NCAA President: Michigan Won National Championship ‘Fair and Square’ Amid Sign-Stealing Controversy

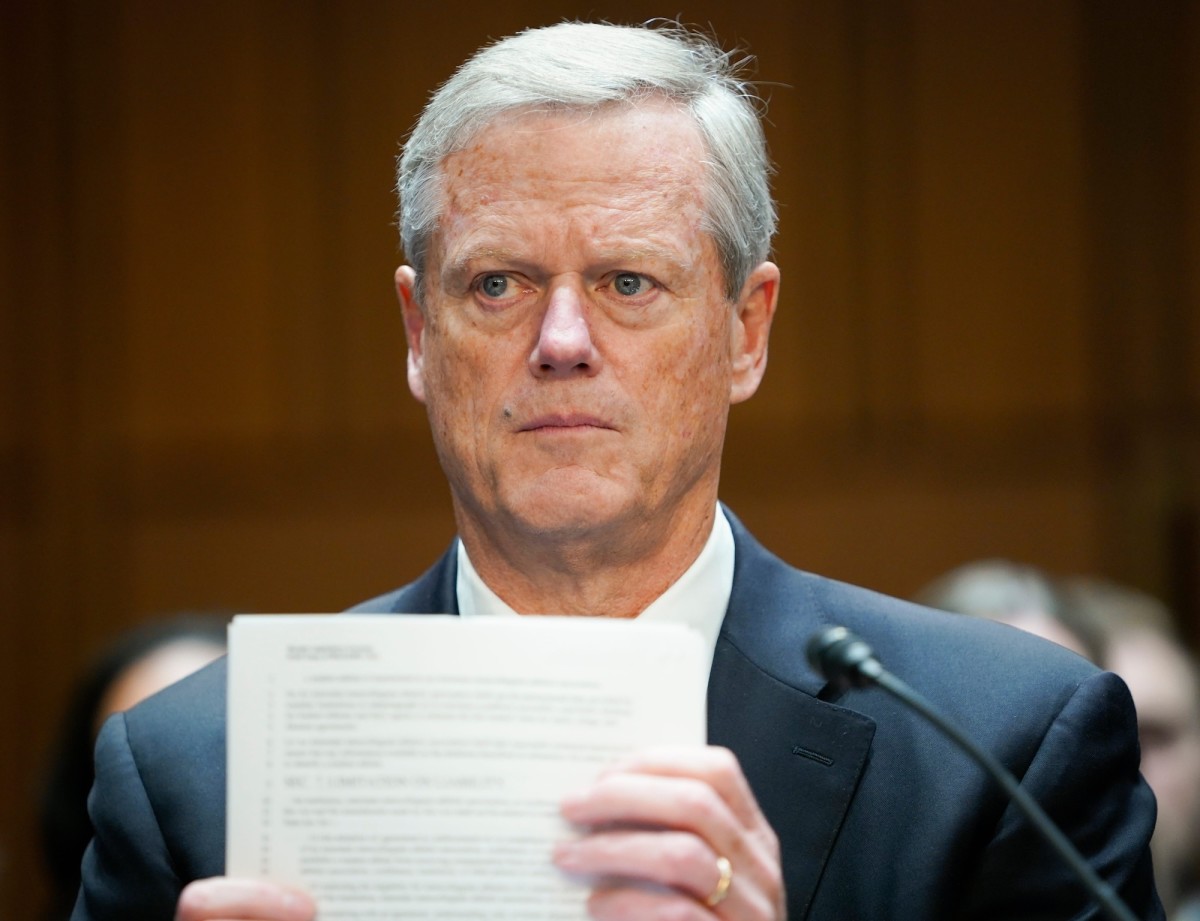

PHOENIX — Nearly 24 hours after Michigan won its first undisputed national championship since 1948, NCAA president Charlie Baker addressed the main controversy of the 2023 college football season—the Wolverines’ alleged sign stealing. Baker shed some light on the association’s early involvement in the situation.

When the NCAA was apprised of former staffer Connor Stalions’s efforts to gather information on future Michigan opponents through advance scouting and video recording, it took the unprecedented step of releasing investigative evidence to the Big Ten and Michigan. Not long thereafter, the bombshell information went public that NCAA enforcement was looking into the undefeated Wolverines.

Baker said he did not know how the information was leaked to the public, but he was “sure” it wasn’t via the NCAA. (Sign stealing is not against the NCAA’s rules, but in-person advance scouting is, as well as using recording devices to document signals.) Once the investigation became public knowledge via a Yahoo Sports report on Oct. 19, Michigan’s season was engulfed in controversy.

