Great Expectations: Oklahoma Unapologetically Lived Up to Its Dynasty

Oklahoma redshirt senior Alex Storako got the text from her pitching coach in the middle of the afternoon, a few hours before game time, with the biggest assignment of her life.

“Here you go,” Sooners pitching coach Jennifer Rocha had written. “Here’s your moment.”

It meant that Storako would get the start for a game that would either cement the winningest season in college softball history for No. 1 Oklahoma, solidifying a dynasty by giving the program a third consecutive national championship, or snap the longest winning streak the game had ever seen and push the season to the edge.

“I literally just kind of stared at my phone for a little bit,” Storako says. “My heart was just racing.”

It wasn’t surprising, except for all the ways it was. Storako has been one of the best pitchers in the country this year. She entered the championship series with a 1.12 ERA— eighth-best in Division I, which would make her the ace of just about every team other than her own, where she is behind not one but two other pitchers, Nicole May (0.91 ERA) and Jordy Bahl (0.92 ERA). It was Bahl who started the decisive championship series game last year and May who followed her in relief. But this stage would be new for Storako, who transferred this season from Michigan, partially because she was hoping for a moment just like this.

In other words, Storako would have been the obvious, automatic choice for a championship pitcher at any program other than Oklahoma, where the accumulation of talent made it a legitimate question.

Such is life for the Sooners. This is a team so deep and so skilled that it could reasonably make the call to start its No. 3 pitcher a few hours before game time at the Women’s College World Series. And this is a team so tested, so driven, so tough that it could make it work perfectly.

That’s not to say it would be easy. No. 3 Florida State was far too capable an opponent for that. On the strength of a dominant performance from Bahl, Oklahoma had taken Game 1 of this best-of-three championship series, 5–0. Yet both teams knew a greater challenge awaited in Game 2. Florida State’s ace, Kathryn Sandercock, would now be in the circle. The redshirt senior has an enviably tough arsenal—one of very few pitchers in the country able to truly match talent like that of Bahl, May and Storako—and Oklahoma had not seen her once in this WCWS. If Game 1 had not been particularly close, it was only because the real competitive stuff had been strategically left for Game 2.

But Oklahoma coach Patty Gasso had a strategy of her own. The Sooners would start with Storako, who matched up favorably with this lineup and had started against Florida State when these teams played in the regular season back in March. And if they got a lead, however slim, they would go straight to Bahl. As much as the Seminoles had just seen of her—Bahl had thrown a complete-game shutout in Game 1—the fiercely competitive sophomore was still the natural choice to close out a potential championship.

The game remained scoreless until the bottom of the fourth inning. While both teams put their share of traffic on the base paths, these starting pitchers managed to get out of every jam, albeit sometimes only with the help of their defense. (Sooners center fielder Jayda Coleman made a jaw-dropping, home-run-stopping catch to potentially save the game for Oklahoma in the third.) In the fourth, however, Storako gave up a solo home run to Florida State senior Mack Leonard. That might logically have seemed like an obstacle for the Sooners. Instead, it seemed only like a call to action. The plan had always been to give Storako a lead so they could switch over to Bahl. So they would do just that.

The Sooners’ seven, eight and nine hitters were up to start the next inning. And if they were not the most statistically likely players to build a lead, well, no one told them that. No. 7 hitter Cydney Sanders led off with a home run to tie it. No. 8 hitter Grace Lyons followed with a home run to go ahead. It was almost a little too slick, too convenient, to work as a statement on how this team functions: As soon as the Sooners were challenged, they leapt into action, executing their plan in the most direct fashion possible and showing off their depth in the process. They never looked back. Bahl entered the game for Storako in the bottom of the fifth, and, just in case, her teammates soon gave her an insurance run. But it wouldn’t make a difference—Bahl would not allow a single base runner in her three innings of work. She, too, would execute the plan as directly as she could.

Oklahoma 3, Florida State 1.

That left the Sooners with a final record of 61–1, the best in the history of college softball, on a win streak of 53 (and counting).

