Maryland Is a Fitting Home for the Power 5’s Most Groundbreaking Leadership Structure

There’s a poster on the bookshelf in Maryland president Dr. Darryll Pines’s office. Two words superimposed over a picture of Pines, football coach Mike Locksley and athletic director Damon Evans make its message clear: Representation matters. It’s an easy thing to say for those in college athletics as people become broadly aware of the need for diversity, equity and inclusion in hiring practices, especially in leadership positions. But it’s an entirely different undertaking to embody that ethos and do the actual heavy lifting of diversifying the workplace.

“Representation” can be reduced to buzzword status as many leadership roles in the college sports industry remain lily-white. But it’s clear that at least at the top of the leadership pyramid and the most front-facing sport on campus, the Terps are living it.

Not only are Pines, Evans, and Locksley each Black, but the main three assistants on Locksley’s coaching staff are, too (offensive coordinator Josh Gattis, defensive coordinator Brian Williams and head strength coach Ryan Davis). They were the first and only Power 5 school to achieve that distinction. Research conducted by ESPN in 2019 found that over half of P5 programs have never hired a Black head coach, and nearly 70% hadn’t hired a Black athletic director. (36% haven’t hired either.)

That this is happening specifically where it is should not be lost on anyone. College Park, Md. is in Prince George’s County, which borders Washington D.C. to the east, and it was for a long time regarded as the richest majority Black county in the entire nation, though that status has been challenged recently by Charles County to the south. PG County is still a staple of what a Black upper-middle class community can truly be. And perhaps nobody connected to Maryland athletics embodies this part of the world like Locksley, who grew up in D.C. as a Terps fan and had multiple stints as an assistant before finally getting his dream job permanently in 2019. He is unapologetically Black, from the paintings of Tony Dungy, Eddie Robinson Sr. and Doug Williams waiting to be hung on the walls to the letters of his Omega Psi Phi Fraternity on the shelf.

“I don't even know what code-switching means. Seriously, and I always say this, and I mean this in all honesty. Growing up in this area probably was the best thing that ever happened to me,” Locksley says. “Whatever you see from me is who I am. And in this area, you didn't have to apologize for being a successful Black person. I don't know if you can always do this everywhere. So, I am who I am. I don't think I have to change because I think who I am is I'm able to relate or find common ground amongst everybody. That's one of the things I think sports allows you to do.”

This is his third stint on a Terps staff. He first coached under Ron Vanderlinden and Ralph Friedgen from 1997–2002 before going to Florida and then Illinois with Ron Zook. Locksley became the Illinois offensive coordinator in 2005 and was a key cog in recruiting players from the D.C. area to Illinois; He still has an article commemorating the fact that there were 18 players on Illinois’s 2008 Rose Bowl team who were from the broader D.C. and Baltimore areas (known as the DMV), including Arrelious Benn and Vontae Davis, the latter of whom Locksley got to come to Champaign by promising his grandmother he’d take him to church every Sunday. He got his first head coaching job at New Mexico and weathered storms both on and off the field, including a 2–26 record, an altercation with an assistant and a discrimination complaint from an administrative assistant (that was later resolved and withdrawn). Locksley was fired after starting his third season 0–4, and in embarrassment, didn’t leave his house for days. He finally got off the mat after a pep talk from mentor and former Maryland AD Debbie Yow, who told him “failure isn’t final.” Locksley went about taking that advice and rebranding himself.

“It blew me up a little bit. And I just thought, if you look at history, Black coaches get one opportunity to do what I did at New Mexico,” Locksley says. “I didn't think I would see another opportunity to be head coach again. At that time, my agent at the time was Trace Armstrong. And I can remember Trace saying, ‘Look, go get a journal. And I want you to write in the journal what worked and what didn't work. And if you ever got another chance what you would do differently. While it's fresh in your mind, quality control it.’”

