MICHIGAN STATE ATHLETICS ANNOUNCES 2018 HALL OF FAME CLASS

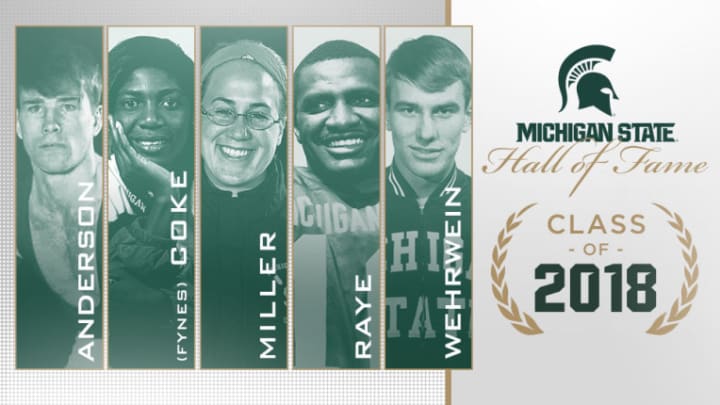

EAST LANSING - Michigan State will induct five Spartans into its Athletics Hall of Fame on Thursday, Sept. 27 as part of its annual "Celebrate" weekend. The 2018 Hall of Fame Class includes: Dale Anderson (wrestling), Savatheda (Fynes) Coke (track & field), Rachel Miller (rowing), Jimmy Raye (football), Bill Wehrwein (track & field).

The Celebrate 2018 weekend includes the ninth-annual Varsity Letter Jacket Presentation and Hall of Fame induction ceremony on Thursday, Sept. 27 and then a special recognition of the Hall of Famers during the Michigan State -- Central Michigan football game at Spartan Stadium on Saturday, Sept. 29.

The MSU Athletics Hall of Fame, located in the Clara Bell Smith Student-Athlete Academic Center, opened on Oct. 1, 1999, and displays key moments in Spartan Athletics history as well as plaques of the 144 previous inductees. The charter class of 30 former Spartan student-athletes, coaches and administrators was inducted in 1992.

"I'm in awe at the list of credentials for this year's Hall of Fame class," Michigan State Athletics Director Bill Beekman said. "This group has combined for 14 All-American honors, 12 individual Big Ten Championships, six individual NCAA Championships and three team NCAA Championships. In addition they have captured Olympic gold, been recognized for academic excellence, helped launch a new sport at MSU, and perhaps most importantly, been a key figure in the integration of college football across the nation.

"Dale Anderson is one of the most decorated Michigan State wrestlers of all time. He excelled on the mat, as one of just five two-time NCAA Champion wrestlers in school history. His individual success included three Big Ten titles and three All-American honors. But he's just as proud of the team's success of three conference championships and one national title during his wrestling career. For all his athletic success, his academic performance was just as strong, posting a perfect 4.0 GPA during his NCAA Championship season in 1967, and being selected as MSU's 1968 Big Ten Medal of Honor recipient.

"Savatheda (Fynes) Coke absolutely made the most of her one year of competition as a Spartan. You could make the argument that her 1997 season was the best ever for a female sprinter in Big Ten history. She won more NCAA titles that year (three) than any Spartan has ever won in their entire career. While track and field is often thought of as an individual sport, she also understood she always represented something bigger than herself, whether it was Michigan State or the Bahamas, for whom she competed in both the 1996 and 2000 Olympics, capturing Olympic Gold in Sydney in 2000.

"Rachel Miller was the first First-Team All-American in MSU rowing history, and remains the only three-time honoree, while also earning recognition as a scholar-athlete. She helped the Spartans reach the NCAA Championships in each of her four seasons, the final three in the varsity eight. It's fitting that Rachel is a part of the Hall of Fame Class of 2018, being the first rowing inductee 20 years after the program's inaugural 1997-98 season.

"There's no doubt that Jimmy Raye was an outstanding football player, leading the Spartans to the 1966 National Championship as the starting quarterback, and being a key member of the 1965 national championship team. But Raye's impact goes far beyond his stats. As the first African-American starting quarterback from the South to win a National Championship, Raye was part of a groundbreaking football integration movement that changed college football forever. His teammates talk about the way his leadership embodied the togetherness that existed on those championship teams. Raye's induction shows that the power student-athletes have extends far beyond the field of play.

"Bill Wehrwein competed during one of the greatest periods of MSU track and field, excelling both as an athlete and as a team leader. His NCAA Championship, five Big Ten Championships and four All-America honors speak for themselves, but his value as a leader ensured that MSU track and field would continue to excel. His competitive spirit, leadership and loyalty were an example for Hall of Famers who followed him."

