scribbles and lines and cross-outs and hearts. A trip to Clemson. A meeting with a traveling team of college prospects. Kelly. Ryan. A charity golf tournament. Her cousin’s lacrosse team. The Wilsons.

She starts laughing, because what else is there to do? All this travel, all this work, all this pain—everything tied to whether it’s worth the effort and whether it actually helps, when, the truth is, they will never really know.

“We start settling down in November,” she says, like she’s trying to convince herself.

Is it worth it? Mark and Kym often wonder. And then something happens to suggest it is. Recently, the mother of one of the Stanford soccer players who found Meyer dead inside of a dorm room sent Kym a text message: “She’s smiling and at soccer practice again.”

“I do know that life goes on for everybody else,” Kym says. “Right?”

Then, the other side. Kym mentions Tyler’s friends and teammates. One player—the one who showed Tyler how to use a gun the day before Tyler shot himself—just got married. Kym recently visited Pullman, and this player found her; he said he was devastated and blamed himself. “I can’t be mad at you,” Kym told him.

But happy for him? She wants to be. She is. She thinks she is . . .

“I am happy for those kids,” she says, citing examples of Tyler’s old teammates who’ve since found work in mental health or coaching. Each took a little piece of Tyler with them out into the world. This makes sense to her, and it doesn’t make sense at all. Tyler’s teammates deserve to be happy, to live long and full lives. The thing that complicates it is: So did Tyler.

In recent months Mark’s dedication to the cause only further solidified. But it’s born of despair. After one Tyler Talk, at George Mason in October, he met softball players who knew the James Madison catcher who died by suicide. They were, he says, “as sad as I’ve ever seen a group after our talk.”

“Loss is brutal,” he says. “Loss by suicide has an extra element of fear that makes it incredibly hard for a long time. . . . This is a crisis. This has to stop.”

A week later, Mark sends a picture of another stage, at another school. What else can they do here, besides what they’re already doing?

It’s time for another Tyler Talk.