The Cal 100: No. 20 -- Joe Roth

We count down the top 100 individuals associated with Cal athletics, based on their impact in sports or in the world at large – a wide-open category. See if you agree.

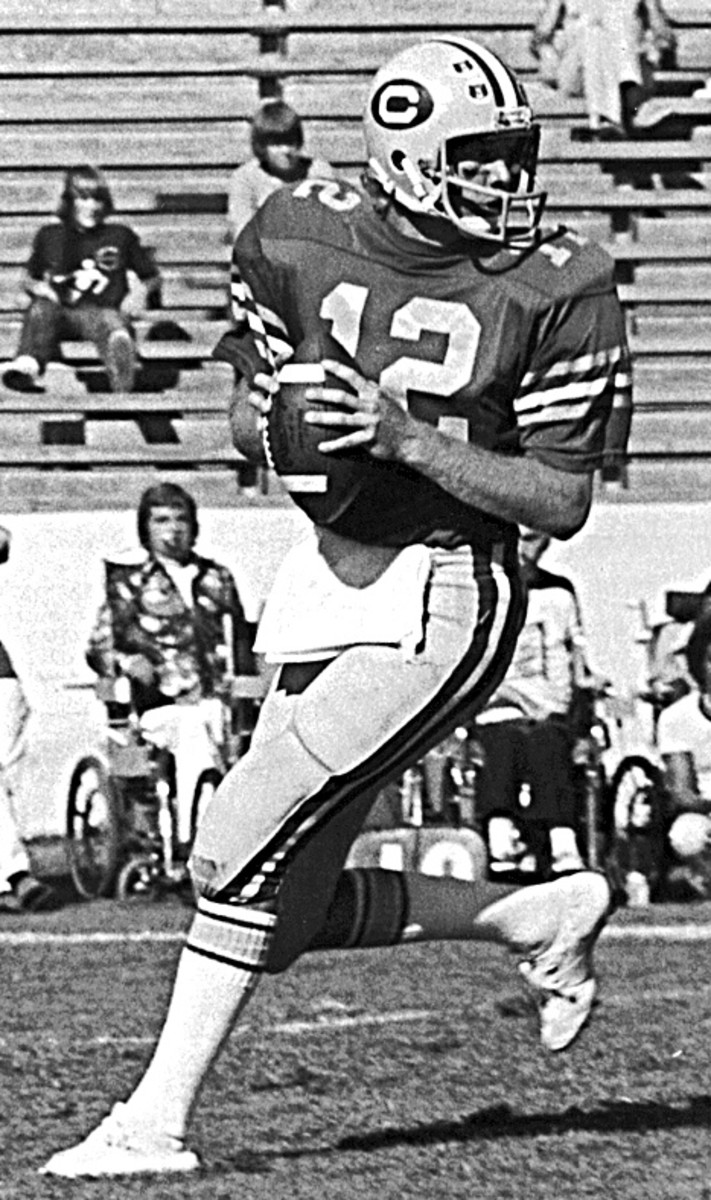

No. 20: Joe Roth

Cal Sports Connection: Roth led Cal to an 8-3 record and Pac-8 co-title in 1975 and finished ninth in the Heisman Trophy voting in '76 despite secretly battling melanoma.

Claim to Fame: After he died from the cancer in February 1977, Roth had his jersey No. 12 retired and Cal named the annual home game against either USC or UCLA in his honor.

.

More than 46 years after he died, Joe Roth lives on in the hearts and minds of so many Cal fans.

The former quarterback earned lasting respect not only for the way he lived his life, but the manner in which handled the final chapter.

“On and off the field, Joe was the finest individual I’ve been associated with in athletics,” said Mike White, Cal’s coach, after Roth died at the age of 21 on Feb. 19, 1977 following a battle against melanoma. “Joe had an impact on everyone he came into contact with.”

Thirty years later, in 2007, White was again asked about his former quarterback. And his passion for Roth hadn’t faded a bit.

"Words are hard to express what he did and what he meant to Cal football specifically,” he told the San Francisco Chronicle. “After all these years, it's very obvious just how important Joe was to a lot of people and the university. There aren't many people who fit in that category.”

Roth truly fits in a category all his own among former Golden Bears. His jersey number 12 is retired — the only Cal player who has received that honor. And every year, the team’s home game against either USC or UCLA is designated as the Joe Roth Memorial Game.

And now he resides at No. 20 in The Cal 100.

Roth came to Cal before the 1975 season from Grossmont Junior College in San Diego, where he showed great promise while overcoming his first bout with cancer.

He won the starting job by Week 4, leading the Bears to an 8-3 record and Pac-8 co-title. He passed for 1,880 yards with 14 touchdowns and just seven interceptions and inserted himself into the 1976 preseason Heisman Trophy conversation.

“The sky was the limit for him,” White told California Magazine in 2015. “He definitely would have been the first quarterback taken in the NFL draft. He had all the skills, plus a great work ethic. But most important, he had the temperament. The only other quarterbacks I’ve ever seen with a temperament like that were Joe Montana and Tom Brady.”

Unfortunately, the cancer returned. Roth was determined to play his senior season and do it on his own terms. So he kept the news a secret to everyone on the team except White.

Roth never complained, never missed practice, never changed the way he treated others. Matt Bouza, who went on to an eight-year NFL career as a wide receiver, was a freshman in '76.

“Most seniors wouldn’t even talk to freshmen,” Bouza said, “but on the first day of practice he came over to me, shook my hand, and said, ‘How are you doing, Matt? I’m Joe. Where are you from? What high school did you go to? Do you need anything?’ And it wasn’t just me; that’s the way he treated everybody.”

“He never thought of himself as The Great Joe Roth,” girlfriend Tracy Lagos McAllister said. “He was just Joe.”

Roth’s weight plunged from 205 pounds to 179 that fall and his performance dipped as well. He still passed for 1,789 yards, but his touchdowns fell to seven and his interceptions soared to 18. Even so, Roth finished ninth in the Heisman voting and was named first-team All-American by the Sporting News.

His terrible news finally became public, and Roth continued to try keeping it low-key.

“Really, just figure I’m a normal guy,” he told United Press International. “What if some guy sitting down there on the street corner got cancer? Would everybody make a big fuss?”

But Roth wasn’t just anybody. His final appearance was the Japan Bowl all-star game in January 1977, when he completed five of six passes he attempted.

Hospitalized for a week in early February, Roth was informed by his doctors they wanted to amputate both his legs to prolong his life. He said no and asked to go home.

His teammates carried him up two flights of stairs to his apartment, where he spent his final hours with family and friends. He died two days later.

Roth was posthumously awarded the Berkeley Citation later that year, an honor given to those "whose attainments significantly exceed the standards of excellence in their fields and whose contributions to UC Berkeley are manifestly above and beyond the call of duty.”

The Bears give out the Joe Roth Award after each season for courage, attitude and sportsmanship.

A few months after Roth's death, on a night when Roth might have graduated to professional football, commissioner Pete Rozelle opened the 1977 NFL draft with a moment of silence for the Cal star.

And in 2015, filmmakers Phil Schaaf and Bob Rider, who were school kids when Roth died but later attended Cal, released the acclaimed documentary, Don't Quit: The Joe Roth Story.

He lives on.

Cover photo of Joe Roth courtesy of the UC Regents

Follow Jeff Faraudo of Cal Sports Report on Twitter: @jefffaraudo