As Unconventional Underdogs, LSU Relished the Chance to Prove Everyone Wrong

Less than two minutes into the first quarter of the national championship game, Flau’jae Johnson entered the huddle close to tears.

The LSU freshman point guard had drained a three to score the first points of the night for the Tigers. But she had also turned the ball over twice. After a third team turnover, LSU coach Kim Mulkey felt she had no choice but to bring her team in and call an early timeout. They’d played just 97 seconds, and the score was Iowa 7, LSU 3.

Then the Tigers looked at Johnson.

Are you crying? It’s the first quarter; we’re down by four points, and you’re crying?

“Our team had her back,” LSU assistant coach Gary Redus II says. “They all started laughing, going, What’s wrong with you?”

There are some huddles where laughing at a crying teammate may not be the best motivation. But LSU knew: This was just what Johnson needed. They’d had to get to know one another quickly—Johnson is one of nine players new to the team this year—but they’d soon built an understanding. For this team, trash talk is a love language.

Their roster had been unusually constructed, a hodgepodge of transfers and freshmen and second-chance-takers. They’d bonded through swiping at one another on the pickup court. One of their best tournament performances came the day after Mulkey walked out of practice. Mostly, they liked the feeling of being an underdog, and they loved the chance to prove others wrong. And their coach knew it.

Which meant that even in the biggest game of their lives, the first trip to the national championship in program history, Mulkey let them have a few seconds to razz the freshman.

Johnson settled in for the rest of the night. (“To be able to bounce back from that,” Redus says, “it shows you the kind of tough kid she is.”) The rest of the team locked in alongside her. They’d known ahead of time they would not easily be able to shut down the most potent offense in the sport in Iowa, or the most electric scorer in the game in its star junior, Caitlin Clark. But they believed they could find a way to blow past the Hawkeyes. If they were going to dare the Tigers to shoot from outside? Fine. They loved a dare.

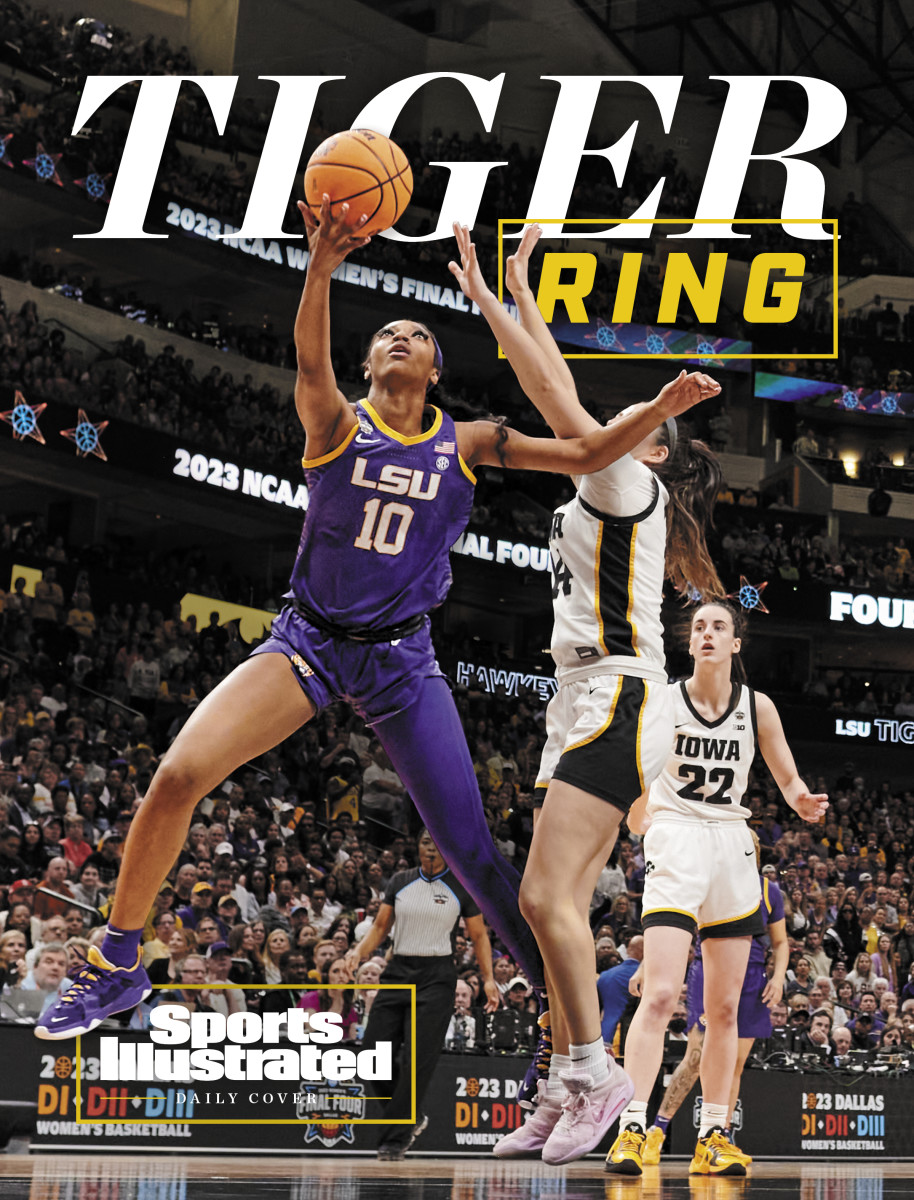

They shot 54% from the field and 11-of-17 from three in their best shooting performance since nonconference play in December. The result was a record for points in a championship game—LSU 102, Iowa 85—and a win. It yielded the first national title in the history of the program.