It is Gasso’s seventh championship at Oklahoma and her sixth in the last 10 seasons. It was also her roughest yet, she said. There were high expectations and scrutiny and hardships for past teams. But like this? It had never been like this. The Sooners had entered the season with a target on their back as defending champions. With transfers like Storako and Sanders, outsiders sniffed at them as an artificially built superteam, accusing them of taking shortcuts to bolster their roster. And when they began to win and win and win some more—garnering even more attention as those wins stopped looking like discrete victories and started looking like a historic streak—the pressure morphed into something more onerous. Gasso and Oklahoma did their best to shut out those external forces. But it was unlike anything they had done before.

“To be sitting up here and telling you this is still kind of amazing,” said Gasso, seated in front of a sea of reporters that would have been unimaginable for college softball just a few years ago. “Everybody’s out to get us. They want to bring down the Evil Empire—whatever it is. I don’t know.”

The veteran coach grinned, and then she shrugged.

“We just want to play ball,” she said. “That’s all.”

No one entered this season expecting Oklahoma to be better in 2023 than it was in ’22. That was not a statement on the quality of the roster so much as it was one on the laws of physics.

The 2022 Sooners had been one of the winningest teams in the history of Division I: Their 59–3 record finished behind only that of Arizona in 1994 (64–3) and UCLA in ’92 (54–2). The Sooners, like both of those teams, had romped to a national championship. Their offense had led the country in scoring, while their pitching had led the country in limiting scoring. They had looked nigh unbeatable. A program could perhaps hope to match that kind of performance. It could not really hope to exceed it.

Yes, one could reasonably believe this team was going to win another championship. Oklahoma was returning much of its core and making some of those aforementioned key additions through the transfer portal. But they had lost talent, too, most notably NCAA home run queen Jocelyn Alo, a two-time National Player of the Year. And regardless of who they had added or subtracted, when the starting point was 59–3, how could one believe this team could possibly get even better, just as a matter of simple mathematics?

“Honestly, I didn’t,” says Rocha, the pitching coach. “But this group of girls—just the fight and the will that they have is amazing. And they’ve just shown it all year long and put it on repeat.”

It took some time for that to manifest. The roster had a total of eight additions—both freshmen and transfers—and they did not jell right away. In one of their first practices, Gasso clashed badly with the team. “They didn’t like something that I was doing,” she said. “I didn’t like their response.” She has always been a demanding coach; that is part of why players choose Oklahoma, because they believe she can make them better, and because they know the work is worth it. But this felt like something different. Gasso realized that she did not have to ask more of the players in that moment. She had to ask more of herself.

“If I look like my clothes are fitting a little bit tight, it’s because I took each one of them out to breakfast or lunch or dinner, each one of ’em, and sat with them and talked to them,” Gasso said of that stretch in the fall. “Actually—I didn’t talk. I wanted them to talk. I needed to listen. … I surrendered my ego to make sure I did that. I think that was a step maybe in the right direction. Then things just started to flow.”

It wasn’t only Gasso who had to humble herself to make it through that early rough patch. Many of the players did, too. If others saw them as an easy, automatic superteam, they were learning that coming together on the field would actually require plenty of work.

“A big thing I had to learn was coming in, you can’t expect anything,” said third baseman Alyssa Brito, who transferred last year from Oregon and helped to guide many of the new players this year. “This is such a unique program in the way that we have so much talent. There’s a reason why you come here, and it’s because people just elevate you, not just as a player, but as a person.”

Gasso saw no better way to sharpen all this talent than to split the roster up and have them play against each other. They called these fall ball scrimmages their “Battle Series,” and fan interest was so high that Oklahoma not only sold out its ballpark for these games, it streamed them on ESPN+. It felt like a success all the way around. For the first time, they had a sense of just how good they could truly be. But when the season finally started in February, they realized they had been playing against each other so much that the experience of playing as one team was completely, totally foreign. “I guess we should have practiced all being in one dugout, and what it felt like,” Gasso said. They won all five games at that first weekend invitational tournament. But they weren’t yet playing like a cohesive unit.

The following weekend, they lost to unranked Baylor, 4–3, in what would become their only loss of the year.

