When Madness Meets Mesh: Inside the NCAA Tournament’s Football-Inspired Inbound Plays

NEW YORK—Picture this: Your team’s up a few points with time ticking down. You know the opponent is about to foul, and they know that you know they’re going to foul. Your best free throw shooters are on the floor and it’s time to ice the basketball game and get out of the building with a victory. For Kansas State and FAU, that means it can be time to play football.

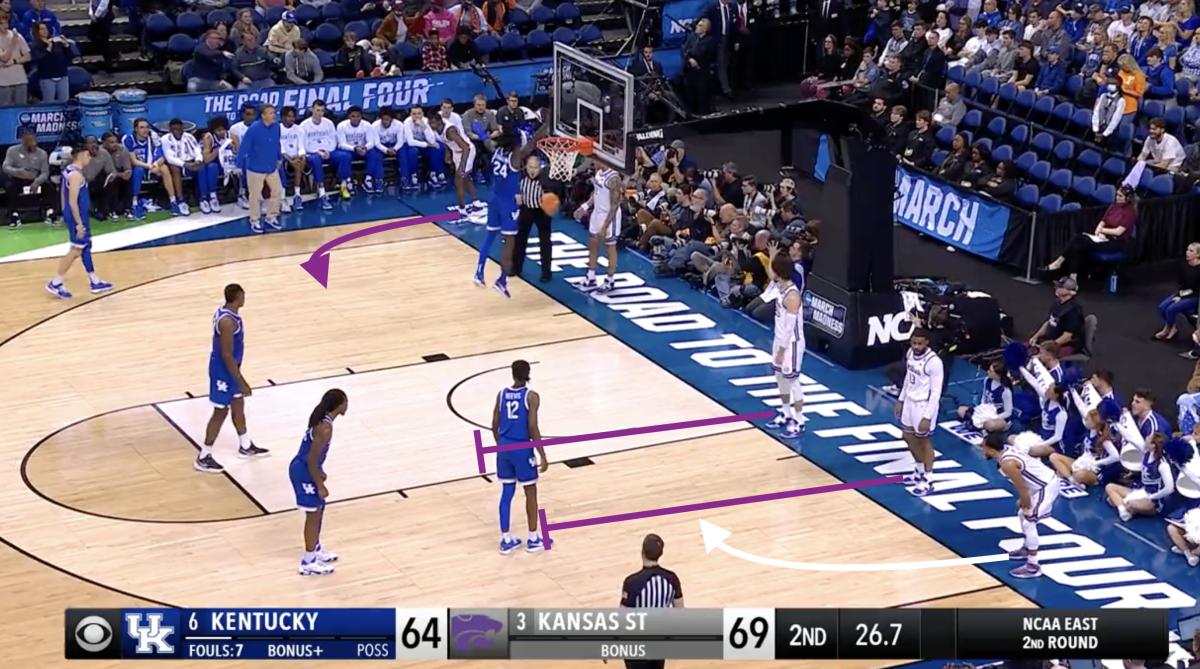

That’s what the Wildcats did to inbound the ball to guard Markquis Nowell late in their second-round win over Kentucky.

Jerome Tang drew up a bubble screen on the inbounds play 👀

— NCAA March Madness (@MarchMadnessMBB) March 19, 2023

Kansas State calls it “Mahomes” 🔥 @PatrickMahomes #MarchMadness @KStateMBB pic.twitter.com/FvABhmYmE2

Nowell caught the ball on what K-State football coach Chris Klienmen would call a “now screen" or bubble screen out of a 3x1 set. Two players screened for Nowell who quickly caught the ball and got fouled on the front side of the formation with guard Cam Carter on the backside to receive a pass just in case.

It’s fitting that the Wildcats play in the Big 12, which has been at the cutting edge of the screen game in football over the last two decades and has now pivoted its conference identity to lean into basketball with Texas and Oklahoma leaving next summer. But K-State wasn’t the only team playing football during March Madness’s opening weekend. FAU ran a similar play that’s straight up air raid in nature, mimicking the play mesh, which was popularized by Mike Leach and is now all over the field on the college and pro levels.

Florida Atlantic running Mesh! pic.twitter.com/6UYzdXZySO

— Coach Dan Casey (@CoachDanCasey) March 20, 2023

The Owls actually have an in-breaking route come underneath the mesh point.

“We ran it for a few years at Baylor, so when I got here I didn’t want to call it what we called it there,” says Jerome Tang, K-State’s head coach and a former Bears assistant. “At Baylor, we called it ‘football.’ Then we ran “‘occer’ when you couldn’t be out of bounds because it was a dead ball, you can only [have all five players] out of bounds after a made bucket. So when we got here, it was ‘who is the best football player?’ Patrick Mahomes is in Kansas City right there, so we called it ‘Mahomes,’ and when we run the other one we call it ‘Messi.’”

It has gotten the attention of the two-time NFL MVP, in addition to color commentator Jim Spanarkel, who was quick to call it a “nice play” on the broadcast.

Just like with any football play you see on a Saturday, the plays being called in 2023 are the end result of a game of schematic telephone. Tang and his old boss Scott Drew found the play while watching a Northern Kentucky game back in 2019. Former Northern Kentucky head coach John Brannen told TexasBasketball.com in a 2019 interview that he stole the play from a friend coaching Illinois State after watching a Redbirds game and called it “Clemson”. Baylor ran a version that was more like football’s four verticals shortly after, fitting for the Bears’ recent history of high-flying offense.

When you run out of inbound plays, so you tell your team to run football routes... Sign them up @CoachMattRhule! #Baylor pic.twitter.com/k7dGWWdxY8

— John Elizondo (@johndelizondo) January 20, 2019

“We’ve worked on it all year long, we’re just waiting on the right time to pull it out and I felt like that was the right time to pull it out,” Kansas State guard Desi Sills says. “Markquise told coach to pull it out and he pulled it out his bag and it worked. We made our free throws every time we got fouled.”

Even though it looks simple, asking any player on either team how the basketball versions work forces them to immediately play media relations defense.

FAU’s Jalen Gaffney wouldn’t even say what FAU’s version is called (his coach Dusty May later told Sports Illustrated it’s called “pigskin”) and Sills declined to talk about the finer points of their play because “we can’t tell you the secret sauce.”

May called the Owls’ version after the team had some trouble getting the ball inbounded against FDU.

“I’ve never played football, but I watched a lot of the Colts when they had Peyton Manning and Reggie Wayne and Marvin Harrison and they ran all those pick routes,” May says. “I remembered some form of pick route that I’d seen and it came out of nowhere.”

It seems simple in the execution, but Tang says one of the reasons this type of play is effective is because teams don’t spend much time practicing how to guard this type of inbounds play. In football, you could defend the Kansas State version with a mixture of play recognition, having a numbers advantage, and using raw physicality to blow the blocks up. For FAU’s, it’s built to exploit man defense on the gridiron, and if you’re playing zone, you’d better communicate how to switch responsibilities quickly.

“Sometimes they sit back which makes it easy to get it in,” May says. “As an offensive coach, you’re worried about the spacing if they do get it in, and there’s all those players still in the frontcourt and there’s no space to make a play. I think defensively the next step is probably to jam the receivers like you would in football if you have a big time receiver in man coverage, you jam him up. I think that’s the next wave of defense on it, but those things aren’t run enough to really.”

For now, in specific late-game situations, expect some football to creep into your basketball from time to time because at the end of the day, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

“It works every single time that we run it so I’m glad we run that play,” Gaffney says.