Dale Anderson

Wrestling (1965-68)

Waterloo, Iowa

The unmatched overall success of Michigan State athletics in the mid to late 1960s produced some of the most accomplished student-athletes in the history of the university. A total of seven national championships across four sports in a three-year span formed legacies that are still revered today.

The Spartans' success came from student-athletes of diverse backgrounds from all parts of the country, including one from a small Iowa farm with no running water and no electricity. Dale Anderson was born on that small farm near Fort Dodge, Iowa, and from those modest beginnings he went on to be one of the top wrestlers in the country and a two-time national champion.

It was after moving to Waterloo, Iowa, that Anderson became more immersed in the sport of wrestling. By his junior year he had done enough to earn a visit from Michigan State wrestling head coach Grady Peninger, who came bearing a scholarship offer.

"To receive a full-ride scholarship was very rare in 1960s,"Anderson said.

His success on the mat -- and in the classroom -- continuing to trend upward as a senior, Anderson garnered interest from just about every wrestling program in the country.

"My old high school coach seemed to be my PR guy and knew all the college coaches," Anderson said. "He said to me my senior year, `you'll be a national champion.'"

With Ivy League and Big Ten schools all competing to land the athletically and academically accomplished Anderson, the Iowa native decided to stay home, enrolling at Iowa State. But, his decision soon changed again.

"I transferred after the first term," Anderson said. "I felt bad that I didn't go to Michigan State and that was mainly because of the coaches in Grady and Doug (Blubaugh) -- they were great coaches I wanted to wrestle for them."

Anderson's decision to transfer to Michigan State provided a huge boost to a program on the rise. Under head coach Grady Peninger, the Spartans won their first of seven consecutive Big Ten titles in 1965. The following year in 1966, Anderson won his first Big Ten title at 130 pounds, as MSU claimed another team championship.

While the Spartans were kings of the Big Ten, they were looking to further establish themselves on the national stage. The Spartans' confidence increased as the season progressed, buoyed by a regular-season win over perennial national power Oklahoma.

"The song `Respect' by Aretha Franklin was new then and it was kind of our theme song," Anderson said. "We took on that song as our own. The only way you get respect is to go out there and earn it. We went from not being able to get our girlfriends to come watch us wrestle to having thousands people at a meet.

"Things fell into place that season. We certainly didn't go into year thinking that we were going to win the national championship; we were nobodies in the wrestling world. We just wanted respect."

Respect came the Spartans' way as they won the 1967 national championship. Anderson also claimed his first of two individual national crowns at 137 pounds, capping an undefeated season (25-0) by beating Masaru Yatabe of Portland State.

Known for his intensity and aggressiveness, Anderson harnessed those qualities to outlast Yatabe, 3-2 in overtime after ending regulation tied, 6-6.

"Going into the 1967 championship match, I so anxious and that totally wore me out," Anderson said. "I wanted to win so badly and when you want to win too much, you wear yourself out. I was so exhausted in that title match my junior year, yet was able to get it to OT and won."

Anderson's year didn't just end with a team and individual national title and unblemished record, he also went "undefeated" in the classroom.

"I got a perfect 4.0 that year," Anderson said. "Coincidentally when grades came out after the national championship, I found out I got a 4.0. President John Hannah was proud of me; I liked him, he was a great guy."

As a senior the following season, Anderson and the Spartans won another Big Ten crown as he captured his second straight individual conference title. MSU took fourth as a team at the 1968 NCAA Championships and Anderson again found himself in the national title match against a familiar foe, Yatabe. But another year of experience had Anderson entering the championship bout better prepared.

"The 1968 match was a million times easier than the prior year," Anderson said. "Even though I was five points down at one point, I knew I could come back and beat him.

"I was so relaxed, I had already won a title the previous year and I felt really good and confident. I knew he was a better wrestler and knew I was more intense than him; I would wear him out and that's what I did. I wore him out both years."

Anderson did exactly that, topping Yatabe, 9-5, to win the national championship. He is one of five two-time NCAA Champions in Michigan State history.

Anderson's dedication in the classroom was again recognized as he was named MSU's recipient of the Big Ten Conference Medal of Honor, which is awarded annually to a male and female athlete at each of the Big Ten institutions to the students demonstrating the greatest proficiency in scholarship and athletics.

He ended his Spartan career with a record of 61-4-1 and his .932 winning percentage ranks fourth in program history.

The Spartans' success and national championship spurred Anderson to author a book about the team's dream season. In 2016 Anderson published A Spartan Journey: Michigan State's 1967 Miracle on the Mat. The book chronicles the Spartans' run to the title, but also notes the great success of all MSU programs at the time.

