The Top 25 Alabama Sports Illustrated Covers

The main goal of the Alabama Sports Illustrated Cover Tournament, which featured a bracket of 48 and took two-plus months of voting, was actually twofold: Determine both a champion and a top 25 list.

After all, this is college football. You have to have a top 25.

This is how BamaCentral voters cast their ballots, based on the round-by-round percentages:

Top 25

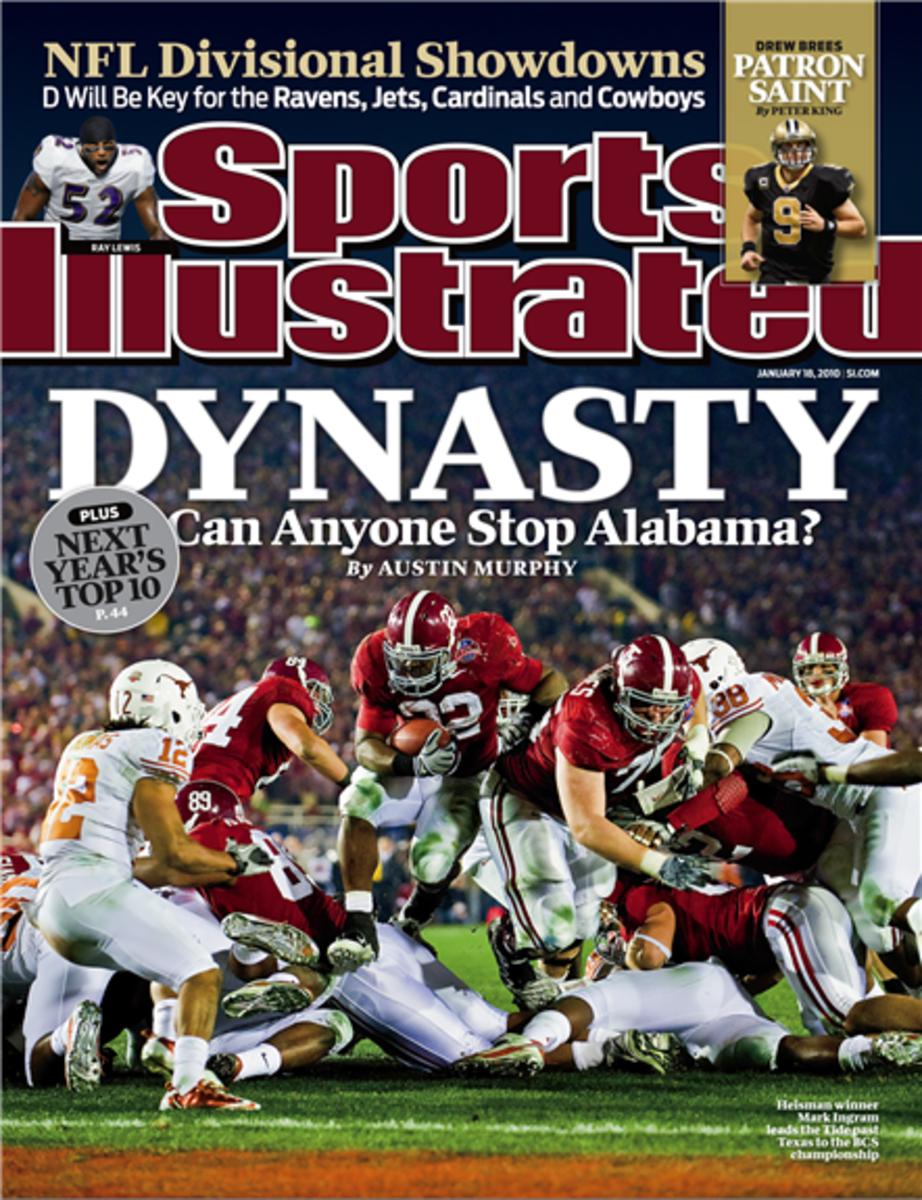

1. Dynasty: Can Anyone Stop Alabama? (2009 title)

Story headline: Staying Power

Subhead: With an earnest coach, a wealth of returning talent, unparalleled recruiting and its chief rival in flux, national champion Alabama is just starting to roll

Excerpt (by Austin Murphy): For the second time in six years the stern-looking coach stood on a stage surrounded by overjoyed athletes, holding a crystal football over his head. As Nick Saban dutifully went down the list of dignitaries he needed to thank, the expression on his face could best be described as a kind of semigrimace. At the pinnacle of his sport after leading Alabama to its first national title in 17 years—a 37-21 victory over a wounded Texas team in the BCS championship game last Thursday night at the Rose Bowl—Saban reminded us that those best equipped to win championships are often the least equipped to celebrate them.

"I guarantee you," said a smiling Terry Saban, as she watched her spouse of 38 years, "he's already thinking about next week."

Did the couple have plans? "He said he'll give me two days," Terry said, "and then he has to meet with some of the players about going out for the [NFL] draft."

Two days? "Two days," she repeated. "And I'll take it."

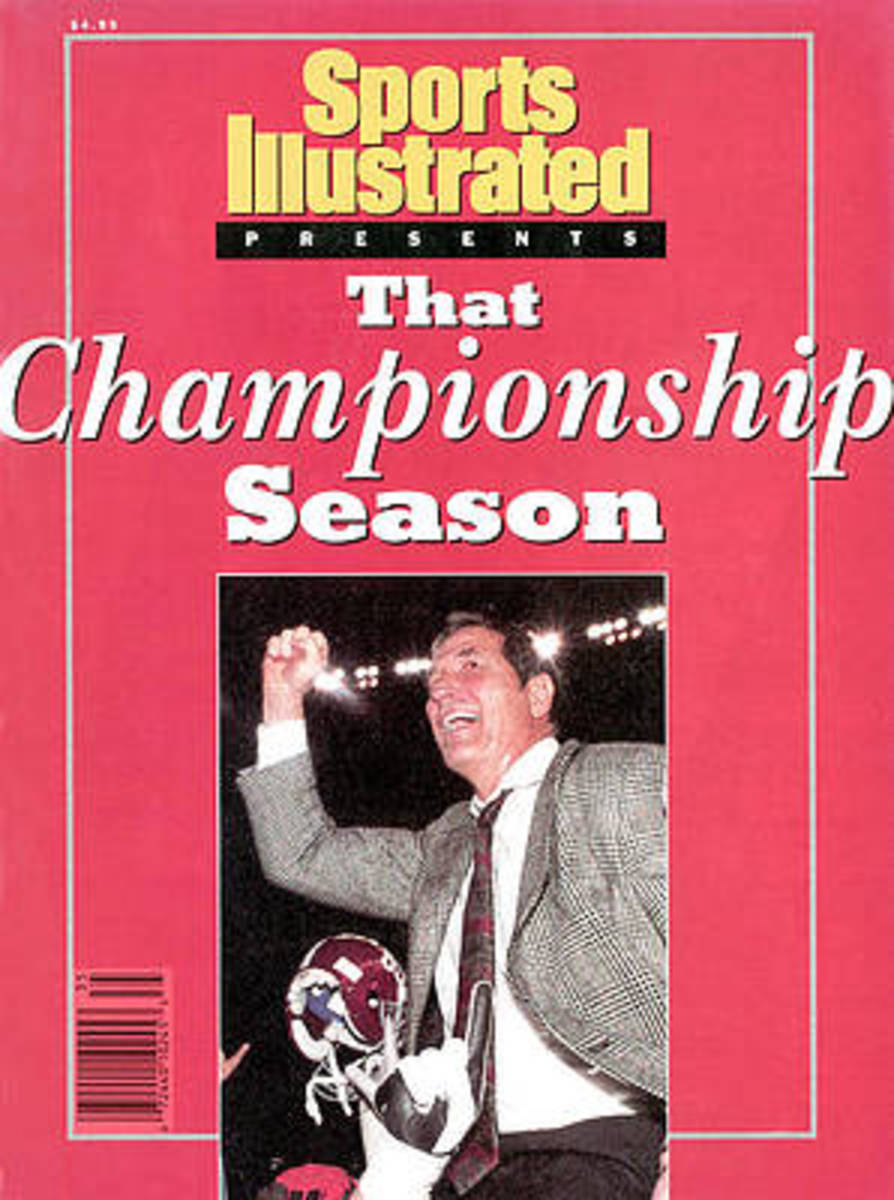

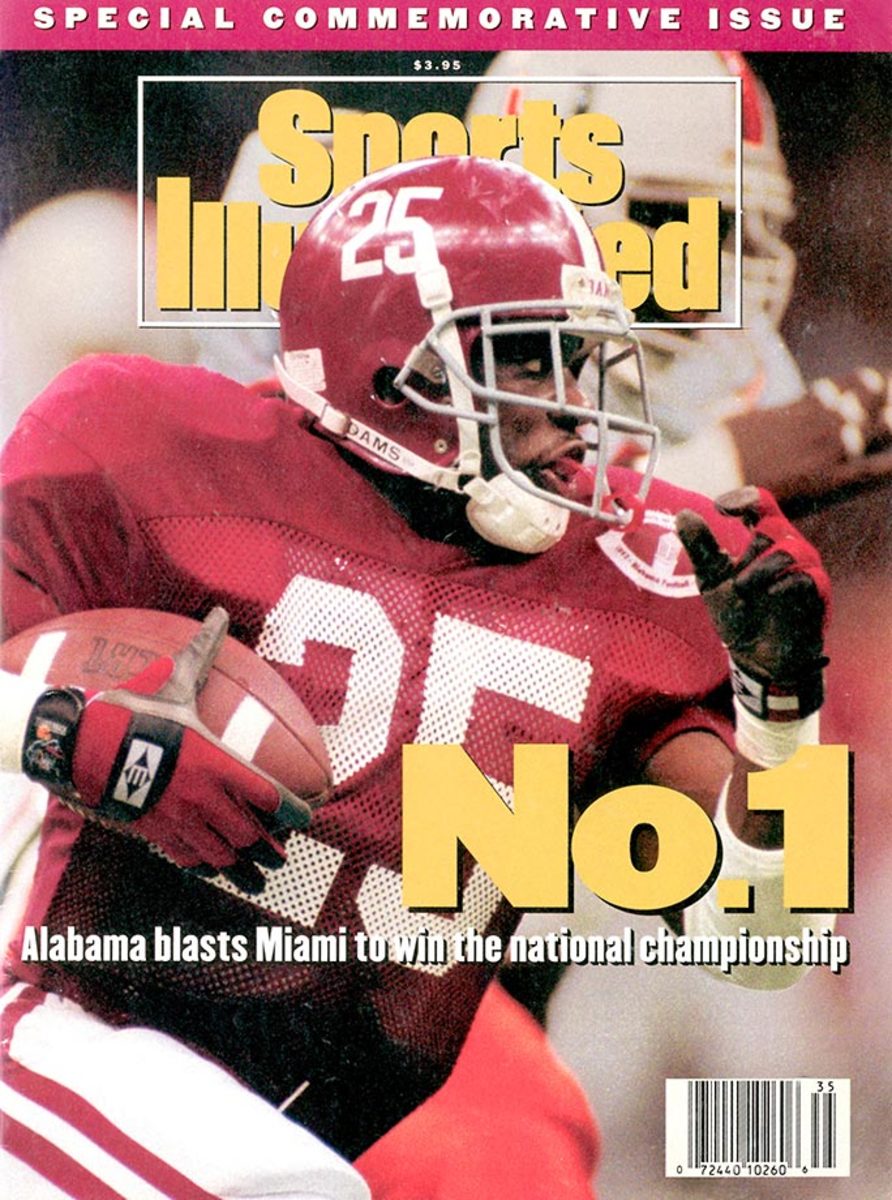

2. That Championship Season (1992)/High Tide in Alabama

This was a dual-cover entry because Alabama didn't appear the cover after knocking off Miami for the 1992 national title. With the game played in the Sugar Bowl on Jan. 1, the next issue wasn't due to hit newsstands until more than a week later, so the decision was made to go with Jim Valvano's fight with cancer. Thus, the creation of commemorative editions.

Story headline: The End of a Run

Subhead: With a resounding 34-13 Sugar Bowl victory, Alabama put a stop to Miami's 29-game winning streak and won its first national title since 1979

Excerpt (by Austin Murphy): Maybe the old man can finally get some rest. Three coaches and one decade to the month after the death of Bear Bryant, Alabama won its 12th national title and its first in 13 years. After biting their lips for a week while the Miami Hurricanes woofed and howled their contempt for the Crimson Tide, the Alabama players dominated and, perhaps more satisfying, muzzled the defending national champions with a 34-13 win in the Sugar Bowl on New Year's. Now that they can once again lay claim to college football's throne, perhaps Tide fans, who have been known to pray for Bryant's resurrection, will let the Bear lie in peace.

Pay no attention to Alabama coach Gene Stallings's stubborn refusal in the days leading up to the game to concede that his team was an underdog. This was an upset of magnificent proportions. Crimson Tide quarterback Jay Barker could not be counted on to pass his team to victory, and, in fact, he would complete only four of 13 throws for 18 yards and suffer two interceptions. Likewise, the outside running game would be an exercise in futility. As long as Jessie Armstead, Micheal Barrow and Darrin Smith have started at linebacker, no team has been able to turn the corner on Miami.

Alabama would have to run between the tackles—football's truck route—behind a smallish, undistinguished line that, until recently, 'Bama fans had maligned. At 6'3" and 250 pounds, center Tobie Sheils is slight for a major-college lineman. Left guard George Wilson shot off half of his left foot in a 1989 hunting accident. And six nights before the game, right tackle Roosevelt Patterson was verbally assaulted in the French Quarter. "You must be an offensive lineman, you fat, sloppy ——," Miami linebacker Rohan Marley had shouted at the amply padded, 290-pound Patterson.

Chalk one up for the shrimp, the gimp and the blimp. Behind them, Derrick Lassic rushed for 135 yards on 28 carries, the most yards a back gained against the Hurricanes this season. "They said we were one-dimensional," said Sheils after the game. "We are one-dimensional. Sometimes you only need one dimension."

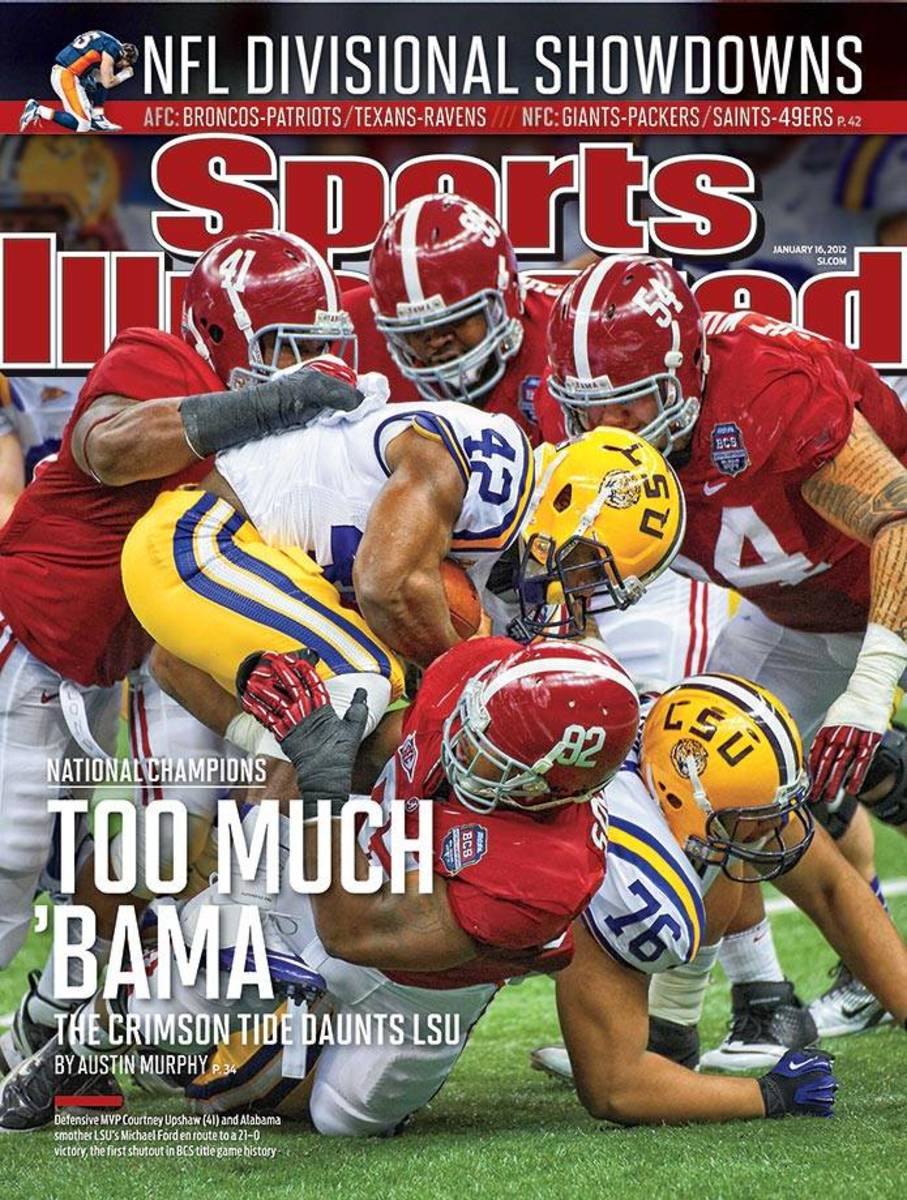

3. Too Much Bama (2011 title)

Story headline: Absolutely Alabama

Subhead: In a defensive tour de force that featured just enough offensive punch (a touchdown, at last!), the Crimson Tide shut down LSU and left no doubt as to whom should be crowned national champion

Excerpt (by Austin Murphy): Alabama's 14th national championship, its second in three years, did more than remove the sting of that home loss to the Tigers on Nov. 5. The title was a balm and a gift to the thousands of residents of Alabama who lost property and loved ones in the tornadoes that ripped through the state on April 27. "This isn't a win just for us, but this is a win for Tuscaloosa and all of Alabama," said a teary Carson Tinker, the team's long snapper, who was with his girlfriend, Ashley Harrison, when she was swept up by a twister and thrown roughly 100 yards. Harrison died, her neck broken. "We've been through so much this year, and I'm at a loss for words to describe what I feel. Just happy."

