Nike knocks out a new custom boxing boot for Olympian Marlen Esparza

At first U.S. Olympic boxing medalist Marlen Esparza wasn’t all that excited about her meeting at Nike to discuss boxing boots. But then Tobie Hatfield happened. The 25-year veteran of Nike creative design—he created Nike Free—decided to take on Esparza’s personal project, creating a women’s boot designed specifically for her. With her.

That transformed Esparza’s excitement level.

To this day there’s no such thing as a women’s boxing boot. Esparza, 26, the flyweight bronze medalist at the 2012 London Games, tells SI.com that, as a women's size six, she has always ordered in men’s sizes, giving her boots—even when sized down—way too much wiggle room. “They never fit correctly,” she says. “Too wide, too tight at the ankle. I’d adjust with double socks and learn how to get used to it. Feet and hands are the most important thing, so shoes and gloves are really the most important equipment.” Esparza wanted to finally get the shoe part right.

***

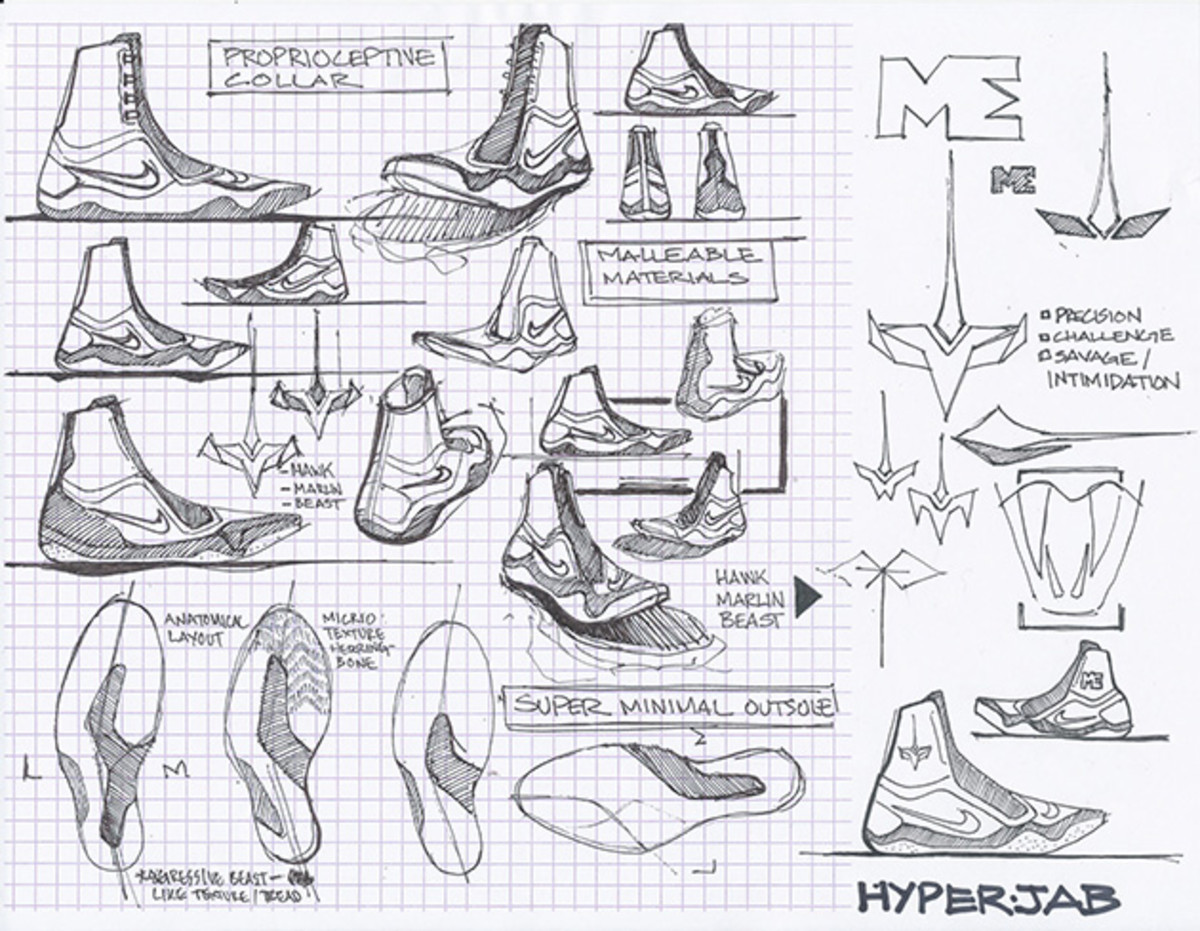

Hatfield works in Nike’s Innovation Kitchen, a high-level design studio on the company’s Oregon campus that allows one of Nike’s most famed employees to work on specialty projects. Sure, creating a women’s boxing boot—now dubbed the HyperJab—won’t sell millions of units to the masses, but it could help Esparza win a gold medal in Rio de Janeiro next summer. And it could help craft the next change in any number of products. Hatfield tells SI.com that he wants a part of that, both helping Esparza and finding future solutions.