"When you're in the middle of something like that, you really don't think about it," Anderson said. "I enjoyed going to see some of the other teams compete, like gymnastics, swimming and track. We had a lot of great sports outside of football and you just expected success from other teams. We had zillions of big men on campus -- just so many great athletes. Like I said, you were just expected to win and that came from President Hannah and Biggie Munn -- they were the catalysts that made this happen."

In fact, it was a Spartan legend from another sport that had a great impact on Anderson writing the book.

"One of the things that really inspired me was what Magic Johnson said to the 2000 National Championship team - that they would not fully appreciate what they had done for a long time. That's what happened to me -- I didn't fully appreciate what we did in 1967 until later. After 50 years, I said that was a really neat thing we did. It really hit me that we did something special."

Anderson, who earned his law degree from the University of Virginia, went on to a notable career as an attorney and still practices Constitutional law.

Savatheda (Fynes) Coke

Track & Field (1996-97)

Coopers Town, Bahamas

Her success has been global from a humble beginning in the Bahamas to collegiate success at Michigan State and international accomplishments in the Olympics. Savatheda (Fynes) Coke has been a winner at every level. Intertwining dominating at both the collegiate level and the international scene, Coke made the most of her time at Michigan State.

While entering the Michigan State Athletics Hall of Fame was not an accolade that she was expecting, Coke is honored to be joining some of the all-time greats in Spartan history.

"I am really excited to be entering into the Michigan State Hall of Fame. I think that it is a great honor that they have chosen me to be a part of this. I always have to thank MSU for supporting me," Coke said.

Coke transferred to Michigan State in 1996 after one season at Eastern Michigan. During her one season at EMU, she won an amazing five MAC titles. She also captured her first NCAA Outdoor title in the 200m in 1995 with a time of 23.63 seconds.

Despite the fact that her time at Michigan State was brief, she made a lasting impact on the Spartan track and field program. Her 1997 season ranks among the most accomplished in Michigan State track and field history.

In the Big Ten Championships, she won four titles during the stellar 1997 campaign. She won both the 55 and 200m titles at the Indoor Championships, and the 100 and 200m titles at the Outdoor Championships.

Coke is the only Spartan track and field athlete to win three national championships, including two during the 1997 outdoor season. She captured the NCAA indoor title in the 55m, with a time of 6.65. Coke was also the NCAA Division I Women's Outdoor Champion for the 100m and 200m, clocking 11.04 and 22.61 seconds, respectively. She is one of only two Big Ten athletes along with Nebraska's Merlene Ottey to capture the NCAA title in the 100m and the 200m in the same season. Her two outdoor titles allowed her to score 20 of Michigan State's 24 total points, leading the Spartans to a ninth-place finish, the highest NCAA finish in program history.

"I was excited about the meet in 1997, especially to be in the NCAA Championships. It was such an honor to compete for Michigan State. It was really a thrill to be a part of the MSU program. To be able to be the champion in both the 100m and the 200m was amazing. I was happy for Michigan State and us as a team," Coke explained.

In total, Coke earned four All-America honors in 1997, being recognized in the indoor 200m in addition to her three national titles.

The Coopers Town, Bahamas, native still holds the Michigan State indoor record in the 55-meter dash (6.65) and the 200-meter run (23.24), which were both set in 1997. While Coke knows that several of her records still stand, she is sure that a Spartan around the corner is waiting to see these records fall.

At the conclusion of the 1997 outdoor season, the All-American earned Michigan State's highest honor: the George Alderton Female Athlete of the Year award. She is one of just 11 MSU track and field athletes to earn the accolade along with Leah O'Connor (2015), Beth Rohl (2013), Emily McLeod (2011), Nicole Bush (2009), Jamie Krzyminski (2003), Susan Francis (1994), Misty Allison (1992), Odessa Smalls (1987), Judi Brown (1983) and Molly Brennan (1982).

During her well-decorated tenure as a Spartan, Coke spent much of her time doing a balancing act between her time with her MSU squad and her Bahamian teammates. She seamlessly went from the Atlanta Olympics to East Lansing to the Sydney Olympics. She never once lost sight of one of her goals: a degree from MSU.

"It was really easy to go back and forth from competing for the Bahamas and for Michigan State. Once you set goals for yourself, for me everything kind of fell into place. Education always comes first and athletics was second. So I had to try balancing both of them. So it was a matter of me focusing and dedicating myself to both track and academics," Coke said.

She went on to win silver in the 4x100m relay at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, and the following year won bronze in the 100m at the 1997 World Championships. She is the first Bahamian to win a medal in that event.

Following the completion of her Michigan State career, she continued to see her star rise. Despite a string of injuries, she was determined to return to the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, Australia.

