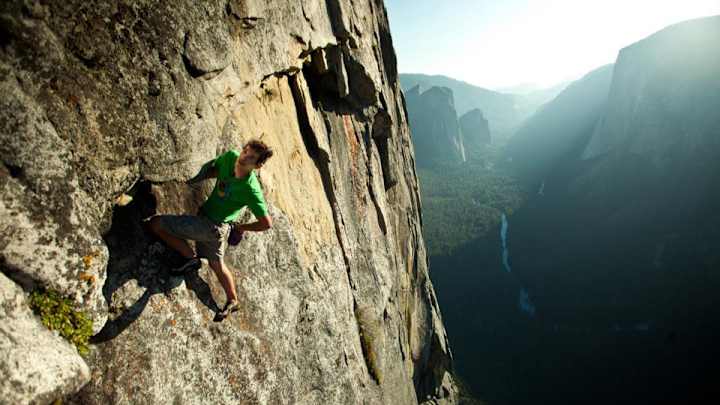

Valley Uprising documentary shows the extreme rock climbing revolution

On January 14, 2015, in the fading sunlight of a clear California afternoon, Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson achieved a feat that many had deemed impossible. After 19 days, the duo completed the first free ascent of El Capitan’s Dawn Wall—the most difficult route up the 3,000-foot granite monolith in Yosemite National Park. Upon reaching the summit, Caldwell and Jorgeson embraced their family members. They celebrated. They sprayed sparkling wine.

Their achievement further confirmed Yosemite’s standing as the mecca of rock climbing.

Life on the Edge: Dean Potter Opens Up About His Daredevil Secrets

“All the standards of rock climbing have been set in Yosemite,” Caldwell said last week from his home in Estes Park, Colo. “It’s the center of the universe for big wall climbing.”

Valley Uprising, a 90-minute documentary by Sender Films, captures the history and evolution of rock climbing at the National Park in the Sierra Mountains, 200 miles east of San Francisco. Co-directors Nick Rosen and Pete Mortimer spent seven years and interviewed over 50 living climbing legends to bring to life the counterculture, rebellion and innovation that have defined and redefined climbing at Yosemite for the past 60 years.

The documentary will air on the Discovery Channel on April 25 at 8 p.m. ET/PT.

"Valley Uprising will take viewers to places of tremendous natural beauty they will otherwise never experience in their lifetime," said John Hoffman, executive vice president, documentaries and specials. "This extraordinary film tells the story of how Yosemite became ground zero for generations of rock climbers and the proving grounds for the sport's elite.”

Climbers complete free-climb ascent of El Capitan's 'Dawn Wall'

The film focuses on three specific generations of the climbing movement at Yosemite. First, the Golden Age, defined by Royal Robbins and Warren Harding’s 14-year duel to outdo each other.

“We got hooked quite frankly by the adrenaline of it,” said Robbins, who became the first American climbing icon after he completed a five-day ascent of the 2,000 ft. Northwest Face of Half Dome in 1957.

A rivalry emerged after Harding set his sights the biggest wall in the valley, El Capitan, 1,000 feet taller than Half Dome. Instead making the climb in a single push, Harding opted to use fixed lines and nylon ladders that allowed him to make several trips from the base of the valley. He finally summited the central prowl on El Cap, dubbed The Nose, after 18 months.

The tension culminated in 1970, when Harding along with Dean Caldwell attempted to ascend the Dawn Wall. After 28 days, over 300 bolts, torrential storms and repeated called off rescue efforts, Harding and Caldwell reached the top and were greeted by dozens of reporters.

The next wave of climbers, known as the Stone Masters (1973–80) and led by Jim Birdwell and a host of other Camp 4 climbers, introduced a new athleticism to the sport and popularized free climbing, where one only uses their hands and feet on the rock to make upward progress. Equipment is only utilized to prevent a fall.

“We wanted to set new standards,” said Lynn Hill, who made the first free ascent of The Nose on El Capitan in 1993.

Yosemite’s most recent crop of climbers, The Stone Monkeys, have carried on that lineage and have continued to push the boundaries of what’s considered possible or even sane.

The summit is no longer the destination. Now it’s the beginning.

“I consider myself a rock climber but the definition of rock climbing as has changed,” says Dean Potter, one of the leaders for the Stone Monkeys.

Besides free soloing—climbing without the aid of any gear—Potter is known for his BASE Jumping and highlining, or tightrope walking at high elevations with no tether.

Potter and the Stone Monkeys’ pursuit for innovation doesn’t arise from an absence of fear but rather its presence.

“All of us that do what we do struggle with fear at beyond level,” Potter says. “The knowledge that in a split second that I could be dead almost overwhelms me. But it is through constant exposure to that fear that keeps me alive and lets me do what I love.”

Not everyone is thrilled.

This past November, Clif Bar, the energy bar company and a sponsor of Valley Uprising, dropped its backing for five climbers profiled in the film, including Potter and Alex Honnold.

It wasn’t the first time Potter’s “dangerous arts” clashed with his sponsors’ interests. Patagonia withdrew their support for Potter in May of 2006 after he received criticism for free soloing the Delicate Arch—a 65-foot sandstone structure in Utah’s Arches National Park.

“When you do things that are different and extreme, some people like it and some people don’t,” Potter said. “I don’t really care if I am liked or not liked.”

Not your ordinary workout: Climbing the Great Wall of China

Clif Bar’s decision highlighted the clash between climbing’s rebellious roots and counterculture ethic versus the sport’s increasing popularity and media coverage.

The collision of the two worlds was evident during Caldwell and Jorgeson’s effort to free climb the Dawn Wall that Harding ascended 45 years prior.

“Yosemite is where my heart is,” Caldwell said. “I feel like climbing is this incredibly positive way to live. It satisfies this primal need to battle and seek adventure. Climbing is this incredible life driving force that creates these beautiful challenges and makes my life so rewarding.”

After he summited the Dawn Wall, Caldwell fielded countless interviews. He let his battered fingers heal. He played with Fitz. But on January 21, he posted a picture on Facebook from the top of El Capitan.

“I started to go a little crazy,” he said with a laugh when asked why he didn’t take a longer break. “I need climbing like I need water.”