Miyamoto, The Creator: Sitting Down With Nintendo's Visionary Game Designer

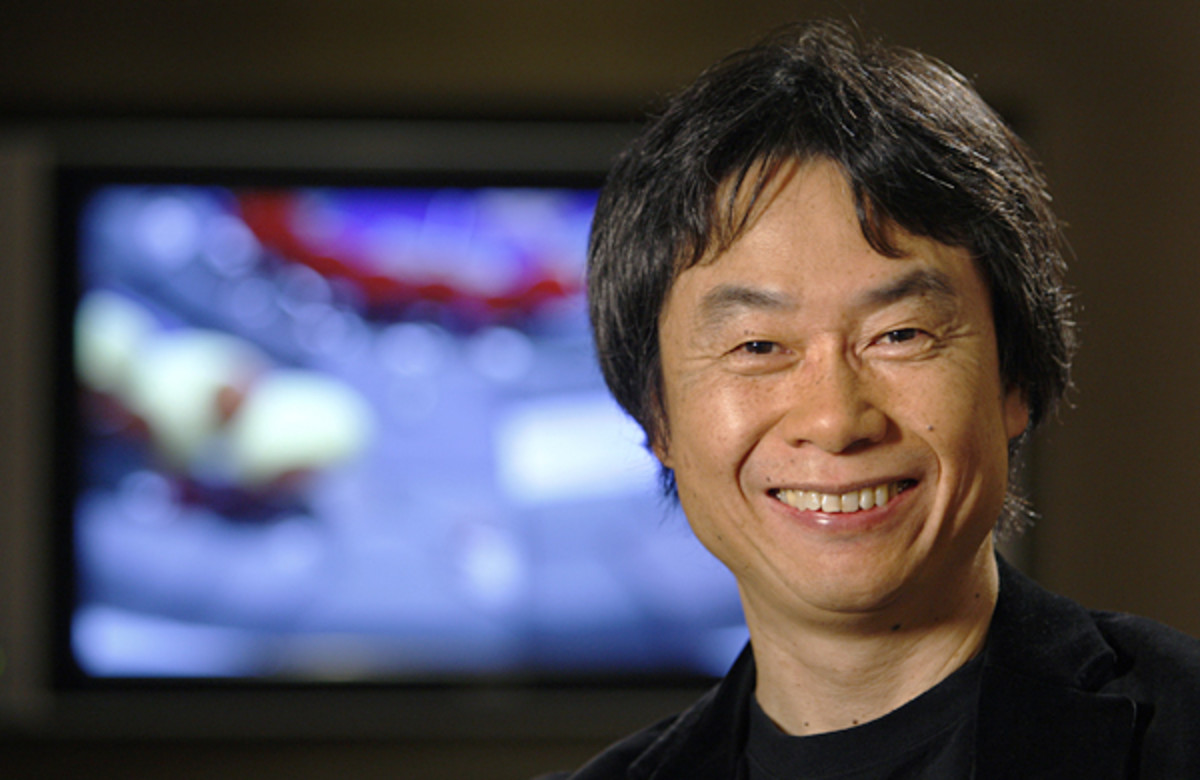

AP

It's been 30 years since Nintendo designer Shigeru Miyamoto introduced Mario Bros. to the world and essentially invented the modern video game industry. I sat down with the 60-year-old creator of such iconic franchises as Mario, Donkey Kong and Zelda last week in New York to talk about finding creative inspiration in daily life, how to stay current in an ever-changing industry, the importance of tradition at Nintendo and maintaining the "Mario-ness" of Mario.

Why has Nintendo named 2013 the "Year of Luigi"?

Shigeru Miyamoto: There were two reasons. First, we have a number of different games starring Luigi coming out this year. But this also happens to be the 30th year since Luigi first appeared in his very first game, which was the original Mario Bros.

What about the new Luigi's Mansion game are you looking forward to sharing with the players?

Miyamoto: We made the original Luigi’s Mansion (in 2001) for the Nintendo GameCube. At the time we were developing it, we really wanted to have 3D visuals for it, even back then. We actually worked on a 3D screen that we connected to the GameCube and experimented with a 3D version of that game. So when we launched the Nintendo 3DS, we thought it was natural that we would finally bring Luigi into 3D.

What’s fun is that it’s almost like you have a dollhouse in front of you and Luigi is inside it exploring and chasing the ghosts. And the play control is sort of the traditional Nintendo-style play control: it uses a lot of the interface options of the Nintendo 3DS, but rather than force you to learn all these complicated controls at once, it teaches them to you intuitively one by one. so you gradually improve over the course of the game. You then use all of these abilities to solve puzzles and try to capture the ghosts, so it’s very satisfying to learn and master the controls.

How can you tell if a game will be interesting? How do you know if you're making it too difficult or too easy for the player?

Miyamoto: It is a challenge. We’ve tried to design this not in a way that it just gets more and more difficult as the game progresses. Instead, it's more that what you can do expands as the game progresses, because you do have a big gap in skill level between people who are very good at action games versus people who aren’t as good at action games. We’ve tried to strike a balance that’s somewhere in the middle. By giving them more things to do, it can appease both audiences.

Can you talk about your Pikmin, the newest of your franchises? I understand the character was inspired by your time spent gardening, one of your favorite hobbies.

Miyamoto: When we were creating Pikmin originally, we started by wanting to create a game where you had a big group of these creatures that were all moving around and doing things together and you were giving them orders. The more we developed the game, the more ant-like the Pikmin characters became, that sort of reminded me of my work in the garden. So it's a less of, "I was gardening and I came up with the idea of Pikmin characters," and instead more of as we made Pikmin it reminded me of my gardening hobby.

