Duct Tape Invitational: Recapturing the grace of longboard surfing

At the U.S. Open of Surfing in Huntington Beach, Calif., the Pacific Ocean at times looked more like Lake Erie.

During the Pro Junior final on Saturday, surfers often had to resort to stomping up and down on their wafer-thin shortboards to generate momentum and extend their rides on the lackluster waves. The maneuver is so common in contests at the iconic Southern California beach break that it has entered the surfing vernacular. It’s called the Huntington Hop.

“Your feet start to hurt,” said Kanoa Igarashi, a 17-year-old from Huntington Beach who took second place in the Pro Junior final.

But the four competitors in the last heat on Saturday afternoon didn’t have to worry about hopping or the high tide conditions.

They had the perfect equipment.

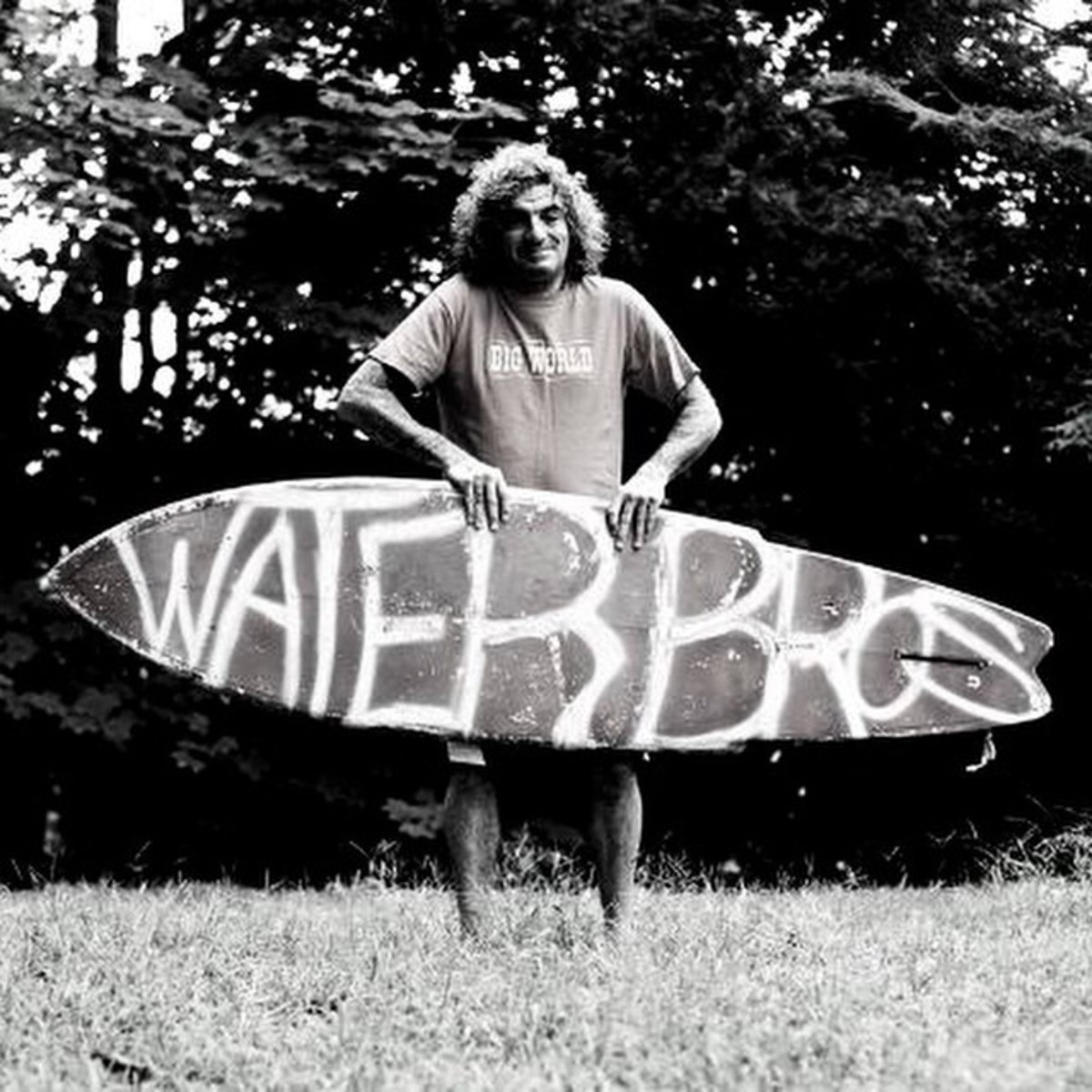

“Longboarding is so much more fun than having to try to generate your own speed in small waves,” said Justin Quintal, one of the finalists in the Joel Tudor Duct Tape Invitational.

The Greatest Wave: Greg Long's near-death experience changed everything

Joel Tudor, the event’s namesake and originator, is often regarded as the pinnacle of style in longboard surfing. He won the U.S. Open of Longboarding nine times, including six in a row from 1995 through 2000.