They had five players score in double digits. That included 21 for super-senior Alexis Morris, 20 for forward LaDazhia Williams, 15 for star Angel Reese, 10 for Johnson. And their leading scorer had been challenged by her coach the day before in practice. After a Final Four victory with zero bench points, Mulkey told her reserves all she wanted was for them not to hurt the team. So guard Jasmine Carson decided she would do everything she could to help. She came off the bench and scored 22.

Of the eight players who saw the court for LSU, just one was on the team last season, Morris, who finished her collegiate journey at her fourth school in six years. None of them were here two years ago. The same goes for their coach. Mulkey stunned the sport when she decided to leave Baylor after three national championships and return to her home state to build something new at LSU. She frequently spoke of high ambitions for her new program—including, yes, a national championship—but on modest timelines. They delivered (far) ahead of schedule.

It wasn’t straightforward. But they made it easier by learning when to challenge one another, when to lean on one another and, of course, when to laugh at one another.

“We’ve got a lot of big personalities on the team,” said Reese, clad in her championship hat, with her signature tiara beside her. “We go at it all the time. But at the end of the day, we love each other, and we’re sisters. We got to where we wanted.”

There is no playbook for integrating nine players into a team. That’s partially because adding nine players in an offseason was all but impossible until recent changes to transfer rules, and partially because it remains an undesirable challenge, even if now a technically feasible one. So the Tigers tried a few different ideas last summer. They set up a game of volleyball. They went to Topgolf. But they quickly realized this team would not find its identity in formally organized activities. Instead? They’d learn it on the court.

“In the summertime, we started playing pickup,” Reese said. “We were talking trash to each other and just getting each other better.”

Their pickup games were almost every day in the summer and Saturdays in the preseason. (“Those were some tough, tough Saturdays, banging and everyone just competing,” says Emily Ward, the only four-year player on this team and one of just two holdovers from the prior coaching regime.) Those chippy afternoons gave everyone a sense of the personalities around them. And it helped them bond more than any structured, team-sanctioned activity could.

“I felt it in my soul in the summer when we were playing pickup,” Johnson said. “Everybody was talking crazy to each other. That’s when I knew we’ve got some hoopers on the team.”

This laid the foundation for a team that finished the regular season with a record of 27–1. They had lost only to undefeated reigning national champion No. 1 South Carolina, in a tough game in February, and they looked forward to a rematch in the final of the SEC tournament.

They didn’t get there.

Instead, LSU blew a 17-point lead in the semifinals of the conference tournament to Tennessee. “It was embarrassing,” says Tigers director of player personnel Jennifer Roberts. That sent the team home for two weeks to think about what had gone wrong and whether it could fix it before the NCAA tournament.

Mulkey walked into the Tigers’ first practice back with copies of a poem called It’s Only One Possession. (A few lines: “A put back for two, quite simply due, to my failure to turn and block out / But it was only one possession, I didn’t commit a crime. … In post game I sit at my locker / Pondering what more I could do. I realize the value of each possession / What a shame that we lost by two.”) She had them read it together. And then they started watching film, possession by possession, breaking down how the game might have turned on each one.

At first, “everybody blamed each other,” says guard Kateri Poole. But the session was a message from Mulkey: You have to come together and take responsibility. And she was hardest on her best player. Reese had finished the game with her standard double double: 22 points, 11 boards, the team’s leading scorer and rebounder. But she’d faded hard in the fourth quarter when the game was on the line.

“She was hard on Angel; she was really hard on Angel in that film session,” Redus says. “And I think when you can be really hard on your best player ... it can make or break you.”

Reese was determined to show Mulkey it would be the former.

“I let my team down,” Reese said. “I felt like I needed to develop a little bit more and be able to play in those situations when it does come down to it.”

She used the two weeks to hit the gym. Assistant strength and conditioning coach Thomas Lené offered to take pictures of Reese before their first session: What if they worked so hard that she could see physical differences in before-and-after pictures? In addition to conditioning and weightlifting sessions with the whole team, she met the coach each day before practice, and the centerpiece of their work was an intense bike circuit. For 20 seconds, Reese would give everything she could on high resistance. For 10 seconds, she’d rest. She’d repeat this eight times. Then she’d do the whole thing again.

“You could just tell how much she wanted it,” Lené said.

