Family, Football and Forgiveness: C.J. Stroud’s Road to the Playoff Was Anything but Easy

Coleridge Bernard Stroud IV stepped onto the podium, squinted into the camera lights and nestled into his seat behind an array of reporters.

Two days before kickoff of the College Football Playoff semifinals, the centerpiece of Ohio State’s media day was none other than its quarterback, a two-time Heisman Trophy finalist and passing record-breaker that the nation knows by two initials: C.J.

As Stroud surveys the scene at the College Football Hall of Fame in downtown Atlanta, having led his team to the pinnacle of the sport, there is a tinge of disbelief that he is here—not because of some loss on the field to an archrival, but because of so much more.

“It’s kind of, like, surreal to be in this chair right now,” he said. “A lot of times you lose hope and you lose faith.”

Portions of C.J. Stroud’s story have been told, but never the entire tale. That may never be told, its contents too private and personal to be pushed into the public. Maybe one day, C.J. and his mother, Kimberly, will pen a book together about their plight in life, all of it unfolding at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains, a Hollywood story birthed near Beverly Hills itself.

C.J.’s father, Coleridge Bernard Stroud III, is serving a 38-year prison sentence in upstate California. He pleaded guilty in 2015 to charges of carjacking, kidnapping, robbery and misdemeanor sexual battery stemming from a drug-related incident that ended with his evading police by jumping into the San Diego Bay.