Locksley ended up back close to home, as offensive coordinator for Randy Edsall in his second spin as a Maryland assistant. When Edsall was fired, Locksley ended up in the job he’d always wanted, Maryland head coach, but only on an interim basis. Initially he turned it down, feeling as though he couldn’t have any more losses on his résumé if he ever was going to get the job for real. Locksley was convinced to take it because of the players, and he felt it was the right thing to do. But he didn’t get the job permanently after a 1–6 run. New coach D.J. Durkin offered him a chance to stay on staff, but as a position coach rather than a coordinator, which he’d been since 2005 other than his time at New Mexico.

“If I ever wanted to be the head coach at Maryland, I couldn't be a part of another coach that got let go. I was part of Randy's staff. Being on D.J.'s staff, if it didn't work, I'd be done. I always wanted to be the head coach at Maryland. And so I go to Alabama, take a step back to move forward.”

In retrospect, Locksley calls not getting that job a blessing, because of where it led him. He stuck on Durkin’s staff for a couple of weeks before heading to Alabama for an off-field analyst role at Yow’s suggestion. He had opportunities to be a coordinator elsewhere, but a chance to observe Nick Saban’s organization from the inside was too much to pass up, and a contractual quirk in his Maryland deal made it easier to take the step back in compensation when Durkin hired someone else to call plays.

Everything with Locksley goes back to his relationships. He kept tabs on the Terps from afar while coaching at Alabama, and when Maryland offensive lineman Jordan McNair died after collapsing during a summer workout in 2018, Locksley found himself deeply affected. Not only did a player pass away at a place that meant so much to him, but he had recruited McNair while he was in high school at McDonogh, just outside of Baltimore. Locksley’s son, Kai, played AAU basketball with McNair, and the day McNair signed with Maryland, Locksley’s daughter Kori signed to play soccer at Auburn after a standout career of her own at McDonogh. But there was another deeper connection, as one of Locksley’s sons, Meiko, had been killed the year before.

“I called [Jordan’s father] Marty,” Locksley says. “And I said, ‘listen man, I just went through what you're going through. It's tough, but I want to be here for you. I can tell you how you're going to feel. I can tell you what you're going to have to do. I can tell you how at the funeral, you're going to feel like you're having a third-party out-of-body experience, watching people come in and you're going to have to be the rock. And when it's done and that casket closes and you get home, I can tell you the pain you're going to have where you won't be able to get out of bed for two, three days.’ And I talked him through every step of the way from him being in the hospital to him passing. I'm coaching at Alabama now. I'm not even at Maryland. But because of the relationship and having gone through what I went through, it was paying it forward. Here's a dad that's going to have to deal with being without him. Let alone, that's their only child.”

There are hourglasses all over Locksley’s office, a reminder that time is the most valuable commodity we have in this life. In 2019 after Durkin was fired and Maryland was looking for a new head coach, Marty McNair called him to see if he wanted to put a word in for him. At the time, the McNair family was still fighting a lawsuit against the university, and the community was deeply fractured as then-president Wallace Loh retired in the wake of the scandal (eventually being replaced by Pines). It was everything he’d worked toward, but he had to make sure one thing was in order.

"I won't take this job if I know I don't have the support of you and [McNair’s mother] Tonya, because I can't sit on people's couches and recruit their kids in Maryland when they're going to ask questions about the safety of their child, and is it a safe place? The only way I can circumvent that is by knowing that I can say, ‘Ask Marty and Tonya if it's safe enough now,’ because of the work they'd done to ensure that what happened to Jordan never happens again.”

Relationships aren’t just how Locksley got the job in the first place. It’s how he operates within it as well. It’s why former Alabama stars Jaylen Waddle, DeVonta Smith and Jerry Jeudy recently came to town to spend a weekend, and Jalen Hurts hosted a crawfish boil in the D.C. area this spring. Shortly before sitting down with Sports Illustrated, Locksley was touring a Maryland donor through the facility, doing relationship maintenance with someone who has deep pockets to help the Terps compete in the new NIL world.

