You Can Triple-Team Aliyah Boston—But You Can’t Shut Down Her Brain

It’s winter on the mainland, and Aliyah Boston—reigning National Player of the Year and pride of St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands—is sitting in South Carolina’s practice facility, explaining how to get a taste of the Caribbean. What matters here is not her chosen restaurant (Reggae Grill, a Jamaican place just outside Columbia) or her standing order (curry chicken with a side of mac and cheese), but the way she gives directions:

“You’re gonna see a stoplight. You’re gonna drive over the bridge,” she says. “There’s going to be a gas station—it might be a Shell—to the right. There is gonna be a big Cayce sign to the left. Make that turn; you’re gonna drive; it’s a school zone. And then once you see the little colorful mural, you’re going down two streets and then make a right … there’s gonna be one stop sign … and then it’s going to be to your left. The building is yellow.”

A quick drive later confirms she is correct about all this (and it is a Shell). But does she, um, know the name of the streets?

“Nope,” she says, laughing. “Not one street.”

Give Boston a map, and it might as well be in a foreign language. Ask Boston to memorize a page of text, and she has no chance. But send her on a winding drive with numerous turns just one time, and she can do it again and again. Once, she had to prepare to answer a big, complicated question for a class. Her classmates studied how to complete the problem. Boston just drew the diagram from memory and got an A.

Basketball is an anticipatory sport. Some players sense where the action is going—an intuition that they can’t quite explain. That’s not Boston. Her feel for the game, she says, is good but not exceptional. What separates her is her visual memory. If she has seen anything once, she has seen it a thousand times.

All players watch video clips. Boston’s brain creates them. Every play leaves a permanent impression on her brain. When she watches film of an upcoming opponent, she easily stores all the images and then cuts and pastes them onto the court during live action. The only way for opposing coaches to counter this would be to draw up a never-before-run play on every single possession—which is, of course, impossible. She says, “I remember everything that happens on the court and I can see it all happening, too.” It is a skill that got her here, and that she has needed all season long.

From the start of her senior year, Boston has played on the best of teams and the worst of terms. South Carolina began the season at No. 1 and somehow improved from there. It outlasted then No. 2 Stanford in overtime in Palo Alto and then started whipping just about everyone it played. The Gamecocks are 32–0 heading into their NCAA tournament opener against Norfolk State.

The 6'5" Boston is a dominant physical specimen; her coach, Dawn Staley, who has coached most of the world’s best players leading the U.S. women in the Olympics, thinks Boston will be one of “the top five” most powerful players in the WNBA the moment she is drafted. She also has a soft touch and smooth finishing ability. She is obviously capable of scoring 30 points against anybody, which is why she never does.