“We had some hard conversations,” Sooners catcher Kinzie Hansen says of the aftermath of that game. “Truthfully, it felt like it was us against the world. … Everybody was coming at us. But after that, we were able to kind of shut all the noise off and just focus in.”

The Sooners talked about coming together to play how they wanted to play—to cultivate their own style, understanding that if some people would hate it, well, they could just go ahead. That ended up manifesting in all sorts of ways. But it was clearest in how this roster learned to draw walks. The Sooners hitters can make any plate appearance feel like a grand drama; they control the pace, stepping out of the box at will, asserting their power in this situation. (They have a D-I-leading .458 team OBP.) Even against the best pitchers, in the biggest situations, Oklahoma’s composure at the plate is so unreal as to be almost unsettling. And if they see a ball four?

“Literally, you’ll see our girls get walks, and they’re screaming,” says fifth-year senior Grace Green.

When the Sooners draw a walk, they yell. They spike their bats. They turn to the dugout, feeding off the energy of their teammates, and they motion to the fans, calling for even more. They love walks. Each one is just as good as a hit for them—maybe better.

This has been met with several lines of criticism. It’s unbecoming, people say. It’s too aggressive. It’s ridiculous for the best team in the country, the heavy favorite in every game it plays, to be so demonstrative for something like a routine walk. It’s tacky. It’s inappropriate for players who should act like they’ve been there before.

But the Sooners see it differently. “We never mean it disrespectfully,” says Lyons, the veteran shortstop and one of the team captains. “It’s all for our own joy and passion, never to tear down anyone else.” They know just how good they are, and how hard they have worked, and each walk feels like a reflection of that. Why not celebrate it?

Their coach has emphasized this point.

“You must be unapologetic about the energy and the celebrations you have,” Gasso said. “Because women have worked so hard to get here, yet still get judged for these things. That’s the way we play. … You either like it or you don’t. But we’re not going to apologize.”