As the sport becomes more transactional, there’s an anxiety that tampering from other schools can affect even the most firmly built coach and player/family relationship dynamic. Locksley has tried to be creative to combat that, for instance, developing what he calls “sustainable relationships,” unique ways to add value to an athlete’s time at Maryland. It stems from a recruiting miss while at Alabama. Locksley had been recruiting offensive lineman Nicholas Petit-Frere hard, and it was crunch time before signing day. The Tide were battling Ohio State to sign him, and Locksley met with the player and his mother, Loris, along with Saban so the legendary coach could seal the deal with his final pitch centering on championships and NFL potential. Petit-Frere’s mother stopped Saban mid-stream, and took the conversation in a different direction. As Locksley recalls, she asked Saban about what happened to the players who didn’t make it to the NFL, and uncharacteristically, Saban was a tad thrown off.

“Not because there aren't guys that haven't graduated from Alabama that are doing great things. But for whatever reason, it didn't come out fast enough,” Locksley says. “And it was like that 10-second pause felt like 10 minutes to me because I'm thinking, Alright. Come on now. Come on, Coach. Let's go. And then, he eventually got into some things of what some of the successful kids are doing in the program. But we lost Nick to Ohio State. And Ohio State had put together a presentation of former players, what they're doing, doctors, lawyers, all this stuff. And I thought that was pretty neat. But ours wasn't maybe as organized as theirs was. So, I just remember thinking, when I get to Maryland, if I ever get the chance to be a head coach again, I'm going to have a plan for that to be able to answer that question."