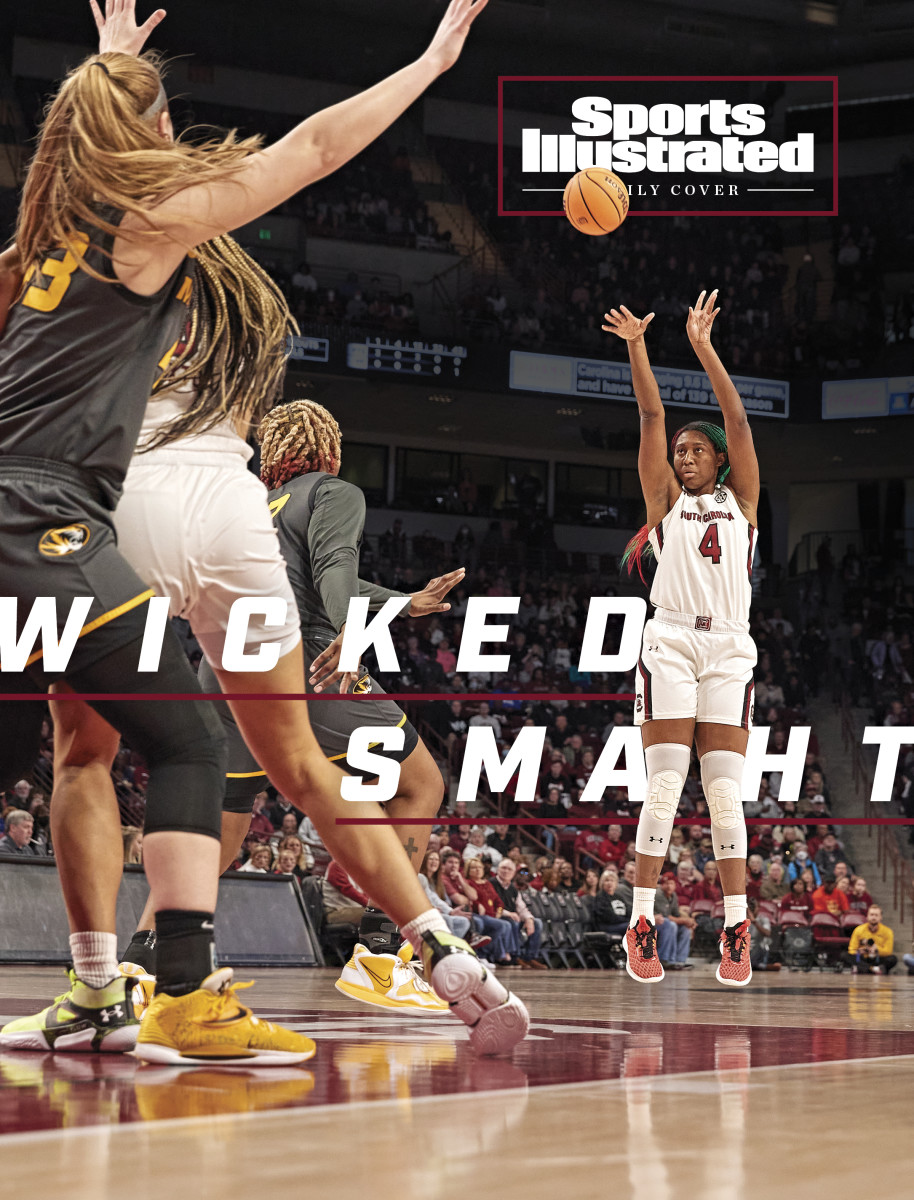

Players get guarded, stars get double-teamed and Boston gets mobbed. This scene is so customary that it starts to seem normal, but of course it isn’t: Boston sets up on the block with an opponent behind her, trying futilely to hold her position … and, because everybody knows it is futile, another player fronts Boston … but because she is still Aliyah Boston, South Carolina passes her the ball anyway … at which point a third and sometimes fourth player collapse upon her. Yes: sometimes a fourth player. South Carolina’s video clips look like cartoons.

“No one else demands that kind of attention,” Staley says. “And actually, people are pretty good at executing it. They’re committed to it. … If I’m somebody else, I do the same thing. You single-coverage her, it’s over. I mean, it ain’t a ball game. It ain’t fair. So they have to do that. You have to beat her up.”

Boston, who averaged 16.8 points on 11.9 shots per game last year, has played most of this season knowing she would never match those stats. (She averaged 13.3 points on nine shots per game.) But her mind has helped her get through it, in two ways. One is that she remembers exactly how each opponent used to guard her: “Last year was not like this at all.” The other is that, even when she doesn’t have room to shoot, she can help South Carolina dominate the game by directing her teammates.

Staley says she has never seen anything like it, and this is a woman who has won two national titles and coached reigning WNBA MVP A’ja Wilson in college. “A’ja ate,” Staley says. “She ate real good from the midrange. Double-teamed? Yes. Not this.”

Staley swears that Boston is a better player than she was last year, when she won the Naismith, Wooden and Final Four Most Outstanding Player awards. Opposing coaches know Boston will beat them, so they commit to making someone like guard Zia Cooke, center Kamilla Cardoso or forwards Laeticia Amihere or Sania Feagin beat them—which they do. Staley says, “It prolongs the loss, I guess, if you want to say it like that.”

Boston’s dominance has led Staley to employ some weird strategies. She thought Georgia had built so much of its game plan around stopping the forward that the best way to throw the Bulldogs off their game was to put Boston on the bench for a longer stretch than usual. So she did.

“She’s unable to work on being a pro with the defenses that are being played on her,” Staley says. “She’s never gonna see a triple team on the next level. Ever.”

Boston has gotten used to what she calls “the two-hand grab,” which is exactly as it sounds: an opponent literally using both hands to grasp any available piece of her, like a fan hoping to leave with a souvenir. A patch of jersey, a forearm—grab what you want, folks! Boston says, “Some of the teams, they’re not really worried about careful. They’re not really worried about … Oh, well, I’m gonna box her out, but I’m going to be aware of her legs or I’m going to be aware of her knees. No, they’re just thinking, She’s not going to get this.”

There are rules to prevent such maulings, but they don’t always seem to apply to Boston. Basketball officials have long struggled to handle large, mobile players. The physics are confusing. If a Nissan Leaf rams into a truck, the Leaf gets destroyed, so who wants to blame the driver of the Leaf? Staley says, “She gets fouled the most that’s not called. How about that? We got our own little category.”

Boston could push players back, but she knows refs would call fouls on her: “They always see the second one.” Boston’s mother, Cleone, has long urged her to flop: “I would tease her at times and say, ‘Aliyah, you barely touch some of these children, and they fall. You don’t want to try just falling once in a while?’ She’s like, ‘Mom. Not gonna happen.’

As for the refs … “They’ll tell the opposing team, ‘Relax in there,’” Boston says. “I’m like, ‘Well, you could just…’”

She forms an O with her lips and makes a blowing sound.

It has all added up to a strange senior season. Boston is a near-certainty to go No. 1 in April’s WNBA draft. (The Indiana Fever own the pick.) She has already won a national championship, her team is favored to win another and she is the biggest reason why. Boston should be having the kind of season that people talk about for years, and instead, as assistant Fred Chmiel says, “She’s the returning National Player of the Year and she’s getting eight shots [a game].”