Despite the success, Tudor grew increasingly dissatisfied with the direction of the sport and the “high performance” movement that emerged in the 1990s and early 2000s. Instead of using the classic nose-riding style of the 1960s and ’70s, longboarders began trying to imitate their shortboard counterparts. That desire to fit in resulted in lighter, thinner boards meant to pull off sharper turns, and blurred the distinction between the two forms of surfing.

“During the high performance movement, longboards were just like big shortboards,” Quintal said. “It lost the identity of what longboarding was really about. Joel has ushered in traditional surfing again and it [the DTI] is meant to show people what good longboard style is.”

Tudor triggered the revival when he selected 16 of the world’s best longboarders to participate in the first DTI at the East Coast Surfing Championships in 2010. The event has spread across the world to such spots as Biarritz, France, Nova Scotia and Noosa Beach in Queensland, Australia. This year’s contest at the U.S. Open was the 11th DTI and the third at Huntington Beach .

At all the venues, the invitees have to ride single-fin boards that are at least nine feet in length, known as “logs.” The boards must also weigh at least 12 pounds, have smooth rails, and no leashes or leash plugs. The regulations are meant to preserve and showcase longboarding’s roots.

“Its kind of a lifestyle choice if you are into these boards or not,” Tudor said while commentating on the DTI final. “It’s a tradition we want to keep alive. We [longboarders] were the beginning of the US Open when the event started in the ’60s.”

The contrasts between the DTI and other surfing contests at the U.S. Open extend beyond the riders’ gear.

Twice perfect: Owen Wright makes surfing history at Cloudbreak in Fiji

While most shortboard competitions feature priority, which means one surfer at a time has the unconditional right of way to catch any wave, the invitational is more democratic. There are no interference rules, and the longboarders rely on “gentleman’s priority.” Sharing waves is encouraged. A $500 bonus was awarded for the best two-man wave ridden in each heat and a $1,000 bonus was up for grabs for best shared wave in the final.

“It’s a pretty loose format,” Quintal said. “It’s pretty cool because it keeps you honest in the way you surf and you are never going to see somebody paddle battling. There is always a positive energy.”

Quintal, 25, a goofy footer with long brown hair and a Castaway beard, learned to surf when he was three, in the small waves of Florida and South Carolina, but did not start longboarding until he was 11.

Today, Quintal “rides everything” so he can surf all variety of waves. He has earned a reputation as one of the current generation’s top longboard talents. He won the second-ever DTI in October 2010 in Montauk, N.Y., and claimed first at Huntington Beach the past two years. Yet, due to the lack of prize money and opportunities, longboarders can’t depend solely on contest results to earn a living. To support his career, Quintal travels the globe, searching for waves to film video segments and get photos for magazine features.

The financial gap between the two types of surfing was apparent this weekend.

On Sunday, Hiroto Ohara received a $100,000 check (the richest prize in all of surfing) for winning the World Surf League QS 10,000 event. The prize for first at the invitational was $4,000, plus a surfboard shaped by Tudor.

“I don't think the public understands longboarding, and if they did they would fall in love with it, like I have,” said Karina Rozunko, a first-time invitee to the DTI.

Rozunko, who hails from San Clemente, Calif., rides both short and longboards like most of the surfers in the DTI, but she prefers the latter.

A Day in the Life: Professional surfer Ian Walsh

“I gravitated toward longboarding, because I like the more relaxed vibe,” she said. “Shortboard surfing kind of attacks the wave and I prefer the graceful glide of longboarding that works with the wave. The feeling of gliding on a longboard is unlike anything else. To me it feels like a dance with nature.”

During the DTI Final, Quintal’s footwork was as smooth and graceful as a ballroom dancer's. On his third wave he sidestepped to the front of his board, turned, and then hung his heels over the nose.

“I don’t really have any strategy,” Quintal admitted before the contest. “I just want to surf how I normally do and my main thing is to find some good waves, pick the right line, and ride it the best I can. Hopefully the scores will reflect that.”

They did. Quintal’s “Heel 10” earned him a 9.57. But Tommy Witt, another longboarder from San Clemente, kept the heat close with a blend of classic and innovative moves. On one of his two scoring rides, he paddled into the wave with his board turned backwards then flipped it around like a skateboard shove-it.

It wasn’t enough, though, to dethrone Quintal, who won his third consecutive DTI.

When the final horn sounded, Witt didn’t sulk like Kanoa Igarashi after his narrow loss to Griffin Colapinto in the Pro Junior Final. Instead, Witt paddled over to Quintal and congratulated him. The two shook hands and fist bumped. The other finalists, Troy Motherhead and Kai Ellice-Flint, joined in.

Motherhead leapt off his board and did a cannonball—splashing Quintal. All four exchanged high-fives, then headed back to the shoreline.

They shared the wave.