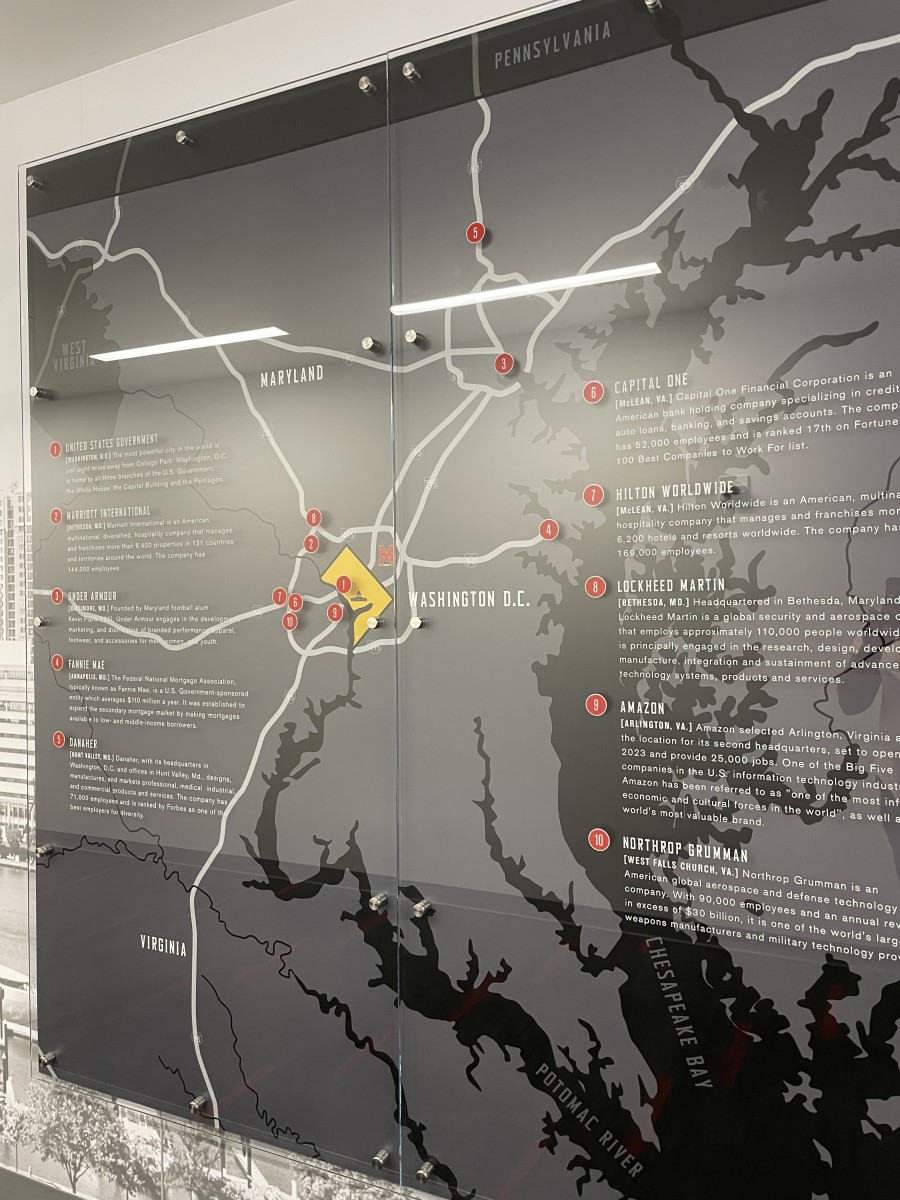

Locksley initially launched a mentorship program to take advantage of Maryland’s location between two large metro areas, with numerous major corporations headquartered and based within driving distance. A large map of the area hangs in the football offices. He points to the program’s early success with former linebacker Nnamdi Egbuaba, who was paired with the co-founder of a snack vendor for an internship. That led to a mentorship relationship, which got Egbuaba (who is from Nigeria and was in the country on a student visa at the time) connected with an immigration attorney who helped him earn citizenship. Egbuaba is currently in sales for PepsiCo.

It’s lessons like that, which Locksley picked up in Tuscaloosa, that he’s using in his second chance in charge. But he’s not the only person in Maryland’s athletic department who’s getting a second shot after a very public failure. His boss, Evans, was the athletic director at Georgia before being arrested, charged with DUI and resigning in 2010.

“When you have past transgressions like I have, they're going to always use those against you,” Evans says. “You've got to understand that and you have to accept that. What I always tell people is what I went through at Georgia, I would never wish on anybody. It was extremely, extremely hard but, again, no one to blame but me.”

Evans returned to college athletics as Maryland’s athletics CFO in 2014 before a messy rift with then-athletic director Kevin Anderson, that ended with Anderson being ousted and Evans being named interim AD in 2017, then permanent AD after a search chaired by Pines (who was not yet president of the school) in mid-2018. All of the instability led to the athletic department being described as in “chaos” by an external investigation into the football program’s culture following McNair’s death later in 2018. It was in that dysfunction that Evans took over and had to go about rebuilding trust within a deeply fractured athletic department.

“Trust is two components: character and competence,” Evans says. “First, you've got to be competent enough to do the job. I needed to show people that I had a level of competence to do the job. The character was a challenge for me because people are going to put you in a box when you've done something wrong. ‘He's this.’ As I've learned, you can regain trust. It's extremely hard to regain trust, but it takes time and it comes by your actions.”

Evans is preaching patience with his two biggest hires, men’s basketball coach Kevin Willard, who did make the NCAA tournament in his first year, and Locksley, who has stabilized the program with back-to-back bowl berths.

You may wonder what the real value of this throughline of Black leadership at key positions is. It may be difficult to quantify in a sport where wins and losses override all else, but that it is happening allows for the multiple dynamics of being Black in athletic administration and coaching to come to the forefront at a Big Ten school. Consider the push and pull between being regarded as a recruiter and an Xs-and-Os coach, which is a fraught one among Black coaches.

“I look at Locks's path and having had the opportunity to hire Locks and before that to get to know Locks because I was here while he was working [as an assistant], you've got to take a look at an individual in totality. And that's what I did with Locks when I sat down to make a decision about a football coach,” Evans says. “When you get to this level, the candidates you identify, all of them can coach. Some are better coaches, some are better recruiters, some are better organizers, but Locks had all those tools. I got tired of people talking about, ‘Locks is a great recruiter,’ and they didn't want to focus on the Xs and Os. He did a pretty good job at Alabama as the coordinator there.”

