Basketball With 12-Foot Rims? It Was Closer To Happening Than You May Think

On this day in 1954, the Hawks and Lakers played a game with 12-foot rims instead of the standard 10-footers.

Why? Because there was a mounting concern that it was too easy to score -- “Something has to be done to make a basket worth a cheer,” wrote one sports columnist -- and many feared the dominance of the big man was undermining the game.

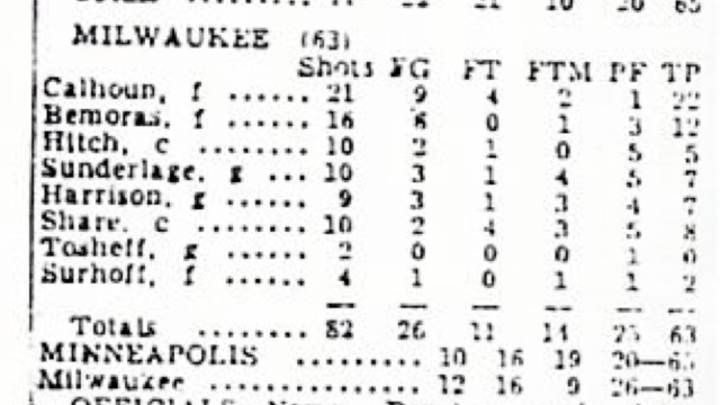

There was no bigger man in those days than Lakers' post man George Mikan, who'd led the Minneapolis club to four league championships in five years. A quick glance at the box score from the game suggests mission accomplished: Mikan scored 12 points on 2-for-14 shooting -- more than six below his season average.

basketball-reference.com

Most reactions to the rule change were negative.

“It threw the whole game out of sync and made it tougher on the smaller man," Mikan said. “It just makes the big man bigger."

Said Minneapolis coach John Kundla: “Nobody could hit the darn thing. The guys who usually couldn’t shoot were the ones who hit the most. And the big guys still got the rebound.”