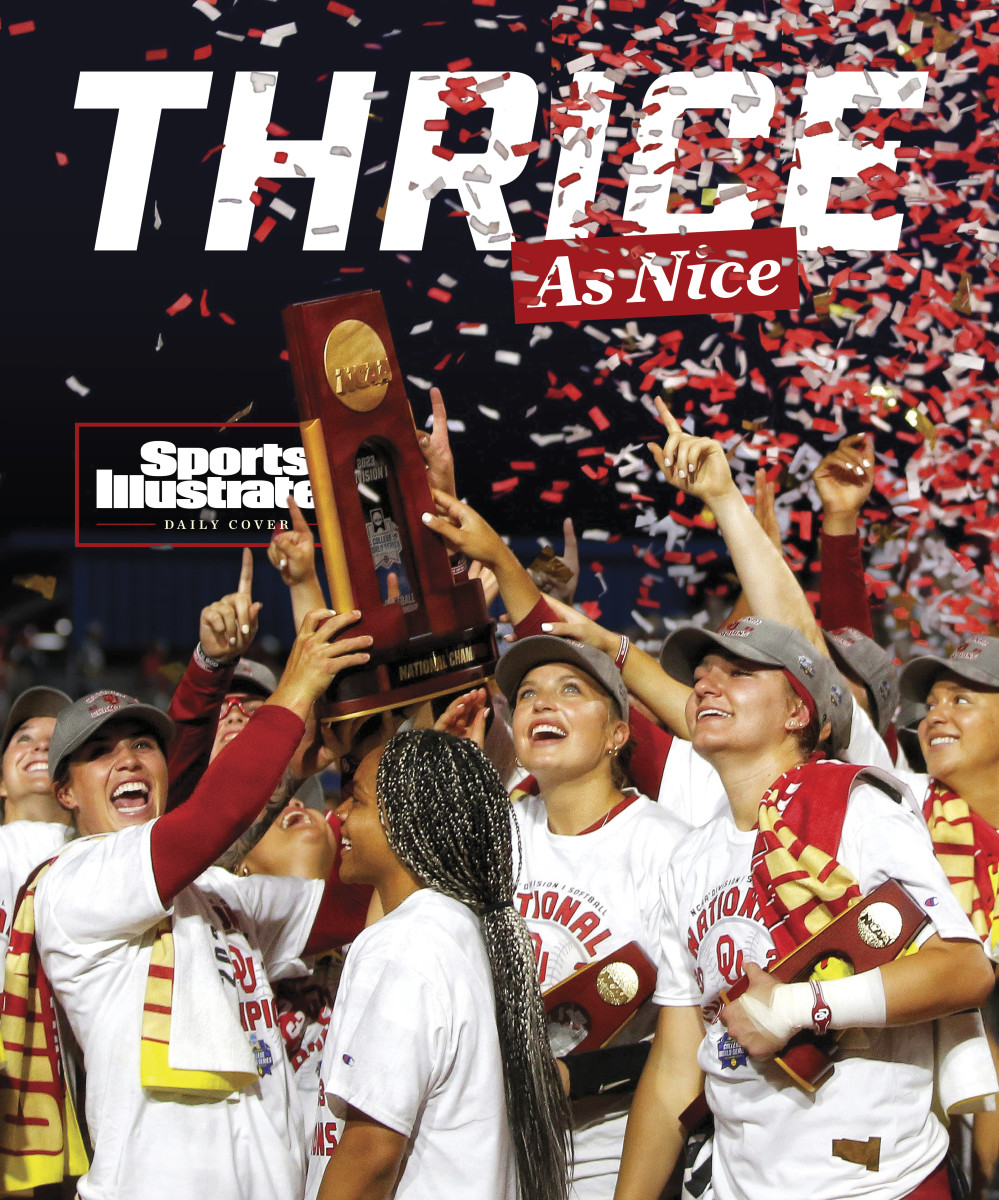

Oklahoma never has. The team celebrated every walk in the WCWS like this. And it celebrated its eventual title like this, too.

It can be difficult to adequately describe this sort of dominance. The Sooners’ numbers are only a starting point. There is the record win streak (53 games and counting). There is the fact that they are the first team to lead the nation in batting average (.367), fielding percentage (.988) and ERA (0.96). There are the four no-hitters and the dozens of shutouts and the hundreds of runs by which they collectively outscored their opponents. But there is something beyond the statistics, too.

There is the feeling that it never seemed as if they might lose.

This feeling held even when it was completely illogical. (Which, for all this dominance, still happened: Oklahoma had several close victories to go with all its overpowering shutouts. “There were a lot of people like, Oh, gosh, I wish you had another loss so you could learn from it,” Gasso said. “What do you want? Everyone go up there and just stand there, not swing the bat? We can learn from close wins. We can learn from anything we do.”) But the Sooners always made victory feel inevitable. They were simply too strong, too talented, with too many ways for them to win for it to ever feel otherwise. Even when they entered the final inning trailing by two against Oklahoma State at the end of the regular season. (They won, 4–2, with a series of clutch hits from the bottom of the order.) Even when they were locked in a scoreless pitching duel late against Stanford in their first game of the WCWS. (They won, 2–0, thanks to savvy baserunning with two outs.) Even when they were trailing in this decisive championship series game.

And the dynamic was clearest of all in the game that punched their ticket to the WCWS—an extra-innings victory over Clemson.

The Sooners entered the seventh inning down by three, having blown an early lead, with National Player of the Year Valerie Cagle on the mound for the Tigers. They got a pair of base runners. But there were soon two outs; next, two strikes; they were then down to what could have been their last swing.

“All of us thought we were going to win,” Green says. “I promise you. There was no doubt in anyone’s mind that we were going to win that game.”

It’s easy to say there was no doubt after the fact. But it seemed clear there was no doubt even in the moment. It was obvious in their approach: Hansen was at the plate. She’d swung through the first strike. She’d stood and watched the second, hugging the bottom of the zone, clearly not her pitch. And then, on 0–2, she swung from her heels.

It was, of course, a game-tying, streak-saving home run. It felt inevitable.

A win followed in extras. There hasn’t been a loss since.