Exclusion to Exclusivity: The History of Women Running the New York City Marathon

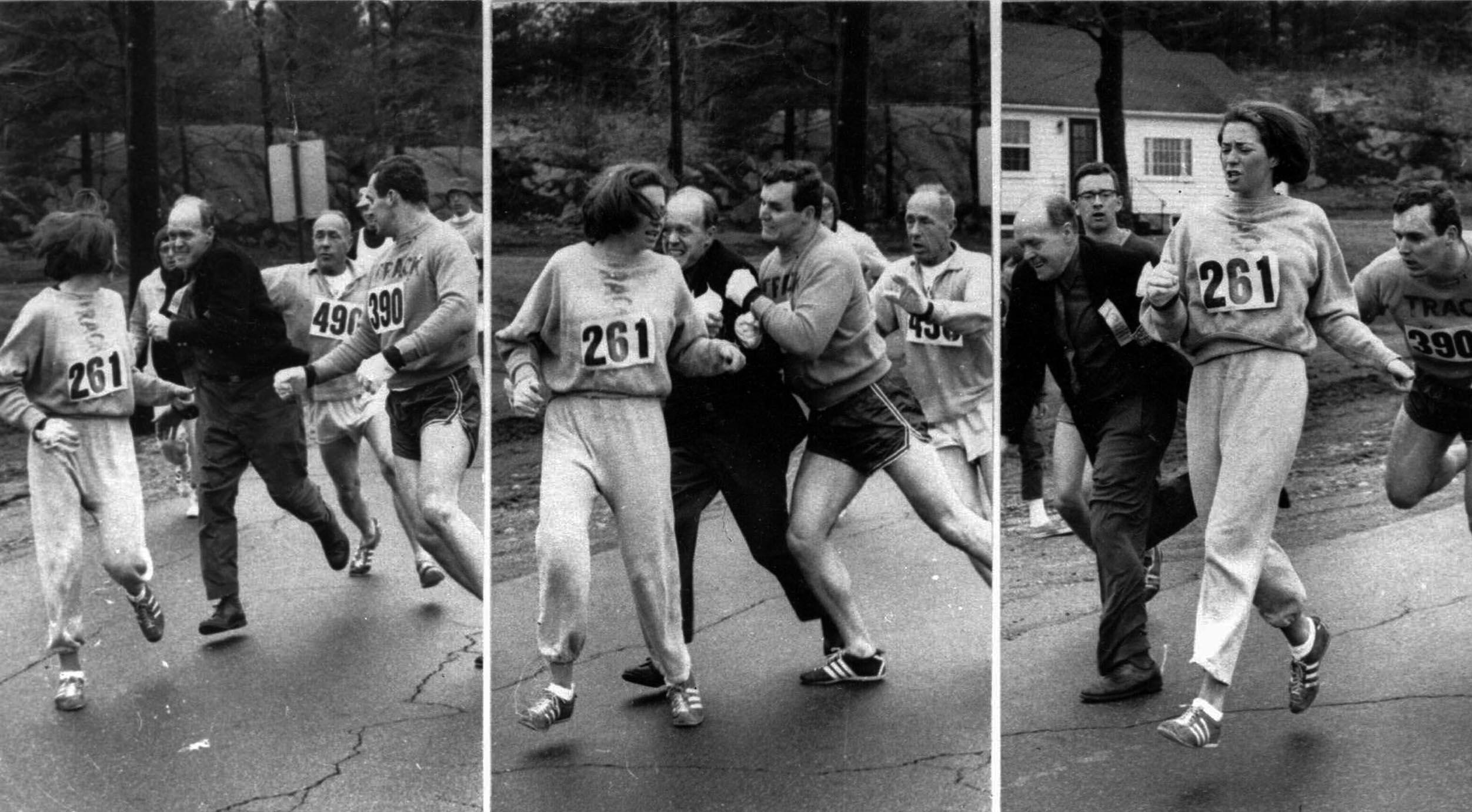

Kathrine Switzer is perhaps best known for her barrier-breaking run in 1967, when she became the first woman to officially finish the Boston Marathon, despite an official’s attempt to push her out of the 26.2-mile race.

