EXCLUSIVE: John Wooten's legacy as a football trailblazer

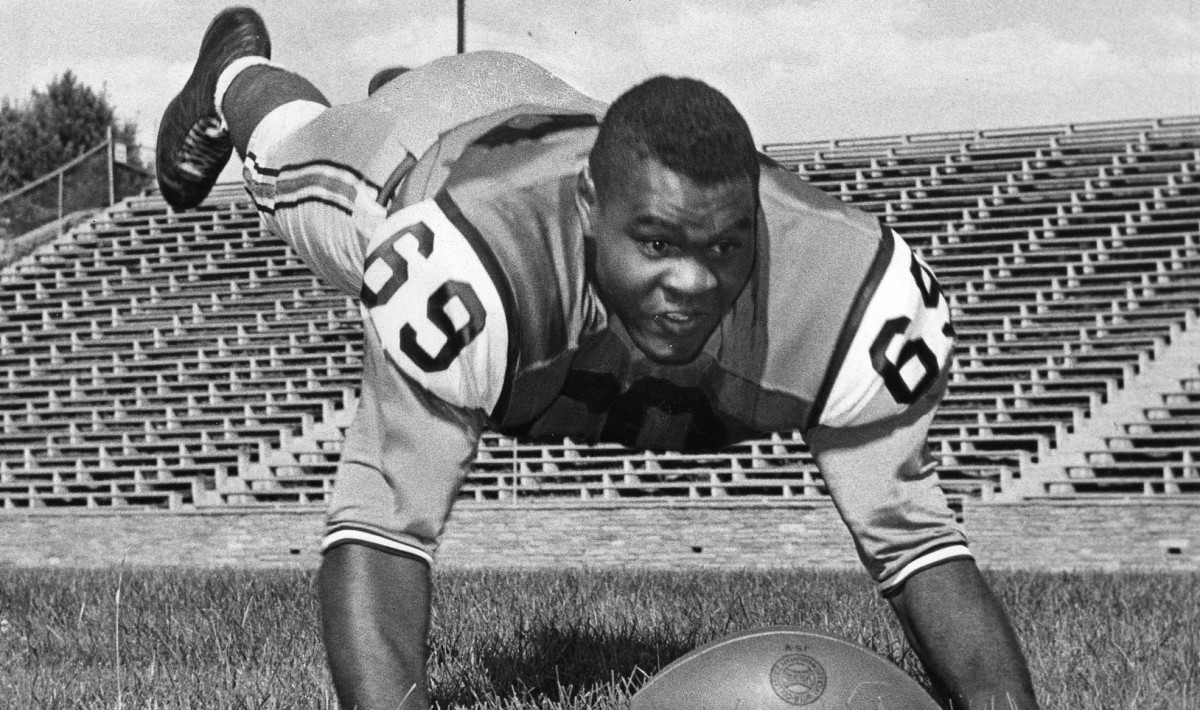

Colorado has nine former players and coach Bill McCartney enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame down in Atlanta. While all of them are deserving in their own right, none of them have a story quite like John Wooten.

The gentle giant took his career down a path of history. Whether he was the lead blocker for the great Jim Brown, a Civil Rights advocate who tried to help move the country in the right direction, or leader of the Fritz Pollard Alliance; Wooten's legacy will stand alone as legendary.

It all started in Riverview, Texas. The town between San Antonio and Waco as the crow flies is designated as Wooten's birthplace. John was the youngest of six children born to a single mother, who moved the family to Carlsbad, New Mexico, in a time of segregation. It was something he dealt with up until the tenth grade.

Wooten received offers far and wide for his play on the field. An Ivy league contender in Dartmouth to a California feeder school known as UCLA. But it was Colorado and Hugh Davidson which left a lasting impression on Wooten's mother. She ultimately made the decision for John to attend CU, which he has no regrets about six decades later.

"I can honestly say, (Colorado) was the greatest choice for me," Wooten said.