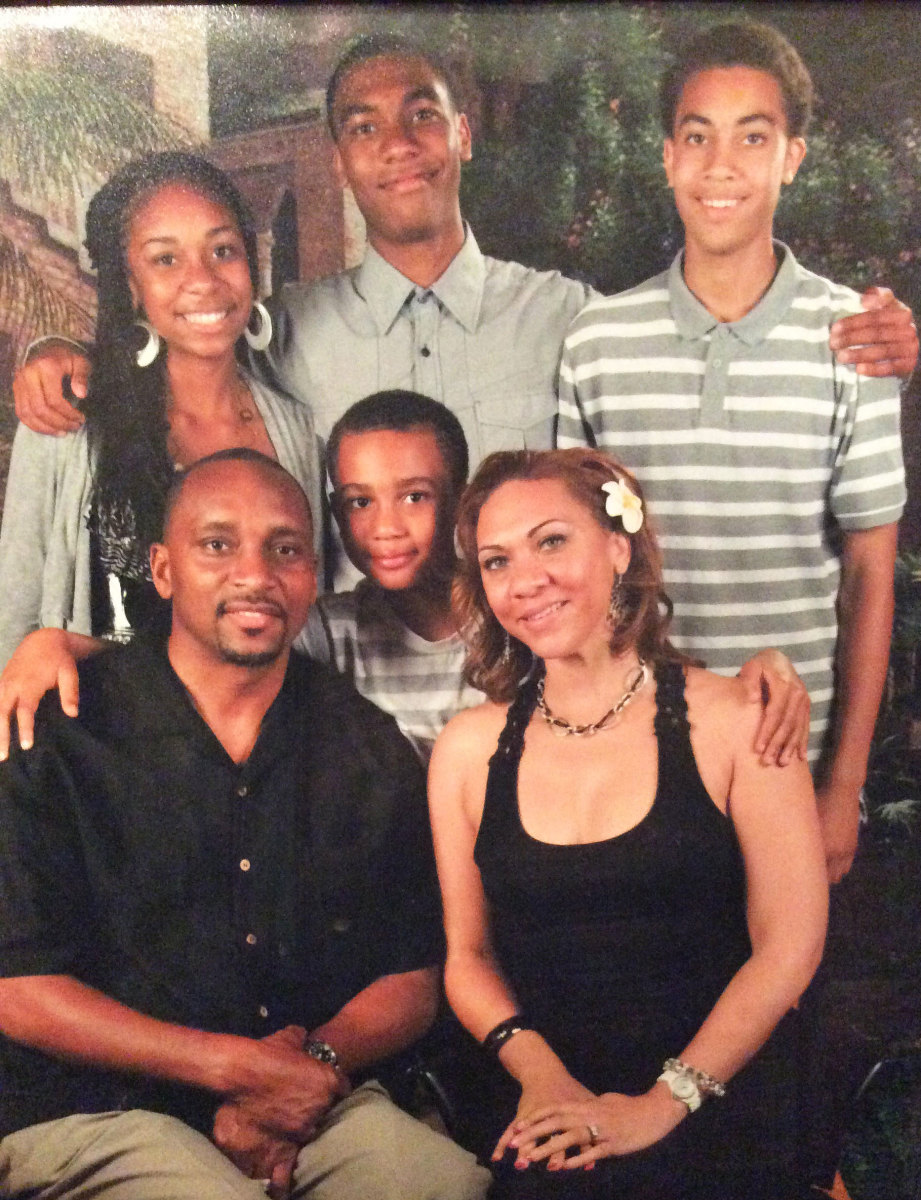

Once a minister and the breadwinner of a family of six, Coleridge’s incarceration (the second of his life) sent the Strouds into financial ruin and destroyed his relationship with his then 13-year-old quarterback of a son. C.J.’s life was rocked by the development. The youngest of four children, his high school years were spent living in a small apartment above a storage facility. At one point, the Strouds nearly went homeless.

As C.J. grew into a talented quarterback prospect, there was little money for new cleats (he got blisters wearing old ones); or new contact lenses (he once played a game without a lens in one eye); or a private quarterback coach (he studied videos on YouTube); or, at times, good nutritious food (his high school often sent the Strouds packaged meals). On the football field, things weren’t much better. C.J. entered his junior season of high school having thrown about 50 pass attempts and had received one scholarship offer.

So on Wednesday, as he tossed passes during practice inside Mercedes-Benz Stadium, C.J. stepped aside for a moment to himself. And it hit him.

“It’s just amazing that I do all these cool things now,” he said.

Cool things: like the $200,000 Bentley he now drives from name, image and likeness (NIL) deals; like the four-bedroom California home he bought his mother and sister; like the $500 Express gift cards he distributed to each of his teammates; like the 13 school passing marks that may forever be his in the Ohio State record books.

And, yes, don’t forget about this—his shot to win a national championship. His team is two victories away from ending the Buckeyes’ seven-season title dry spell and potentially, if Michigan beats TCU in the other semifinal, exacting a level of revenge that few can comprehend.

Given his past, this all seems improbable and unbelievable. Yet here he is.

“He had a choice when his father went away,” says Kimberly. “He was going to let that motivate him and be the best or he was going to succumb to it and become a statistic of a kid whose parent did something they shouldn’t.

“I sit and I’m amazed at how resilient he is. C.J. is the most amazing human I have ever met.”

Willie Munford first saw C.J. Stroud as a 9-year-old.

Little C.J. could throw a pass 50 yards, or about twice as long as most kids his age. C.J. was so tall for his age and threw such a perfect ball—tight spiral, smooth release, incredible accuracy—that opposing youth coaches levied complaints.

“They was saying I was cheating because he was too old,” says Munford. “Slinging that ball downfield like he was, the biggest problems I had then was receivers catching it. He was dropping dimes back then. In 30 years, I’ve never had a quarterback like that.”

Munford coached C.J. for five years, winning two youth league titles. C.J.’s parents were regulars at practice, his dad a vocal and loud influence. In fact, Coleridge first put a basketball and football in his son’s hands. C.J.’s first love was hoops, and while he developed into a star quarterback, he could dunk as a junior high basketball player and eventually evolved into the team’s top shooting guard.

It was C.J.’s deep three-pointer that won a quarterfinal playoff game for his high school team, Rancho Cucamonga, a 3,300-student school located in Southern California’s Inland Empire, about an hour’s drive east of Los Angeles.

Well before C.J.’s high school years, Coleridge became heavily involved in his son’s athletic life. Munford had to often shepherd Coleridge off the sidelines during practices and games. Coach and dad didn’t always agree. Coleridge wanted his son to run more from the pocket. Munford wanted him to remain in the pocket for passing options downfield.

