Love the NFL's high-tech tricks? Early innovators put the ball in play

As you sit back and watch the Super Bowl this Sunday, before you start waxing to your friends about the good old days, and old-time football, and before you start complaining about how the game has become too wired in to technology, with all the video reviews, and all the shots of coaches showing players digital images on the sidelines, understand, very few of these innovations are new, they’ve just been refined and perfected over the years.

- Super Bowl XLIX: News, features | Complete coverage of Deflategate

Joe Horrigan, the executive vice president of museums, selection process and chief communications officer at the Pro Football Hall of Fame, has some good stories to share, to illustrate just how many of the high-tech things you see during a typical NFL game have roots that go back to the days before players even wore face masks.

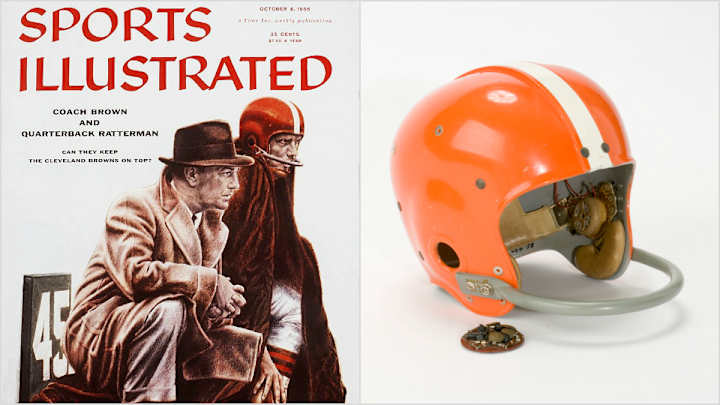

“Take Paul Brown, for example,” Horrigan said earlier this week from Phoenix, where he’s set to watch the big game. “He was not only an innovative coach with the X’s and O’s. In 1956, Brown was using coach-to-quarterback communication systems in helmets.”

The story behind Marshawn Lynch’s unique high-altitude training mask

Horrigan recounts how Brown was approached by a couple of inventors in Cleveland who told him they could put a radio receiver inside the quarterback’s helmet. Brown was all-in.

“This was at a time when transistor radios were considered really neat,” Horrigan says with a laugh. “And these guys had a radio receiver they wanted to show Brown. The coach listened, which was probably more than the rest of the sporting world would’ve done.”

The inventors built a prototype for Browns quarterback George Ratterman, then went to testing.

“One day, the inventors wanted see what the range was for the device,” Horrigan says. “So one of the two inventors got into his car and started heading off in one direction while the other stayed at the home base. The receiver started picking up police calls. And the policemen were picking up the inventor’s calls. So, ultimately, a strange guy in a football helmet got pulled over. When he explained what he was doing for the Browns, he asked the cop to keep the secret.”

So secretive was the coach about the project that, when he finally put it to use in preseason games, he would hide on the sidelines as he would call in the play.

“It took a few games before the team on the other side picked up that something was happening,” Horrigan says. “And finally, around the third game, they were exposed. So the other team, the St. Louis Cardinals, was instructed to smack the helmet around when they had the chance. They didn’t know what was going on, but they knew something was up.”

Horrigan says that a couple of teams soon tried to come up with their own answers to this system before Bert Bell, the commissioner, declared the devices illegal.

“Bell said that the only receiver in pro football was going to be a wide receiver," says Horrigan. "It wasn’t until much later that the idea was resurrected and became a part of the modern game. Basically, it was an early innovation that came from Brown clandestinely trying to get an edge.”

Not all of Brown’s ideas were good ones. In fact, one of the bad ideas was so bad that its failure may have kept Brown from having to deal with a potential equivalent to the Deflategate scandal.

“Someone came to him with an idea, a guy from Akron, Ohio,” Horrigan says. “He told Brown he had a way to solve the problem of the ball getting slippery. He showed him two different versions of a ball heater. They were cast iron heaters that needed to be plugged in on the sideline and they looked like World War II unexploded mines. Big, ugly, gray, about two feet ball.”

The lid to the heater would flip open and inside it were rotating heating elements. Someone would place the ball in on its point and the ball would turn around as the heaters dried the ball.

“They had a single-ball and a double-ball heater,”Horrigan says. “Brown used it in a preseason game and the first player to have one of the heated balls nearly broke his foot when he punted it. Not only did it dry the ball, it baked them, turned them into rocks. It was a short-lived idea.”

Horrigan likes to tell the stories because they illustrate how Brown was a great thinker, a great teacher, and a visionary when it came to the different ways in which technology could change the game.

The story behind football's innovative yellow first down line

“He was one of the first coaches who brought the classroom into football,” Horrigan says. “He believed in new and innovative ideas and he certainly believed in trying to find a competitive edge. Today, there’s a misconception that there was never a movement to improve the game through equipment and technology, but that couldn’t be further from the truth.”

And with that statement, Horrigan has one more story to illustrate his point.

“When Polaroid cameras were new,” Horrigan says. “Wellington Mara, whose father owned the Giants, sat up in a catwalk at the top of Yankee Stadium, sending down pictures in a weighted sock, down a cable to the field, so he could show what the opponent’s formation looked like.”

So, when an official’s call is reversed this Sunday, because a high-definition replay shows a receiver’s foot was one inch out of bounds, or if one team makes an adjustment based on something the computer prints out from the press box, understand, while these types of things have been perfected, there were men plotting just such devices way back in the day.