But Switzer says that some of her most joyful runs—and her greatest victory—have come in New York. A longtime New York resident who has logged thousands of miles on the city’s streets, Switzer won the New York City Marathon in 1974 and is still the last New York resident to win the city’s signature race.

In 2017, 50 years after she made history in Boston, Switzer, then 70, lined up alongside more than 50,000 other runners—almost half of whom owed their place in the sport to her. It was Switzer’s first chance to run the five-borough course. When Switzer ran the race four times in the 1970s, it consisted of four laps around Central Park.

“The major marathons, like New York, have changed the face of our cities,” Switzer says. “Running is the most inclusive, diverse, egalitarian activity in the world.”

Just days before the 2017 marathon, a driver plowed a pickup truck down a crowded bike path along the Hudson River in Manhattan, killing eight people and injuring 11 others. The attack was the deadliest in New York City since Sept. 11, 2001.

“For a moment they thought they needed to cancel the race,” Switzer says. “I had people call me and beg me not to run because they thought I would be in danger. I said, ‘Are you kidding me?’ I am going to be running with 55,000 people. The guy on my left might be a different race from me. The person on my right might not speak my language. The person behind me might be of a different religion. But we don’t care about any of those things. We’re going to be plugging along for 26.2 miles together, encouraging each other, motivating each other, and then hugging each other, all stinky and sweaty, at the end of the race. What better example is there of inclusion, diversity, equality, and respect?

“I always say, ‘If we can do this in the New York City Marathon, why can’t we do it in the whole world?’ ”

The New York City Marathon, which began in 1970 and grew from a local road race in Central Park to the world's largest marathon, will celebrate its 50th running Sunday. The 2021 race will feature a particularly deep field of professional women runners, including Olympic bronze medalist Molly Seidel and Shalane Flanagan, who became the first American woman to win the NYC Marathon in 40 years when she crossed the finish line first in that 2017 race.

The race has come a long way from its humble and relatively homogenous beginnings. The first New York City Marathon, organized by New York Road Runners, took place on Sept. 13, 1970. The 127 registered runners each paid an entry fee of $1. Only 55 of them finished the race.

Nina Kuscsik was the only woman among the 127 entrants. She dropped out at mile 15 with gastrointestinal issues, but that wasn’t the end of Kuscsik’s story; she would return in 1971 and finish a close second to Beth Bonner. Both women broke the three-hour mark. (Bonner finished in 2:55:22 and Kuscsik in 2:56:04).

Kuscsik, like Switzer, had been strongly discouraged from running because doctors believed it was bad for their health. “People would tell us, ‘Oh, you shouldn’t run. You really can impair your ability to conceive and your uterus might fall out,’ ” she recalls.

Rules set by the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU)—the organization that governed all amateur competitive sports in the U.S., including marathons—forbid women from competing in any race longer than 1.5 miles.

Frustrated, Kuscsik and Switzer decided to join forces in the early ‘70s.

“We each used our skill sets,” Switzer says. “Nina did a lot of the hard, legislative work and sat through endless administrative meetings. She became an expert on rules changes. My specialty was organizing events, because I figured that the numbers and the enthusiasm would also speak for themselves. I think we were a great one-two punch.”

Kuscsik joined the AAU and became deeply involved in her local chapter. At the organization’s annual convention in 1991, Kuscsik made a breakthrough. Thanks to their exhaustive efforts, the AAU finally agreed to change the rules in 1971. But there was a hitch: The AAU would allow women to run in the 1972 New York Marathon, but not in the same race as the men. The women would have to start 10 minutes earlier.

“We were happy that the door had opened, a little bit,” Switzer says. “It was a start. Because when you get the door open, you can keep pushing it.”

That year, six women—including Kuscik, then a 33-year-old mother of three who earlier that year became the first woman to officially win the Boston Marathon—staged a protest. As the gun went off for the start of the race, the women sat down. They held up handmade signs, one of which read: “Hey, AAU. This is 1972. Wake up.”

When the gun went off for a second time to start the men’s race, the women stood and began running with them. Two women finished the marathon that day: Kuscsik and Pat Barrett, a 17-year-old high school cross country champion from New Jersey. Kuscsik was the official women’s winner, but the AAU added 10 minutes to her finish time. A photograph of the six women runners ran in the New York Times, and word of the protest spread.