BCS to the U.S.A.: You're welcome!

This, after all, was the matchup the entire nation clamored to see—with the exception of the roughly 80% of Americans who don't live in a state with an SEC school and don't affix, for instance, Bulldogs or Gators or Razorbacks magnets to their car doors. We've seen this movie before, went the thinking among non-SEC types, who pointed out that Alabama already had a crack at the Tigers and lost in the so-called Game of the Century, which was renamed upon its conclusion Field Goal Fest '11.

Among those eager for the rematch was SEC commissioner Mike Slive, who could rest assured, once the title game pairing was announced, that his conference was guaranteed its sixth straight national championship. (The bad news: An SEC team was now sure to lose in the title game for the first time in the 14-year history of the BCS.)

4. Promised Land: The Alabama Dynasty Rolls on (2015 title)

Story headline: This One Is Special

Subhead: An audacious onside kick. An electrifying kickoff return. A breakout by an underused tight end. Alabama needed something beyond its usual formula to hold off Clemson, but the end result was familiar: a fifth national title for coach Nick Saban

Excerpt (by Andy Staples): Nick Saban's game face typically ranges from stone to snarl, but the corners of his mouth turned north even as his team remained deadlocked with Clemson in the fourth quarter of Monday's national championship game. Was it relief? Joy? Or a knowing smirk?

At the team's hotel earlier in the day Saban had told Crimson Tide junior kicker Adam Griffith to be prepared to execute the pop kick onside protocol against the Tigers. Saban had noticed on film that when Clemson expected the ball to be booted deep into the corner, the Tigers squeezed to one side of the field. When Clemson lined up that way several times on Monday, Saban knew the pop kick could work — as long as freshman defensive back Marlon Humphrey, the play's target, didn't drop the ball the way he had in the Tide's walk-through practice. Tied at 24, with his defense panting from chasing Clemson sophomore quarterback Deshaun Watson — who was dazzling with 405 yards passing and 73 on the ground— Saban decided Alabama needed to gamble. "He pushed all the chips in," strength and conditioning coach Scott Cochran growled later.

Griffith tapped the ball skyward in a perfect arc. Humphrey, with nary a Clemson player in arm's distance, caught it on the 50, unleashing a (brief) grin from Saban. "He told us we're not allowed to smile during games," special teams coordinator Bobby Williams cracked. Two plays later senior quarterback Jake Coker hit junior tight end O.J. Howard down the left sideline for a 51-yard touchdown. The Tide had wrested the momentum away from a worthy opponent, and Alabama gutted out a 45-40 win to claim its fourth national title in seven seasons. Saban, who also won the 2003 title at LSU, moved one behind Bear Bryant, who won six championships. Saban brushed off questions about one day surpassing the Tide icon, but he couldn't hide his pride in a team that was written off in September but rose to win a title anyway, using a mix of new and old schemes and an attitude that has produced champions for as long as games have had scoreboards.

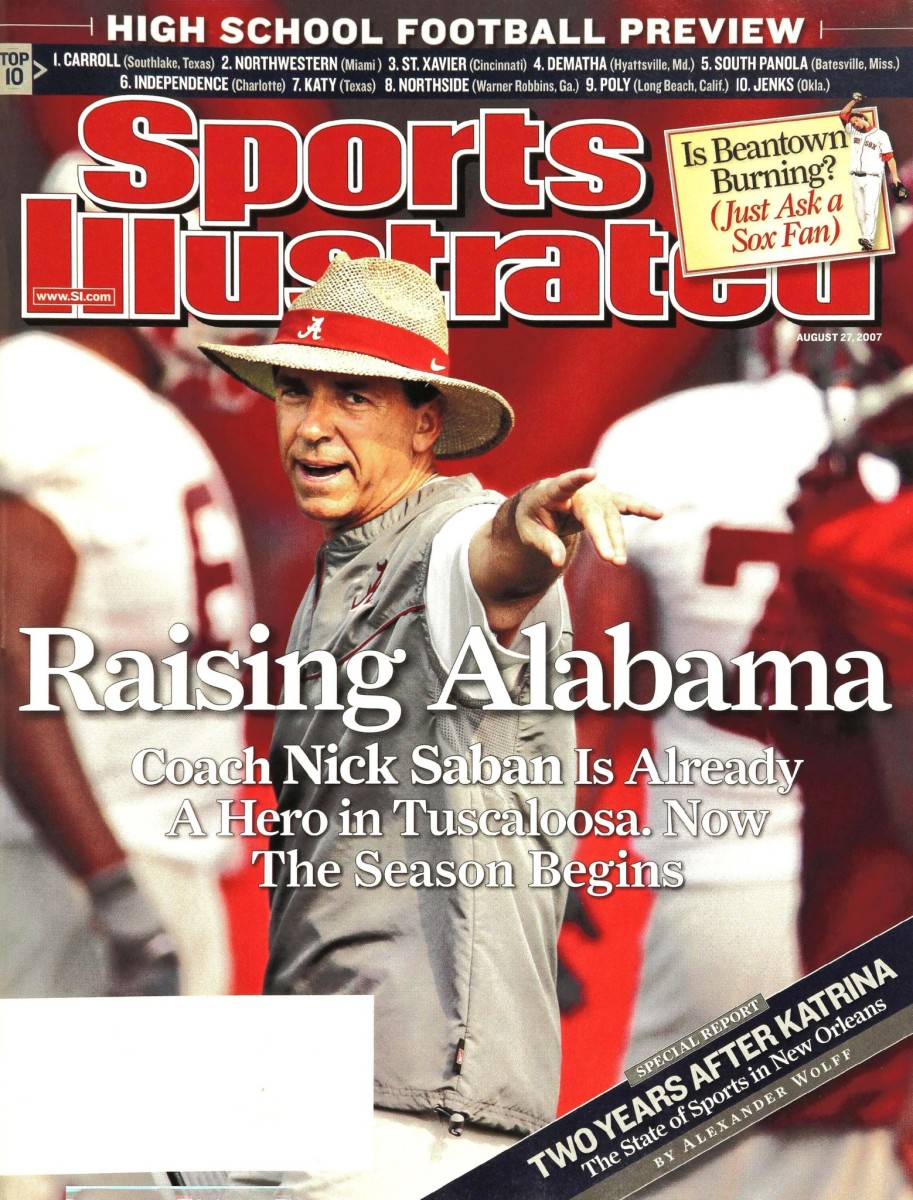

5. Raising Alabama (Nick Saban)

Story headline: In the Nick of Time

Subhead: Fed up with mediocrity and losing to Auburn, the Alabama faithful welcome Nick Saban as a coach tough enough to bring back the glory of the Bear

Excerpt (by Rick Bragg): They say college football is religion in the Deep South, but it's not. Only religion is religion. Anyone who has seen an old man rise from his baptism, his soul all on fire, knows as much, though it is easy to see how people might get confused. But if football were a faith anywhere, it would be here on the Black Warrior River in Tuscaloosa, Ala. And now has come a great revival.

The stadium strained with expectation. The people who could not find a seat stood on the ramps or squatted in the aisles, as if it were Auburn down there, or Tennessee, and when the crowd roared, the sound really did roll like thunder across the sky. A few blocks away 73-year-old Ken Fowler climbed to his second-story terrace so he could hear it better and stood in the sunlight as that lovely roar fell all around him. He believes in the goodness and rightness of the Crimson Tide the way people who handle snakes believe in the power of God, but in his long lifetime of unconditional love, of Rose Bowl trains, Bobby Marlow up the middle and the Goal Line Stand, he never heard anything like this. His Alabama was playing before the largest football crowd in state history, and playing only itself. "We had 92,000," he said, "for a scrimmage."

It felt good. It felt like it used to feel.

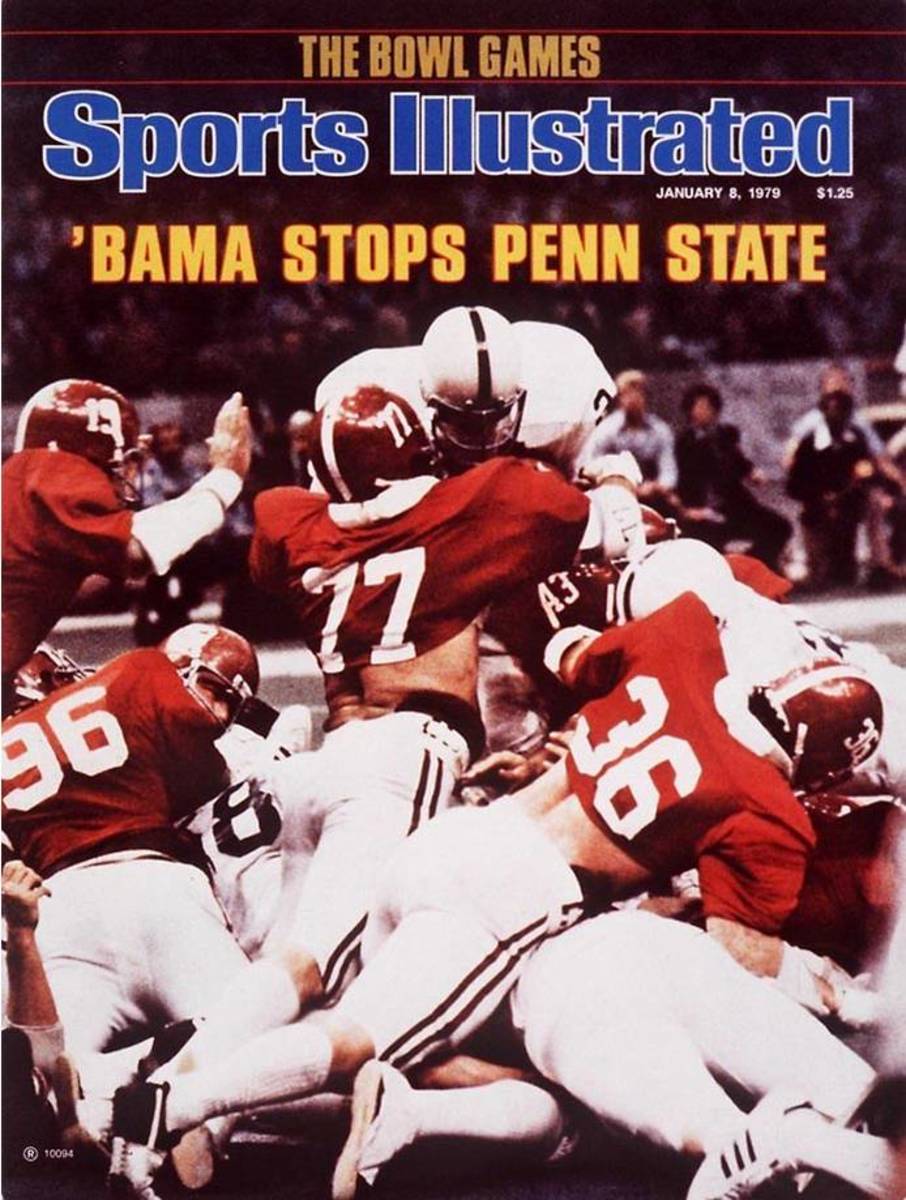

6. Bama Stops Penn State

Story headline: The Rising of the Tide

Subhead: Alabama beat Penn State 14-7 in the Sugar Bowl to lay claim to the national title

Excerpt (by John Underwood): On the day before his Sugar Bowl showdown with Penn State, Bear Bryant breakfasted in the elegant refuge of his hotel suite high above New Orleans on a floppy-looking egg-and-bacon sandwich (brought up in a brown paper bag) and coffee in a Styrofoam cup. Between swallows the Bear was saying that if there was one thing you could be sure of about his Alabama defense it was that you couldn't be sure of his Alabama defense. It had been great at times and unsound at times, and that's "not recommended" when you play the No. 1 team in the nation, one that had not lost in 19 games.

Bear noted that the Tide defense had been hurt a lot. That it had been particularly slowed in the secondary by those injuries, and by, well, being slow in the secondary. And that it was about to go under the gun against a quarterback, Penn State's Chuck Fusina, whom Coach Joe Paterno called the best passer he ever had. The situation fairly cried out for a dedicated, if not wild-eyed, pass rush, and "rushing the passer is the thing we do worst," said Bryant.

As for the Alabama fans who were establishing themselves as No. 1 in whoops and hollers downstairs in the hotel and up and down Bourbon Street, Bryant said he wished they'd be quiet until after the game.

Well, Bear, you can come down now and join the merry group. And bring the defense with you. On second thought, have them bring you.

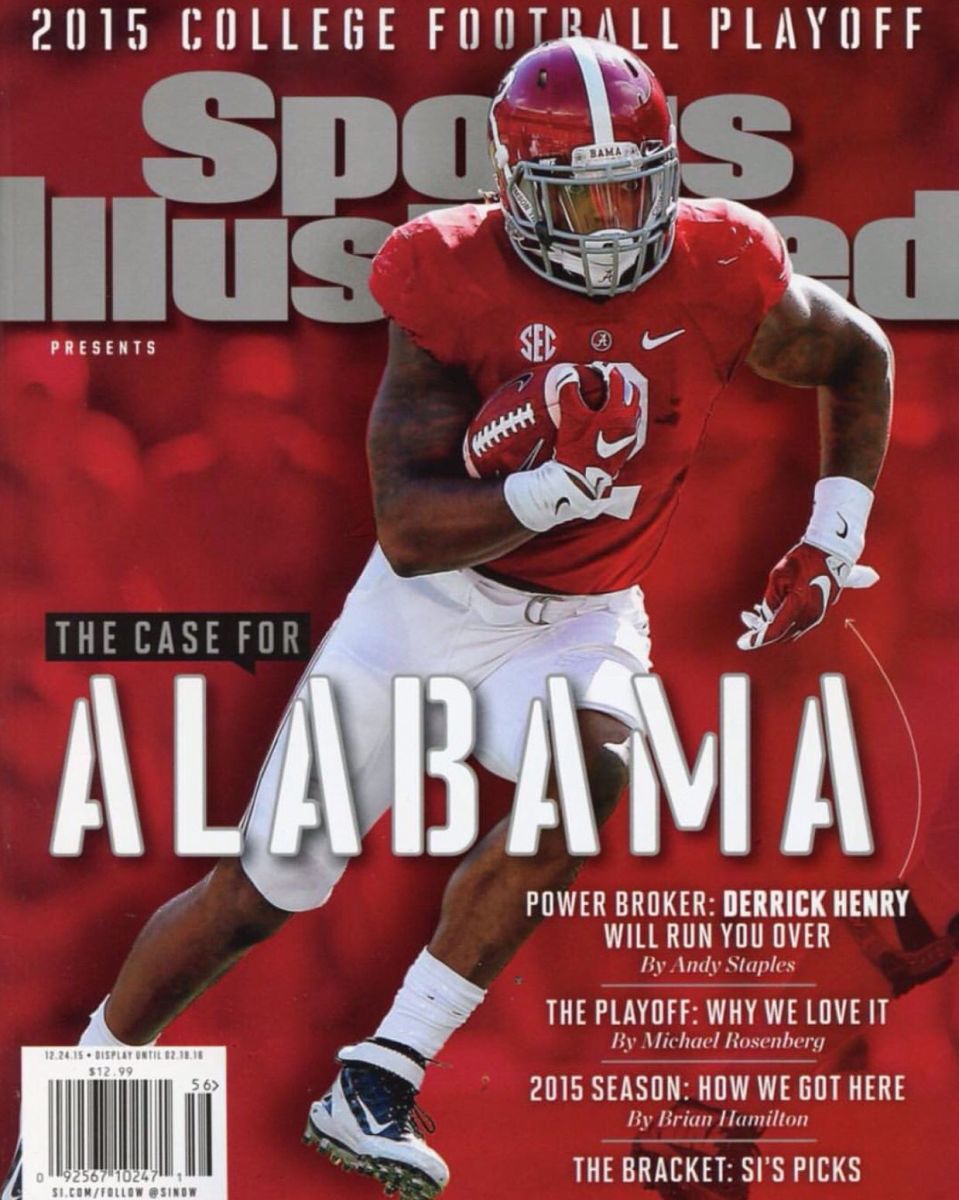

7. Power Broker: Derrick Henry Will Run You Over

Story headline: Maximum Impact

Subhead: No back gets more mileage out of brute force than Alabama junior Derrick Henry, who hits the hole like a freight train as he reduces some of the most hallowed rushing records to dust

Excerpt (by Andy Staples): Bobby Ramsey saw the look every day at practice for four seasons. The Yulee (Fla.) High coach also saw it on Friday nights in the fall. Now he sees it when he watches Alabama play. The look, Ramsay says, mixes a hint of fear with heaps of resignation and a trace of dread. No matter whether the player is bound for the NFL or the LSAT, would-be tacklers all appear the same when 6'3", 242-pound junior Derrick Henry takes a handoff and hits the hole: Their shoulders slump, faces sag and bodies tense in anticipation of the collision to come.

"It's more like thrusting yourself into something you know is going to be unpleasant, but you do it anyway," says Ramsay, who coached Henry from 2009 to '12. "Then you're hanging on for dear life. Then you're going back to the huddle thinking, I have to do that again?"

Ramsay knows this look well because three years before Henry broke Herschel Walker's 34-year-old SEC single-season rushing record with 1,986 yards—and counting—to become a Heisman Trophy finalist, he finished his Yulee career with 12,212, crushing Ken (the Sugar Land Express) Hall's 59-year-old national high school mark. Ramsay also knows how a Henry run feels because he stood directly behind the linebackers when the Hornets did full-contact running drills. "The only thing I can equate it to," Ramsay says, "is standing on the sidewalk and a jeep goes by doing 40."

