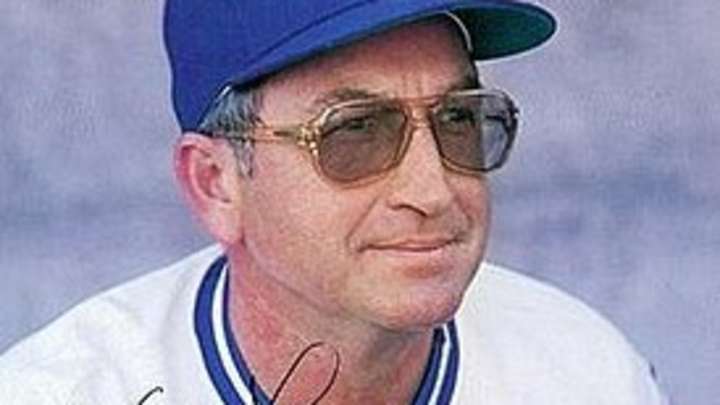

Jim Frey Helped Make Cubs Relevant When They Needed It.

The first time I thought about Jim Frey was in spring training in 1984, his first season as Cubs manager.

The Cubs had been managed in 1983 by Lee Elia, best known for his now-amusing profanity-laced tirade against unforgiving fans: ``the blankety-blank 15 percent who come out to day baseball while the other 85 percent are earning a living.’’ Don't play it around people who might be offended. But it's still pretty fun, if you like that sort of thing.

The Cubs had been messy since the Santo-Williams-Banks-Fergie team faded in the early ’70s. They still had not made a post-season appearance since 1945. Even that came with the World War II asterisk.

And so, when Frey told the world in that spring training of 1984 that he thought this team could be a powerhouse, I thought he was. . . a cockeyed optimist. Among other things.

It turned out, though, that he was right. That Cubs team had a lot of bats. And when it traded for Rick Sutcliffe at mid-season, it had a pretty good set of arms.

Frey, who died this week at 88, had managed the Kansas City Royals to the 1980 American League pennant before coming up short in the World Series against the Phillies. And in 1984, Frey would manage the Cubs to their first post-season appearance in 39 years before coming up short in the National League championship series against the Padres.

General manager Dallas Green was on a mission to shed the Cubs' image as lovable losers. And Frey was instrumental in helping him do that.

That loss to San Diego was especially painful because the Cubs won the first two games in Chicago before going to San Diego, where they only needed to win one more game to capture the best-of-five series.

The mitigating circumstances: First, there was a post-season umpires strike for the first four games. This was especially painful, I thought, for hitters like Cubs outfielder Gary Matthews, who were famous for not swinging at pitches outside the strike zone. I don’t want to make too much of this, because San Diego also was loaded with veteran hitters who knew their way around the strike zone. But it's sort of like playing a football game in the rain. It's the same for both teams. But it's not ideal.

Second, the Padres were cool as the proverbial cucumbers. And by the time Game 5 came around, the Cubs were nervous nellies. I was doing the Padres’ side of things for the Chicago Sun-Times in that series. And two things stick out.

After the Cubs won Game 2 to complete their two-game sweep in Chicago, I hung back in the tiny visiting manager’s room at Wrigley Field with Dick Williams, who began to eat visiting clubhouse spaghetti.

He looked up at me and asked if there was something else, if I had another question.

I said something about being surprised he was sitting there eating spaghetti after going down 2 games to none.

He said something like, ``What do you want me to do?’’ and went back to his spaghetti.

Contrast that with Sunday morning in San Diego before Game 5. We were sitting in the dugout with Jim Frey. He was whiter than the baseball. To this day, friends remind me that I called them before the game to tell them that.

Then Leon Durham let a ball go between his legs with his Gatorade-soaked glove, courtesy of a dugout mishap. Some people attribute that to the Curse of the Billy Goat. I don't agree. I played on the Sun-Times softball team, sponsored by the goat's owner, the Billy Goat Tavern. Didn't stop us from winning championships.

I would just file the Durham gaffe under. . . Stuff happens. To the Cubs.

For all the disappointment, Frey was the manager when the Cubs became good enough to break our hearts again.

He showed Ryne Sandberg how to become a dangerous power hitter.

Frey's weakness, as both a manager and later as the Cubs’ GM, was a fondness for the three-run homer at the expense of other things. This was a concept he learned from his mentor, legendary Baltimore manager Earl Weaver. That’s what baseball observers far more knowledgeable than me say. I will defer to them.

One thing I really liked about Frey, though, was his wry sense of humor.

``It never rains at the ballpark. It only mists,’’ he used to say.

Another droll gem: One hot summer Saturday afternoon, his old boss Earl Weaver was in town as part of a national broadcasting crew. The game had been a tumultuous one in which both teams used every available player. Outfielder Thad Bosley had finished the game at shortstop for the Cubs. Bosley also had had a big day at the plate.

When we went into Frey’s office after the game, he and Earl were sitting there, pulling on 16-ounce cans of Budweiser.

The AP writer, a crusty part-timer, excitedly said to Frey: ``What are you going to do with Bosley?’’

Frey looked over at Earl and said, ``He’s my new friggin’ shortstop.’’ They both laughed. So Frey said it a couple more times.

My favorite, though, was a story Frey told about managing in the minors. A street-tough player who was barely clinging to a roster spot came in to see him and said, ``If you cut me. . . I cut you.’’

R.I.P., Jim Frey. You didn’t win it all. But you made the Cubs relevant again at a time when they needed it. And 1984 was a very fun ride for a very long time.

@@@

If you like sports history with an extra bit of drama, please check out my 1908 Cubs novel, The Run Don’t Count. Excerpts and other information at facebook/therundontcount. It’s available in paperback and Kindle at Amazon.com.