Once Esparza sat down and started explaining what she needed—a higher and more protective collar, a different construction to keep the boot secure on her toes, better fit for her foot shape, enhanced grip, lighter materials, etc.—Hatfield reached into his memory, pulling ideas and tools from past creations, such as a wrestling shoe that he had helped create.

“We don’t have to recreate the wheel and start literally from scratch,” he says. “There are tools all over the place. That is the recipe. It is like a chef thing. I started with the stock and she’s the one who told me how to enhance the flavors.”

For Esparza, once she realized all the issues she was having with her boot, she didn’t let up. For example, to address the problem of the front of the boot tearing away as Marlen slid across the canvas, Hatfield created a new grip that extends higher than before. To deal with the fit, he molded the boot to Esparza's foot, creating an asymmetrical shape to better fit with her on-canvas motions and moved the lacing to the side of the boot to allow for more support during movement.

Then there was the material. Hatfield brought in meshes, TPU skins, foam and a new interior lining to help with everything from ensuring that Esparza didn’t get blisters on the back of her feet when she wore no-show socks to building the lightest boxing boot Esparza had ever seen, still with support.

“The first time I walked in [to a gym], everyone was instantly, ‘Where did you get those? How did you get those?’” Esparza says. She was laughing at the boys, as they were now begging to know if they could get her prototype shoes in men’s sizes, even if it was in the pink or gold (Esparza is “obsessed with gold”) Hatfield had made to match her personality. For the first time in her life, she didn’t need a men’s size. And the men were out of luck.

“I have to stop training so people can ask to see my shoe,” she says. “It is not a normal boxing boot. When people see the boot they know it is a completely different type of boxing boot all the way around. I get 100 million and one compliments.”

Esparza was over the moon with her new boot, but she also got something that ratcheted up her excitement level. Hatfield made her a personalized logo.

When Esparza started talking about her boxing style and what a boot meant, she spoke about how she attacks and moves a lot, which gave her the nickname the “beast.” She spoke of how her name, even from a young age, always drew comparisons to a marlin fish and how her punches hurt more because people don’t see them coming, like a hawk. “It is the punches you don’t see coming that are the ones that hurt,” she says. When Esparza came back with her specialized boot, complete with her own logo on the side, it was then that it all struck her.

“I didn’t realize how big of a deal it was going to be for me,” she says. “It was surreal. I was going so long in something that didn’t help my performance to something that almost makes it perfect.”

***

Hatfield, 55, likes the title of “innovator.” That’s what he enjoys most; that is what he identifies with. The brother of famed Jordan designer Tinker Hatfield, Tobie came to Nike through a different route, not through the typical design channels as his architect brother.

Tech Talk: Inside the world of sports’ most popular insole, Superfeet

Hatfield, a former track and field athlete, started in the materials department in 1990, when only four people worked in that area of Nike. “I didn’t know a polymer from a foam from a fiber, it was all on-the-job training,” he says. “Once I had that education, I was able to explore and put my athleticism with my new knowledge and combine that.”

He went from materials to developing to understanding the manufacturing process in Asia to engineering and even research and development. Hatfield understood it all and he says it combines to make him “a friend to the athlete,” such as in the way he was able to take Esparza’s negative experience and turn it into gold. Or how he created Nike Free to fit a need. Or his part in crafting Flyknit. Or the skeleton spike he created for the 2002 Winter Olympics.

By working on so many specialty projects, Hatfield takes his understanding of materials, engineering and production and melds them together. “If I’m just in one pigeon-holed area it narrows you down way too much,” he says. “I’m a better friend to the athlete if I can be free to roam.”

Special projects have taken on a new life at Nike. In the early days, Hatfield says, he would work on 40 to 50 different projects at any one time, ranging from materials and apparel to shoes. Now, with 100 employees working on R&D in just footwear, the company has 300 projects going at a time, most never seeing the light of day.

“Innovation is failing forward, failing more than you succeed,” he says. “I love the idea of the Innovation Kitchen. We are putting in ingredients, taste testing and stirring and sometimes you don’t know how it is going to taste and sometimes it doesn’t taste so well. You can add more ingredients or dump it all out and start over.”

Hatfield says that freedom comes when he explores new ideas outside of the mainstream. When designing a signature basketball shoe, for example, there’s a lot of units at stake and a lot of stakeholders involved. But when creating a new running spike, of which only five or six pairs may be produced, or a new boxing boot, that’s where there are aren’t people over your shoulder.

“It opens up and frees up your innovative mind,” he says. “I am looking to do something different because this one specific sport needs it. What we learn from that, we can then apply it to the masses.”

And that takes us back to Esparza. What started as a prototype for one boxer has turned into the HyperJab, a new way of creating a boxing boot in a world void of much option. Hatfield says he expects that we’ll see the boot on the feet of quite a few of the USA Boxing athletes by the time Rio rolls around.

As for Esparza, she couldn’t be happier. She’s been rewarded for meeting with Hatfield and letting him take her thoughts into the Innovation Kitchen. “He was going to be the genius he is,” she says.

Tim Newcomb covers stadiums, sneakers and training for Sports Illustrated. Follow him on Twitter at @tdnewcomb.