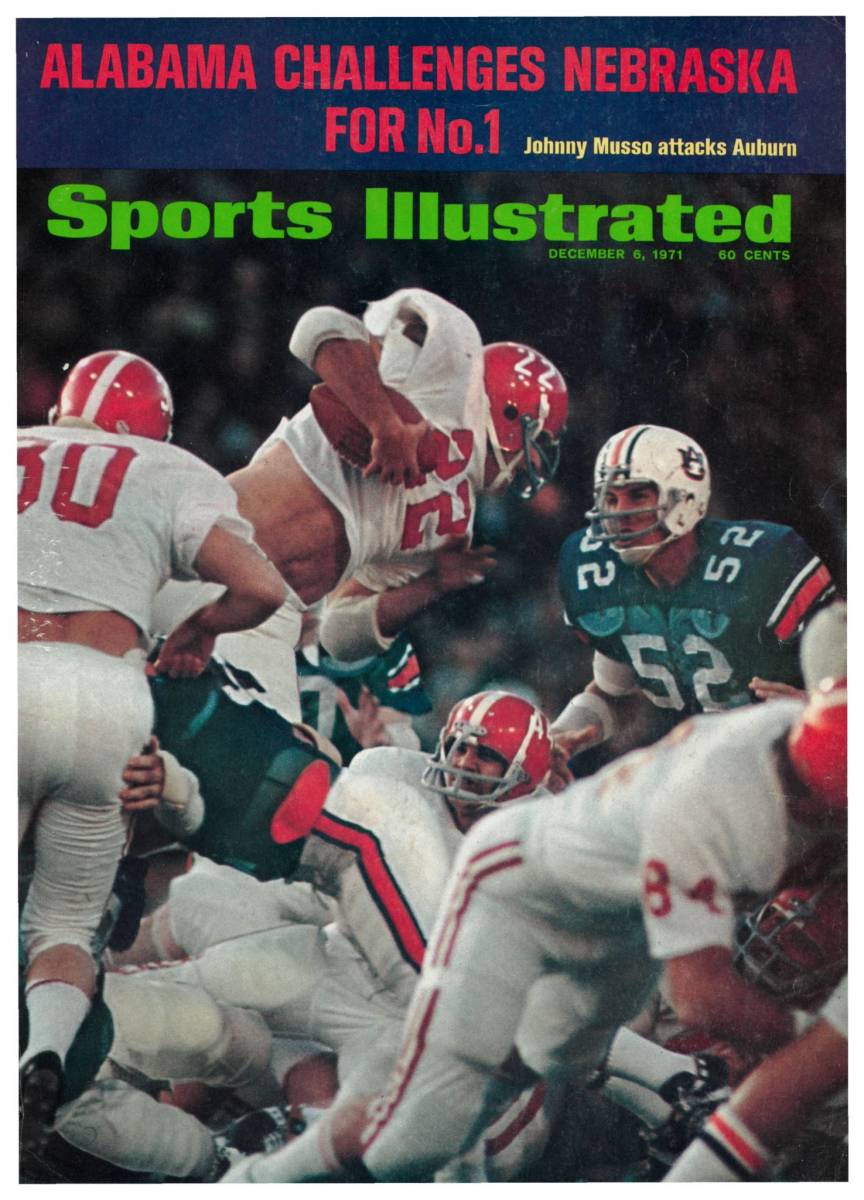

8. Johnny Musso Attacks Auburn

Story headline: Alabama Poses Another Threat

Subhead: Alabama Challenges Nebraska for No. 1

Excerpt (by Pat Putnam): The pattern of the game was set early, to Bryant's delight and Jordan's dismay, and it never varied. When Auburn had the ball it was harassed badly. When Alabama had it, it kept it. And kept it. And kept it. Auburn had possession just 18 minutes and 11 seconds, lost one fumble and had two of Heisman Trophy winner Pat Sullivan's passes stolen, and managed but 179 yards. Before Alabama, the Tigers thought they were having an off day if they didn't gain more than that in one quarter. "One thing we have to do," Bryant had said, "is control the ball." Control it? Alabama owned it; owned it for a fantastic 41 minutes and 49 seconds, and most of the time it was hurtling through the Auburn defenses in the arms of Johnny Musso (see cover), who was running on a disjointed big left toe that would have put a lot of other running backs on crutches.

Three weeks ago, against LSU, Musso's big toe was wrenched from its socket, and from then until he started against Auburn the best the 196-pound All-America senior halfback could manage was a half-speed limp in tennis shoes. And he couldn't even do that until three days before the game. When Alabama went through its final light workout on Friday, Musso watched from the sidelines in street clothes. In nine games he had scored 14 touchdowns and gained 921 yards. With that toe, he didn't figure to gain 921 inches against Auburn's band.

"Don't worry," said the handsome 21-year-old. "I'll play. I've got this gadget Trainer Jim Goostree rigged up for me." And he held up a red plastic cast that had been molded to fit his foot. "I'll just tape it on and away I'll go. Auburn has this banner out that says: STOP THE WOP. I've got one hanging over my bed." He smiled thinly. "I'm going to be there to give them a chance."

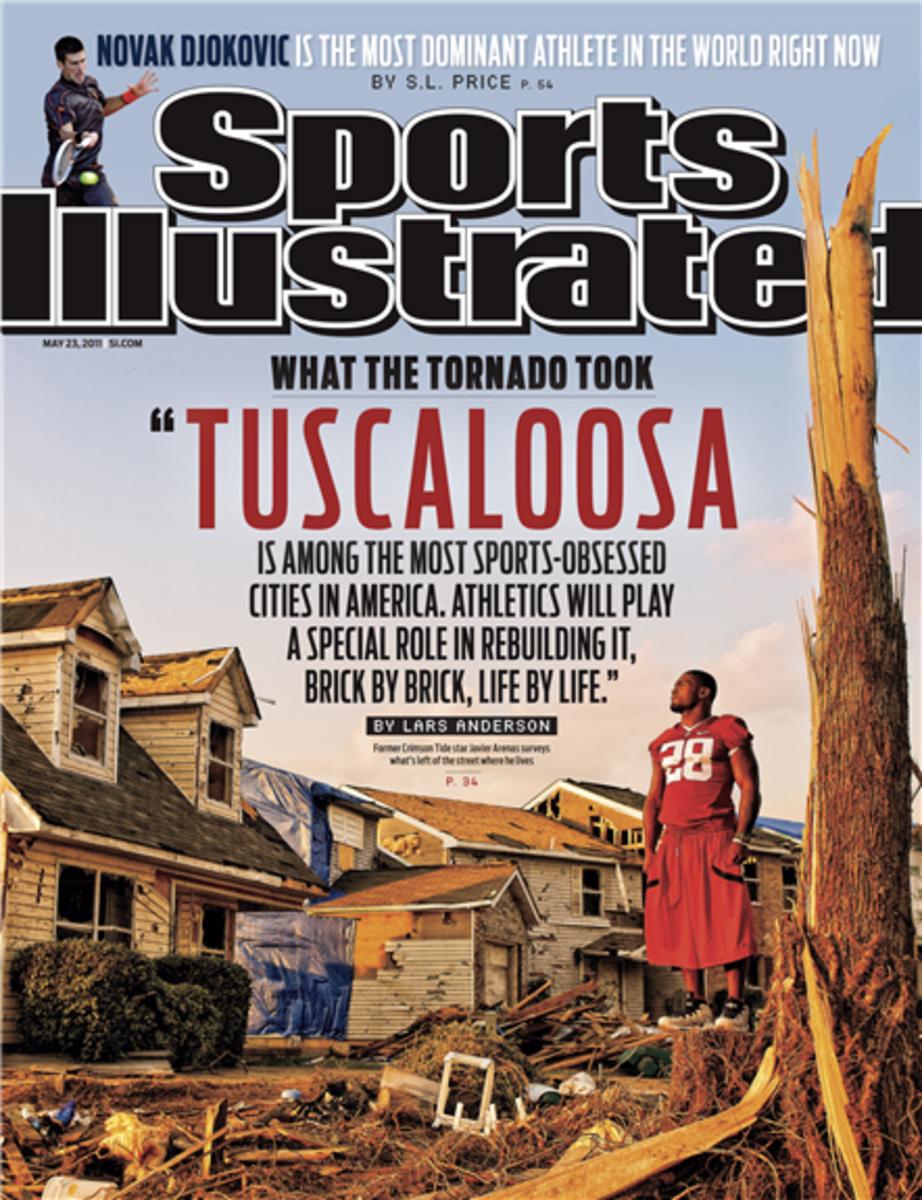

9. What the Tornado Took

Story headline: Terror, Tragedy and Hope in Tuscaloosa

Subhead: On April 27 the most devastating tornado in Alabama history cut nearly a mile-wide swath through the university town, killing 41. Crimson Tide athletes, haunted by the storm and its aftermath, work to heal a community that has always cheered them on as they try to put their own lives back together

Excerpt (by Lars Anderson): How do you tell the story of the deadliest tornado in the history of Alabama? As of Sunday, 41 were confirmed dead—including six students from the University of Alabama—and hundreds injured in Tuscaloosa and Tuscaloosa County alone. (A total of 238 people were killed by more than 60 tornadoes that ravaged the state on April 27.) But these raw numbers can't begin to account for the damage. Nearly every resident in the town of 90,000 has trouble sleeping, and when they do close their eyes and drift away, most are tormented by please-God-wake-me nightmares.

I live in Birmingham and from my front porch saw the same twister that decimated Tuscaloosa pass five miles to the north. Debris with Tuscaloosa markings—letters, business cards, pictures—fell in my neighborhood, which is 60 miles from T-town. My dreams, too, have been haunted by the images of destruction and despair I've seen in Tuscaloosa, where I taught a sportswriting class at the university this spring. None of my 14 students were physically harmed—though it took days of frantic texting and e-mailing to verify that as cellphones and Internet connections failed throughout Alabama—but the storm continues to swirl inside of them, deepening their emotional scars.

"The tornado cut a six-mile path through here that was a half mile to a mile wide," says Tuscaloosa mayor Walt Maddox as he looks at the ruins of a grocery store where his mother took him shopping as a boy. "Fifteen thousand people here were in the path of this thing. The enormity of it all can swallow you."

The most iconic structure in the state, Bryant-Denny Stadium, looms in the distance, dominating the battered T-town skyline. The tornado passed just a half mile south of the campus. "If it hits us," says Anthony Grant, the Crimson Tide men's basketball coach, "this place would have been shut down for several years. Who knows? Maybe longer."

10. Fresh Heir (Tua Tagovailoa)

Story headline: It Takes Tua

Subhead: A bold coaching decision. A furious second-half comeback led by a true freshman. A stunning missed field goal. A miracle overtime TD pass. The Crimson Tide had to dig deeper than usual to beat Georgia and win Nick Saban's record-tying sixth national title.

Excerpt (by Andy Staples): He held his headset in his hands, and if he hadn't needed it, he might have thrown it all the way from Atlanta to Tuscaloosa. Alabama coach Nick Saban had put the ball in the hands of a backup true freshman quarterback (by choice). That quarterback was protected by a true freshman left tackle (by necessity). Now, down three in overtime of the national title game, those two had produced a disaster.

Tackle Alex Leatherwood had replaced injured starter Jonah Williams in the third quarter. Leatherwood had played well until Alabama's first offensive snap of overtime, when he let Georgia linebacker Davin Bellamy slip past. Bellamy chased Crimson Tide quarterback Tua Tagovailoa, who had replaced starter Jalen Hurts to start the second half, backward. Bellamy dived and missed, but teammate Jonathan Ledbetter joined the pursuit. Tagovailoa kept backpedaling. Tagovailoa scrambled the wrong way so long that Bellamy had time to get up, chase again and sack him for a 16-yard loss.

But the great thing about freshmen is, they don't know what they don't know, and Tagovailoa didn't seem to grasp that the sack was supposed to doom his team.

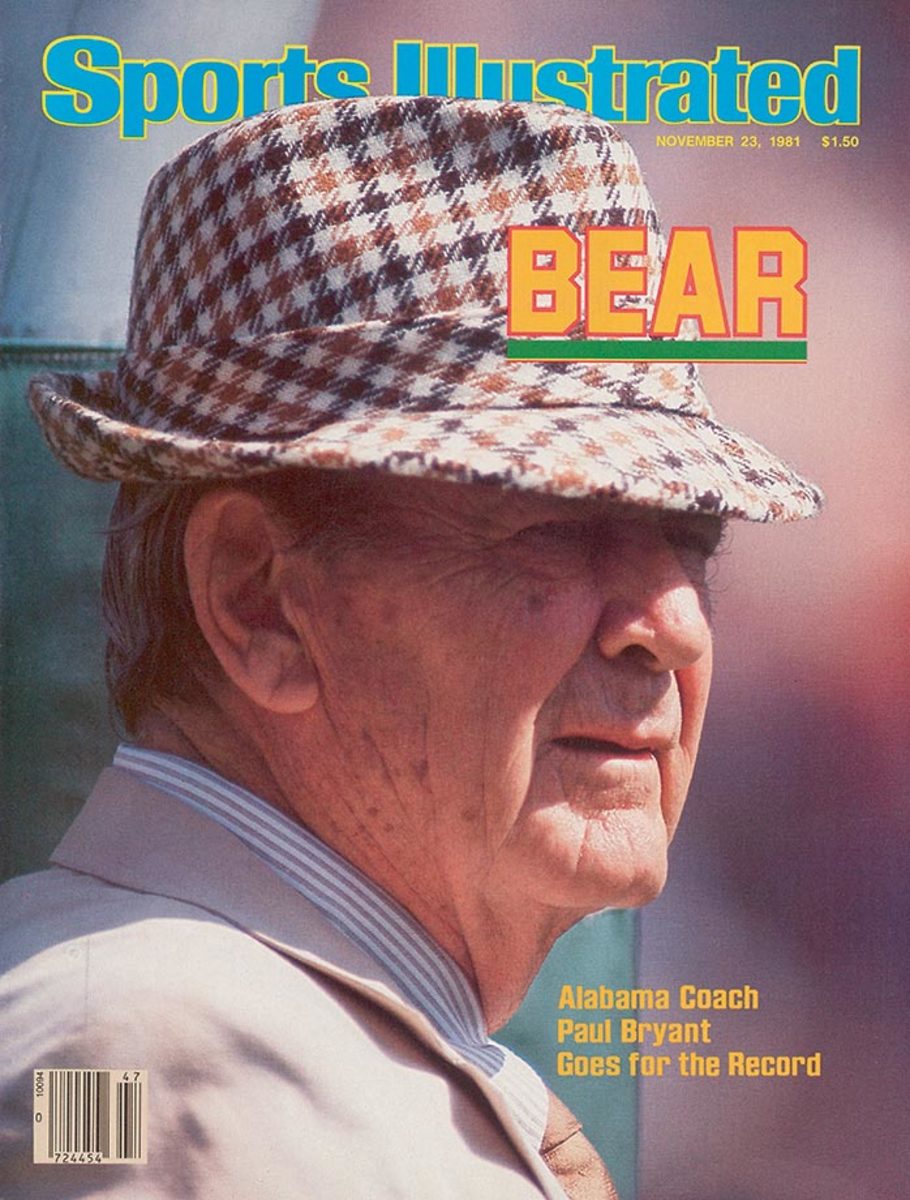

11. Bear: Bryant Goes For the Record

Story headline: 'I Do Love The Football'

Subhead: Bear Bryant says that unequivocally after 43 years of coaching and 314 wins, tying Stagg's record, which he can break against Auburn

Excerpt (by Frank Deford): The pigskin historian begins to sort through the mounds of evidence that are supposed to add up to the man who is identified as Coach Paul (Bear) Bryant. It is all there, in layers, by now a folk chronicle, each tale told and retold in nearly the same language every time, and all irrespective of relative importance, time or place: The Bear and his humble origins in Moro Bottom, near Fordyce, Ark.; The Bear at Alabama as "the other end" opposite the immortal Don Hutson; the tales of how The Bear got his name (accounts provided by every possible eyewitness, save perhaps the noble ursine itself); The Bear and the bowls; The Bear and the record—Amos Alonzo Stagg's 314 victories as a coach, which Bryant tied last Saturday with a 31-16 defeat of Penn State and could surpass next week against Auburn; The Bear that first hellish summer in Aggieland; The Bear returns to his Alabama; The Bear and his hat; The Bear and The Baron; The Bear walks on water (and other fables); the ages of The Bear.

By now, it is all so blurred, yet all so neat. The more one reads—the more one suffers through the same stuff from The Bear and his hagiographers—the more one understands a friend of The Bear's, a Tuscaloosa physician, who says, "That he mumbles really doesn't matter to me anymore, because by now, I always know what he is going to say, anyway."