Boston admits it bothers her at times, but she says, “I know what’s happening. I know how I’m being played. And I know how our team is.” March could provide a sterner test of the defensive strategy and her poise in dealing with it. For now, the visual wizard has taken her social media apps off the home screen on her phone, so she doesn’t see anybody talk about her “declining” play. It helps that in her toughest moments, she can remember exactly how she got here.

When Aliyah was 12, her parents sent her and her sister, Alexis, to Worcester, Mass., to live with their aunt Jenaire Hodge, “because I know my sister the way I know myself,” Cleone says. “She’s the best.” The goal was simple, and it was shared: to earn college sports scholarships. Cleone says the move was painful: “When Alexis and Aliyah were on St. Thomas you couldn’t look around, left nor right, and not see me with them.” Aliyah’s father, Al, still says with a laugh he wasn’t consulted on the decision, a running joke in the family that may feature a kernel of truth.

The decision was certainly unconventional. But it was ultimately successful (Alexis played basketball at NAIA Thomas University), and it shaped Aliyah in ways that nobody could have foreseen at the time. The Bostons managed the trick most parents of teenagers struggle to accomplish: They let their kids go and still held them tight.

“I had points when I would just call [Al] crying,” Cleone says. “Easter came around, and I was in tears. I’m like, ‘I need to see the girls.’ And he was like, ‘Go ahead.’ And I bought a ticket and I was in Massachusetts for the weekend. No special plans. I just needed to be there.”

In St. Thomas, Cleone used to pray with her daughters every morning before school and decided they would keep doing it, even if that meant calling them at 5 a.m. The girls were required to call—not text—back. After a while, Aliyah and Alexis got comfortable in Massachusetts and stopped communicating as quickly with their parents. Cleone deleted the data plan from their phones until they started calling back more. (Even now, she will call Aliyah at 7:30 a.m.; Aliyah puts her phone on “Do Not Disturb,” but Cleone has figured out that she can override that by calling multiple times. They talk every day.)

Al would call Aliyah (the family calls her Peaches) to talk basketball, and that is when Aliyah realized she had this gift: She could recite exactly what happened on plays, with a level of detail that started to strike her as odd.

“She had like a photographic memory of games,” Cleone says. “She would explain the entire play, why it transpired the way they did and what happened.”

Unlike many prodigies, Aliyah did not feel like her athletic prowess made her the center of the universe. She is well aware of what her mom and dad had given up for her. Chmiel says: “Aliyah has the weight of the world on her shoulders, but you would never know it.” She is conscious of her parents’ sacrifice but not burdened by it.

“What impressed me the most wasn’t the changes that I saw,” Cleone says of Aliyah’s time in Worcester. “It was the things that remained the same. She still was the same kind-hearted person. She still was the girl whose friends would not be the stars on the team. They would be just the kids in the school that you wouldn’t normally find in the company of the stars.”

Boston still has a champion’s will and a caretaker’s heart. After one game this season, a fan asked Chmiel to find Boston so she could sign a picture for her son. Boston had gone home. Chmiel offered to take the picture to her and have her sign it. When he brought it to her, she looked at the photo, recognized the boy and said, “I take a picture with him almost every game.” She happily signed another. When freshman Chloe Kitts showed up as a midseason enrollee this winter, it was Boston who sat with her on a bench after practice and went through plays with her. “Nobody asked her to do that,” Chmiel says. “She’s trying to help the kid get acclimated, trying to help her learn the offense, so she can be a more integral part of the team.” On Christmas, Chmiel texted all the players to wish them a merry Christmas. Boston is the only one who texted him first.

Boston was a top-three recruit out of high school, but even then, the Gamecocks did not quite realize what they had in her. Staley says, “She didn’t show us anything extraordinary during the recruiting process, physically. Her presence, obviously. [But] she didn’t get the ball a whole lot. She wasn’t great at making layups.” What Staley noticed early was Boston’s mouth. She was always talking to her teammates: encouraging, cajoling, advising. Though Staley didn’t fully understand it, Boston was perpetually sharing the wisdom that comes from her most unusual mind.

“The reason most kids don’t talk is because they don’t know what to say,” Chmiel says. “She always knows what to say.”

There are downsides to her genius. Boston has never watched her missed layup at the end of a national semifinal loss to Stanford two years ago, but she sees it vividly all the time in her head.

“It’s very, very, very hard,” Boston says. “Sometimes I get annoyed, because things linger in my head. I wish I could, like, fix it. If I know that I didn’t do something right, I just see it over. And I’m like: Why didn’t I just do something else? Why didn’t I just do something else? Why didn’t I just do something else? Everything is always processing.”

Opponents see a physical talent who requires triple teams. Fans see a player who could score much more but doesn’t. But don’t just watch. Listen. “I’m afraid of what the gym’s gonna sound like next year,” Staley says. “I really am—for our team. I am afraid because she covers up a lot for everybody.” All that attention, all season long, and Aliyah Boston is still the reason her team dominates. Elbow her, hack her, send help from the wings. You can never shut down her brain.