It was the lifelong relationships Wooten made in Boulder that was a difference maker. One of those was with Dal Ward. The multi-talented football coach for the Buffaloes thrived in Boulder going into the 1950s. He brought the program to national prominence shortly after settling into the Big Seven conference a few years prior. Ward also led CU to their second-ever bowl appearance-- a date in the 1957 Orange Bowl with Clemson.

Wooten was one of two African-Americans on the Buffs' team to play in Miami. A time in history seven years before the landmark Civil Rights Act. The American South was reluctantly conforming away from the ills of Jim Crow laws. Clemson rebuked the thought of playing Colorado and Tigers head coach Frank Howard loathed that his "white only" team was forced to share the field with two black CU players.

Clemson officials originally stated that they would give back an invitation, if they ended up against a team with black athletes. But they later changed their position. It was embarrassing to a degree with CU taking home a 27-21 win over Clemson. Frank Clarke was the unsung hero of the game with a pair of second-half touchdowns. CU's first black football player, who was two years ahead of Wooten, was known as a star wide receiver in an era when power backs dominated the game.

It marked the start of a path that led into the professional ranks for the duo of Wooten and Clarke. However, it was Ward's firm support of his players which kept them from being oppressed by others. The Buffaloes faced division in many of the places they traveled. Wooten noted it wasn't easy to stay in a hotel together across either Colorado state line into Utah or Kansas. He remembers the trip to Miami vividly and the attitudes of the Bal Harbor hotel owners had towards them.

"This was New Year's Day in 1957. Coach Ward made his presentation to the hotel that if Frank or I couldn't stay together with the rest of the team, we were all leaving," Wooten recalled. "They could tell the Orange Bowl committee we were headed back to Boulder. Our team captains took the lead in saying, "Hey, we all travel together," and everyone stays in one place."

In the late 50s, bowl games were a big event with activities surrounding the two teams being featured. Except the natives of South Florida didn't take kindly to allowing Wooten and Clarke to be a part of any of the festivities. And Ward wasn't having that whatsoever. He promised his team would be showing up to events in complete unity, but it still wasn't enough.

"We understood the segregation that was going on in the country, and we weren't going to create any problems," Wooten said. "All the team activities went on, and we went over the black area of Miami. Everything worked out fine."

The Orange Bowl committee was at the point of trying to bring in different teams from out west. Colorado finished the 1956 regular season with a 7-2-1 record in the Big Seven with No. 1 Oklahoma going undefeated at 10-0, but they did not play in a bowl game due to the conference's "no-repeat" rule. Thus, runner-up Colorado received the invite.

"Remember now, this was an era when you had four major bowl games," Wooten said. "It wasn't like how it is today with 60-some bowl games. This was a major game. All those games were played on the same day."