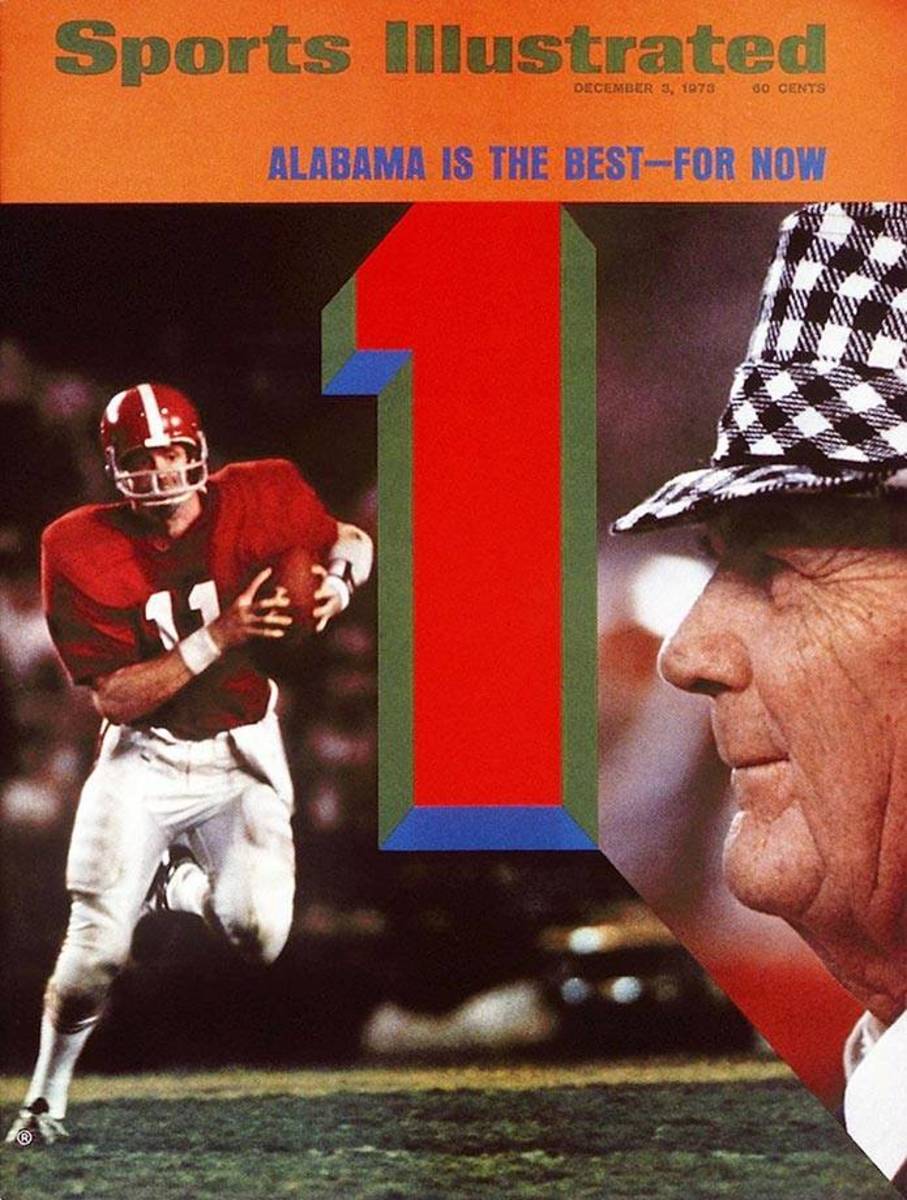

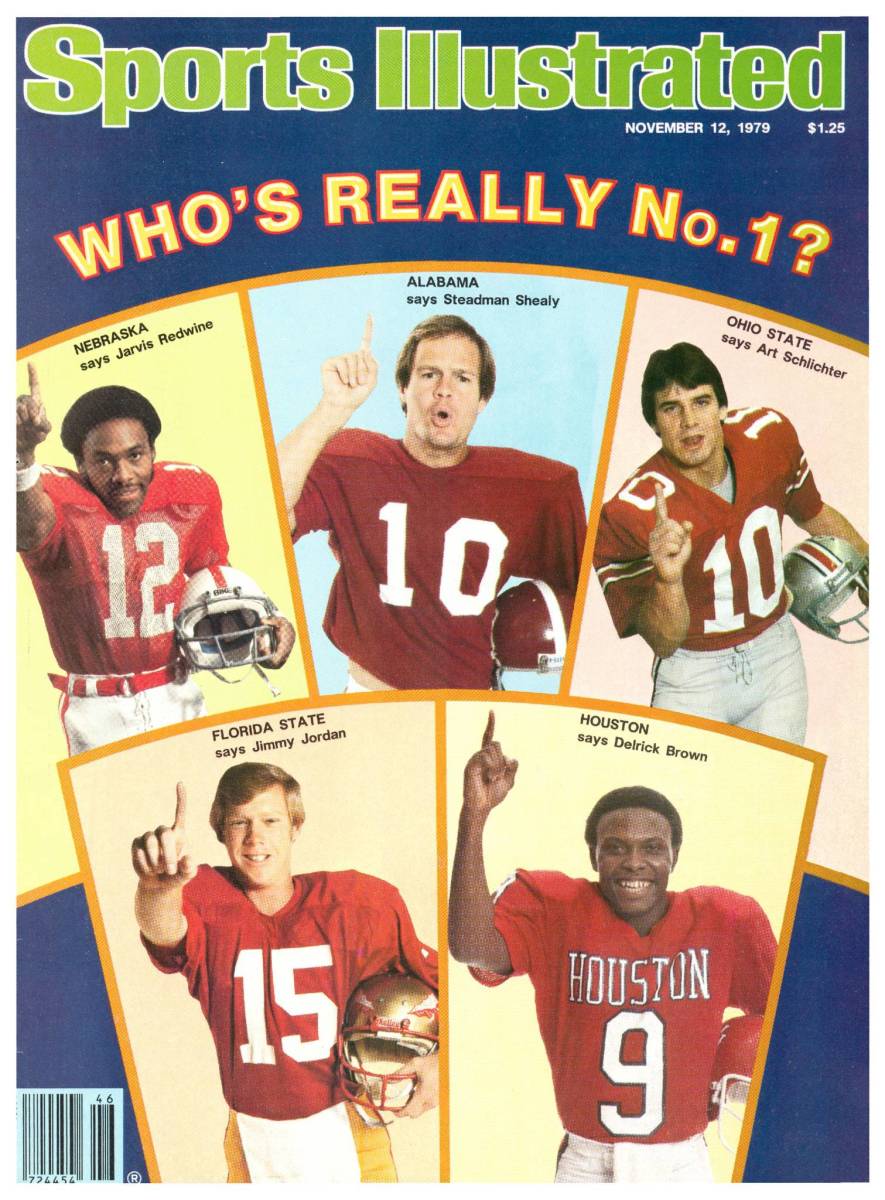

12. Alabama Is The Best, For Now/Who's Really No. 1?

This was another dual-entry:

Story headline: Bama Takes Charge

Subhead: The Crimson Tide has moved ahead in the race for the national championship, thanks to the Ohio State-Michigan tie, but one false step and Notre Dame, Oklahoma and Penn State are poised to pounce

Excerpt: When Bear Bryant brought the Crimson Tide to Baton Rouge last week, the mist had not settled on the bayous before he and LSU's Charlie McClendon were bragging on one another again. It is a gracious Southern ritual that has been going on since McClendon, who is not only a fellow traveler from Arkansas but played and coached under Bryant, took over LSU in 1962.

According to the script, Bryant puts on his most venerable face and then will say as he did last week, "Cholly Mac and I are good friends, as everyone knows, and I hope he'll be kind to his old coach." Then, after Bryant's boys waylay McClendon's, as they have done seven times in nine meetings, Cholly Mac will drawl, "Somehow, I don't think Bear taught me all he knows."

There were hints of that last week when Bryant rightly prophesied that "mistakes will decide this game." ABC made the first one when it scheduled the game for prime time only to find that it would be bucking heads with NBC's offering of My Fair Lady. So, pulling strings again, ABC rescheduled the kickoff for the odd hour of 5:35 p.m. "As cute as Bear Bryant is," said one ABC operative, "he can't match Audrey Hepburn."

Bonus cover: There's a Red Alert

By Douglas S. Looney: In the debate over who's on top—Alabama, Nebraska, USC, Ohio State, Houston or Florida State—one point is clear: No. 1 wears red.

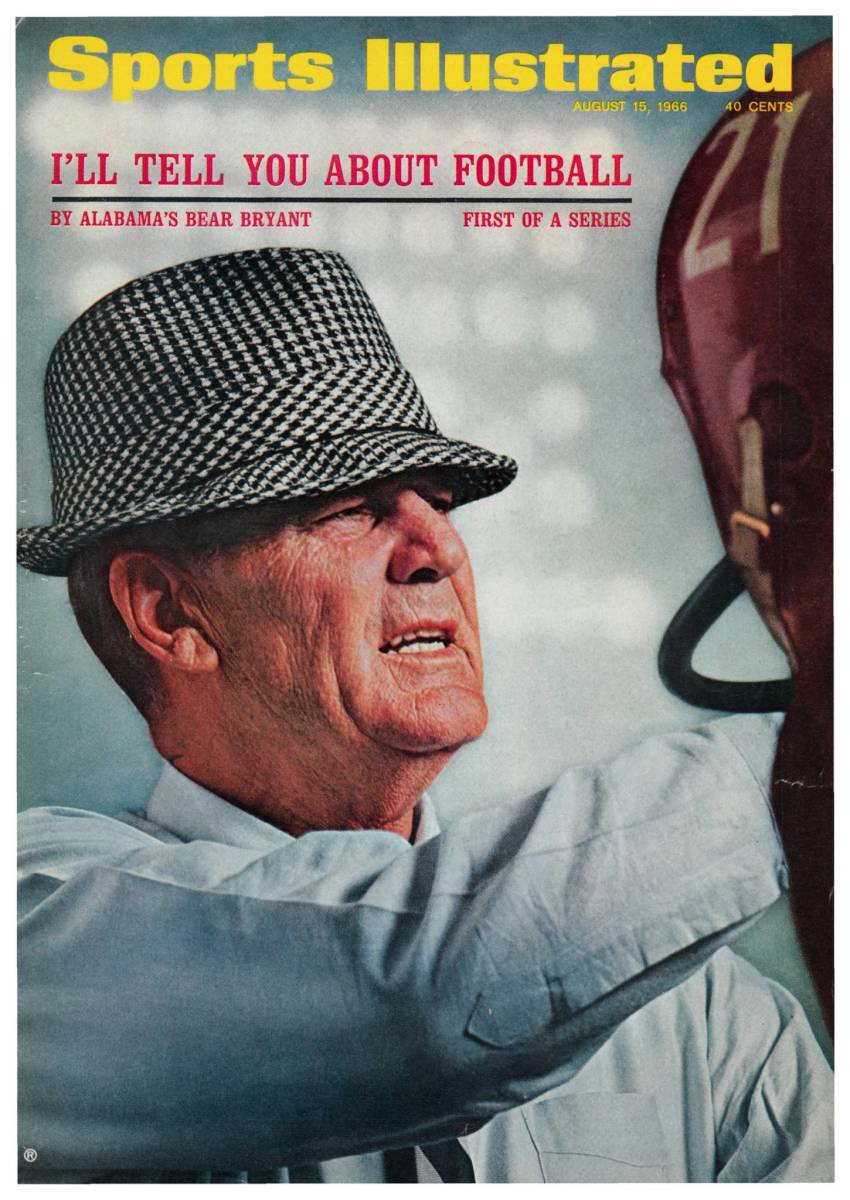

13. I’ll Tell You About Football (Bryant)

Story headline: I Know I’ve been motivated all my life

Subhead: Bear Bryant is the most successful and controversial college football coach in the nation. His Alabama teams – aggressive on offense, ferocious on defense and conditioned in the boot camp that Bryant calls a practice field – have been national champions three of the last five years, have appeared in a bowl game in each of the last seven and, since Bryant arrived eight years ago, have won 69 games, lost 12 and tied six …

Excerpt (with John Underwood): Well, like I say, I’ve done some stupid things and made some stupid decisions. I quit Kentucky because I got a mad on and made up my mind it just wasn’t big enough for me and Adolph Rupp, and that was for sure stupid.

I can tell you a lot about quitters. I used to have a sign at Kentucky: Be good or be gone. Jerry Claiborne used to say he had a different roommate every day. I don’t have that sign anymore. Don’t believe it’s necessary now, because I don’t believe you can categorize every boy who quits football as a quitter. For some it’s a matter of finding other interests, just like switching courses. But, from the time I played at Alabama until a few years ago, I believed that if you weren’t a winner, if the game didn’t mean enough to you, you’d probably end up quitting. So I’ve laid it on the line to a lot of boys. I’ve shook’em, hugged’em, kicked’em and embarrassed them in front of the squad. I’ve got down in the dirt with them, and if they didn’t give as well as they took I’d tell them they were insults to their upbringing, and I’ve cleared out their lockers for them and piled their clothes out in the hall, thinking I’d make them prove what they had in their veins, blood or spot, one way or the other, and praying they would come through.

Well, you never know. When I was at Alabama I quit one time, and Coach Hank Crisp went to where I was staying and brought me back.

14. The Best Issue: The Legend of Julio Jones

Story headline: Comically Good

Subhead: Having performed mind-bending athletic feats practically since birth, Falcons receiver Julio Jones has become a legend in his own time. Do you believe in superheroes?

Excerpt (by Ben Baskin): There's a story I need to tell you, but you're probably not going to believe it. It begins in September 1901, when John Burton Foley journeyed from the Midwest to Washington, D.C., to attend the funeral of President William McKinley. During those travels a man approached Foley and spoke of an uninhabited land just a few miles from the Gulf of Mexico. Eventually Foley purchased some 50,000 of those acres, harboring visions of the next grand metropolis. But his dream never came to pass. Today, that land in South Baldwin County, Ala., consists mainly of large swaths of farmland dotted with modest residences. Horses and goats graze. Signs with images of tractors and the message share the road line dirt paths.

Foley never would have imagined that long after he bought those 31 square miles, a child with long arms and long legs and big ears would be born there, a child who would later be compared to a beast, a monster, an alien, a legend, a superhero. That out of this dust bowl of obscurity, a man would rise whose life seemed more myth than reality. So if I were to tell you the story of that boy from Foley, and if you closed your eyes, it might feel as if his tale were playing out on black-and-white 8mm film, flickering across a projector screen at 16 frames per second. The tales would seem tall, the details implausible. But after you hear so many witnesses recount so many fantastical stories, you just might find yourself convinced that his legend was true all along.

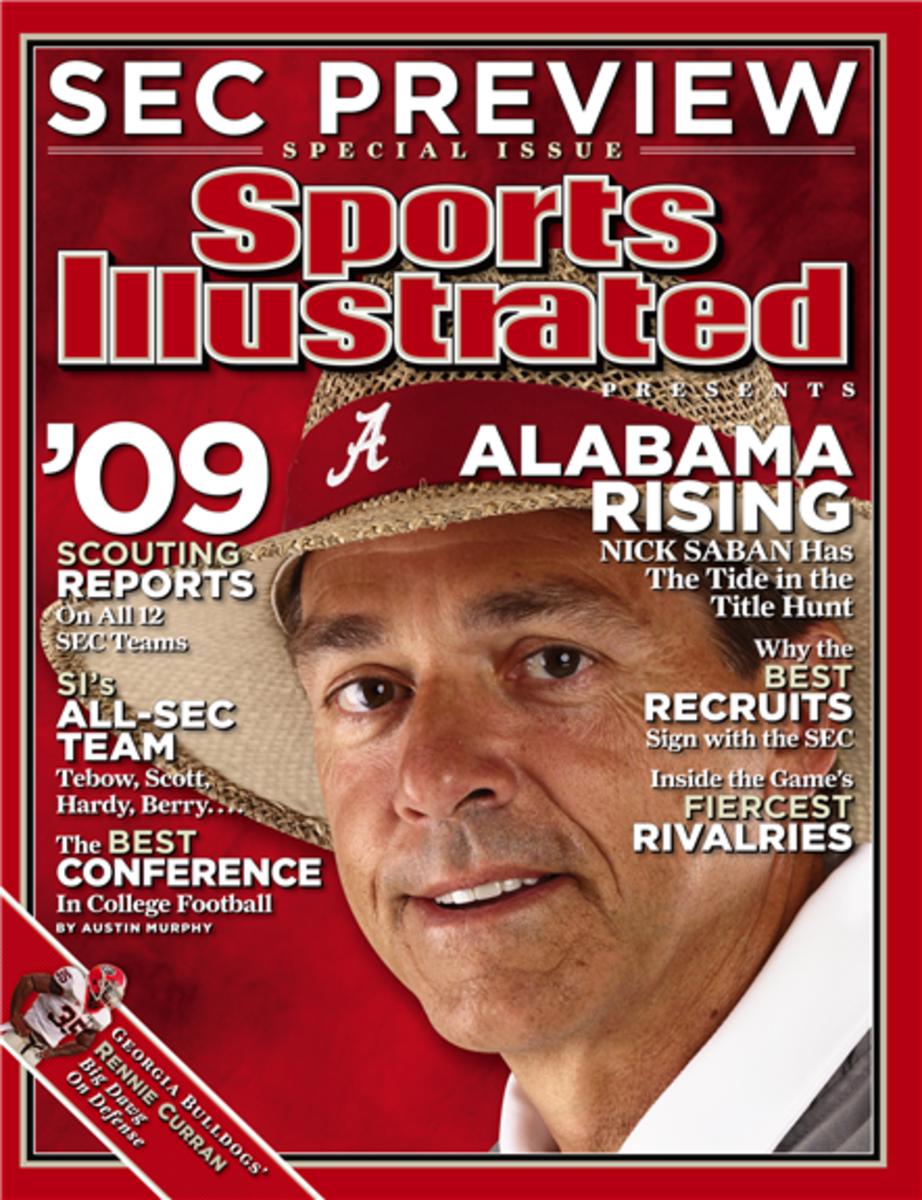

15. 2009 SEC Season Preview (Nick Saban)

