Remembering Iowa's 1st Conference Title Team

IOWA CITY, Iowa - The University of Iowa started playing football in 1889. For the first seven seasons, the coaching was done by members of the athletic board, “members of the faculty or other interested persons,’' according to a retrospective story that appeared in the Des Moines Register in 1932.

That changed in 1896, when A.E. Bull was hired as the Hawkeyes’ first official head football coach. The Cedar Rapids Gazette reported in October of 1986 that Bull’s salary would be “$500 for three weeks service.”

Bull, who played at the University of Pennsylvania and was an all-America center in 1895, brought a winning touch to the program even though his loyalty was unwavered.

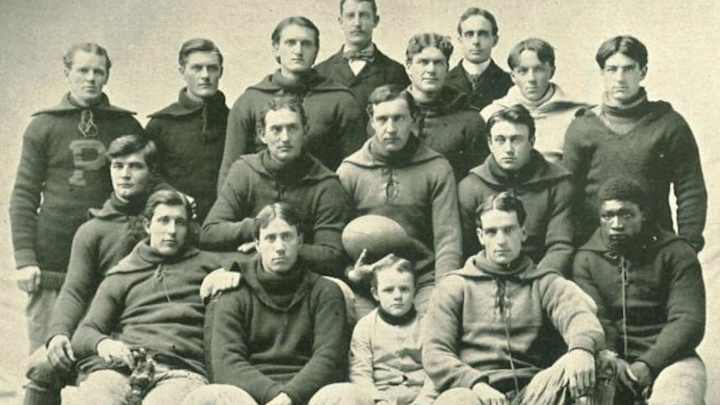

In an 1896 team picture that appeared in the University of Iowa “Hawkeye” yearbook, Bull stands in the top row, first on the left, dressed in a University of Pennsylvania football sweater.

He inherited an Iowa program that had finished last or tied for last in the Western Interstate University Football Association standings for four straight seasons. The Hawkeyes were 2-11-2 in conference play over those four seasons. Also in the four-team league were Kansas, Nebraska and Missouri.

But Bull’s 1896 team earned the school’s first conference football title ever, finishing 2-0-1. Kansas was second at 2-1. That loss was a 6-0 decision in Iowa City in the third game of the season. The Hawkeyes finished 7-1-1 overall after being 2-5 the year before.

It was the kind of turnaround that brings to mind Iowa’s famed Ironmen of 1939 and Hayden Fry’s 1982 team that snapped a streak of 19 consecutive non-winning seasons with a trip to the Rose Bowl. The 1939 Ironmen had 1939 Heisman Trophy winner Nile Kinnick and finished 6-1-1. Iowa had been 1-7 and 1-6-1 the previous two seasons.

Bull’s reputation as a great player was matched by his coaching ability.

“Bull was respected not only as a player but also as a likable, conscientious football coach, well grounded in the fundamentals of the game,” wrote Dick Lamb and Bert McGrane in their book, “75 Years With the Fighting Hawkeyes.” “The Hawkeyes responded to his teaching with seven victories, one loss and a tie, the finest season-long performance made up to that time by a team from the state of Iowa.”

In its writeup on the 1896 season - “Foot Ball Team” - The “Hawkeye” yearbook listed officers of the squad. It included this description: “Bull, of Pennsylvania, Coach.”

The 13-member team included a man named F.K. Holbrook. Frank “Kinney” Holbrook was the first African-American to play football at Iowa, the first in the state of Iowa and one of the first in the nation.

The son of runaway slaves, Holbrook was from Tipton. He was the community’s first African-American high school graduate in the spring of 1895. That fall, he started his Iowa career as a left end.

With the coaching change came a new position in 1896. Bull watched Holbrook and decided he was better suited as a running back. It was a decision that had championship implications.

“Kinney Holbrook, perhaps the state’s first Negro gridder, must go down as one of the all-time greats at Iowa,” Lamb and McGrane wrote in “75 Years With the Fighting Hawkeyes.’ He was a champion sprinter, the most dependable Hawk defensive man, as well as the team’s leading scorer.”