"It was because of Michigan State that I was able to have these opportunities. It is because of MSU that I was able to compete at the Olympics for the second time. I am definitely grateful to Michigan State for even giving me that chance," she said.

The 2000 season was the pinnacle of her professional career. She placed seventh in the 100m at the Olympics in Sydney. Coke and her 4x100m relay team of Chandra Sturrup, Pauline Davis-Thompson and Debbie Ferguson were affectionately known as the "Golden Girls" en route to winning the Gold medal for the Bahamas in the relay with a time of 41.95.

Coke was fast out of the blocks and gave her team a commanding lead that no one caught. She, as well as her teammates, returned home to the Bahamas with much fanfare.

"It is always an honor to represent either your school or your country. We were just happy to be able to represent the Bahamas. The warm welcome that we got when we returned I did not expect. It made us feel like all of the hard work that we put into training and the disappointments of injuries or whatever else were worth it. The team supported us and the country supports us the same way that Michigan State was supporting me," Coke said.

The injury bug continued to plague Coke after the Olympics and she was eventually forced to hang up her spikes in 2008.

Despite her retirement, she did not say good bye to her beloved sport of track and field. She continues to stay involved in the sport through coaching at both the high school and college levels.

"I really have to acknowledge the coach at the time, Coach Darroll Gatson. He definitely helped us a great deal. I think he worked really hard when it came to helping us to get to where we were. I think that he made a lot of sacrifices for us to get there," Coke said. "And then of course there were my teammates. Shermaine McKenzie was always there to encourage me when I was down about something or riddled with injuries. She was there any time something wasn't going well. She was always there to keep my spirits uplifted."

Her hard work and sacrifices are rewarded as she join an illustrious group of Spartans in the 2018 Michigan State Athletics Hall of Fame.

Rachel Miller

Rowing (1999-2003)

Meeteetse, Wyoming

On Rachel Miller's undergraduate bio page on the Michigan State Athletics website, she offered the following quote.

"Rowing sneaks its way into your soul to surprise you. One day you finally realize that it is a dynamic part of what makes you....you."

It's a quote that still resonates with her to this day. She's more aware of it when she comes back to campus, attends MSU rowing alumni events, or attends regattas. And as someone who was introduced to rowing only when she got to campus in the fall of 1999, it's something that helped make her the most decorated athlete in the early days of the Michigan State rowing program. Joining the team as a freshman -- when it was in just its third season as a varsity sport at Michigan State - rowing was almost as new to East Lansing as it was to the freshman who came to campus and subsequently earned All-America honors three times.

A sport long dominated by teams on both coasts, the new Spartan varsity rowing program made a sizeable statement right away. During the crew's inaugural 1997-98 season, MSU became the first school ever to qualify a varsity eight for the NCAA Championships in its first year of collegiate competition. In 1998-99, MSU became just the second school to earn a team bid to the Championships during its second year of competition. The head coach was Bebe Bryans (now the head coach at Wisconsin), and her assistant was now-MSU head coach Matt Weise, who has been on staff for the entirety of its varsity existence after serving as the head coach of the club team before its elevation as a varsity sport.

Under the direction of Bryans and Weise, the program was already off to a hot start when Miller found her way to East Lansing from rural Meeteetse, Wyoming, in the fall of 1999. She was her class valedictorian and a member of the National Honor Society member who earned All-State honors in basketball and was an all-conference volleyball player, and also ran track. She was a member of the school's student council who participated in both drama and choir -- so a variety of interests and trying different things wasn't exactly straying off the beaten path for Miller.

"From the time I was small, I was involved in sports. I love being on a team and the purity of athletic competition along with sportsmanship," admits Miller. "I come from a family of teachers and so there was also a strong focus on academics. As I started to look beyond high school, I knew that I needed academic scholarships to be able to afford to go to University."

A unique opportunity for Miller came in the way of Michigan State's STARR Charitable Foundation Scholarship. Arranged by an anonymous private donor, the STARR scholarship is for high school seniors who reside in the State of Wyoming and in the Upper Peninsula of the State of Michigan. In addition to a strong academic background, candidates must be ambitious, talented, and enthusiastic in their academic and extracurricular activities, as well as exhibit leadership traits and demonstrate extraordinary skills, talents, curiosity to learn and grow, good moral character and unique characteristics that distinguish them from their peers.

"During the interview, I mentioned that my mother had been diagnosed with breast cancer my senior year of high school," remembers Miller. "Jack Shingleton [a longtime MSU administrator who by then had retired and was serving on the MSU Board of Trustees}, understood as he too had been touched by breast cancer. I'm still incredibly grateful to Jack Shingleton. The selection board took a chance on me and I will forever be thankful."