Story headline: Alabama Rising

Subhead: Nick Saban has the Tide in the title hunt

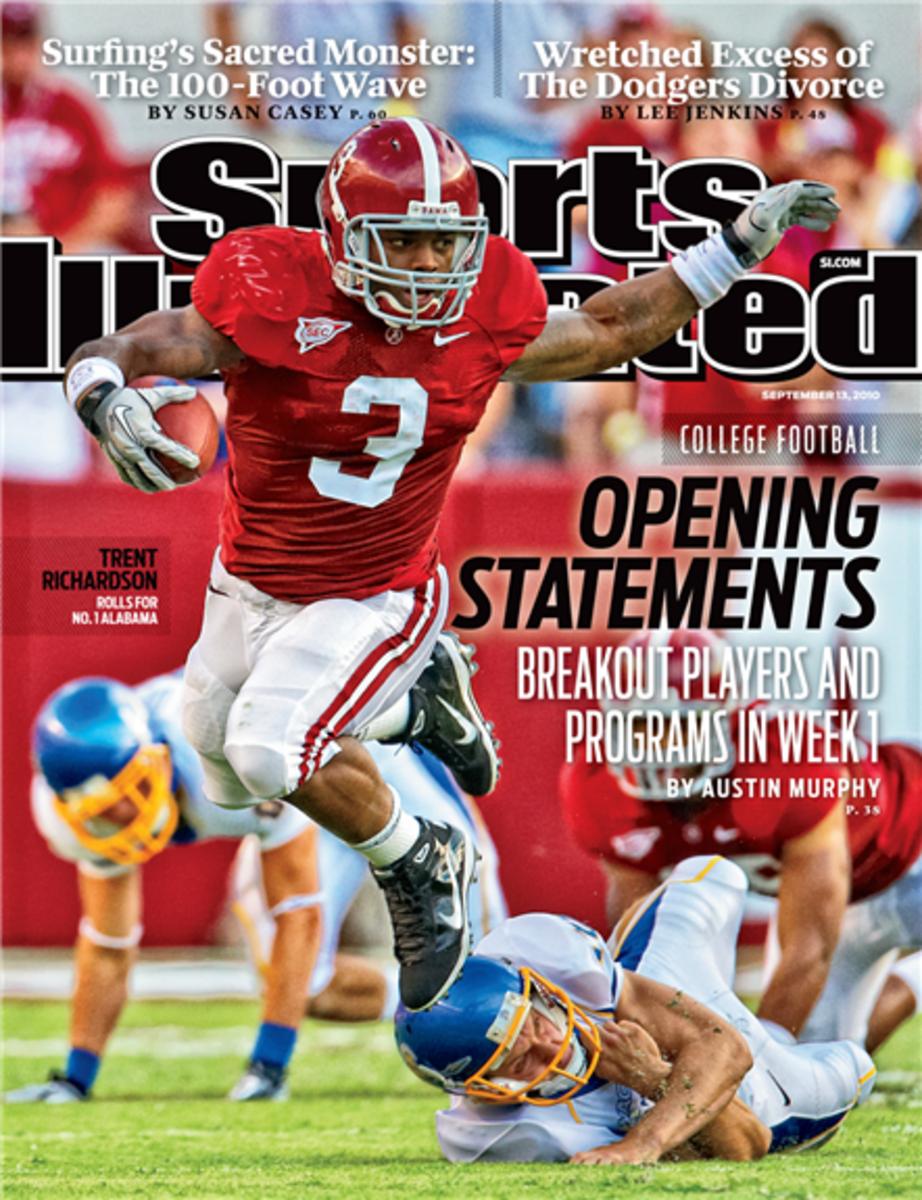

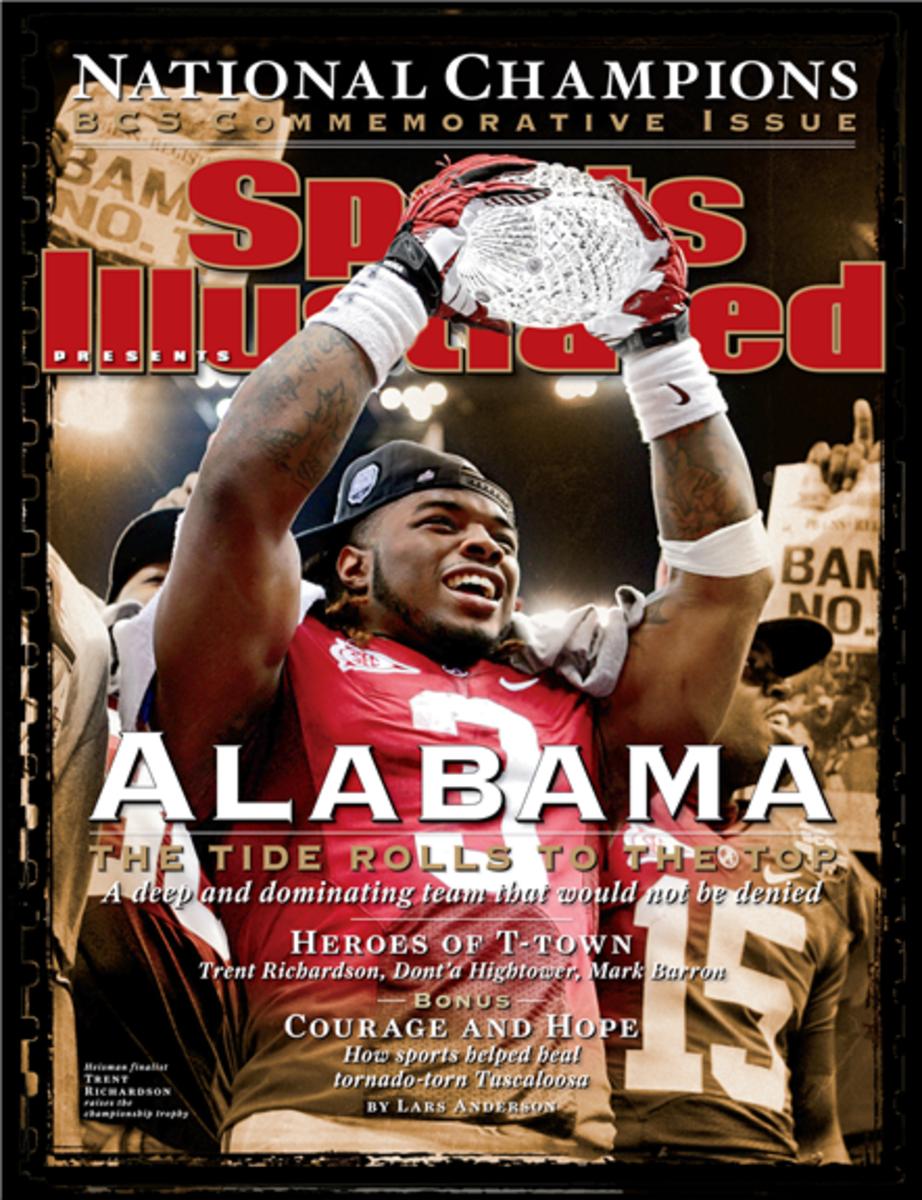

16. Opening Statements (Trent Richardson)

Story headline: In With the New

Subhead: Tim Tebow is a pro, and so is a Texan named McCoy. The college football season kicked off last week minus many familiar names, but in their place emerged several fresh faces who are ready for their close-ups

Excerpt (by Austin Murphy): Top-ranked Alabama, likewise, is loaded at that position, and remains so even after the Tide's biggest scare. In a practice five days before the season opener, Ingram tried to turn the corner on a sweep. Spun around by a defender, the reigning Heisman winner suffered slight cartilage damage in his left knee. Ingram was in surgery the following morning. While the junior was definitely out for 'Bama's opener, Saban would not foreclose the possibility that he might return for Penn State.

"When Mark went down, I was shocked," says Richardson. "I was sad for him. But I still have to go out there and play the football I know how to play."

If he lost any sleep over Ingram's absence, he was probably in the minority in 'Bama Nation. The truth is that no team in the country, with the possible exception of the Carolina Panthers, is better equipped to withstand the loss of its feature back. Notwithstanding Ingram's possession of a certain 25-pound bronze doorstop, there's not a lot of drop-off from him to Richardson, an impossibly buff, 5'11" 220-pounder out of Pensacola, Fla.

"Great player, great person," Jimmy Nichols reminisced last week. Nichols coached Richardson at Escambia High, which happens to be the alma mater of Emmitt Smith. "Emmitt had the ability to run over you or run away from you," says Nichols, "and Trent has those same abilities." In truth, the coach adds, "There's not many I put in [Smith's] class, but Trent's one of 'em. He's bigger, faster and stronger than Emmitt."

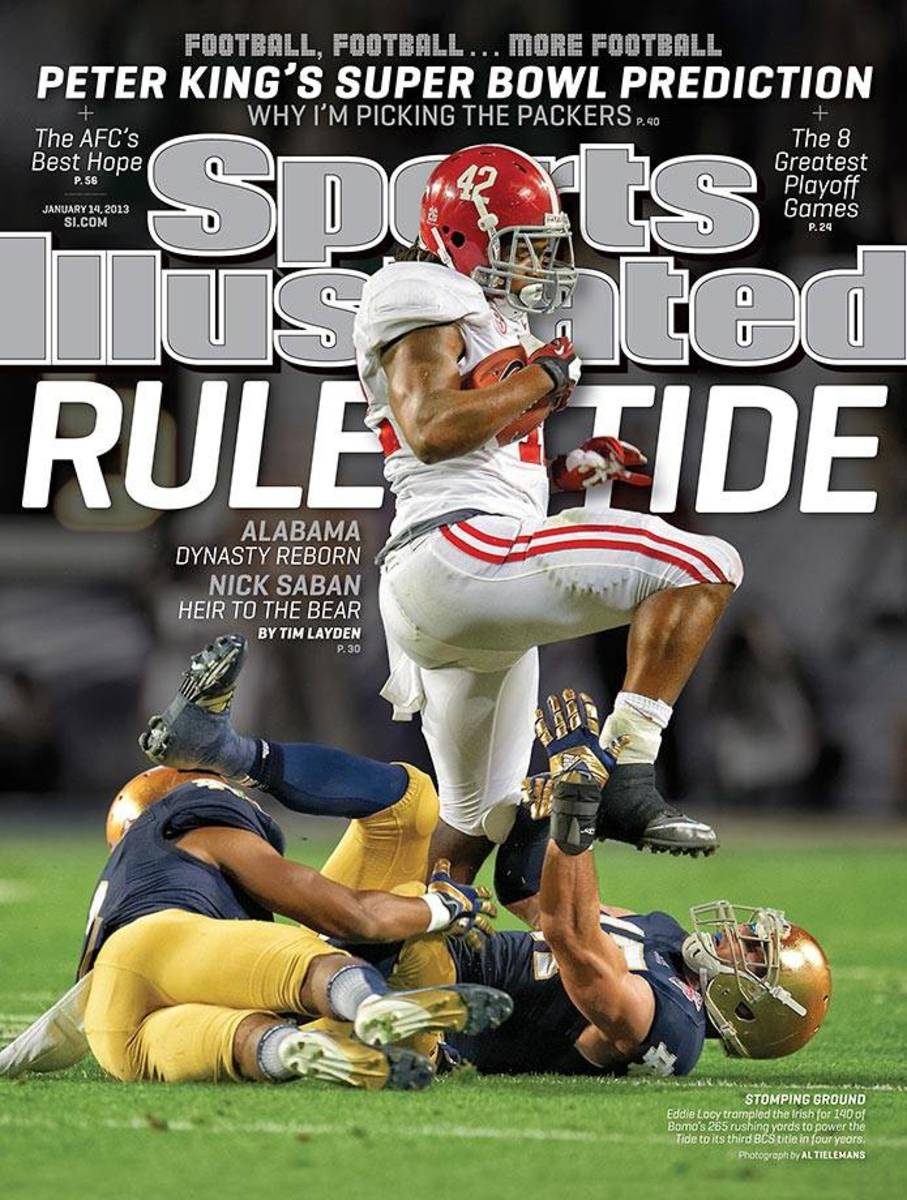

17. Rule Tide (Eddie Lacy)

Story headline: Heir Force

Subhead: Alabama turned what was supposed to be a defensive showdown into an offensive beatdown, and by the second half the only competition remaining was between the school's old coach and it's current one

Excerpt (by Tim Layden): Great things can happen in a place like Tuscaloosa, Ala., where past glory is served with every meal and there is an eternal belief, even during the most uncertain times, that each autumn will bring rebirth. It takes the right coach. It takes the right time.

So it was on Monday night, in a professional football stadium on a lonely tract of land hard by the endless highways of South Florida that Alabama, under coach Nick Saban, returned indelibly not just to the national championship, but also to a place high above the sport itself. The Crimson Tide punished top-ranked Notre Dame 42--14, turning one of college football's most anticipated title games into a punch line, and sending once-euphoric Fighting Irish fans who had sought completion of their own renaissance, walking, humbled, into the tropical darkness.

The championship was Alabama's third in four years, the first such run since Nebraska in 1994, '95 and '97 (the third of which was shared by Michigan). "There's a Sports Illustrated cover hanging in my room — because I'm on it — from 2010," said Alabama senior center Barrett Jones after the game, as "Sweet Home Alabama" filled the air. "It says, 'Dynasty. Can Anyone Stop Alabama?' I'll never forget looking at that thing and wondering if we really could be a dynasty. Three out of four. I'm no dynasty expert, but that seems like a dynasty to me."

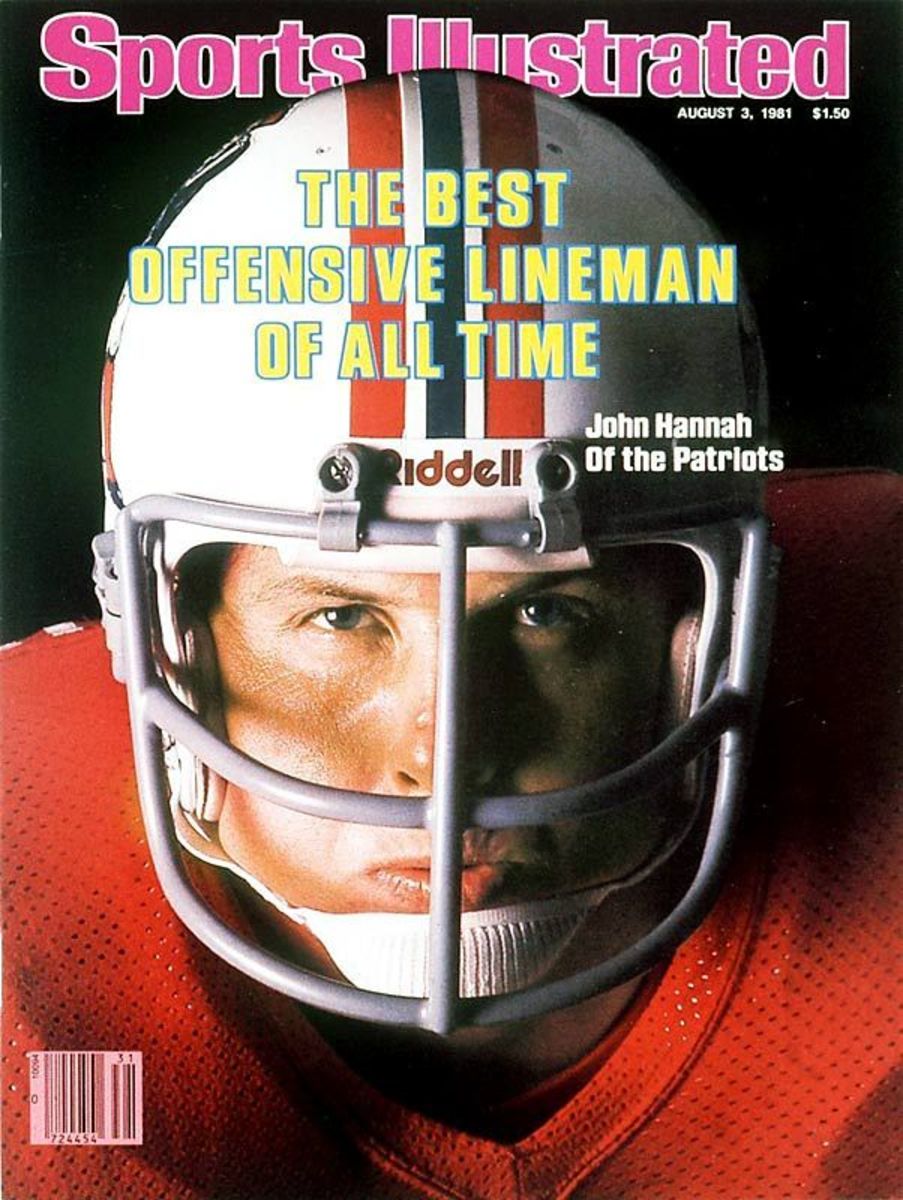

18. The Best Offensive Lineman of All Time (John Hannah)

Story headline: John Hannah Doesn't Fiddle Around

Subhead: At least not on the football field, where, says the author, his brains, brawn and speed have made him the top offensive lineman in NFL history

Excerpt (by Paul Zimmerman): It starts with the firepower, with Hannah's legs, incredibly massive chunks of concrete. "Once we measured John's thighs, and they were 33 inches," says Hannah's wife, Page, a slim ash blonde. "I said, 'I can't bear it. They're bigger than my bust.' "

The ability to explode into an opponent and drive him five yards back was what first attracted the college recruiters to Albertville, Ala., where Hannah grew up and played his final year of high school ball. It's the first thing you look for, if you're building a running game. Hannah says he always had that ability, but it was his first coach at Baylor School for Boys in Chattanooga, a tough, wiry, prematurely gray World War II veteran named Major Luke Worsham, who taught him how to zero in on a target, to aim for the numbers with his helmet, to keep his eyes open and his tail low. Next came the quick feet. Forget about pass blocking if you can't dance. Worsham helped there, too.

"Oddly enough," Hannah says, "he helped me develop agility and reactions by putting me on defense in a four-on-one drill. You'd work against a whole side of an offensive line. It was the most terrible thing in the world. If the guard blocked down you knew you'd better close the gap and lower your shoulder. If the end came down and the guard came out, buddy, you grabbed dirt because you knew a trap was coming."

"For all his size and explosiveness and straight-ahead speed," Kilroy says, "John has something none of the others ever had, and that's phenomenal, repeat, phenomenal lateral agility and balance, the same as defensive backs. You'll watch his man stunt around the opposite end, and John will just stay with him. He'll slide along like a toe dancer, a tippy-toe. And that's a 270-pound man doing that, a guy capable of positively annihilating an opponent playing him straight up."