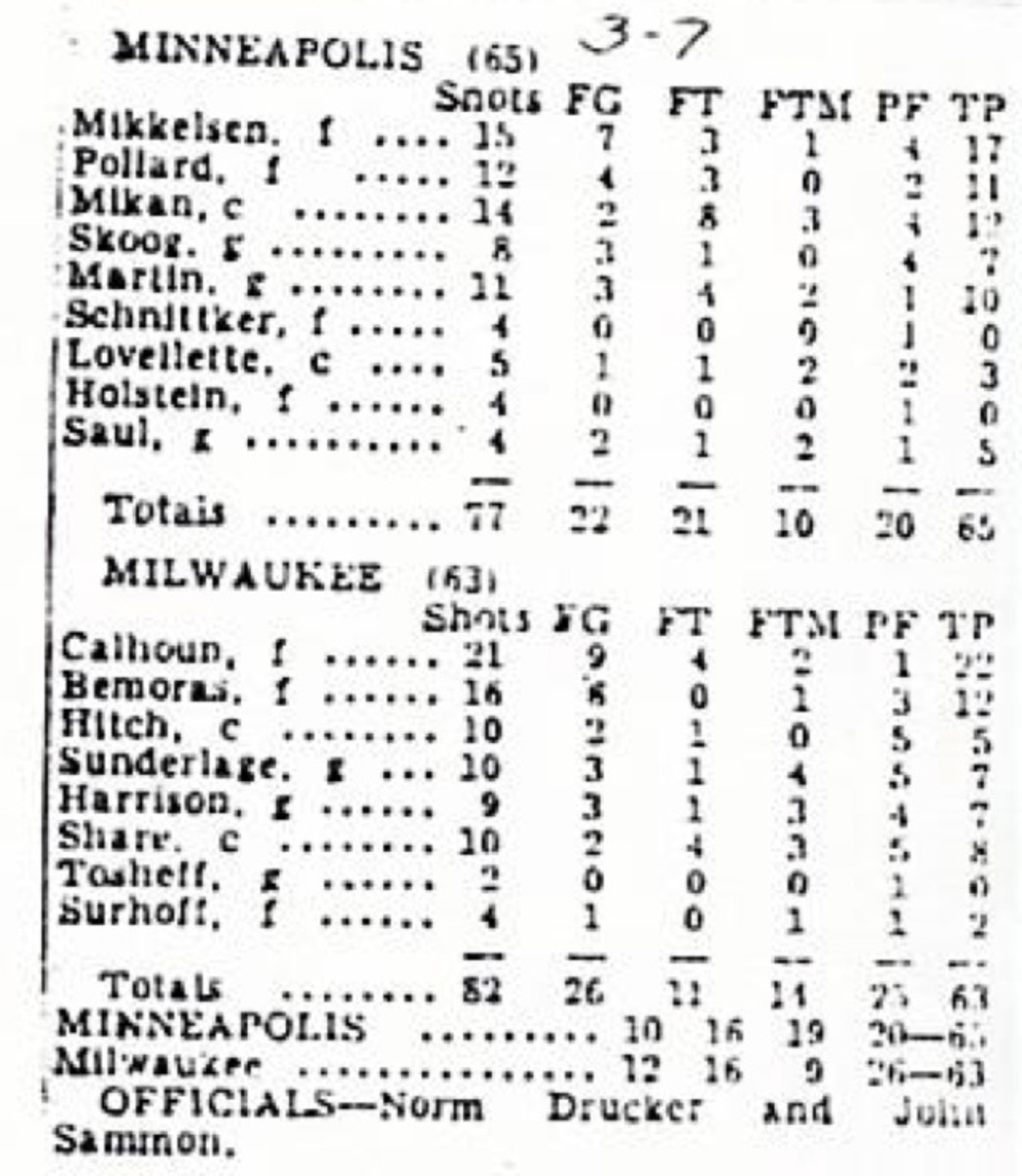

It wasn't the last time a higher rim was suggested. Thirteen years later, Sports Illustrated persuaded Tennessee coach Ray Mears to play his Orange-White preseason scrimmage with 12-foot baskets for the cover story of the Dec. 4, 1967 issue.

Richard Jeffery/SI

Mears divided his squad into two teams, splitting up his first stringers with 7' Tom Boerwinkle on the Orange team and 6'10" sophomore Bobby Croft on the White. The players practiced on the higher baskets for only about 40 minutes the afternoon of the game and again in the pregame warmup. In the contest, played before 5,100 curious people in Tennessee's Stokely Athletics Center, the Oranges missed their first eight shots, the Whites their first nine, and the overall shooting was poor—20% for the Oranges, 25.7% for the Whites, who won 43-36. Poor shooting was not surprising because none of the players had had enough time to become familiar with the new dimensions, but all agreed that they could achieve former accuracy with practice.

What surprised many was that the biggest man, Boerwinkle, who is fairly agile and quick, had the most difficulty. While he had 15 rebounds, a little above his average, he had trouble getting them, although most of the missed shots fell within a 12-foot radius of the basket. He had no chance at all to get the shots that hit the front of the rim. The rebounds usually caromed over his head and were taken by one of the smaller men. On many shots the ball took longer to come down, giving the other players time to crowd into the lane and fight Boerwinkle for the ball. Several times he had the ball stolen away when he came down with it. He failed to block a single shot and did not score on a tip-in. He made only one basket in 16 tries, a jump shot from the foul line.

The small men quickly learned they could shoot better from outside, and they concentrated on shots in the 15-to-25-foot range. Their accuracy, understandably, was not good, but it was apparent that the higher basket would encourage more long jump and set shots. There were fewer layups than normally, but the little men were more adept at this because they were used to shooting the ball up rather than literally laying it in, as big men often do on 10-foot baskets. Boerwinkle's layups almost always hit the back of the rim.

Since then, higher rims have seldom been seriously considered.

Unless you count MTV's Rock N' Jock B-Ball Jam.