As it does every year, the rowing program was actively recruiting at freshman AOP activities when Miller arrived on campus in the fall of 1999. The coaches seek athletes who aren't playing their sports at the collegiate level -- some of the biggest rowing success stories on campuses nationwide are former high school standouts who weren't playing their sport at a Division I institution, but could learn the techniques and technical aspects of rowing. If they poured commitment and effort into their new sport, it could allow them to be a part of a successful, championship-level program on the water. Miller remembers being handed a postcard during her first days on campus that advertised the opportunity to try out for this new sport. She quickly learned that it was going to be just what she wanted and needed as a former three-sport scholastic standout back in Wyoming.

"I love being a part of a team and the family feel of the rowing team was a perfect fit for a small town girl far from home. At novice rowing tryouts, I developed friendships that I still have today. As for the sport, I wouldn't say I enjoyed getting up at the crack of dawn but once we were in the boats and on the water there was not a better way to start the day. The calm water of the river, the sun rising, and the feeling of the boat moving as we raced across the water... I loved it!"

As a true freshman in the spring of 2000, Miller quickly earned a spot in MSU's second varsity eight. The first-ever Big Ten Championship was held in Madison, Wisconsin, and MSU finished second to Michigan. This helped propel the Spartans into the NCAA Championship regatta. The Spartans led wire-to-wire in the petite final to claim a seventh-place finish in the 2V race, which helped MSU to an eighth-place team finish.

Weise was Miller's coach her freshman year. "Rachel was a powerful rower right from the start. She was pulled up from the novice eight to the second varsity eight during the spring of her freshmen year. Rachel was able to handle a great deal. She seemed to be unfazed by the workload that rowing required and she helped raise the standard of performance for our team both on and off the water.

"Once we had decided to move her up into the second varsity eight, we did a race piece in one of those first practices," he recalled. "I asked the boat how it went. The vets in the boat said, `It was bit rocky and a little wild.' I then asked, `Was it faster?' They responded, `Yes, by a lot.' That was Rachel in a nutshell in those early days. I don't think that she was the smoothest rower when she first started, but she was incredibly powerful and made boats go fast."

Obviously a fast learner, Miller continued to grow and mature in her sport, spending the next three years in MSU's top boat -- the varsity eight -- and helped the Spartans continue the early success. In 2001 Miller was named Michigan State's first First-Team All-American, as she helped MSU to a third-place finish at Big Ten Championships and a 10th-place finish at the NCAA regatta. She also secured Second-Team All-Big Ten honors. In 2002, she helped MSU to another third-place finish at Big Ten's and earned Second Team All-America honors, while pulling MSU to ninth-place team finish at the NCAA regatta. As a senior, MSU was 11th at NCAAs and finished in a tie for first place at the Big Ten championships -- but took home a second-place team trophy due to the tiebreaker. As a senior, she again earned First Team All-America honors (she was a second-team pick as a junior), completing a three-year run of earning one of the top individual honors in the sport.

The novelty of immediate team success was not something Miller and her teammates concerned themselves with. "To be honest, it isn't something we really focused on as it was happening. We wanted to be the best in the nation and that meant we needed to be willing to do what was necessary to make that happen. I was surrounded by incredible women focused on being the best who were being steered by talented coaches. In our eyes, it was bound to happen!"

Miller holds incredibly fond memories of her time in the Spartan rowing program. "The pride I felt when my family came and supported me at the different races is a big one," she recalls. "I remember Lori Kingstrom singing Eye of the Tiger to me on the starting line as I tried to push the nerves down... Krista Buzzell telling me that she knew we were going to have a good race when she heard me puking at the back of the boat ... How long the run was back to the hotel in Cocoa Beach ... The novices teasing me that I was a grandma as I knitted a scarf while waiting for the athletic trainers to 'fix' me.," she chuckles. "I also received a tremendous amount of support from Bebe, Red, and Matt as I coped with being at school while my mother was sick, and from the whole team when my mother passed away my junior year."

The program has grown over its 20 years -- more All-Americans have been named, Big Ten Championships won, NCAA bids obtained, and even an Olympian have been developed in the boathouse on the Grand River. As MSU's youngest varsity sport, Miller had the opportunity to be a part of many program firsts -- and will now add another to her resume. The program's first First-Team All-American will be the first Michigan State rower enshrined into the University's Athletics Hall of Fame.

"I was overwhelmed and a bit incredulous! It is very special," Miller says of the phone call from Athletic Director Bill Beekman alerting her to her selection to the Hall of Fame. "I have so much respect for the female rowers who paved the way for the varsity program as well as my fellow teammates that I am humbled by the honor to be the first to represent them in the Hall of Fame.

