Inside Michigan and Ohio State’s Rule Book War

For the last few years, Michigan and Ohio State have been engaged in a game within The Game, using the rule book as a weapon. Self-interested parties masquerade as virtuous ones. Right and wrong are not just character judgments; they are game pieces.

Michigan’s illegal signal-stealing scheme and the ensuing hysteria are another stage of an ongoing battle. Rules are supposed to be guardrails to protect the integrity of competition and the well-being of participants, but in many ways, major-college football is now a professional sport with an amateur rule book. This has created an unfortunate dynamic: Coaches can operate within the rules but outside the spirit of competition. They can operate outside the rules but within the spirit of competition. And they can weaponize the rules to use against one another.

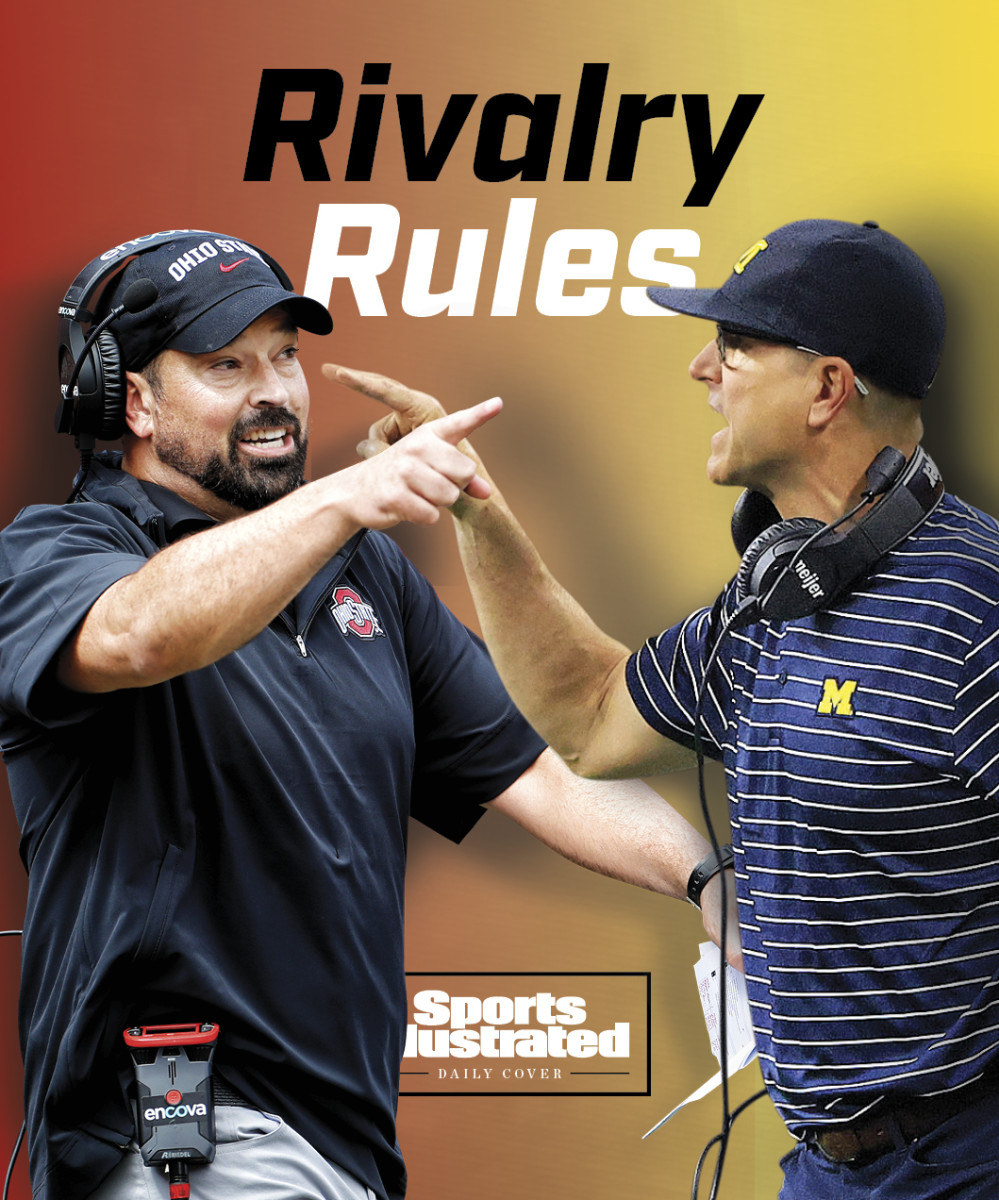

Michigan’s Jim Harbaugh remains suspended by the Big Ten for this weekend’s battle against fellow unbeaten Ohio State. There is still no public evidence that Harbaugh knew anything about the signal-stealing scheme, but he has been an active participant in the game within The Game, selectively using both the rules and his position to present himself as ethically superior to his rival. Now others are doing the same.