19. King Crimson (AJ McCarron)

Story headline: Underrated

Subhead: Alabama royalty with a celebrity sweetheart, AJ McCarron arrived in Tuscaloosa as a gunslinger with a hard-scrabble past and an unknown future. Now he's a master of passing efficiency guiding the Tide toward an unprecedented third straight BCS title — and trying to get his due while closing out a career for the ages.

Excerpt (by L. Jon Wetheim): In Birmingham, it's been said, they love the governor. But throughout Alabama an even deeper level of affection is reserved for the quarterback of the Crimson Tide football team.

He is the keeper of a statewide public trust. He is the BMOC of a campus that spans 67 counties. He is the latest in a lineage as indelible as the Tudors or Habsburgs. "You're the quarterback of Alabama and, boy, you know what you're representing," says Joe from the House of Namath, emitting that familiar cackle. "Every day and everywhere you go, you feel the weight of the history and the tradition."

Even so, there are varying levels of endearment. It helps, for instance, when the quarterback is a native of the state—the kind of kid who pronounces Birmingham as Bumminghum, knows the best terrain for four-wheeling and eats at out-of-the-way barbecue joints. "You grow up in Alabama, and the fans feel this extra connection to you," says Jay Barker, earl of Trussville and QB of the 1992 national championship team, now a Bumminghum sports radio host. "For the player, you feel like the ball is in your hands—in every sense."

The fondness for the Bama quarterback grows still more intense when he displays a certain personality—a leader who's also a rebel, the good guy with an edge. Yet love can turn to scorn quicker than you can say Andrew Zow if the Tide doesn't roll. "We had a losing season my junior year, and there was all this talk of how we needed to be rebuilding in the spring," says Namath. "You see, we went 9--2."

All of which is to say, the current king might be more beloved than any of his forebears. Per the tattoo on his chest, senior Raymond Anthony McCarron—nicknamed Ya-Ya, later amended to AJ—is a BAMA BOY.

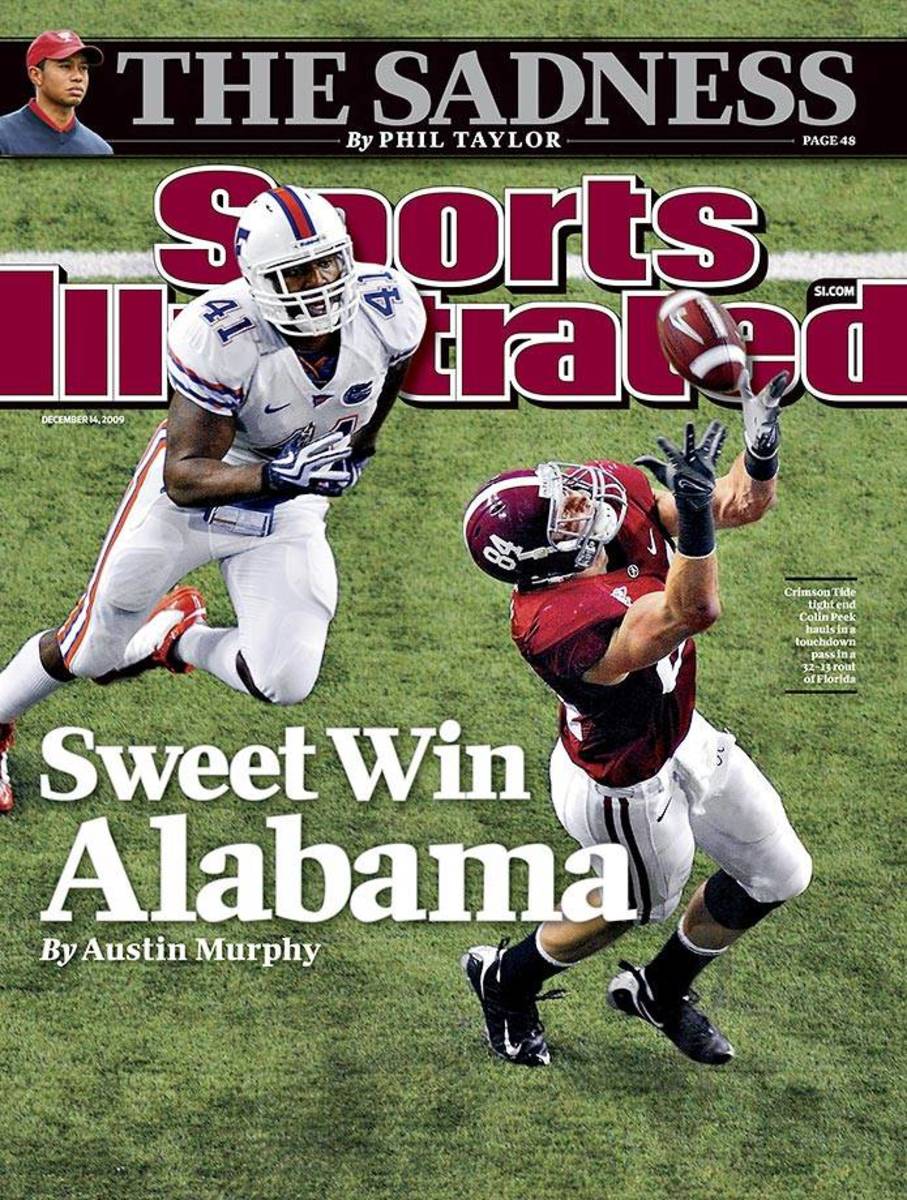

20. Sweet Win Alabama (Colin Peek)

Story headline: Move Over, Gators

Subhead: The new king of the SEC is Alabama, which pushed around Florida on both sides of the ball and moved closer to its first national championship since 1992

Excerpt (by Austin Murphy): If you think it was unsporting and cruel for Alabama fans to cheer the sight of Tim Tebow's tears in the final minute of last Saturday's SEC title game, Terrence Cody asks for your understanding:

"We hear a lot about him being one of the most dominant players ever in college football," explained Cody, the Crimson Tide's terrific nose tackle. "We hear that all the time. For us to dominate him and do all that stuff to him, it meant a lot to us."

It meant more, if possible, to the houndstooth-rocking legions of Alabama faithful, a group of partisans whose pride in their program is matched only by their sense of entitlement. Yes, the Tide had won 21 SEC championships, but the most recent of those came a decade ago. True, 'Bama owns a dozen national championships, but the Tide has been stuck on that number for 17 years. By reducing Tebow to tears and otherwise bullying the defending national champions in a 32-13 drubbing in the Georgia Dome, Nick Saban's squad earned a spot in the BCS title game, to be played on Jan. 7 in the Rose Bowl. There Alabama will be favored over a Texas team sure to run out of the tunnel in a foul mood—a by-product of the month of abuse the Longhorns must now endure following their coyote-ugly victory over Nebraska in the Big 12 title game later on Saturday.

This was the long-awaited evening that would dispel the fog, clarifying the BCS landscape and bringing the Heisman picture into focus.

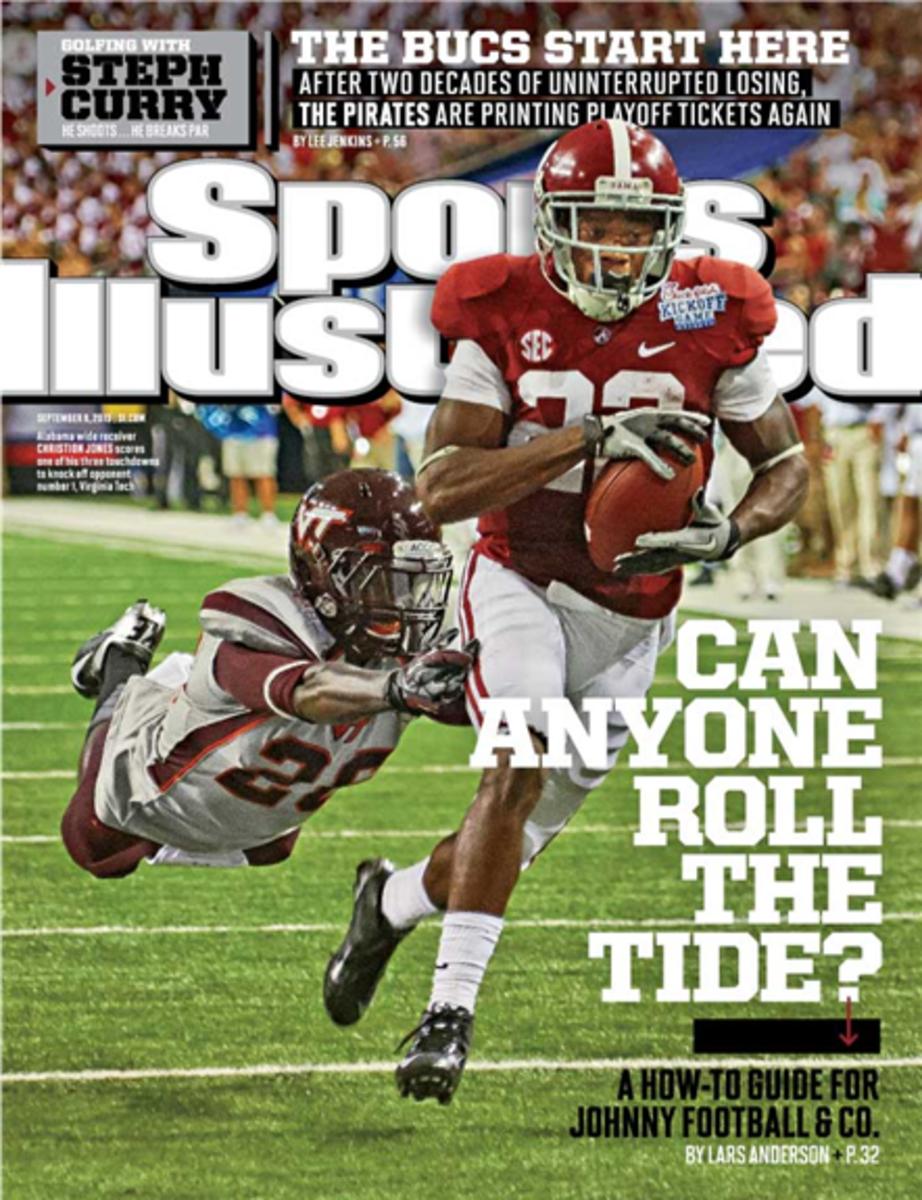

21. Can Anyone Roll the Tide? (Christion Jones)

Story headline: How to Beat Bama

Subhead: The Crimson Tide [is] expertly coached, stacked with future NFL talent and confident of running the table, but opponents who are smart, willing and armed with the right personnel can take eight simple steps and make one giant leap past the bullies of the BCS. And the team that did just that in 2012 is up next.

Excerpt (by Lars Anderson): College football is a game of mercurial bounces, tip-of-the-finger deflections and freak injuries, and it requires good fortune as much as good fundamentals to navigate through a season undefeated. Just ask Kansas State, the reigning Big 12 champ, which lost 24-21 at home last Friday night to a big-hearted team from the backwaters of the Football Championship Subdivision, North Dakota State. The sport is riveting not just because Davids can beat Goliaths, but also because that one loss can crushed a title contender's hopes—even if that contender is littered with five-star recruits on its third string.

Which brings us to the question that hangs over the nation as the 2013 season gets under way: Can anyone take down No. 1 Alabama?

The Crimson Tide's opener last Saturday no doubt emboldened those who say yes.

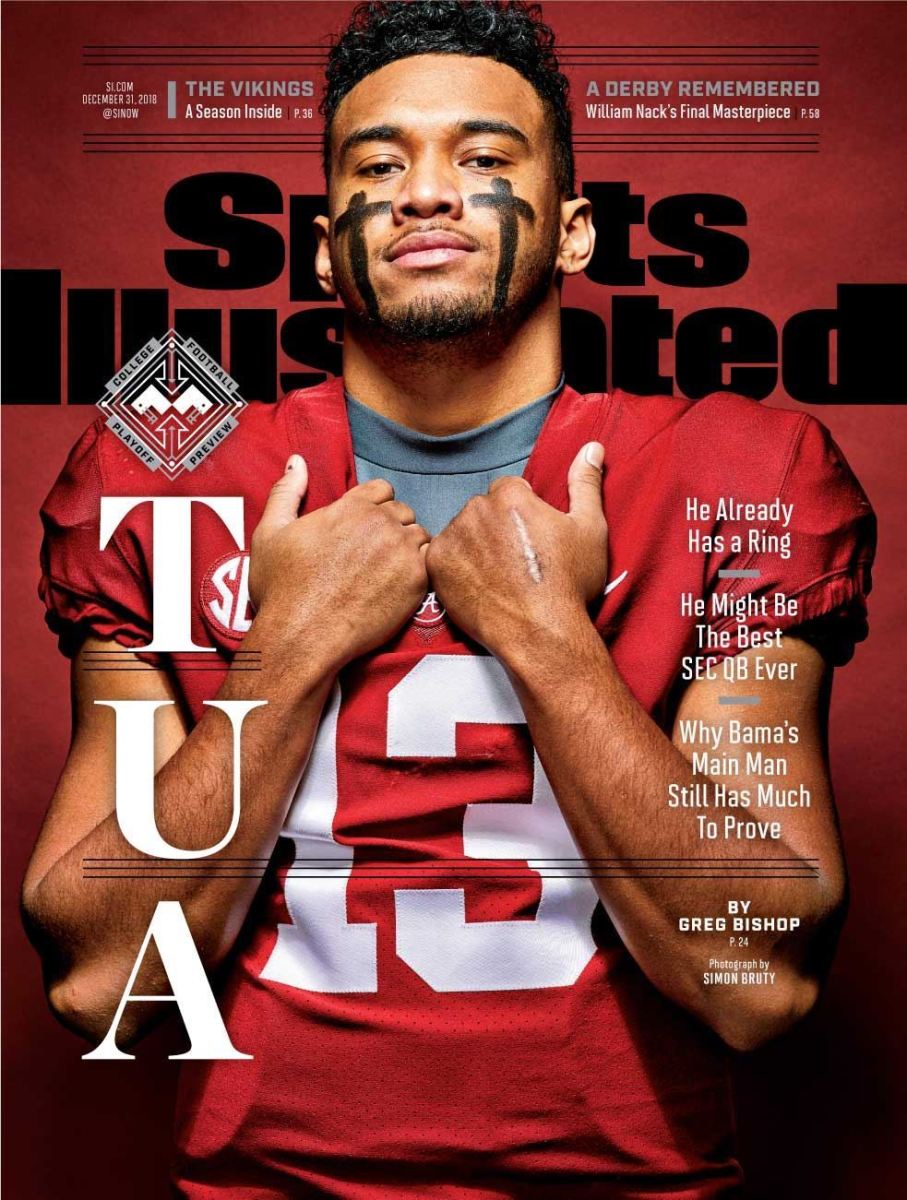

22. Tua

Story headline: Take Tua

Subhead: A year later, at the scene of his biggest triumph, Alabama quarterback Tua Tagovailoa was humbled and hurt. Now the sophomore must recapture the magic he found during a brilliant regular season, not only to win a second straight College Football Playoff but also to represent proudly his family and his heritage

Excerpt (by Greg Bishop): The dreams started coming to Seu Tagovailoa almost 20 years ago, these visions that unveiled the prophecy of a boy whose greatness would be revealed on the football field. Seu would prop his infant grandson on one knee and tell the child known as Tua, "Your name is everything. And one day, it will be known all over the world."

Seu had moved from American Samoa to Hawaii years earlier in search of more opportunities for his six daughters and three sons. He left behind his status in the village and his job as a police officer and became a hotel security guard and the head deacon at their small family church in working class Ewa Beach on the island of Oahu. He prayed every day and ministered every weekend, ferrying the young children in his small car, making the rest of his family take the bus.

More than anything, Tua's grandfather sought to influence future generations of Tagovailoas by sowing fearlessness in their souls. He would tell them that they were lions, strong and daring and capable of transforming sheep into mighty warriors. This was Tua's destiny, of that Seu was certain, and if the prophecy of his oldest grandson seemed to border on delusion or hyperbole, he assured Tua that if he did only what was asked of him, the nonbelievers would know his name in time. "My father saw in Tua something the world is just starting to see now," says his aunt, Sai Amosa. "That he's playing for God and playing for the universe. An audience of one and an audience of all."

23. 2011 commemorative edition

Story headline: Total control

Subhead: With its suffocating defense and surprisingly strong passing game, the Crimson Tide mastered LSU, leaving no doubt about who was No. 1

Excerpt (by Austin Murphy): Tony McCarron was asleep in his dorm room at Station No. 11 in Mobile when his phone went off around midnight on Nov. 7. It wasn't an emergency. It was an epiphany. McCarron is a fireman; his eldest son, AJ, is the starting quarterback at Alabama. AJ was calling a little more than 24 hours after the Tide's 9-6 overtime loss to LSU. "I could tell he was shook-up," recalls Tony. While AJ's numbers in that game were decent—he completed 16 of 28 passes for 199 yards, with an interception—he was quick to don a hair shirt after the game, beating himself up for playing with excessive caution. The moment had called for a daredevil, and he'd channeled his inner actuary.

"He felt as if he'd let his teammates down," Tony recalls, "and he was torn up about it." AJ made this vow to his old man: "Daddy, I will never play another game where I allow the other team to dictate how I play. I was so worried about losing the game for my team, I didn't go out and win it."

True to his word, and to the surprise and delight of an Alabama fan base that had seldom, if ever, seen such a virtuoso performance by a quarterback in a national championship game, the redshirt sophomore flat out shredded LSU's defense in their BCS title match in New Orleans on Monday night. The only thing more remarkable than McCarron's line in 'Bama's methodical 21-0 dismantling of the top-ranked Tigers—he completed 23 of 34 passes for 234 yards—was the fact that, finally, after seven-plus quarters of play this season, one of these teams finally carried the football into that rectangle known as the end zone.

