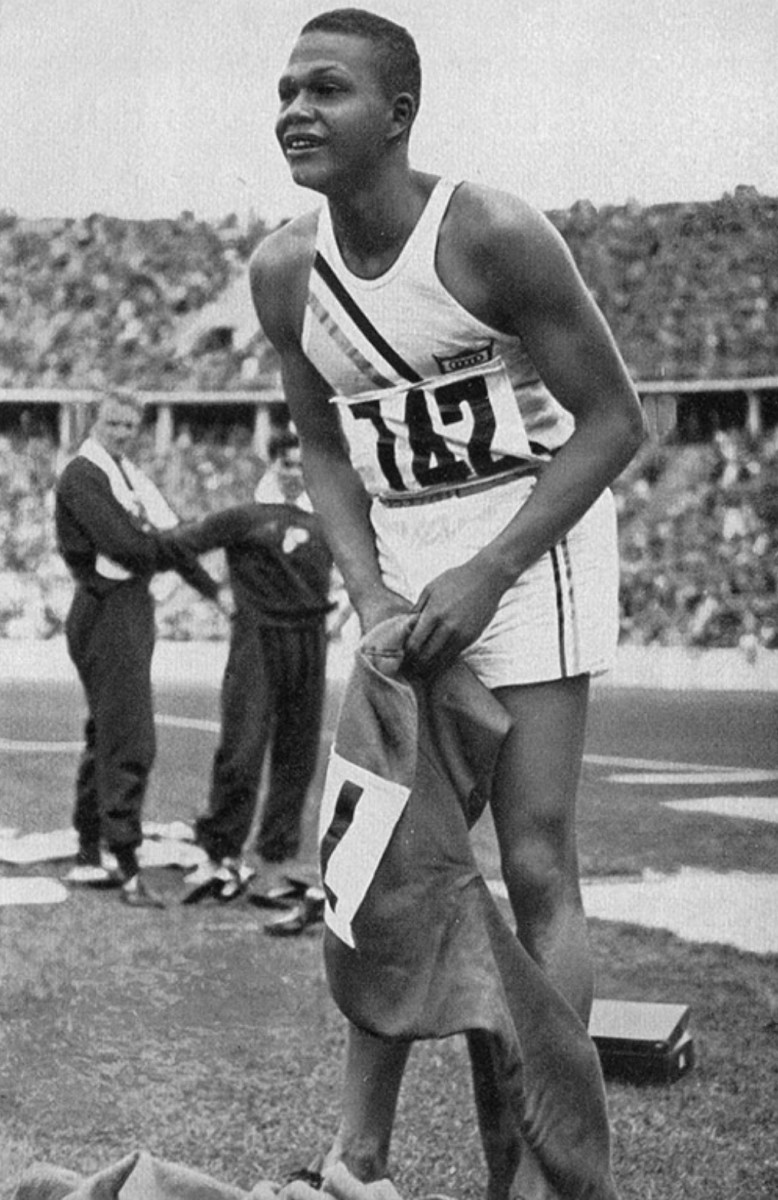

The Cal 100: No. 30 -- Archie Williams

We count down the top 100 individuals associated with Cal athletics, based on their impact in sports or in the world at large – a wide-open category. See if you agree.

No. 30: Archie Williams

Cal Sports Connection: Williams won the 440-yard dash at the 1936 NCAA championships, setting a world record in the process.

Claim to Fame: He ran for the U.S. at the '36 Berlin Olympics, capturing the 400 meters but not a handshake from enraged Adolf Hitler, then went on to an accomplished life as a flight instructor at the Tuskegee Army Flying School and, finally, a popular Bay Area high school teacher.

Archie Williams, who grew up in Oakland during the Depression, graduated from University High School then spent a year at College of San Mateo.

He ran track as a freshman at the junior college, but was more serious about his classroom aspirations.

After Williams won 19 of the 20 races he ran for San Mateo, coach Oliver “Tex” Byrd recommended him to Cal’s Brutus Hamilton, who made Williams one of the few Black athletes at Berkeley. Williams had never broken 49 seconds in his specialty, the 400 meters, and he wasn’t sure how good he could be.

“I was a nobody,” he was quoted saying many years later. "Nobody recruited me…and I didn’t care because I was going to play in the physics lab.”

He did not remain a nobody on the track for very long.

By the spring of 1936, at age 21, he set a world record of 46.1 seconds over 400 meters in a prelim heat of the (longer) 440-yard dash at the NCAA championships before winning the final. He then qualified for the Berlin Olympics, where Hitler expected his host German team to demonstrate the superiority of the Aryan race.

Jesse Owens famously won four gold medals, after which Hitler refused to shake his hand.

With less fanfare, Williams came from behind to win gold in the 400, his own contribution to undermining Hitler’s racist theology. “Hitler wouldn’t shake my hand, either,” Williams said.

The entire experience was overwhelming to Williams. “It was like a dream,” he said. “You were dreaming you were in something that you thought about before. ‘What am I doing here? Is this me?’ In fact, when it was over and I came back, did that really happen? Did I really do that?”

Williams’ out-of-nowhere performances in 1936 would be enough to land him in The Cal 100. But his No. 30 ranking is the result of a life so substantial that a Bay Area high school was renamed in his honor.

