Louisville's Denny Crum Was One of College Basketball's Great Innovators

When the popularity of men’s college basketball was exploding right after the Bird-vs.-Magic national championship game of 1979, Louisville was there to grab the baton and soar with it, above the rim, helping take the sport even higher. For a stretch of time in the heyday ’80s, the Cardinals were the coolest program in the country. They won big; they were exciting; they were colorful; and they had soul.

Coach Denny Crum was the leader, and he was a fearless one. Crum, who died Tuesday at the age of 86, continued the evolution of college basketball as a showcase of Black excellence beyond where Texas Western and others had taken it. He, along with Guy Lewis at Houston, put all-Black lineups on the floor that dazzled with their high-flying style of play—they were fundamentally sound and athletically explosive, an intoxicating combination.

From 1980 to ’86, Crum won two national championships and went to four Final Fours. He took Louisville to six total Final Fours in his 30 seasons at the school, turning down at least one chance to go back home to California and coach his alma mater, UCLA. He wound up being a perfect fit at an urban school in the mid-South, becoming the most beloved figure in the university’s athletic history.

Beyond the wins and the titles, Louisville had a panache that spoke to its coach’s looseness—which stood in stark relief to many in his profession who were rigidly in control. When Dean Smith was running the talent-inhibiting Four Corners at North Carolina, Crum’s Cards were throwing alley-oops. When Bob Knight was locking into a half-court mentality at Indiana, Crum’s Cards were pressing full-court. And in a dynamic that was most acutely noticeable in the state of Kentucky, when Joe B. Hall was leading a buttoned-down program in Lexington, Crum’s Cards were known as the Doctors of Dunk.

All those coaches won championships. One seemed to have more fun doing it than the others. And the red-velvet sport coats he wore on the sideline added a flourish.

Louisville’s 1978–79 team has been credited in some circles as the inventors of the high-five. (There is considerable dispute about where the enduring sporting celebration started.) Players were free to grow their Afros as large as they wanted—’70s big man Ricky Gallon had one of immense proportion. When the ’79–80 team was starting its march toward the national title in Indianapolis, backup guard David “Poncho” Wright became the hype man.

Wright, who signed autographs that read, “Never wrong, Poncho Wright,” publicly laid out big dreams before the season began. After a November scrimmage, he declared there was “Noooooo stoppin’! Tell ’em all that. Tell Joe Barry Carroll [the dominant Purdue center at the time]. Tell Herb Williams [the Ohio State center]. Tell ’em all. The ’Ville is going all the way.”

And thus the theme for that season was born: “The ’Ville is going to The ‘Nap.’” The Cardinals did indeed get to Indianapolis, defeating UCLA for the school’s first title. Ninety-nine percent of the coaches in the country would have stroked out over Wright’s preseason proclamation and muzzled him—but not Crum.

In multiple ways, Louisville could be seen as a forefather of the Fab Five. Less of a lightning rod than the Michigan quintet that came along in the 1990s, but no less an embodiment of Black excellence on the basketball court.

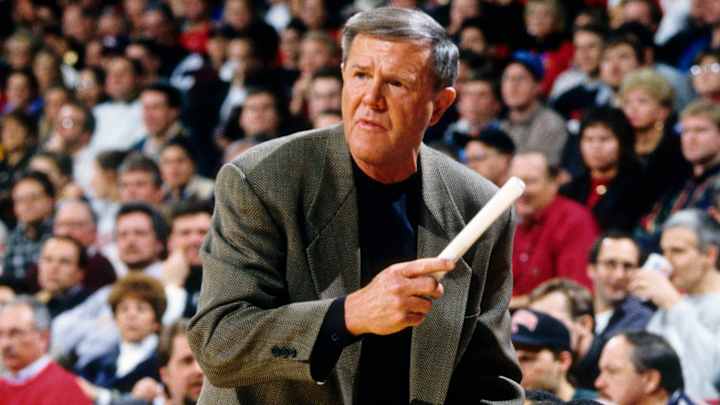

In addition to letting his players be who they were, Crum was a shrewd in-game tactician who never tightened up under pressure. (Hence the nickname “Cool Hand Luke.”) He had a sixth sense for what to draw up and when. With a rolled-up program in his hand—an homage to his former coach and boss, John Wooden—Crum looked like an orchestra conductor at work.

Louisville was also ahead of the recruiting curve. Crum and his staff found gems in the South that underperforming Southeastern Conference Schools overlooked, mined the northeast for megastars and kept many of the best players in Louisville home. There were title-winning players from Georgia (Derek Smith, Wiley Brown, Pervis Ellison) and Mississippi (Lancaster Gordon, Charles Jones, Kenny Payne). There were big stars from Camden, N.J. (Billy Thompson, Milt Wagner), and New York (Rodney and Scooter McCray). And arguably the biggest star of all from Louisville itself (Darrell Griffith).

For those six seasons from 1980 to ’86, Louisville was the best program in the country. Not Indiana, not Georgetown, not North Carolina, not Houston. Truth be told, the Cardinals were excellent for Crum’s first eight seasons as well. (He took over in ’71). But after the second national title in ’86, behind freshman “Never Nervous” Ellison, Crum’s tenure turned.

Assistant coaching turnover inhibited recruiting. Crum was a late adapter to the three-point shot, and his motor seemed to stop running as high. That 1986 Final Four was Crum’s last, followed by 15 seasons of diminished returns.

There was some scandal during that time as well, with multiple NCAA investigations that led to sanctions in the 1990s. I did some of the work on those while I was employed by The Courier-Journal, and it was a tense time—digging into a legend’s recruiting led to considerable blowback.

There was one Saturday morning when Crum called me at home, apoplectic about a story that I’d written in that day’s paper. He ended the conversation by shouting that he was going to buy the newspaper—the whole business—so he could fire me. That didn’t happen, of course, but relations were not good through the end of his tenure.

The thing with Crum, though, is that he wasn’t a grudge holder. It wasn’t in his nature to be an angry or bitter person. Years later we would chat amiably at golf outings or Kern’s Korner bar.

He was deeply hurt by his ouster in 2001, which was engineered by athletic director Tom Jurich to bring in Rick Pitino—a move that worked out extremely well for Louisville, for a long time. But, in that instance as well, Crum was not going to stay angry. In time, he was back around the program, shifting into the genial patriarchal role and graciously accepting the embrace of a fan base that loved him until his last day.

In an era when urban programs were having a power surge, Louisville became the best of them. And the Cardinals did it in the toughest neighborhood, rising up to become a legitimate rival to monolith Kentucky down the highway.

Without Crum birthing a heavyweight program, the annual series with the Wildcats—a high holy day on the state’s calendar every winter—would not have happened. The championships wouldn’t have happened. Even the move from iconic Freedom Hall to the gleaming, 22,000-seat KFC Yum! Center downtown, which occurred in 2010, wouldn’t have happened unless Louisville had become the most profitable basketball program in the country under Crum and sustained it under Pitino.

Denny Crum launched an era of Louisville dominance within a golden era of college basketball. And the way he did it was stylistically and socially significant. The sport was becoming progressively more cool, and for a time his Cardinals were the coolest of all.