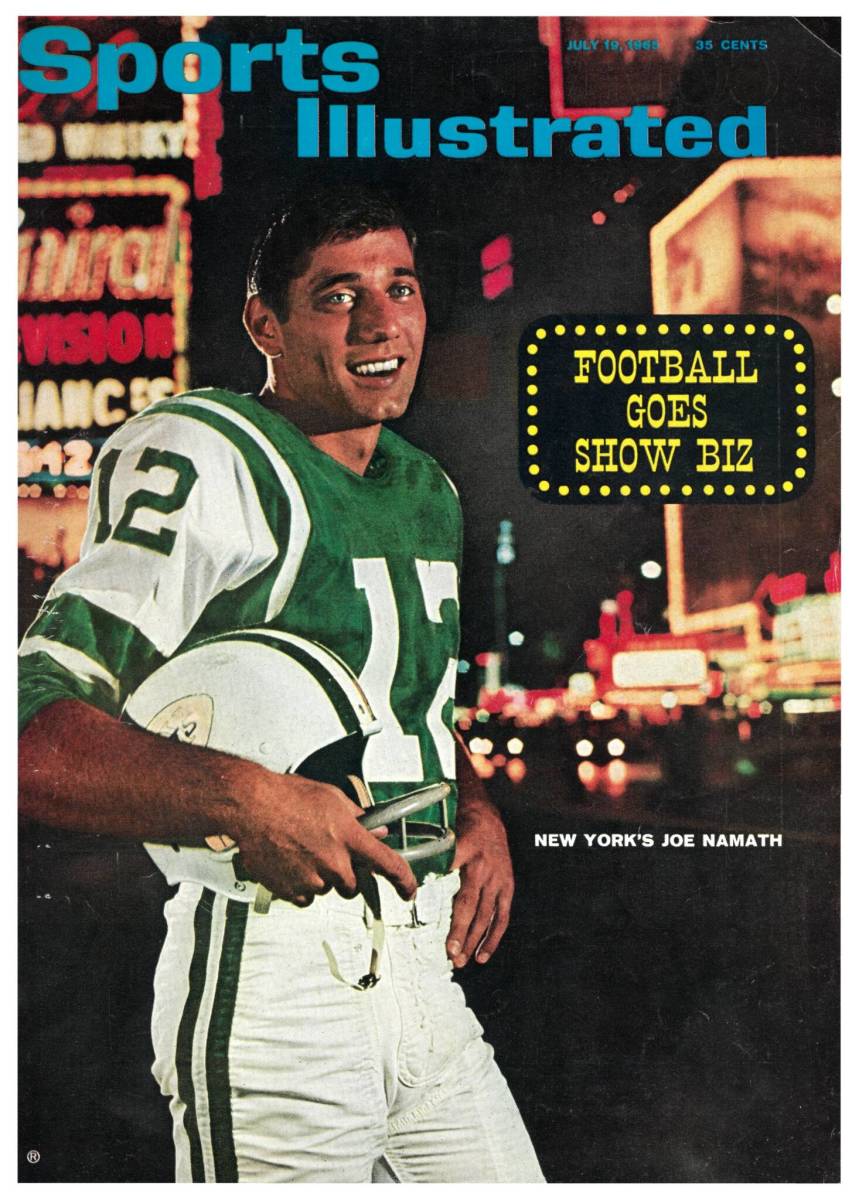

24. Broadway Joe

Story headline: Show-Biz Sonny and his Quest for Stars

Subhead: Sonny Werblin of the Jets and his two rookie quarterbacks, Joe Namath and John Huarte, form pro football's most interesting triangle

Excerpt (by Robert H. Boyle): This week, in the quaint Hudson River town of Peekskill, N.Y. the New York Jets of the American Football League open training with 28 rookies who cost a total of $1.1 million to sign, the most money ever committed for new talent in one year by any pro football team. Among the rookies coming on strong are Cosmo Iacavazzi, Princeton's All-America fullback; Verlon Biggs, mammoth defensive end from Jackson State; Bob Schweickert, All-America back from VPI; Jim Harris, a gigantic lineman from Utah State; George Sauer, the dropout flanker from Texas; and, finally, to the blare of trumpets, a roar of welcome from the M-G-M lion and a thumping bong from J. Arthur Rank's gong, the two most publicized college quarterbacks in America: Joe Namath of Alabama, everyone's darling in the pro football draft, and John Huarte of Notre Dame, the Heisman Trophy winner. Namath, who cost the Jets an estimated $400,000, and Huarte, who so far has refused to develop a complex despite signing for only about half as much, will do battle with Mike Taliaferro, a holdover from last season, for the job of No. 1 quarterback. A few years ago, when the Jets were the hapless Titans, most pro football fans could not have told you if the team even had a quarterback, much less his name. Now, thanks to the astute handling and fathomless bankroll of David (Sonny) Werblin, the president of the Jets, the competition for quarterback has achieved all the supercolossal proportions of the casting of Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind. And with good reason: Sonny Werblin wants a star. "I believe in the star system," he says. "It's the only thing that sells tickets. It's what you put on the stage or playing field that draws people."

As a result of the brouhaha aroused by the signing of Namath and Huarte, the Jets have sold the improbable number of 35,000 season tickets, as compared to only 11,000 at this time last year, and on this score alone Sonny Werblin has to rank as one of the most clever, fascinating and energetic operators to emerge in sports since Larry MacPhail showed up at Cincinnati's Crosley Field with the Kaiser's ashtray and the idea of night baseball.

No one knows better than Werblin the value of a star.

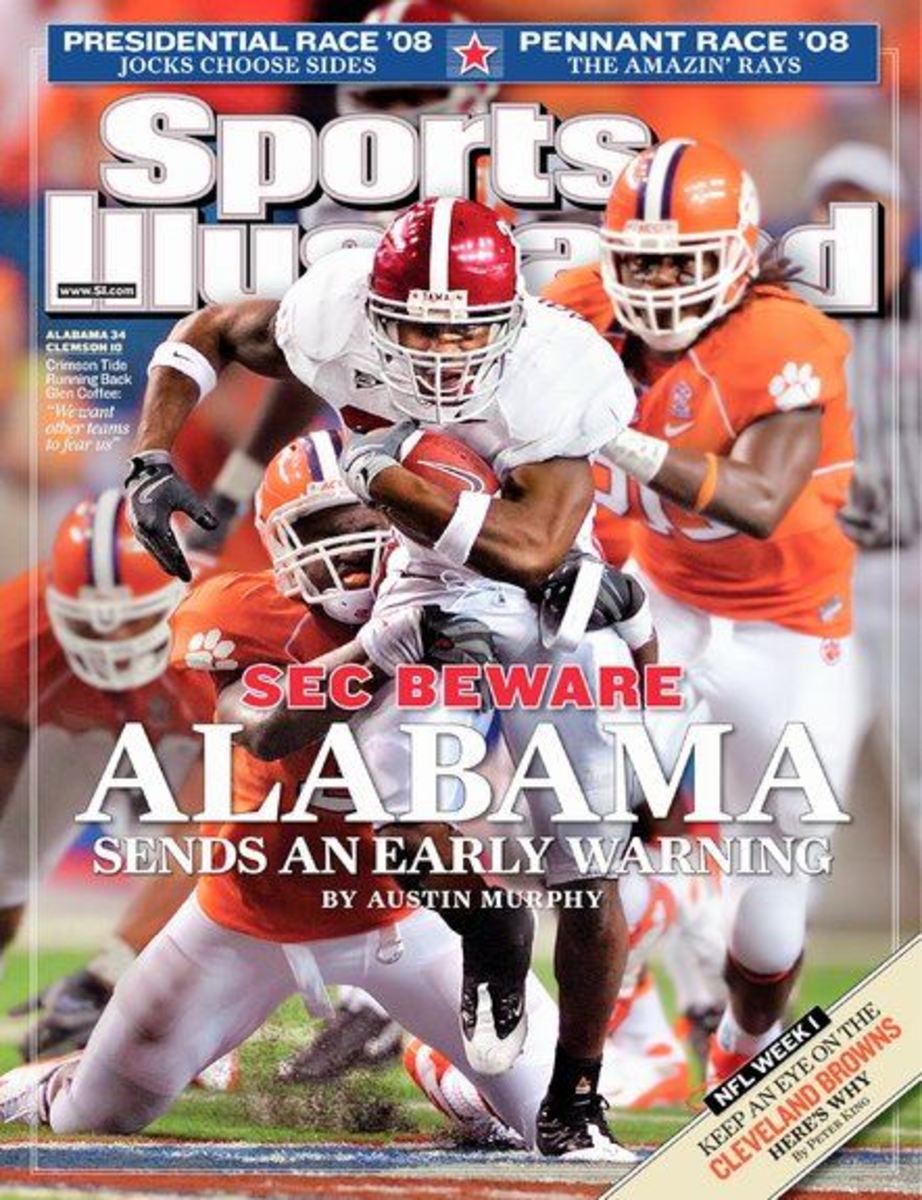

25. Alabama Sends an Early Warning (Glen Coffee)

Story headline: The Tide is Turning

Subhead: On an opening weekend that produced a handful of surprises, none was bigger than Alabama's dominance of Clemson

Excerpt (by Austin Murphy): He is this intriguing blend of New Age and Old School. But with kickoff against ninth-ranked Clemson looming last Saturday night in the Georgia Dome, Nick Saban dispensed with the psychobabble and channeled the Bear. "If we're going to win this game," Alabama's glowering second-year coach told his charges, "our defensive line is going to have to whip their offensive line."

Having issued that challenge, the man with the perma-tan watched his D-line, anchored by SUV-sized nose guard Terrence Cody, rise to it. While it was the Tigers who came into this Chick-fil-A College Kickoff with arguably the nation's top tailback tandem in James Davis and C.J. Spiller, 'Bama outrushed Clemson, 239 yards to ... zero.

"Doesn'tmatter how good they are," noted Crimson Tide linebacker Brandon (Knock You on Yo') Fanney, "if they got no hole to go through."

The 34-10 score barely hints at Alabama's soup-to-nuts domination of a squad thought to be the class of the ACC. It is also an indication that Saban has this storied program on track to return to the grandeur that many of its fans still consider their birthright.

Honorable menions

Consider this the college football poll equivalent to receiving votes ...

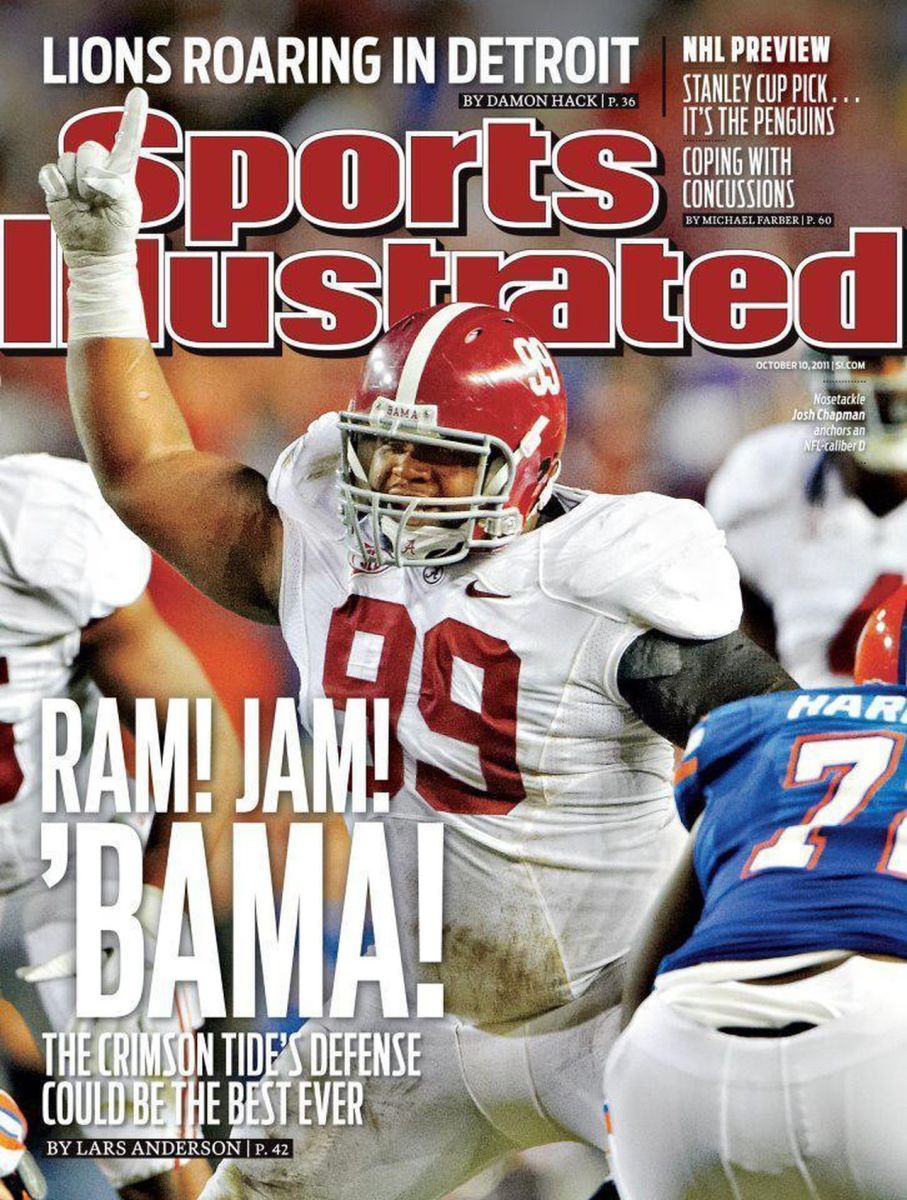

Ram! Jam! Bama! (Josh Chapman)

Story headline: Tide and Punishment

Subhead: As Florida now painfully knows, Alabama has the best defense in the nation. It's also one of the best ever

Excerpt (by Lars Anderson): The 2011 Tide D made an arresting case in the second half of its 38-10 drubbing of No. 12 Florida, which entered the game leading the SEC in total offense (461.8 yards per game). After senior inside linebacker Courtney Upshaw knocked Brantley out of the game with a lower right-leg injury on a brutal sack late in the second quarter, 'Bama made a few critical halftime adjustments—a Saban signature—such as switching to more zone coverage to counteract the Gators' crossing pick routes. Florida's production after intermission: zero points, two first downs, 32 rushing yards and 46 total yards. Combine that sort of unmerciful defensive performance with a potent power-rushing game (junior Trent Richardson ran for a career-high 181 yards), and it's easy to understand the national-title buzz in Tuscaloosa.

"We thought we could run the ball efficiently, but Alabama tackles really well," said Gators running back Jeff Demps, who was held to four yards on three carries a week after rushing for 157 yards against Kentucky. Added Rainey, who entered the game averaging 102.8 yards and 6.5 a carry but finished with a mere four yards on 11 attempts, "Just call it a punch in the mouth."

How spectacularly good has this Tide D—with 10 starters back from last year's unit, which finished fifth nationally—been through five games? Alabama leads the country in scoring defense (8.4 points) and rushing defense (39.6 yards), and also ranks third in total defense (191.6 yards). "We come to punish people," says Upshaw, who had four tackles and an interception, which he returned for a 45-yard touchdown. "But everything we do starts with Coach Saban. Everything."

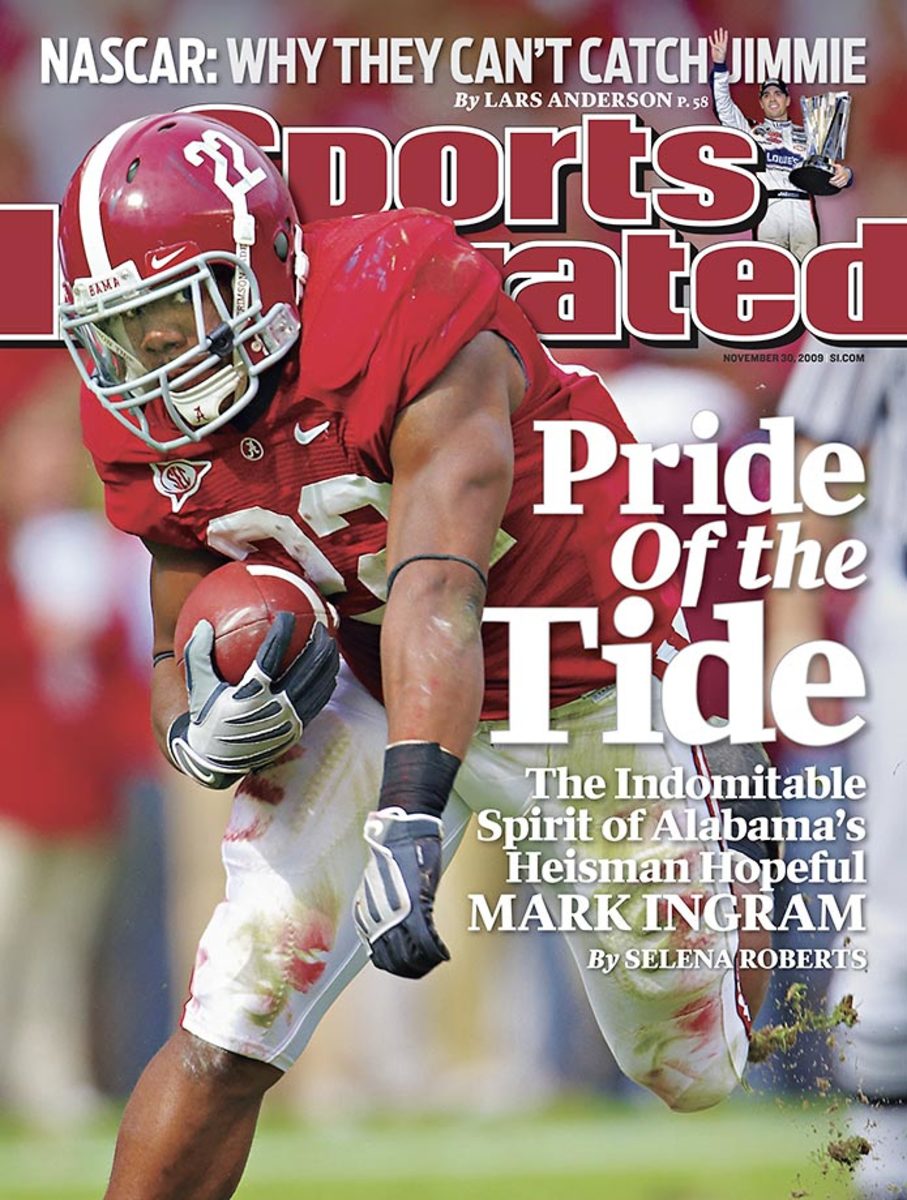

Heisman Hopeful Mark Ingram

Story headline: 'Bama's Backbone

Subhead: As his troubled father watches from prison, Mark Ingram is carrying the Crimson Tide on a national title run and trying to deliver the first Heisman in the program's proud history

Excerpt (by Selena Roberts): His son grew up seeing his father play and, at times, hearing just how high expectations can be. "We'd be in a stadium and the fans would say things, and not always nice things," says Shonda. "I think growing up with that helped Mark mature." Saban sees on a daily basis the evidence of Little Mark's background as the son of a former professional athlete. "He doesn't take coaching as criticism," says Saban. "That's how a professional handles it too."