Holbrook, the left halfback, scored 12 touchdowns in 1896. The “Hawkeye” yearbook called the 185-pounder “one of the best half-backs in the west. He was generally given the ball when a good gain was needed on the last down. His line bucking was excellent. In falling on the ball after a fumble, he has his superior yet to meet. His ability lay in great part to his strength and sprinting qualities.”

Iowa’s 1896 season started with a 32-0 victory over Drake, and was highlighted by Holbrook’s four touchdowns.

The only loss of the season came the following week, a 6-0 defeat to Amos Alonzo Stagg’s powerhouse Chicago team. Wrote Lamb and McGrane, the Chicago Times-Herald reported that “Iowa’s star work was done by Holbrook. It was brilliant. He made one run of 40 yards through a forest of Chicago tacklers and a couple of sprints of 30 yards. Iowa always worked him when it was necessary to make a gain to keep the ball.”

A week later, Iowa’s 6-0 victory over Kansas came on Holbrook’s 45-yard touchdown run. That was the first of three consecutive shutout victories for the Hawkeyes. A 27-0 victory over Wilton followed, then came a racially-fueled 12-0 victory at Missouri.

Alumni and citizens in Columbia, Mo., demanded that Holbrook not be allowed to play because he was black. University of Iowa officials said there would be no game if Holbrook was not allowed to play. Holbrook scored a touchdown in the victory.

Iowa had clinched a share of its first conference victory when it met Nebraska in the season finale on Nov. 26 at University Park in Omaha, Neb. The Cornhuskers could earn a share of the title with a victory.

The Thanksgiving weather was horrible, turning the field into a sheet of ice. The game finished in a 0-0 deadlock. That tie guaranteed Iowa the conference title outright. But the Hawkeyes agreed to play Nebraska again two days later.

Iowa won the rematch, 6-0, and Holbrook provided the points with a 30-yard touchdown run.

“That man, Holbrook, colored, is a crackajack on the run,” the Omaha World-Herald reported.

The game was again played in terrible weather.

“Foot ball players are oblivious to all kinds of weather as was demonstrated by the meeting of Iowa and Nebraska universities at Omaha on Thanksgiving day and Saturday,” the World-Herald reported. “Possibly no two teams in the west ever entered the field in such disagreeable weather. The supporters of the teams and followers of the game were imbued with hardihood almost to the same extent as the players, in spite of heavy rain, sleet, snow and a biting wind Thursday they turned out in strong numbers and remained while the ground changed from slippery mud until it became so hard that it resembled a first-class hockey ground.”

Iowa’s 7-1-1 record in 1896 included seven shutouts. The Hawkeyes outscored their opponents 126-12. Iowa had failed to score a point in the five of the seven games it played in 1895.

Bull left Iowa after one season to become the coach at Franklin & Marshall. He later coached at Georgetown, Lafayette and Muhlenberg, compiling a 62-34-15 record before leaving the profession. He practiced dentistry the next 30 years in Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

Holbrook, who also lettered twice in track at Iowa, left school and returned to Tipton to work as a blacksmith. He died of a heart attack in 1916 at 39 years of age.

Holbrook’s status as the first African-American to compete athletically and in the state of Iowa was forgotten until many years later.

Former Iowa wide receiver Quinn Early helped bring Holbrook’s career to life by producing a 35-minute documentary about him called “The Shoulders of Giants.” And when Frank Kinney Holbrook was enshrined in the University of Iowa Athletics Hall of Fame in September of 2021, Early was there to accept the award for one of the giants of Iowa football history. Quinn was a four-year letterman at wide receiver for the Hawkeyes (1984-1987).

“And because he truly was a giant I got to follow in his footsteps, along with all the other black athletes who followed, because of Frank Kinney Holbrook,” Early said in the documentary.