“The sit-down in New York was both a publicity stunt and a statement for women’s equality,” says Switzer, who was working as a journalist at the Munich Olympic Games at the time of the race. “I think AAU looked silly because here we were, at the surge of the women’s feminist movement, where there were lots of sit-down strikes and demonstrations. We were trying to get attention for a cause.”

Soon after, the AAU scrapped its discriminatory rule. Kuscsik went on to win New York again in 1973, and to compete in more than 80 marathons in her lifetime.

Switzer won the New York City Marathon in 1974, an accomplishment she calls her biggest victory. She won the women’s race in 3:07—just short of her goal of a sub-three-hour mark—in 100-degree heat. Her 27:14 margin of victory remains the largest in the event’s history.

The 1974 race was historic on several other fronts. Switzer helped put the New York City Marathon on the map for both men and women by convincing race founder Fred Lebow to sign its inaugural sponsor, Olympic Airlines. The race used electronic timing equipment and runners were interviewed on local television, both firsts for the event.

Switzer has been there for nearly every significant step in the evolution of women’s marathon running since. She would run dozens more marathons and cover countless more as a journalist and TV commentator, all while traveling the world to advocate for women runners. Switzer also launched the Avon Running circuit, a series of 400 women's races across the globe that included the Avon International Marathon in London, in 1978. Because of the success of that race, which drew women from 27 countries and five continents, the International Olympic Committee voted in 1981 to add a women’s marathon to the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games. When U.S. runner Joan Benoit won gold, Switzer was in the broadcast booth, doing commentary for ABC.

Deena Kastor, then 11, listened to Switzer call Benoit’s win. Kastor was inspired to start running, and went on to become the U.S. record holder in the marathon and a three-time Olympian who won a bronze medal in the event at the 2004 Athens Games.

“There’s not a race weekend that goes by that I don’t pay tribute in my mind to Kathrine Switzer and Joan Benoit Samuelson and Mikki Gorman and Bobbi Gibb,” Kastor says. “They fought some pretty hard battles to smooth the way for the rest of us. The fact that we can not only compete, but compete with equal pay and still have our shoe sponsors support us through pregnancies and motherhood—those are really big, important steps in sport. I feel grateful and thank those women personally because of what they fought for.”

The 50th running of the New York City Marathon will be a major milestone in the city’s recovery from the coronavirus pandemic. Kastor says the celebratory mood leading into this year’s marathon reminds her of the atmosphere around the 2001 race, which was two months after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks on the city. Like this year’s field—which includes about 40% fewer runners than the 2019 event—the race field in 2001 was smaller. But New Yorkers turned out in full force to cheer on the runners as the city returned to some semblance of normalcy.

“It was right after 9/11, when we questioned whether the race should go on at all,” Kastor says. “It was such an emotional weekend in the city, just to see New Yorkers out on the streets. ‘United We Run’ was the slogan everywhere. New Yorkers really came together to uplift and inspire one another.”

Kastor finished as the top U.S. woman in her marathon debut at the 2001 New York City Marathon in record time for a U.S. runner’s debut, and had three top-10 finishes at the event throughout her career.

“I fell in love with the marathon distance when I debuted at the New York City Marathon,” says Kastor, who will cover this year’s race as a broadcaster for ABC and ESPN2. “It’s remarkable that a footrace that started as loops around Central Park is now one of the biggest events to happen in America’s biggest city. The New York City Marathon is still extraordinary. It’s big and it’s important.”

On Nov. 25, 1990, Liz McColgan became a mother. Less than a year later, she became a marathon winner.

McColgan resumed a full training schedule 11 days after giving birth to her daughter, Eilish, in Dundee, Scotland. Nine months after that she won a gold medal in the 10,000 meters at the World Championships in Tokyo. The following fall, McColgan raced to victory at the 1991 New York City Marathon in 2:27:24.

This week, McColgan—who also won the 1992 Tokyo Marathon and the 1996 London Marathon—will be inducted into the New York Road Runners (NYRR) Hall of Fame as part of the class of 2021. The sport has become a family affair for the McColgans. Eilish, now 30, is making her own mark in distance running. In August, Eilish reached the Olympic 10,000-meter final in Tokyo and three weeks ago, she smashed Paula Radcliffe’s 10-mile record. Now Eilish has her sights set on another goal: the same race her mother dominated three decades ago.