"I have attended several alumni rows and watched as the team has transitioned under Matt's leadership as head coach," she adds. "It is incredible to think about where it all started and where it is today! I am extremely proud of all the women who have shaped and will continue to shape the future of MSU's varsity rowing program."

immy Raye

Football (1964-67)

Fayetteville, North Carolina

Jimmy Raye came to Michigan State from Fayetteville, North Carolina, in 1964 to play football for head coach Duffy Daugherty. When he left MSU in 1968, he left as far more than just a football player. He was a pioneer, trailblazer and barrier-breaker, becoming the first African-American quarterback from the South to win a National Championship, leading the 1966 Spartans to the national title. Now, Raye can add "Michigan State Athletics Hall of Fame member" to his ever-growing collection of roles.

Raye didn't know what to say when MSU Athletic Director Bill Beekman called him to inform him about being a member of the Michigan State Athletics Hall of Fame.

"I was speechless. I was momentarily stunned," Raye said laughing. "It took me awhile to gather my thoughts. I think I said thank you -- I hope I did! It was an exciting euphoria, and I was glad that he made the call."

Raye played on the freshman team in 1964 and was the backup quarterback in 1965 behind starter Steve Juday. As a sophomore, Raye helped the Spartans to not just the Big Ten Conference Championship, but the National Championship as well, playing in the Rose Bowl. In fact, Raye led the `65 Spartans in rushing yards per carry at 8.8 ypc, finishing the season with 192 yards and one TD.

After Juday graduated, Daugherty turned the reins of the vaunted Spartan offense over to Raye in 1966. The junior signal-caller went on to throw for 1,110 yards with 10 TDs, logging a 140.0 passing efficiency rating, which was a school record at the time and still stands as No. 10 on MSU's single-season list. Raye also toted a fierce rushing attack, leading all the Big Ten quarterbacks with 436 yards on 122 carries, adding five rushing scores and earning second-team All-Big Ten honors. With Raye at the helm, the MSU offense amassed 3,549 yards of total offense (354.9 ypg) on the way to a repeat Big Ten and National Championship.

While Raye's MSU career was filled with memorable moments on the field, his favorite memory from his time as a Spartan was as off the field, driving to the Kellogg Center, the team's hotel before home games, with Bubba Smith, the Friday night before the Notre Dame game, aka the "Game of the Century."

"Bubba Smith and I were on our way to Kellogg Center the night before the game as we normally checked in, and we took the long way around. He was driving his new '66 Riviera, and we were cruising up Grand River Avenue and he was waving to everybody outside on the sidewalks that were recognizing us," Raye said.

Throughout that 1966 season, Raye wasn't just recognized as being an MSU football player, but the Spartans' starting quarterback, and was aware of the importance and significance of being an African-American starting quarterback at a Division I school in the 1960s.

"I was aware of it because it was brought up to my attention every day," Raye said. "When I played quarterback at Michigan State, I was the only starting black quarterback in the Division I schools in the United States, and I had been told constantly that I would never play quarterback because that was a position that was considered off basis for a black athlete. So I was aware of it, but it was more about playing than being black. It was certainly brought to my attention on a lot of occasions, starting from being a freshman at Michigan State and during the Championship seasons of '65 and '66."

While it didn't fully hit Raye that he was a pioneer or a trailblazer at the time, he continues to see the importance of that role now in the present and in the future.

"I didn't think of it then, but if you look at college football - the landscape of college football - today, it's very rare to see a Division I school that doesn't have a black quarterback, particularly the good ones," Raye said proudly. "I hope that I served some impetus in helping other youngsters pursue their goals and that the quarterback position wasn't off limits to them, providing they possess the qualities and the skills to play the position. I hope that my playing, particularly as it pertained to integrating Southern schools and maybe, hopefully giving a young man of color the chance to play the position."

Raye's role was brought to the forefront and highlighted in a nationally published book by sportswriter Tom Shanahan "Raye of Light."

"Well initially, I was a little reluctant to do it, but I'm glad I did," Raye said. "As it turns out, I did because it brought to light what a great man Duffy Daugherty was, and John Hannah (MSU President), who was, before I got to Michigan State, was the Chairman of the United States Civil Rights Commission under President Dwight Eisenhower. He and Duffy had a lot to do with giving young men from the Jim Crow South an opportunity to play in the integrated Big Ten Conference and get an education. I think the book highlights that and lets people know that Duffy Daugherty doesn't get enough credit for what he did in the time of civil unrest and a lot of turmoil in this country as it related to equality and equal opportunity, in education and in sports."

Along with his football career, Michigan State instilled several values in Raye that he still utilizes today.