“We were approached by a third party who said they had evidence that Michigan was involved in a very comprehensive and unusual sign-stealing scheme,” Baker told reporters Tuesday night, before the start of the NCAA’s annual convention. “We said if you do, you need to come to Indianapolis [where the NCAA is headquartered] and show it to our infractions people. They did. And they showed it to our infractions people, and it was very compelling and so we had to make a decision at that point. And because it was the kind of thing that had consequences to the outcomes of games, we made an unusual decision, which was to simultaneously call the Big Ten and to call Michigan and to tell them about this.”

Some will desire to look back on this season and put an asterisk on Michigan’s title, given the ongoing investigation that loomed over the season. The school’s athletic director, Warde Manuel, declared that notion “ridiculous” after the championship game. Baker said he agrees, in retrospect, that Michigan’s title was earned fairly.

“I don’t regret doing it because sitting on that information, given both the comprehensiveness of it—I think we would have put everyone, including Michigan, in an awful place,” Baker said. “I mean, as it was, it was out in the public domain and people either made adjustments or didn’t. And at the end of the day, no one believes at this point that Michigan didn’t win the national title fair and square. So I think we did the right thing.”

The infractions case moved into the Big Ten’s hands shortly after its existence went public, leading to a controversial suspension of head coach Jim Harbaugh for the last three games of the regular season. The NCAA investigative process moved into the background due to the length of time it takes to process an infractions case from beginning to end. That, Baker said Tuesday, is something the association is addressing.

“We do have a series of discussions going on with the infractions folks about whether or not we can’t do some things to speed up the pace of our investigations,” Baker said. “Because certainly in a case like this, you’d like to be able to move a lot more quickly.”

That’s not a new issue with NCAA infractions cases, some of which have languished for several years before reaching a resolution.

“We’ve heard clearly from the membership that the infractions process does not have credibility when cases last four and five years to resolve,” said Derrick Crawford, vice president of hearing operations at the NCAA, in addressing a seminar on the infractions process Wednesday.

But in contested cases, accelerating the process beyond the usual time frame has proven historically difficult. That’s often due to the school under investigation more than delays on the NCAA front, as those schools seek to mount every possible defense when charged with violations. NCAA vice president for enforcement Jon Duncan is open to ways to speed up the process, while understanding as well as anyone that it’s not that simple.

Duncan pointed out that the vast majority of NCAA infractions cases open and close without anyone even knowing they happened, with an average time frame of four months. And he said that in recent years the average processing of a case has been reduced by more than two months—about 65 days. But more work still can be done.

There is no time frame for resolution of the Stalions investigation—which is the second ongoing investigation of Michigan football. A previous investigation centered on impermissible recruiting during the COVID-19 dead period. Harbaugh was alleged to have lied to NCAA investigators during that inquiry, which resulted in the school suspending Harbaugh for the first three games of the 2023 season.

The case appeared headed for a negotiated resolution before the start of the season, but the Committee on Infractions did not approve penalties that were agreed upon by the school and the enforcement staff. Thus that case appears headed to a contested hearing sometime this year. It’s unclear whether the second infractions case will be rolled together with that one or considered separately.

Either way, the predicament the Wolverines, and specifically Harbaugh, find themselves in is unusual, if not unprecedented. Sources familiar with NCAA infractions cases could not immediately recall a situation in which a coach was charged with Level I violations in separate cases within a year’s time, which could be the fate that befalls Harbaugh.

Already facing a Level I charge (the most severe in the NCAA hierarchy) for allegedly lying to investigators, Harbaugh would be hit with another one if Michigan is charged at that level for Stalions’s spying. Last year, the NCAA adopted a “strict liability” standard for head coaches if their programs run astray of the rules, which would lead to the coach being charged at the same level as the school.

Punishment could vary depending on the coach’s commitment to an atmosphere of rules compliance within his or her program, but Harbaugh would clearly be at risk of being charged as a repeat violator of NCAA rules. The window for that designation is multiple major violations within five years, and the Wolverines could be looking at that designation in consecutive years.

A new rule that was passed Wednesday by the NCAA Division I council could further exacerbate future penalties facing Harbaugh. The council adopted a proposal to increase suspensions of coaches beyond just game days, to include the weeks in between competitions, which would be a significant upgrade—Harbaugh didn’t coach in six games, but he coached every practice leading up to those games.

There has been abundant speculation that Harbaugh will bolt back to the NFL, where he nearly won a Super Bowl with the San Francisco 49ers. Multiple jobs are open and he figures to be a candidate for some of them. He could get out ahead of the NCAA posse … maybe.

Baker declined to answer about what would happen if Harbaugh went to the NFL and the league were to request investigative materials. It is not unprecedented for the league to uphold an NCAA penalty as it did with former Ohio State coach Jim Tressel in 2007 when he attempted to become a consultant with the Indianapolis Colts. Tressel’s work with the franchise was held up for roughly the same period of time he would have been suspended with the Buckeyes, had he remained in college coaching.