Outrage—real or exaggerated—is part of the game. When the sign-stealing story broke, Big Ten coaches and athletic directors urged commissioner Tony Petitti to act and shared their feelings anonymously with media outlets. (Sports Illustrated asked an Ohio State representative whether Buckeyes coach Ryan Day was one of the coaches who pushed Petitti to punish Harbaugh; the representative said Day would not answer questions for this story.) Michigan countered by revealing that Ohio State and Rutgers had given Purdue a sheet full of Michigan’s signals before the Boilermakers played the Wolverines in the 2022 Big Ten championship game—essentially giving Purdue the same advantage that former Michigan staffer Connor Stalions allegedly gave his team.

Harbaugh called it “collusion.” But where is the line between collusion and standard practice? Before Michigan played Ohio State in 2018, Harbaugh and several assistant coaches held a conference call with Purdue coach Jeff Brohm and his assistants to share strategies with each other, sources on both sides of the call say. Purdue had beaten Ohio State, 49–20, earlier that season. Michigan had just beaten Purdue’s upcoming opponent, Indiana. (Brohm, now the coach at Louisville, declined comment. Michigan declined to answer any questions for this story, citing “open matters with the NCAA.”)

In both of these instances involving the Wolverines, the “collusion” failed; Ohio State throttled Michigan in 2018, and Michigan blew out Purdue in December 2022. (Purdue did beat Indiana, though!)

The Big Ten says it was not trying to placate angry constituents when it suspended Harbaugh for three games, a punishment he has now officially accepted. But how do you separate the crime from the uproar around it?

In September, after the Buckeyes came back to beat Notre Dame in an epic thriller, Day told a national television audience, “This is a tough team right here. We’re proud to be from Ohio. It’s always been Ohio against the world.”

No. It’s always been Ohio against Michigan.

Harbaugh and Day have been building toward this moment for years.

Follow along.

When Harbaugh coached the San Francisco 49ers, he got so excited after a win that he gave Lions coach Jim Schwartz a drive-by handshake. Schwartz got mad and chased after him. Harbaugh said he would do a better job with the postgame handshake and reverted to his usual NFL self: tight-lipped publicly, feisty internally, focused on the game on the field.

But as a college coach, Harbaugh has gone out of his way to spar with other coaches. At Stanford he told reporters he heard USC’s Pete Carroll might leave for the NFL, and late in a blowout win of Carroll’s Trojans he went for two. At Michigan, he has feuded with Hugh Freeze (“You’ve got a guy sitting in a big house, making $5 million a year, saying he does not want to sacrifice his time”); Mark Dantonio (“Congrats on turning around a 3-9 team, plagued with off field issues”); Luke Fickell; James Franklin; and of course Day.

This has pissed off other coaches for a lot of reasons—one of which is that among Power Five football teams, pretty much nobody follows all the rules to the letter.

The most obvious example of this is the use of “analysts.” The NCAA limits programs to 10 assistant coaches. The rule is a relic from the days when schools actually tried to control costs. It no longer makes sense for Power 5 schools paying a fortune to head coaches, but it is still the rule.

Coaches at power programs found a workaround: hire experienced coaches as “analysts,” meaning they can watch film and shape strategy but aren’t allowed to coach during practice or teach skill development. How this serves “student-athletes” is a mystery. The rule is so relentlessly broken on a daily basis around the country that many players don’t even know that analysts aren’t allowed to coach.

By 2020, Harbaugh had a full-blown Ohio State problem. He was 0–5 against the Buckeyes, and Day had just poached defensive assistant Al Washington from his staff.

That spring, a photo surfaced of Washington apparently coaching Buckeyes players during a time when it was not allowed. Harbaugh upbraided Day on a Big Ten coaches’ conference call. That led to Day’s infamous comment to his team that they would “hang 100” on Michigan, which led to Harbaugh’s later comment, “Sometimes people are standing on third base, think they hit a triple, but they didn't.”

Michigan also turned Ohio State into the NCAA, a person who was aware of Michigan’s actions at the time told SI. Ohio State ultimately acknowledged a Level III (isolated or limited) violation and paid an appropriately minimal penalty. But the game had just begun.

On June 23, 2021, a high school placekicker from Hartland, Mich., named Nathan Dibert used Twitter to publicly thank Michigan coaches Bradford Banta and J.B. Brown for working him out in Ann Arbor.

But Banta and Brown weren’t coaches. They were analysts. They were not allowed to work Dibert out.

Multiple other schools turned Michigan in for the apparent rule violation, a person familiar with the ensuing investigation told SI.

To sum up: Budgets are now so enormous that programs can afford to assign staffers to scour social media for evidence that another school broke a rule that was designed to curb expenses.

Welcome to the modern era of college football.

Michigan never even offered Dibert a scholarship. He signed with LSU. But before he did, he inadvertently provided the end of the ball of yarn that the NCAA would start to unspool. NCAA investigators and Michigan compliance officers needed to figure out how frequently the team had violated this particular rule. That meant going back and figuring out which recruits had visited the program and what had happened on their visits.

During the course of that probe, a person with knowledge of it told SI, investigators learned that at least two recruits who took official visits had also taken unofficial visits during a time when the NCAA prohibited any in-person contact between coaches and recruits due to COVID-19. From March 2020 until the end of May ’21, recruits were allowed to take self-guided campus tours but were not allowed to meet with coaches or enter athletic department buildings.