It can become a scarlet letter to only be seen as a recruiter, despite the fact that the ability to acquire talent is the most direct route to competing for a national championship in a sport without a salary cap or forced parity. But when a coach is slapped with the tag because of his ability to appeal to teenagers, it can cut the wrong way. Gattis spent a year with Locksley as co-coordinator at Alabama. Gattis, a rising star in the coaching ranks who has interviewed for multiple head coaching positions, held the title of offensive recruiting coordinator at Vanderbilt and Penn State.

“I hated that title, and I held it for about six years and was very successful in the role that I served because of the fear that I would only be labeled as a recruiter,” Gattis says. “At that time, my greatest strength was in development of position players that I was coaching. I felt like my work as a position coach was getting overlooked by the recruiting label. At that time, I had asked for that title to be taken away, and I really started taking a different approach to recruiting. There's social media, there's 247, there's Rivals, there's a lot of guys across the country that want their name to be involved with recruits or asserting recruiting mentions. I've always been a guy over the last few years that I've tried to keep my name behind the curtains, because I want to be known for what I can do offensively as a coordinator.”

Gattis left Tuscaloosa and earned duties as sole play-caller at Michigan and then Miami. A key boost to the résumé of any young coach, but especially a young Black coach—and doubly so for an offensive coach who did not play on offense during his career, much less play quarterback (a fast track to becoming a head coach for many white coaches). Gattis says there were times he regretted coaching on the offensive side of the ball, because the road to get to the coordinator job seemed so difficult.

There’s also a coach like former Texas A&M and Arizona head man Kevin Sumlin, who is Maryland’s co-offensive coordinator, assistant head coach and tight ends coach. It’s just flat out cool to have him in the room.

“I sit next to Sumlin in the staff meeting and just a few years ago, I was at Gody High School watching his Texas A&M teams and Johnny Manziel play,” defensive coordinator Brian Williams says. “Now, I'm sitting next to him at University of Maryland. So it's definitely something that I'm always inspired to be a part of and the uniqueness of this even makes it even more special.”

They all know the deal. This is college sports, and you don’t get to have these jobs in perpetuity if you don’t produce, no matter how much everyone’s in lockstep about diversity’s importance. Some schools have presidents who keep athletics at an arm's length. Pines is not that kind of president. He chaired the search for the Big Ten’s new commissioner, and he gives a speech to the athletic department at the start of every school year, where he tells the coaches assembled he expects a championship in every sport. And he says he’s serious about it.

“I believe that diverse thinking, and not just racial, ethnic wise—geography, gender, religion, all kinds of backgrounds, when you bring them together, you get the best product,” Pines says. “I say that from several years of experience of doing this. So, I'm an engineer, we build teams all the time, we build very diverse teams. And we build very diverse teams because we've got complex problems that we have to solve. And it needs input from somebody from ... I don't know, Lithuania. Or it needs somebody from Ghana. Because they see things totally different than how I would've seen it.”

Is football as complex or as important as engineering infrastructure projects? No, but its impact on a university community cannot be overstated when success occurs. In a sense the stakes are heightened for a group of Black coaches and decision makers, because of what happens if they don’t succeed.

“A lot of Black head coaches may or may not admit it,” Sumlin says. “But it's not just you're coaching your team, you're also wanting to create a situation where other people that look like you can have those opportunities. And the way to do that is to have some success in your own role. Your success or lack thereof can create opportunities or sometimes non-opportunities for people that look like you.”

It’s fitting that one of the other paintings in Locksley’s office is of Dungy, who had success under Dennis Green in Minnesota, parlayed it into a head coaching role, and paid it forward by having Lovie Smith, Herm Edwards and Mike Tomlin on his Buccaneers staffs. Locksley has taken his advocacy a step further, founding the National Coalition of Minority Football Coaches, with the stated goal to prepare, promote and produce more minority coaches.

Some of the way Maryland’s hierarchy looks is by happenstance, some of it is by design. But all of it is a beacon for diversity in a major athletic program. Because above all else, representation matters.