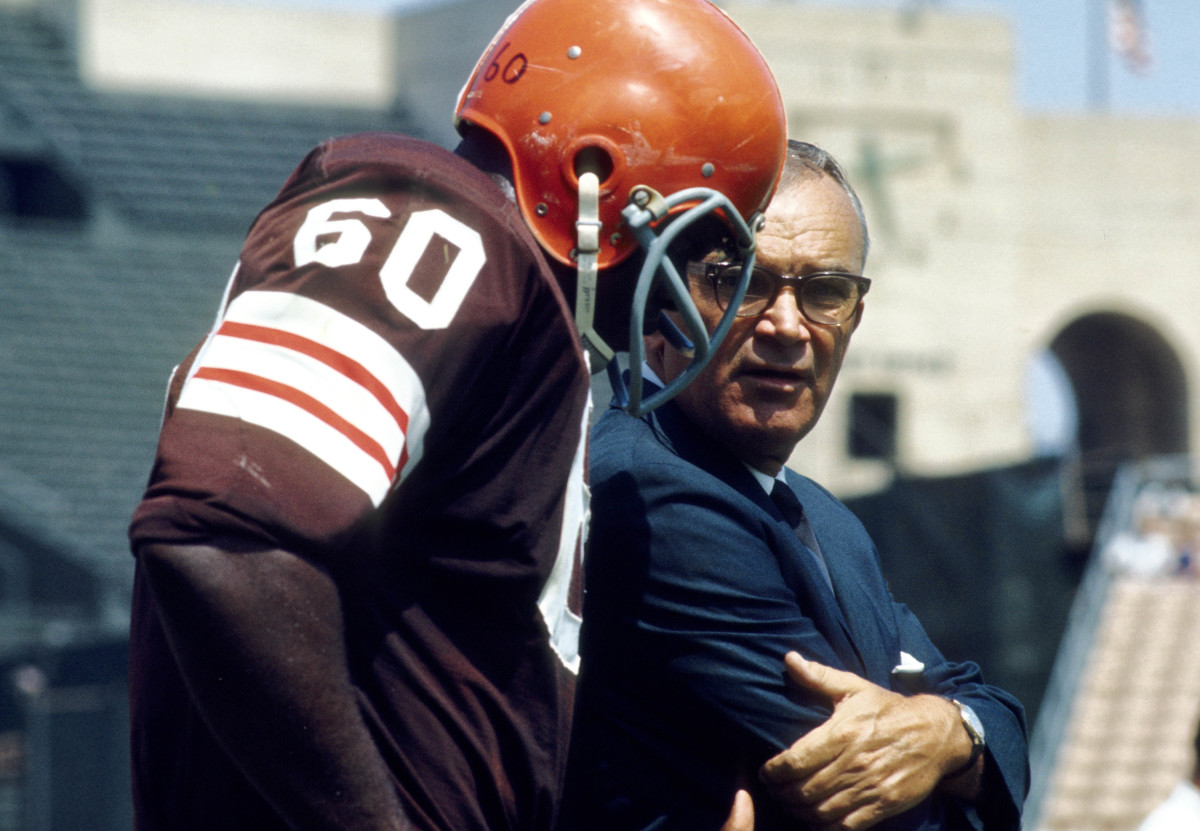

The 1957 Orange Bowl was the defining moment of Wooten's college career at Colorado. Two years later, he went on to be a fifth-round draft pick of the Cleveland Browns and was reunited with Clarke, who was taken by the storied NFL franchise following CU's win down in Miami. They were teammates for a year before Clarke was part of the Dallas Cowboys' Expansion Draft in 1960.

Wooten didn't expect his role in the NFL to be looked upon by the eyes of the world. The man, best known as Jim Brown's favorite blocker, used his leverage outside the field.

Move ahead to June 4, 1967 in Cleveland. A group of well-known athletes demanded change for a better tomorrow. A Sunday meeting with twelve men. Muhammad Ali, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Bill Russell, Bobby Mitchell, Willie Davis, Walter Beach, Curtis McClinton, Jim Shorter, Carl Stokes, and Sidney Williams stood with Brown and Wooten. They organized a response to Ali's refusal to enter the draft for the Vietnam War. It was Brown's idea to call the press conference, giving the eleven athletes and one politician a show of solidarity.

"Jim Brown and I had a great relationship with Ali," Wooten said. "He was part of our group. A very strong part of the group called the Black Economic Unit. But our concept was to advocate for change. Ali didn't step forward. You see that in the picture of all of us. We needed to be heard."

In July 1968, Wooten demanded a trade from the Browns after a reported dispute with the organization spurred by an "all white" Browns' company outing. Browns owner Art Modell denied and eventually released him days later. He played his final season in Washington but has dedicated his time to making the NFL better.

After retiring as a player, Wooten went from being an agent to a executive with the Cowboys, Eagles, and Ravens. A full-circle moment due to the original Browns franchise moving to Baltimore in 1995. He stayed with the Ravens until 2003 and moved over to become the Chairman of the Fritz Pollard Alliance, an advocacy group who works in conjunction with the league for equality.

Wooten is credited with an NFL Championship with the Browns in 1964. He also won two Super Bowls as an executive (XII- Cowboys, XXXV- Ravens).