"I learned about having a good work ethic. That you'll face obstacles in your life, but through perseverance and hard work and stick-to-itiveness, this gives you a chance to realize your goals and dreams," Raye said. "That was the case with me because I was just a little black kid out of Fayetteville, North Carolina. What was unique about me getting recruited was I played quarterback at a time when blacks weren't allowed to play quarterback, and even though I went through some excruciatingly difficult times, I survived to play, but not only to play, but be the first black quarterback from the South to make it to the National Championship. That was a very long time ago, and I'm very proud of that fact. I think the lessons that I learned from Duffy and Biggie (Munn) and the whole environment surrounding Michigan State, that denial of opportunity is something that doesn't have to exist and given the opportunity, I was able to excel."

And excel Raye did and Raye has. After his well-decorated successful Spartan career ended following a senior season in which he led the team in passing (580 yards) and ranked third on the team in rushing (247 yards), Raye was drafted by the Los Angeles Rams in the 1968 NFL Draft. He played two seasons in the NFL before joining the coaching ranks, starting back at his alma mater, Michigan State, as an assistant coach from 1971-75 under his own head coach from his playing days, Daugherty, and then Denny Stolz. After one season at Wyoming, Raye returned to the NFL an assistant coach for the San Francisco 49ers in 1975, beginning a tenure in professional football that still continues today. After 37 years as an assistant coach, Raye is now a Senior Consultant in Football Operations in the role of Career Development and Diversity for the National Football League.

"I coached for 37 years in professional football, but I enjoy the job that I have now because it's really not as taxing as the coaching and it allows me to keep my hand in it in terms of minority development, career development for young black coaches and it gives me a chance to stay around the game," Raye said.

Looking back on his time as a Spartan student-athlete, Raye wants people to look back on him not as a football player, but in reference to that of the leader of a marching band.

"I hope when people look back and remember me, it's like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said in his `Drum Major Instinct' sermon, that when people say that I was a drum major for change, that they say I was also a drum major that changed people's minds and made the world a better place because of it," Raye said.

Raye has indeed made the world a better place, being a key figure in the integration of football not just at Michigan State, but across the landscape of college football throughout the country.

Football remains strong and prevalent in his family, as his son, Jimmy Raye III, is Senior Personnel Executive for the Detroit Lions, entering his 24th season in the NFL. Raye's daughter, Robin Michelle Alston, lives in Houston, and he has two grandchildren, granddaughter Avery Alston, who is 12, and grandson Derrick Alston, who is a sophomore forward on the Boise State men's basketball team, and Raye is excited about watching and following his athletic career.

The Spartan great is deeply honored to be inducted into the MSU Athletics Hall of Fame, an accomplishment that Raye humbly recognizes wasn't on his own and is grateful to all the people that helped him.

"There's a number of people I'd like to thank," Raye again proudly said. "My parents obviously, my mom and dad, for having the trust and the belief that I could go that far away from home and leave the segregated South in search of an education and an opportunity. Duffy Daugherty for giving me that opportunity. And all of my teammates that rode that bus, or that train, out of the Jim Crow South in search of equal opportunity or better opportunity for an advancement in education and athletics: Bubba Smith from Beaumont, Texas; Sherman Lewis from Louisville, Kentucky; Earl Lattimer from Dallas, Texas; Gene Washington from La Porte, Texas; Jimmy Summers from Orangeburg, South Carolina; Eric Marshall from Oxford, Mississippi; Ernie Pasteur from Beaufort, North Carolina; Charlie "Mad Dog" Thornhill from Roanoke, Virginia; Jimmy Garrett from Columbia, South Carolina. And so many others that were able to persevere and succeed out of the Jim Crow South and hopefully the things that we did and accomplished, that they had a change in the way some people think and that we made the world a better place."

Raye has had many roles and titles along the way to making the world a better place, and from now on, will proudly do so as a Michigan State Athletics Hall of Famer.

Bill Wehrwein

Track & Field (1967-1970)

Roseville, Michigan

Sometimes a few words of encouragement are all it takes to launch a Hall of Fame career. Track and field national champion and All-American Bill Wehrwein heeded several careful words that took him far in his Michigan State career and beyond.

Former Major League Baseball manager Sparky Anderson and former MSU track and field head coach Jim Bibbs both provided vital words of wisdom that followed him throughout his career on and off the track.

"Sparky Anderson once said `miss no opportunity so say something good to a kid.' That almost became my motto. He and Jimmy Bibbs really knew how to motivate people. I learned from Jimmy and Sparky Anderson, and I think those two little lines were almost like a daily ritual in my mind," said Wehrwein said.