Meanwhile, Mulkey brought up the poem in every practice. It was only one possession. The players thought about it in the weight room, they thought about it in film sessions, they thought about it in scrimmages. It was only one possession.

“We lived it,” LSU assistant director of basketball operations Chante’ Crutchfield said. “We went through it in that Tennessee game. We lived it, so the kids knew that everything on that piece of paper was real.”

At the time, LSU didn’t intend to make this a mantra for the rest of their season. (“You have to kind of be creative,” Mulkey said of finding ways to motivate her team. “Some of it’s corny to people.”) But it stuck. As the Tigers made their way through the tournament, winning game after game, they kept going back to sitting in that film room, listening to their coach pick apart their performance, holding that poem on that sheet of paper. Their tournament wins did not always look pretty. In several games, their offense ran cold, and they instead had to rely heavily on their rebounding and defense. But they returned to the same idea throughout: It’s only one possession. They didn’t want to regret it.

This season required almost the whole team to take something of a leap of faith. The coaching staff wasn’t sure how the roster would come together. The freshman recruits and earliest transfer commits did not know just who their future teammates might be. But they all knew they wanted to build something with Mulkey.

That was especially true for their biggest transfer.

Reese was initially considering storied programs South Carolina and Tennessee. She was undecided between the two but certain it would be one of them. (“LSU wasn’t even in the question,” she said.) But that changed with a call from fellow transfer Poole. Both were coming out of the Big Ten—Reese from Maryland and Poole from Ohio State—and they had known each other since they were young teenagers. Poole badly wanted to play with her. But she didn’t go for the hard sell at first. Instead, Poole simply asked Reese what she thought.

“She told me Kim was crazy,” Poole says with a laugh. “Crazy, but good.”

Poole responded: Sure. But isn’t that maybe what you need?

Reese decided to take the visit. She realized soon afterward she did not want to take any others.

“I fell completely in love and canceled all my other visits,” Reese said. “It was just God telling me the direction I needed, and I needed Kateri to tell me, This is where you need to be.”

Much of that direction, Reese says, came from Mulkey. The forward had success at Maryland: She was coming off a season when she averaged 17.7 points and 10.6 rebounds. But she wanted to be even better. She wanted to be a presence in games longer, to stay out of foul trouble, to improve her conditioning. She wanted to be challenged.

She felt she needed Mulkey. But her teammates freely admit that’s not the case for everyone.

“A lot of people can’t be coached by her,” Johnson said. “You’ve gotta be strong. You’ve gotta be willing to want to be great.”

Mulkey’s approach did not change during the tournament. The day before their second-round game against Michigan, she walked out of practice, frustrated with what she was seeing. (“It was rough,” Redus says.) The players responded the next day with their biggest margin of victory in the tournament. A similar dynamic came two weeks later. After their Final Four victory over Virginia Tech, Mulkey turned to her reserves with a directive wrapped in light scorn. Yes, they’d just made it to the national championship, but they’d done so in a game with zero points from their bench. She didn’t ask them for more. She just asked them not to hurt their chances.

“Kim challenged our bench after that last game, because they didn’t really do what they were called upon to do,” Roberts says. “She just told them, ‘We don’t have a lot of depth, so when your name is called, boy, you’ve got to be ready.’ … She just challenged them, When you come in, don’t hurt us.”

The bench responded. (With early foul trouble for starters in a closely—and contentiously—officiated game, they had to.) Last-Tear Poa delivered two three-pointers. Sa’Myah Smith played aggressive defense. And Carson, of course, scored 22 on 7-of-8 shooting including five from beyond the arc. “Every player dreams of being on a big stage like this and having the game of your life,” Carson said. “For it to come to fruition, it meant a lot.” And it started with a dare.

Mulkey tries to select for this when she recruits. She encourages potential new players to call those she has coached previously. If being pushed like this doesn’t motivate you? Don’t come play for her.

“A fresh start, that’s what I came to LSU for,” Reese said. “Just being able to be within a program with Kim Mulkey, where she was going to push me every day and keep me humble and get me to the next level, I think was important for me. And I needed Coach Mulkey. That’s just what I needed. I needed Coach Mulkey.”

So did LSU. She built her team unconventionally, working significantly ahead of schedule with players who responded best to being needled. They played the way they wanted to for a coach who told them they didn’t have to change. “I don’t fit in a box that y’all want me to be in. I’m too hood. I’m too ghetto. Y’all told me that all year,” Reese said. “This was for the girls that look like me, that’s going to speak up on what they believe in. It’s unapologetically you. That’s what I did it for tonight. It was bigger than me.” And they delivered a title.

“We’ve got a locker room full of kids who like tough love,” Mulkey said. “I don’t have a locker room of a bunch of passive ones, as you know. They will tell you how they feel. They’ll talk trash on the floor.”

She then gave them not another challenge but a sincere compliment.

“They just blessed me. They’re ballers.”

Watch college basketball games live with fuboTV. Start your free trial today!