Coleridge was always there, either on the sidelines or the field. And then, suddenly, he wasn’t.

“His dad disappeared,” Munford says.

The coach asked C.J. about his father once and only once.

“He said, ‘I don’t want to talk about it, Coach,’” Munford recalls. “I was going to leave that one alone. He played that year, but he was different. You could tell. He was quiet. He wasn’t playing as normally good as he was supposed to. He still had the arm, but he went quiet.”

On Sunday, April 12, 2015, in downtown San Diego, a man forced his way into the vehicle of a woman stopped at a traffic light. He told her to drive to a house so he could buy drugs, assaulted her and then, after she escaped, fled San Diego Harbor Police in a chase that ended with his crashing the vehicle into a pole and leaping into the San Diego Bay.

This was Coleridge’s fourth arrest and first in more than 20 years. From 1989 to ’92, he was convicted of felony drug possession, receiving stolen property, unlawful taking of a vehicle and armed robbery. For the latter, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

During a 2018 appeal, Coleridge argued in mitigation that in ’12, when his marriage fell apart, “his life spun out of control and he began using illegal drugs again after more than 20 years of sobriety.” The appeal was denied, and his sentence—38 years to life—was upheld.

He has served six years of the sentence at Folsom State Prison near Sacramento and is eligible for parole in 2040. He will be 74 years old.

Coleridge’s sudden absence left Kimberly scrambling to financially support their four children: older sons Isaiah and Asmar, daughter Ciara and C.J., who is seven years younger than Isaiah. She worked at multiple locations as a property manager, moved the family several times into smaller homes and then, finally, was on the cusp of being evicted from a condo unit before accepting a job managing a storage facility in Upland, Calif. As a perk, the family could live in a two-bedroom, one-bathroom apartment above the facility’s office.

“It really saved us,” Kimberly says. “It saved me and my children from being homeless.” It’s not uncommon for the manager of a storage facility to live in an on-site home for security and access reasons. C.J.’s high school coach, Mark Verti, recalls dropping off C.J. at the facility, watching him walk into the office and then up the stairs to the apartment.

C.J. would often have to open the storage facility during after-hours for unit renters.

“He wasn’t always proud to have people over,” says Verti. “He didn’t have the money or the house that most people did.”

C.J. wasn’t afraid to admit it. In a lighthearted way, he’d tell friends and teachers at his school, “I’m broke,” remembers Kelli Cardenas, his guidance counselor at Rancho Cucamonga.

“I remember one time driving with my kids in Upland,” says Cardenas. “I pointed out the storage unit, ‘That’s where C.J. lives.’ My kids couldn’t believe it. They saw C.J. as this big star.”

C.J. didn’t seem to care. He never really asked for much, his mother says. In fact, Kimberly recalls one game in which she noticed her son closing one eye to throw passes. He later told her that one of his contact lenses had worn out and he was afraid to ask her to buy more.

“I’m like, ‘Why didn’t you tell me!?’” she says. “He’s like, ‘You have enough on your plate!’” Later on, coaches raised money to buy C.J. a year’s worth of lenses. “It took a village,” she says.

C.J. wasn’t like a lot of prized quarterback recruits. He didn’t start as a freshman or a sophomore, biding his time behind a more veteran quarterback. He’d have bad days, both for football and family reasons.

At school, he wasn’t playing. At home, his father was gone.

“I grew up without my father,” says Tony Wilson, an assistant coach at Rancho Cucamonga who grew close to both C.J. and Kimberly. “To have a father and then not have him, that’s even worse.”

C.J. persevered, remained at the school and started as a junior and senior, piling up yards, touchdowns and scholarship offers. Before his senior season, Ohio State coach Ryan Day called him with an offer that brought him to his knees and to tears.

The powerhouse programs had finally found this gem tucked in Southern California.

