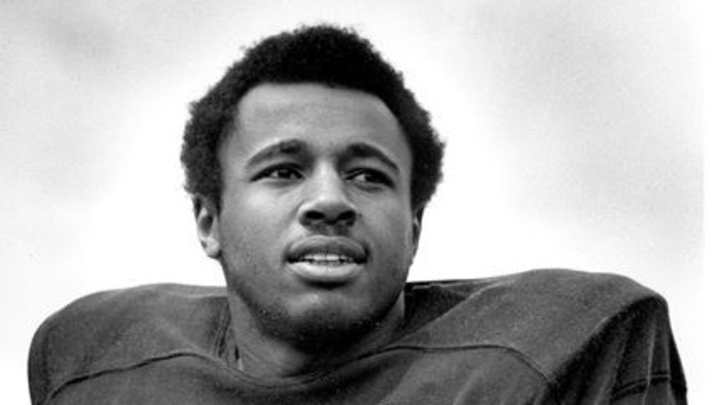

Calvin Jones (1951-2021) Was UW's First All-American Corner, Social Crusader

Calvin Jones stood all of 5-foot-7, if that, but he was tall enough to fend for himself on the University of Washington football team. He was brave enough to stand up to just about anyone, including the school.

Just ask Dan Fouts.

Oregon quarterback legend. NFL Hall of Famer. Empty-handed Husky Stadium visitor.

In 1972, Fouts drove his team to a first down on the UW 10 in the closing moments of a spirited game in which the Ducks trailed 23-17. Three times, Fouts went after Jones with bullet-like end-zone passes. Three times, the defensive back leaped up and swatted the ball away, his final deflection ending this memorable duel on fourth down with just 12 seconds remaining.

Jones, always so electrifying and enigmatic, was the UW's first All-American cornerback. He became an accomplished NFL player and later a minister in his hometown of San Francisco. He also was a social-injustice crusader who was ahead of his time.

This Husky trend-setter recently died at age 70, the school revealed on Thursday after being notified by his family.

Jones showed up at the UW as a part of the swashbuckling Sonny Sixkiller era in 1970-72, as someone who stood out on defense as much if not more than the other guy did running the offense.

Similar in stature, both were intoxicating personalities and fearless competitors for the Huskies, especially in the heat of the battle.

"No matter what, he always had a great attitude; it was a winning attitude," Sixkiller said. "It permeated our defense. Our defensive guys were rough and tough, knock your head off, and there's Calvin, smiling away and being a part of it."

California wide receiver Steve Sweeney, who at 6-foot-4 held a nine-inch height advantage over Jones, had fearsome battles with him downfield, but he couldn't match this Husky cover guy for words.

"I just feel he has too big of a mouth for as little as he is," Sweeney said in a post-game interview. "He keeps talking to you during the game."

Jones was a three-time All-Pac-8 selection, enough of a defensive nuisance to come up with 11 career interceptions. He turned one pass theft into a 66-yard score against USC in Los Angeles.

Also a highly elusive punt returner, he scored on a 78-yard runback at Cal and a 57-yarder against Illinois in Husky Stadium.

The Associated Press, the ultimate standard for postseason honors, named Jones as a first-team All-American following his final season in 1972. UW safeties Al Worley (1968) and Tom Greenlee (1966) previously had received this coveted AP accolade as secondary players, but Jones was the first Husky corner so honored.

Much more importantly, Jones was able to use his football stature as a social platform — he forced the hand of the UW to finally address racial inequalities that were rampant throughout the athletic department.

At the end of the 1970 season, the confident defensive back and three African-American teammates, running back Mark Wheeler, wide receiver Ira Hammon and tight end Charles Evans, stunned the city by holding a news conference and citing a long list of grievances. Wheeler had quit during the season. Jones and the others walked away from the team on the spot.

The players' abrupt departure left the UW with an all-white roster in supposedly culturally enlightened Seattle, something that existed elsewhere in college football only at the University of Mississippi.

For the next 10 months, the Husky athletic department leaders and Jim Owens' football coaching staff did everything they could to entice Jones — who attended Long Beach City College in his absence and planned to enroll and play at Long Beach State — to return to the UW in 1971.

As a result, the school hired a black assistant athletic director, plus African American assistant football and basketball coaches, and made other societal concessions. That was enough to bring him back.

Jones expressed no regret over his strong-armed tactics. If the Huskies wanted him as this superlative athlete to play football for them, he was adamant changes were going to be made.

"I think it helped me as a person, helped me to find what my attitudes were, my relations in dealing with white people and my relationships with football, and what it actually meant to me," he said of the stand he took.

Teammates remember Jones as someone who could dunk a basketball, but he couldn't shoot one. He was the guy who impishly would jump offside just to knock a receiver off his feet and send a message.

He could be a fun entertainer, too, mesmerizing Sixkiller and the rest of the Huskies at a team talent show by sitting down at a piano and belting out the popular song "Lean on Me" by the late Bill Withers. This all seemed so apropos because these players depended so much on their compact cornerback.

Years later, Sixkiller told how he enjoyed that performance so much he convinced Jones to sing it again when they got together with their wives and had a night out.

Lean on Me.

Done with the UW, Jones went to the Denver Broncos as a 15th-round draft pick, someone deemed unlikely to make that NFL roster because of his size. Yet he started in 44 games over four seasons before injuries took a toll and sent him into pro football retirement.

Always a playmaker, he finished with 12 interceptions for the Broncos and returned a fumble 43 yards for a touchdown against the Cleveland Browns in 1976, his final pro season.

Jones was such a well-known football player and a spiritual presence, he was invited to speak at the Billy Graham Crusade to open Seattle's Kingdome, also in 1976. Seven years later, the UW voted him into its athletic hall of fame.

When his football days were over, Jones attended Harvard University's Divinity School and became pastor of Providence Baptist Church in San Francisco, succeeding his father. People were depending on him to the end.

"When we heard of Calvin's passing," Sixkiller said, "both my wife and I go 'Lean on Me,' we'll never forget it."

Go to si.com/college/washington to read the latest Husky Maven stories as soon as they’re published.

Find Husky Maven on Facebook by searching: Husky Maven/Sports Illustrated

Follow Dan Raley of Husky Maven on Twitter: @DanRaley1 and @HuskyMaven