The recruits have not been named publicly. But a person familiar with the infractions tells SI that one recruit was cornerback Myles Pollard of Brentwood, Tenn. Pollard gave a video interview in March 2021 to 247Sports about his unofficial visit: “It’s pretty nice in Ann Arbor … facilities” He paused. Then he said: “I didn’t really … I looked outside. … It was nice.” He smiled. “I wish I could go inside, but we can’t.”

Pollard later signed with Michigan and explained why in a first-person story for The Tennessean: “The first time I walked on campus, it felt good. … I was relaxed. I was comfortable. Then I got a chance to tour the football facilities and meet the coaches and players. …

“By the time I went back for my official visit, I could tell the team was believing in the changes the new coaches were making.”

Pollard’s official visit occurred 11 days after the no-contact period ended. Michigan also declined to answer a question on Pollard’s situation.

Sources tell SI that Harbaugh met with another recruit, offensive lineman George Fitzpatrick, of Englewood, Colo., during the COVID-19 no-contact period. Fitzpatrick ended up at Ohio State. Fitzpatrick’s father, Mark, declined to comment to SI on his son’s behalf.

The COVID-19 visits were not the only violations. In 2021, Michigan defensive lineman Taylor Upshaw gushed to the media about his on-field work with assistant coach Ryan Osborn. But Osborn, like Banta and Brown, was an analyst. The Detroit Free Press pointed out the rules violation that August.

During the investigation into the COVID-19 violations, the NCAA concluded Harbaugh was not fully truthful. Media outlets favorable to Michigan convinced fans the whole case was about buying a recruit a cheeseburger. The school tried to negotiate a resolution that would include a suspension for Harbaugh, but those talks broke down. NCAA vice president of hearing operations Derrick Crawford got so frustrated with backlash from Michigan fans that he issued a rare public statement declaring the investigation was about impermissible contact and coaching violations during a pandemic, “not a cheeseburger.”

Michigan self-imposed a three-game suspension for Harbaugh, which he served in September. It also self-imposed a one-game suspension for co–offensive coordinator Sherrone Moore, who was recruiting Fitzpatrick.

The NCAA still hasn’t finished that investigation or the one into sign-stealing. What might happen next is difficult to project. By next week, Harbaugh will have already served six games worth of suspensions, which the NCAA is likely to count as time served. But the NCAA could also view him as a repeat violator and punish him further.

In the interim, he could win the national championship.

The perception that college sports are populated by Good Guys and Bad Guys is as old as the NCAA. It adds to the theater of the sport, but is soulless and distasteful—implying, as it does, that half the people involved are amoral brutes with so little self-regard that they believe their only value to the species is as an entertainment product.

The point here is not to referee the argument among fan bases or portray anybody as a victim. It’s that, in a quickly shifting world, the NCAA’s place is unclear. For years, the organization investigated coaches who violated the sacred tenet of “amateurism” by compensating athletes, but now Day is free to tell boosters it will take $13 million in name, image and likeness funds to keep his roster intact, as he did last year.

The rule Stalions broke, like the analyst rule, is a vestige from another time. In-person scouting was banned as a cost-saving measure.

To sum up:

A school can pay one coach $12 million, but it can’t pay 12 coaches a total of $1 million.

If Stalions hires somebody to videotape Ohio State’s signals against another opponent, then that’s apparently illegal, it’s a major strategic advantage (according to the Big Ten) and Harbaugh can be punished because he should have known.

But if Harbaugh then gives all of those signals to Ohio State’s next opponent, that’s within the rules … or is it? Is the recipient also supposed to have known how the intel was acquired? Should Purdue’s Brohm have grilled Ohio State and Rutgers to make sure they obtained Michigan’s signals legally last year?

The Big Ten, by the way, has the right under its sportsmanship policy to punish Ohio State, Rutgers and Purdue for their signs exchange last year, even though they did not violate NCAA rules. The rationale for punishing Harbaugh before the NCAA finished its investigation was that the coach was not being punished for breaking rules; the program was punished to protect “integrity of the competition, civility toward all, and respect, particularly toward opponents and officials.”

For all the fair questions about what happened at Michigan, there are a few that certain principals don’t want to ask.

If an Ohio State staffer breaks a rule and there is no evidence that Day knew, how would he want to be treated?

How would Harbaugh have reacted if the exact same situation had occurred at Ohio State? Would he have demanded due process for Day?

The rivalry has always been fierce. Now it is so contentious that any prospect of collegiality between two members of the coaching profession seems fanciful. Michigan is so convinced that other Big Ten coaches are trying to get Harbaugh fired that its athletic director, Warde Manuel, addressed it in a statement last week: “You may have removed him from our sidelines today, but Jim Harbaugh is our football coach.”

Michigan and Ohio State play The Game once each season, but they play this game with the rule book all year. There is one key difference between this game and The Game, though:

In The Game, somebody wins.

SI senior writer Pat Forde contributed to this article.