“He didn’t have a lot of clothes or shoes. He didn’t have the private QB coach or the 7-on-7 teams,” says Verti. “He didn’t have extra protein shakes or energy drinks. He did it all himself. He watched YouTube clips on Drew Brees and made himself better.”

For more than five years, C.J. Stroud did not speak to his father.

He didn’t talk publicly or privately about him, either. Only in the past several months has C.J. decided to discuss Coleridge Bernard Stroud III. During a wide-ranging interview with The Pivot podcast, he detailed the hurdles of his life, many of them brought upon by a man that he refers to as “Pop.”

C.J. described his life as a “roller coaster” and as having endured “hell and back.”

“My pops, he was my best friend, to have your best friend be snatched like that, it was tough,” he said. “I just look at the things my dad did that were positive, but for a while, I wasn’t like that. I hated my pops, for real. Like man, how could you leave me like that?”

C.J. and his father were so close that Coleridge, while speaking on the pulpit as a pastor, would involve his son in his sermons, often asking him to speak to the congregation himself.

The last time C.J. saw his dad was either 2014 or ’15, Kimberly says. Coleridge would show up in spurts and then be gone again for weeks at a time.

“When C.J. was in seventh and eighth grade, we really saw the change. [Coleridge would] come and look terrible and C.J. …” Kimberly pauses, “it made him feel so bad. When his dad would come, C.J. would leave.”

C.J. ignored calls, messages and any other communication from the prison—until somewhat recently. Roughly two years ago, C.J. and his father spoke by phone. They now talk intermittently.

After the 2022 Heisman Trophy ceremony, where Stroud finished third in the voting, Coleridge called his son, and they talked for a while, Kimberly recalls. Son has forgiven father.

“When I talk to him now, I don’t hold any ill will,” C.J. said on The Pivot. “I told him, ‘I love you.’ He made his mistakes. I’ve made mine. It’s not about the bad.”

After he completes this season and before he begins preparing for the NFL draft—he’s projected as a first-round pick when he declares, as many expect—C.J. will visit his father in person at Folsom State Prison, Kimberly says.

It will be a long-awaited, complicated and possibly awkward reunion of son and father.

“He’s so proud of C.J.,” Kimberly says. “After the Heisman [ceremony], C.J. is sitting there disappointed in the car, and his dad calls and they talked. At that time, that’s when I knew he forgave his dad.”

Kimberly believes that her ex-husband will be released from prison earlier than expected. His life sentence was tied to California’s Three Strikes law. He’s hired an attorney who is fighting for his release by arguing that at least one of his past convictions—his second strike—should be dismissed, because it was not a violent act.

“They are projecting that he will be released,” she says. “It’s just a matter of the filing and paperwork.”

Meanwhile, 2,500 miles across the country here in Atlanta, C.J. Stroud is preparing for the biggest game of his life. It follows the second-biggest game of his life, when the Buckeyes lost at home to Michigan, 45–23, in a stunning upset that triggered outrage from fans.

C.J. received death threats, his mother says.

“I don’t really look, but people have the audacity to call and talk to me and tell me what people say,” C.J. said Thursday. “It’s the nature of the beast. You accept the good with the bad. I thank God for a second chance at this game. We deserve to be here regardless of what happened that day.”

As C.J. spoke to reporters at media day, his mother, sister and brother Asmar boarded a cross-country flight to watch him play Saturday night when the No. 4 seed Buckeyes (11–1) meet the No. 1 seed Georgia Bulldogs (13–0). The winner plays in the national championship game at SoFi Stadium, a sparkling new $6 billion venue that sits about 50 miles from C.J.'s home.

Georgia, interestingly enough, finished second among his options during the recruiting process. C.J. visited Athens, and coach Kirby Smart visited his home in Upland, walking into that tiny apartment above the storage facility.

“They all came to the storage facility,” Kimberly says with a chuckle, now able to laugh about it. “I told them, ‘I know this is a first for you! Bet you’ve never been to a storage facility to visit a player!’”

Most of them smiled back at her, “Ma’am, we’ve seen a lot. But never this.”