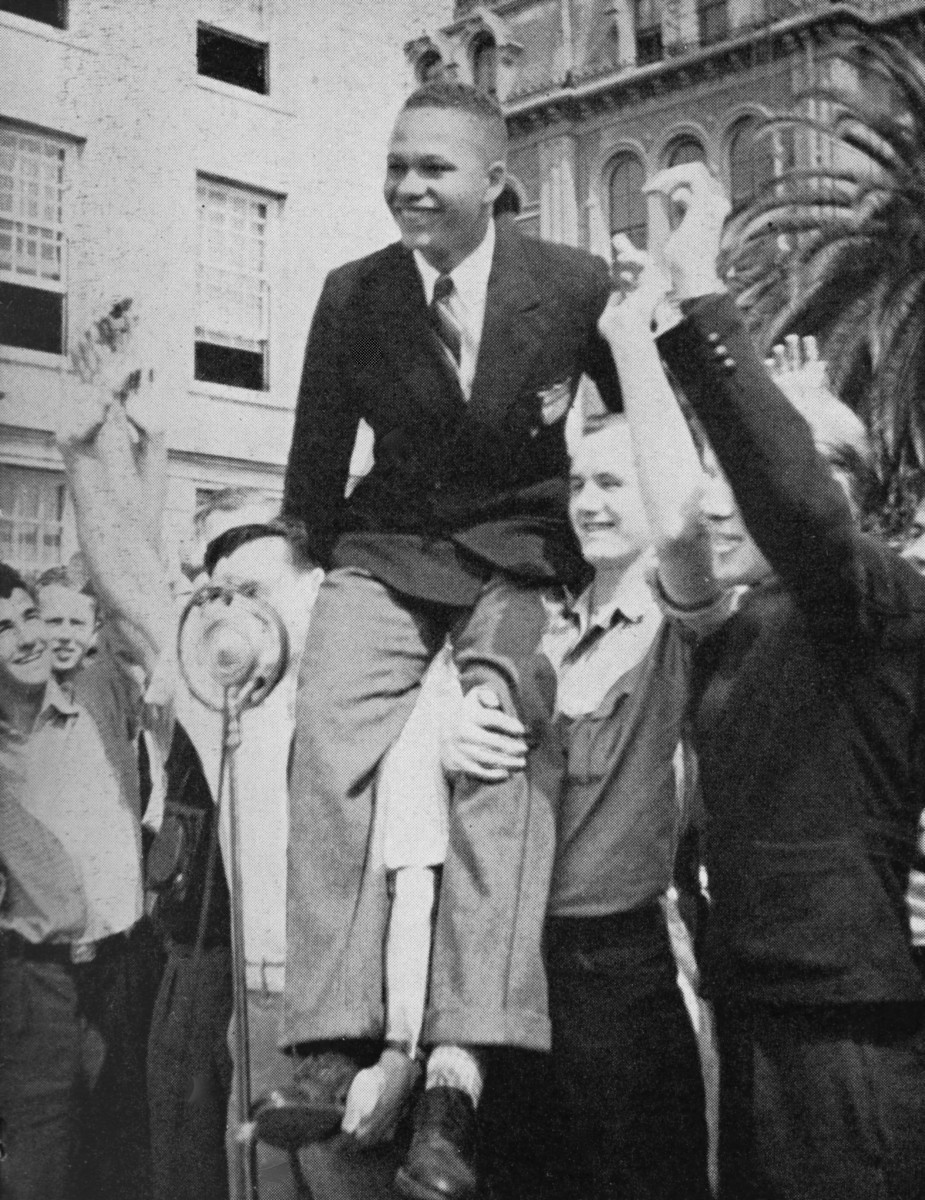

Upon his return from Berlin he was celebrated with a midday rally on the steps of Wheeler Hall on campus. But a gold medal didn’t change his life as a Black man in America in the 1930s.

"As I recall, when I came back home ... people asked me, `How did those dirty Nazis treat you?' To which I always replied, `Well, over there at least we didn't have to ride in the back of the bus,’ “ he said in a 1981 interview with the Oakland Tribune.

He suggested that Germans, unaccustomed to seeing Black people, were primarily curious.

"I think they wanted to see if the black would come off if they rubbed our skin. ... Jesse Owens might have been snubbed by Hitler, but he was a hero in the eyes of the Germans. They followed him around the streets like he was the Pied Piper.”

Williams continued to compete for Cal, although a hamstring injury prevented him from attaining the same success.

When he graduated in 1939 with a degree in mechanical engineering, his Cal diploma didn’t help him find a job, and he was briefly forced to dig ditches for the East Bay Municipal Utility District. "It was racism,” said Vesta Williams, his wife of 50 years. “They weren't hiring black engineers.”

Williams earned a commercial pilot license and in 1943 was hired as a civilian flying instructor at the Tuskegee Army Flying School, home of America’s first Black combat pilots. He eventually enlisted in the Air Force, for whom he worked as an instructor, weather officer and pilot while also studying meteorology at UCLA and aeronautical engineering at Wright Patterson Institute in Dayton, Ohio.

He flew missions during World War II and the Korean War and served as a military meteorologist before retiring from the military as a lieutenant colonel in 1964 after 21 years.

At 51 years old, Williams began a 21-year stint teaching math and computer science at Sir Francis Drake High School at San Anselmo, north of San Francisco. It was “beautiful,” Williams said of teaching. “I loved it.”

Williams died at age 78 in 1993, but he made a permanent connection to his old school in 2021 when it was renamed Archie Williams High School. In the wake of George Floyd’s killing, school officials decided it was no longer appropriate for the school to be named after a 16th-century explorer with a legacy as a slave trader.

Leslie Harlander, president of the Tamalpais Union High School District, said at the time, “Archie Williams is inarguably an individual who made tremendous contributions to our school, our community and to our nation.”

Cover photo of Archie Williams courtesy of Cal Athletics

Follow Jeff Faraudo of Cal Sports Report on Twitter: @jefffaraudo