Mark Jr. could have played any sport—even golf, which was his father's preference—but his love was football. "I run with a purpose," he says. "I love that feeling." The more he played as a high school star, the more his father's pro legacy hung over him. He was always referred to with one title: son of the former NFL player. "I'm proud of my dad," Mark Jr. says. "But now I'm becoming known for what I do, for being myself, and I'm not living in his shadow anymore. I'm carving out my own identity."

He is all at once trying to separate himself from his father the pro while maintaining a tether to his dad's love. Whatever emotional and financial burdens have been freighted on the family due to Big Mark's choices—he has been in legal trouble since 2001, when he was caught with counterfeit cash—those issues remain within the family circle. The Ingrams do not indulge in the Oprah-style public catharses that are so common in a tell-all society. This is how they cope: by trying to live normally. "Mark has had to endure a lot on his way to 20," says Johnson. "It has taken a lot of maturity to get through it, and that's important, but he's also had a lot of help and support. He's a momma's boy. She delivers for him. She's got his head on straight."

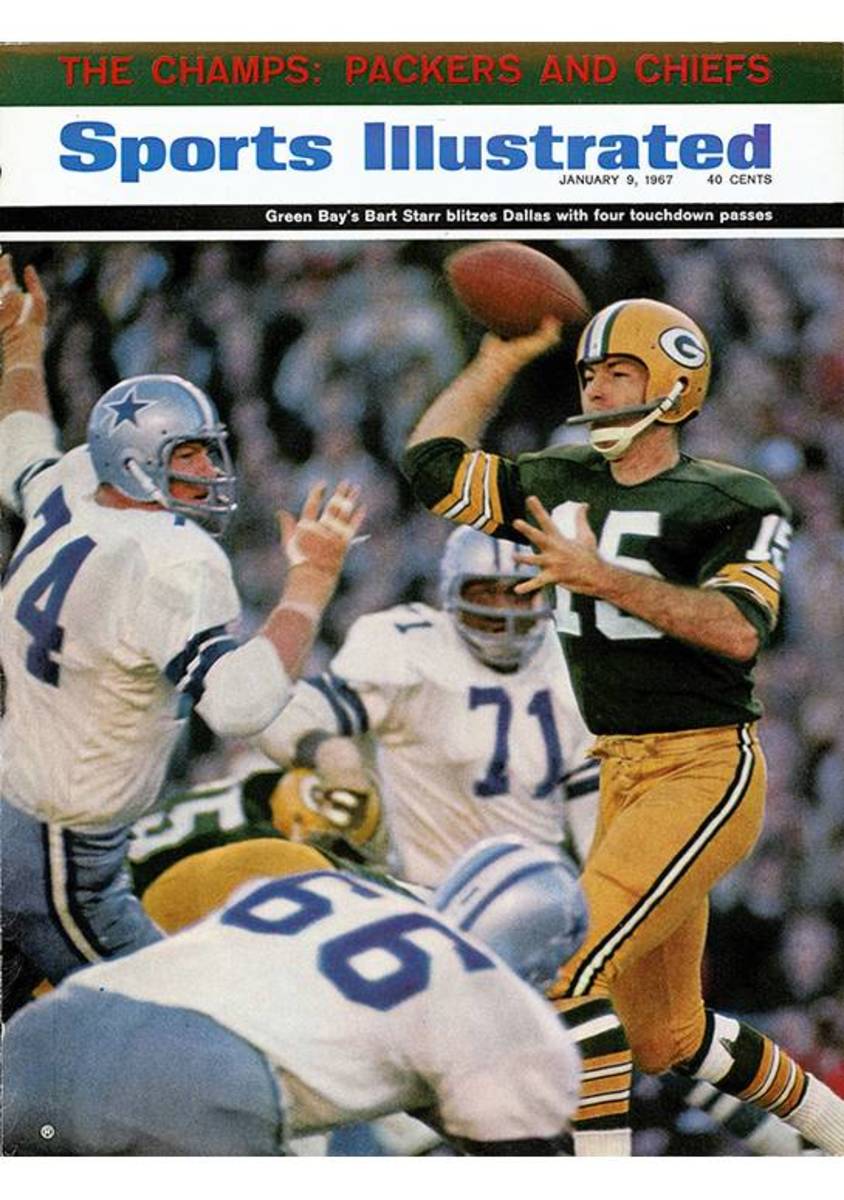

The Champs (Bart Starr)

Story headline: Green Bay Rolls High

Subhead: Cowboy Don Meredith harassed the Packers' defense all day, but a rambling, gambling Bart Starr passed Green Bay to another NFL championship and into the Super Bowl against the Kansas City Chiefs

Excerpt (by Tex Maule): Where Landry used an understated approach in order to settle the nerves of his young Cowboys, Lombardi did just the opposite in order to nettle his veterans into the ferocity he expects from his teams.

He snapped and snarled at them all week long. The last note of levity came in Green Bay just before the departure for Tulsa, when Paul Hornung (who was to spend the entire game Sunday on the bench) broke up the team with a story about Lombardi that reflects the respect and awe with which his players regard him. According to Hornung, when the team returned to Green Bay at 2 o'clock in the morning after their season-ending Los Angeles victory, Lombardi was delayed for an hour or so at the airport in zero weather, signing autographs and talking to well-wishers. By the time he got home he was almost frozen. When he finally got into bed his wife, Marie, shivered and said, "God, your feet are cold." Said Lombardi, sleepily, "In bed you may call me Vincent, dear."

Lombardi laughed as hard as the players at the joke, but once the team arrived at the Camelot Inn in Tulsa he worked them mercilessly.

Fuzzy Thurston, the fine Green Bay guard, said in his oratorical style, "This game will prove for all time, for all history, the greatness of my teammates. This is the big one for all of us. There are players on this team who are near retirement, and none of us wants to retire with a bad taste in his mouth. As the great Johnny Blood once said, 'We professional athletes are very lucky. Unlike most mortals, we are given the privilege of dying twice—once when we retire and again when death takes us.' " Now Thurston, a blocky, square, very tough-looking man, lowered his voice to a sentimental organ tone. "I would like to die happy," he said.

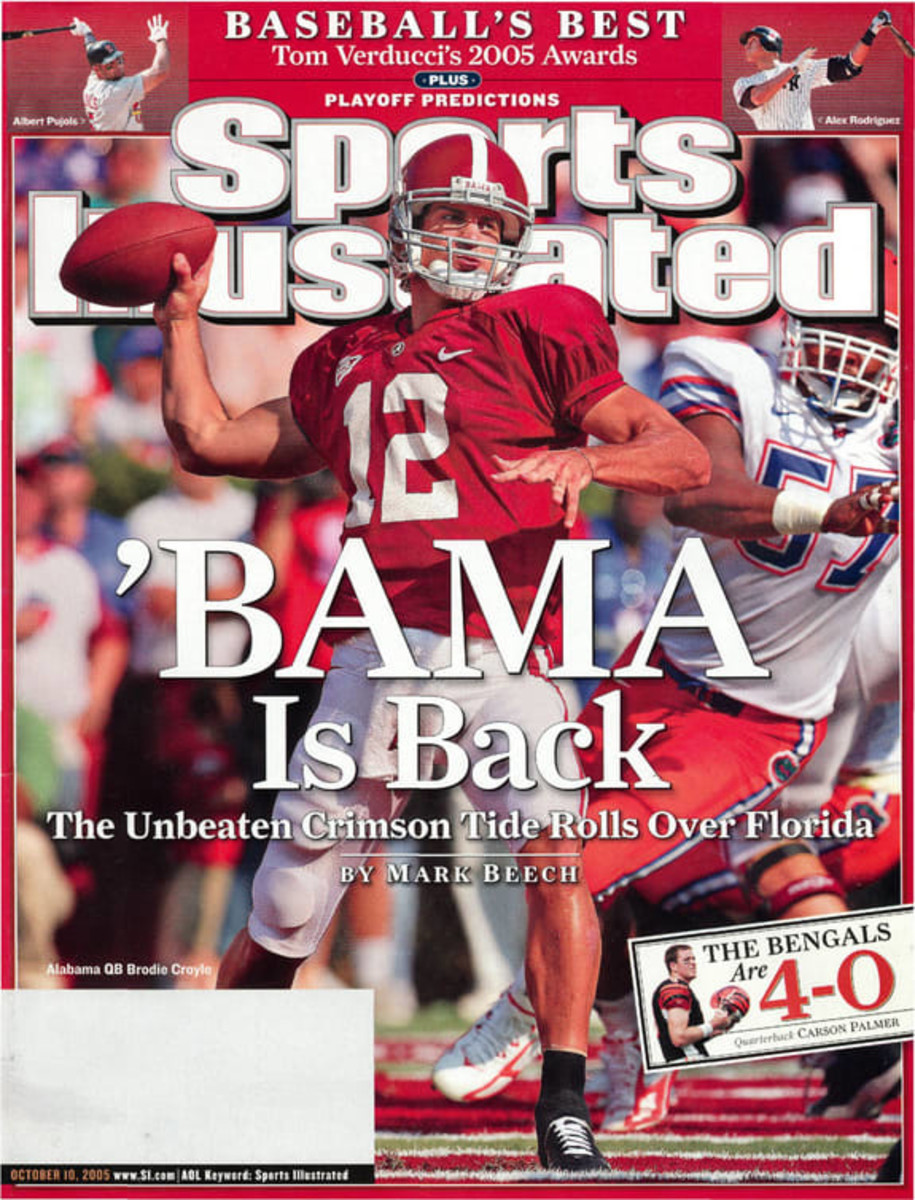

Bama Is Back (Brodie Croyle)

Story headline: The Tide has Turned

Subhead: After a decade of struggles, Alabama is again rolling behind a strong-armed quarterback who wears number 12. Florida found that out the hard way

Excerpt (by Mark Beech): What makes this Alabama team so much fun to watch is that coach Mike Shula finally has an offense to go with his magnificent defense, which ranks sixth in the country after finishing second last season. The difference between this year's Tide and last year's 6-6 team has been Croyle, who missed all but the first three games of 2004 with a torn ACL in his right knee. He was completing 66.7 percent of his passes when he went down in the first series of the second half against Western Carolina, a game that Alabama was leading 31-0. "I knew right away when it happened," Croyle recalls. "With everything I'd been through at Alabama, it was like, When's it going to end?"

Without him, the offense foundered. Backup Spencer Pennington--who left the team after the season to concentrate on baseball--was an inconsistent passer, which forced Shula to rely excessively on the running game. The all-too-predictable attack finished 94th in the country in total offense.

This season Alabama leads the SEC in pass efficiency and ranks fifth in total offense (402.4 yards per game). On Saturday, Croyle connected with six receivers, at points all over the field. "Everything starts with the quarterback," says [offensive coordinator Dave] Rader, "and having Brodie allows us to do a lot of things."

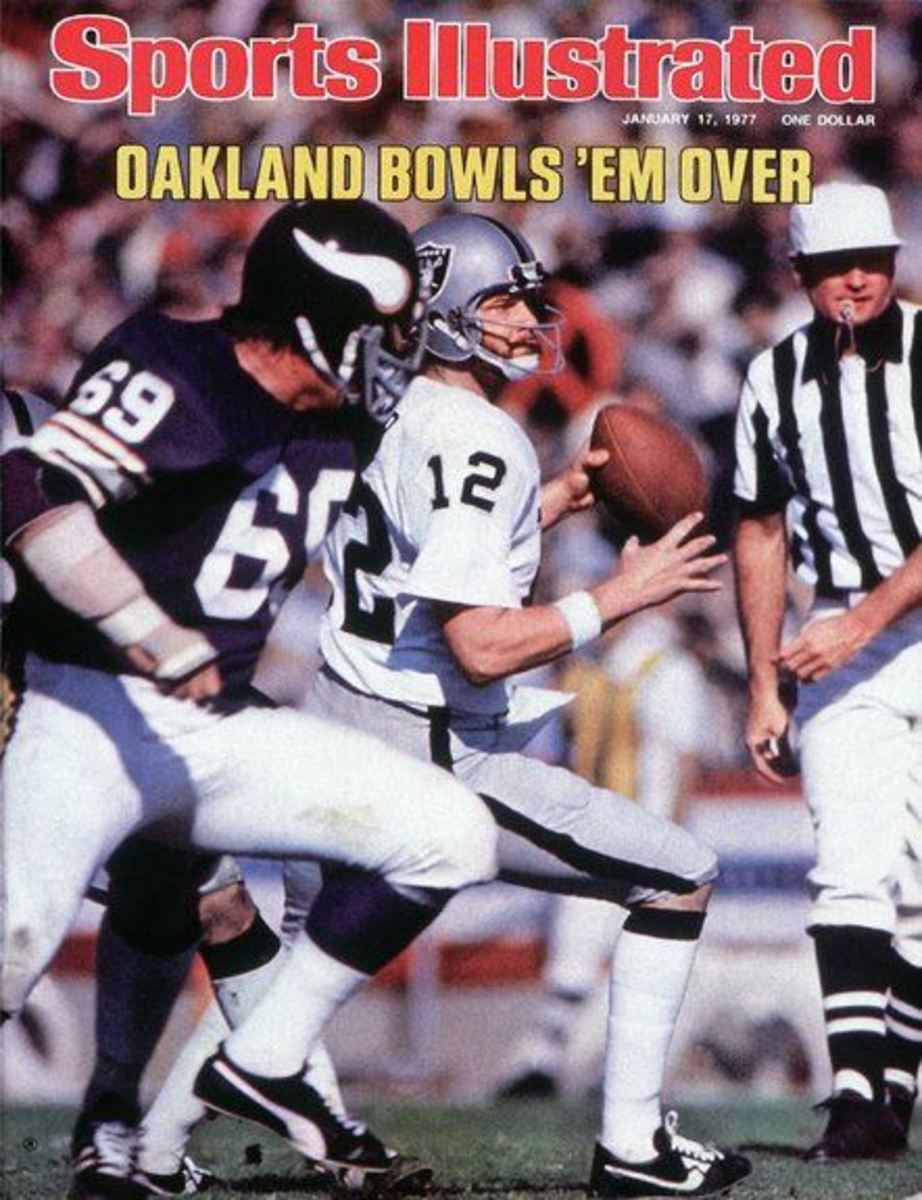

Oakland Bowls Them Over (Kenny Stabler)

Story headline: The Raiders Were All Suped Up

Subhead: And the Vikings were all but wiped out in the Super Bowl, as Oakland ran and passed pretty much as it pleased in setting a record for total offense. But the final score may be of interest only to trivia fans

Excerpt (by Dan Jenkins): For your final halftime stunt, ladies and gentlemen in the stands for Super Bowl XI, write down on your cards what you think of the Minnesota Vikings so far. Now hold the cards up.

Nah, it would never clear the censors. The football game was essentially over by then, as so many Super Bowls have been concluded prematurely by the Vikings, who somehow seem to save their worst for Pete Rozelle's answer to urban strife set to music and pigeons. The only fascinating part was how ingeniously easy Minnesota made it for the Oakland Raiders this time. It was perfectly evident that the Raiders came to play a superb game; it was just that no one realized they wouldn't have to.

Before the final score becomes a question for trivia experts, let it be stated that the bearded, brawling Raiders won the "World Championship Game" 32 to 14 last Sunday afternoon. They did it by lavishing on themselves all kinds of luxuries seldom seen in clashes that are supposed to be close and hard-fought and nervously contested. They played throw-and-catch as if they were in a game of two-below touch. They made a running star out of a former USC halfback who isn't known by his initials. They had a punt blocked for the first time since Ray Guy was in diapers. They missed a field goal and two extra points when Errol Mann kept aiming at the Ventura Freeway instead of the Rose Bowl uprights. They got a 75-yard touchdown dash with an interception out of a fellow who can't outrun anybody but John Madden and Fran Tarkenton. And what it all meant was that these Raiders were so ready and so talented, they succeeded in turning the Super Bowl halftime extravaganza into something people seriously watched.

This, of course, was well after the Vikings had gotten the two big breaks in the early part of the proceedings—a missed Oakland field goal and a blocked Oakland punt—and wound up with a 16-0 halftime score. Oakland's favor. After that it was perfectly clear to the 100,421 Pasadena witnesses that the Vikings were going to do for the Raiders what they had done for the Kansas City Chiefs in the 1970 Super Bowl (they lost 23-7), what they had done for the Miami Dolphins in the 1974 Super Bowl (they lost 24-7), and what they had done for the Pittsburgh Steelers in the 1975 Super Bowl (they lost 16-6).

And when it was over, poor Fran Tarkenton repeated what he had said after two of those wonderful exhibitions: "They played extremely well. We played lousy."

This is the fifth in a series of 25 Top 25 stories, ranking the Crimson Tide nearly every way imaginable.