“She’s moving up to the marathon,” Liz says of Eilish. “I hope that one day she’ll run New York. That would be a really wonderful thing for me, because New York is my favorite place—and the New York Marathon is a special race.”

By 1991, the women’s field had grown to 5,200 runners, and the professional women’s ranks had blossomed. But McColgan and her fellow elite runners still faced obstacles—sometimes literal ones.

“Me and Lisa [Ondieki] were in the lead, running over the [Queensboro] Bridge,” McColgan says. “There was this guy carrying a sign. He kept trying to cut in front of us, because he knew the TV cameras in the moto were focused on us. He wanted to show off his sign. I remember the two of us getting quite angry at this guy. I was tempted to give him a big shove.”

Instead, she sprinted past him, pulled away with three miles to go and went on to finish more than three minutes faster than any other woman had run a marathon debut at the time.

“New York was a big, massive awakening for me, as far as where my career was going,” McColgan says. “I loved the American road racing scene. It was amazing to run the streets of New York, and have people cheering you on. There’s nothing else like it.”

This year, Kastor will cover the professional athlete races from the women’s motorcar. She says the race features one of its deepest fields ever.

“It’s hard to know who might come out on top,” Kastor says. “Like everyone, I’m excited to watch Molly Seidel. She’s such a strategic, tactical runner that it will be fun to see how she handles the New York City course and the stiff competition she’s up against. Kellyn Taylor and Stephanie Bruce are both moms who inspire so many people by being good at everything they do, from mom-ing to racing. There are so many good stories and strong competitors this year.”

In just her third marathon, Seidel won bronze at the Tokyo Games, finishing in 2:27:46 and becoming only the third U.S. woman in history (behind Kastor and Joan Benoit, in 1984) to medal in the Olympic marathon. Seidel said she borrowed a page from Kastor’s Olympic training log by running in heavy cotton T-shirts or sweatshirts to prepare for the heat in Japan.

The New York field features 12 women runners with personal bests under 2:28, including Olympic gold medalist Peres Jepchirchir of Kenya and Olympic silver medalist Abdi Nageeye of the Netherlands.

The elites will have plenty of company among the rank-and-file runners. Women’s road racing has grown significantly since the AAU’s rule change back in 1972. By 1980, 10% of marathon runners in the U.S. were women. Between 2008 and ‘18, women's marathon participation increased by 56.83%, according to RunRepeat. The 2019 New York City Marathon featured 22,746 female finishers—the most ever. Because of COVID precautions, this year’s field was capped at 33,000, but a similar percentage will be women runners.

Among them: Caryn Kelly of Edina, Minn., is running on behalf of Switzer's 261 Fearless Foundation. The nonprofit organization, which is a nod to the original bib number that Switzer wore in Boston, uses running as a vehicle to empower and unite women through local running clubs and events. In 2014, Switzer started getting emails and letters from women all over the world.

“They sent me photos of themselves running with the number 261 on their back—and sometimes tattooed on their arms,” Switzer says. “It had become this kind of cult number, meaning ‘fearless in the face of adversity.’ ”

Kelly will be running for charity, and wearing 261 on her back, but she is also running for herself. New York will be her 10th career marathon.

"I finished my first marathon at the age of 40," says Kelly, now 47. "I cannot thank Kathrine enough for the opportunity to help women around the world experience the sense of accomplishment I’ve felt through running.”

Switzer and her husband, fellow runner and writer Roger Robinson, now split their time between New York and New Zealand, and won’t be at this year’s race because of travel restrictions. She hopes to return for—and run in—next year’s New York City Marathon.

As she watches the race, Switzer will take pride in the fact that things have come full circle for women runners since the days when a separate start signified their second-class status. On Sunday, Seidel and the other elite women in the 2021 New York City Marathon will take off 30 minutes ahead of the men so that their race can get maximum visibility during the telecast, a change that Switzer lobbied for when she was a broadcaster.

“We have moved from exclusion to exclusivity,” Switzer said. “Women runners have earned the right to be front and center.”

Aimee Crawford is a contributor for GoodSport, a media company dedicated to raising the visibility of women and girls in sports.