Years after his time on the track at Michigan State, the runner was surprised when he was informed that he would be the latest in a long line of MSU athletes to enter into the Hall of Fame.

`'It was quite a surprise. I really never thought that I would get this far. I am kind of humbled because I really felt like we were thinking of some of the great athletes from the past that are in the Hall of Fame, and some that aren't, and it is quite an honor and quite a shock," Wehrwein said. "I talked to one of my teammates, like Gene Washington, and he told me that Jimmy Raye was going in, and Jimmy Raye is a legend in my mind. It really just gives me the chills. I just really have to say thanks to all my great teammates."

As a three-year varsity letterwinner from 1968 to 1970, Wehrwein was a four-time All-American. He won five Big Ten titles, including four as an individual.

"That particular period that I was running was probably the greatest period of MSU track and field. It saw guys like Washington, Bob Steele, Clinton Jones, Mike Bowers, Roland Carter -- all these people who were so great. It was really something, a special time to be a part of that team," Wehrwein added.

The 1969 outdoor season was bountiful for Wehrwein. His efforts that season helped guide the Spartan men to a third-place finish at the Big Ten Championship in West Lafayette, Indiana. He was part of the relay team that finished second in the mile relay at the B1G Championship. In addition, he went on to win the NCAA Indoor title in the 600 at nearby Cobo Arena in Detroit.

He still holds the Big Ten indoor record in the 500-meter run also set during the 1969 season. Wehrwein broke the American record in the 600-yard run with a time of 1:08.6 as a sophomore. The time was set at a familiar track in East Lansing, on the dirt track at Jenison Field House.

That same year, he was the 1969 U.S. Track and Field Federation National Champion in the 600-yard run. While running at MSU, he also broke records in the 300-yard and 440-yard runs.

As a senior in 1970, the Big Ten Indoor Championships were held at MSU's Jenison Field House. The last event of the day was the mile relay, and it just happened to be one of the few times that Wehrwein's father was able to watch him compete. The rest of the relay team -Michael Murphy, John Mock and Al Henderson - kept the Spartans within distance before Wehrwein's turn was up.

"They kept it close enough that I was 12 yards behind the world record holder in the 1,000 yards (Marc Winzenried from Wisconsin) and next to him was the Big Ten champ in 440. I was just so psyched up that I don't think anyone in the world could have beaten me in that moment," Wehrwein. "When I finished the race our athletic trainer Clint Thompson said, `I don't know what is more wonderful to watch, you running so well or your dad hanging over the railing screaming his head off.' It is one of those moments that I heavily cherish."

Wehrwein is well aware of all the people who helped him reach his potential at MSU. Several coaches and staff helped him become a world class runner.

"I just really want to thank my high school track coach Max Berry. In a way, I'd like to thank my baseball coach from little league who said I was too slow to play centerfield. You get tired of hearing these opinions. It makes you want to go to a sport where you cross the finish line first, and they can't say the guy in third looked faster so he is going to get the medal. Coach Bibbs was such a motivator. He called everyone on the team champ. When he first came there he'd say, `how ya doing champ.' It was just a cool motivator. He had a way of saying great positive things to everybody," he said.

It takes a small army to keep any athlete healthy. Wehrwein attributes much of his success to the athletic training staff at MSU, which was led by Thompson, the Hall of Fame athletic trainer.

"Clint Thompson was a big, big, big influence on me not only for his athletic training ability, but he was also a spiritual guy that really helped a lot of us. I don't think that I would have made it through four years without him. He was special," Wehrwein added.

The phrase Spartan Family holds a very deep meaning for Wehrwein as well, as names like MSU Athletic Director Clarence "Biggie Munn" were always around the track and field program.

"He came to all the meets; he was a track guy. He was a Big Ten Champion in track. He was something else. He paid attention to us and called us into his office after meets and congratulated us. He wasn't just a figurehead or someone who just paid attention to the revenue sports. Biggie was special and really motivated the troops," Wehrwein added.

After graduating from Michigan State, Wehrwein remained in the field of education as a teacher. The physical education teacher worked with the Kellogg Foundation to establish the Feeling Good program, working to educate children and parents on the importance of nutrition and exercise.

Track and field was not out of his system though as he went on to coach his own children in middle school. In order to spend more time with his kids, he coached little league baseball as well as track and field. In doing so, he looked to pass along some of the wonderful that he was given as a young athlete, sparking what turned out to be a Hall of Fame career.

Want the latest breaking MSU news delivered straight to your email for FREE? Sign up for the DAILY Spartan Nation newsletterWHEN YOU CLICK RIGHT HERE!Don’t miss any of the latest up to the second updates on Michigan State Sports when you follow on Twitter @HondoCarpenter