Have you connected with real-life experiences similarly while developing previous games?

Miyamoto: As I've gotten older there have been more and more examples of that style of development. For example, Nintendogs: what really got that project started is I had started raising a dog and taken it to training classes. Taking the dog to training and meeting the other people who were training their dogs kind of led me to this idea of, "Oh, maybe I could make a game out of this."

Wii Fit was another example. It really started with me weighing myself every day. There's actually a diet where you weigh yourself daily and you track your weight on a graph, and I found that just tracking my weight on a graph was interesting. I thought I could take something like that and bring it into a video game and turn it into something new. So I am seeing more and more examples of this as I get older.

The industry has changed and the technology has advanced so much in the 30 years since Mario Bros. came out, but are there principles about making the games that have stayed the same?

Miyamoto: As media has changed over the years and the technology has changed games as well, what becomes important is still designing those games and maintaining basic principles. And to me what's one of the most important things is making sure that, as a developer, you are able to connect with that shared experience and that shared connection that you have to the player. In particular when you're designing a game, you need to be able to to think about trying to help the player play in creative ways. Create the game in ways that invite them to try to experiment within the gameplay and try different things. Make sure that as an interactive medium, when they try something in the game, that you have a response for what they're trying to further encourage their creative play. These are some of the basic rules that we still adhere to even as games have evolved and I still speak to my teams about trying to maintain.

Nintendo more than any other gaming company features characters that have recurred and been a part of people's lives for 30 years now. Can you talk about the importance of tradition at Nintendo?

Miyamoto: There are two things that we really focus on. The first is maintaining the "Mario-ness" of Mario. We talk a lot of about what it's OK for Mario to do or what Mario should be -- and what Mario shouldn't be or shouldn't do. In terms of what he should do, we've always viewed Mario as being a character that should always be doing something new. And then in terms of what Mario shouldn't be doing, we really want Mario to be a character that people can trust. We want parents to feel that they can trust the character and they can sit down to play Mario games with their kids. We would never use Mario in some type of gambling product. We don't have Mario engaging in a lot of violence or things like that. We want him to be a friendly character that is welcoming for people.

The other challenge that we often have is that, as time passes and we have younger and younger developers joining Nintendo, they now are at a point where they're joining the company and they have in their mind their own sort of fixed image of what Mario should be based on their experiences with Mario. And oftentimes they think that Mario should be more child-like because of their childhood memories with him. So when they join the company, they have a tendency to want to try to bring Mario closer to their image of what Mario is or what he should be. Instead what we have to do is educate them and help them understand this is the sphere that Mario exists in and this is what Mario is, to try to help them understand how they should handle the character when developing games.

I noted that Mario should always be doing something new, but the other thing that's important is that the player should be able to feel as if Mario is a part of them, so they can feel it when Mario is running or when Mario is lifting something or when Mario is attacking something. It feels like it's sort of a miniature version of them that's doing it.

Do you think games can be more than just fun?

Miyamoto: It depends on the scope and direction of how we talk about it. But if you think about video games as an interactive medium, the people who have been a part of the games industry and are developing video games and have been for a long time really have a very high level of skill in terms of developing interactive interfaces. Nowadays of course computers have become much more interactive, but we're even seeing things like washing machines that have interactive features. And so if you think about the fact that video game developers have this tremendous interactive technology at their fingertips and this tremendous know-how of how to apply that, then certainly you could look at how the interfaces that they've designed and developed over many years in video games could potentially be something applicable in a very broad range of different devices and different uses. I guess in that sense that's one example of how the thinking or the development that goes into video games could certainly expand beyond the scope of simply creating something that's fun.

Similarly we also see how gradually with some things like smartphones, you're starting to see these devices that are playing entertainment but have many other functions as well. I start to look at even something like Wii U as being a system that really is much more. It's almost that it's not simply a gaming device, but it's a device for the living room that brings benefits to practical life and practical use to the living room, to the TV, and allows people to enjoy these benefits through interactive means. So those are a couple of different ways how I see the technology of video games moving beyond simple entertainment.

Jonathan Alcorn/Getty Images

How much has the process and workflow of developing a game changed since the 8-bit days?

Miyamoto: Of course one of the biggest new challenges that we face in development is that the teams have gotten so much bigger and you have to manage all of that. And particularly where you run into challenges is oftentimes once you've made a decision about a direction you want to take with a game, it can take a long time to get the team moving and get them to produce a result that then reflects the decisions that have been made. So what becomes particularly important is that, although the way and the scope of game development has changed, is still adhering to some of those core aspects that remain from the early days, like being able to have the team function in a way that you're able to get to the core elements of a game. You must be able to quickly implement changes and decisions on a small scale to see the results and be able to operate from there before requiring the full scope of the team to try to produce that. In particular what we do is we still try to maintain a similar style of how we developed games in the past, which is we will focus on creating that core structure of play with a small team very early on before bringing in a large number of people to finish the game off.

What is the hardest part of your job?

Miyamoto: [After thinking for a half-minute, as assistant jokes, "This," and he laughs.] Probably it's the fact that we're operating so many projects simultaneously. Taking each one individually, they're all a lot of fun, but when you have so many going on at one time, that's when it starts to get hard.

Your assistant makes a good point about talking with the press. You rarely give interviews. It's not unusual for artists to not want to talk about their work because it can demystify it in a way. There are many filmmakers that don't like talking about their movies. Is it something where if you had a choice you would rather not put it into words. I won't be insulted!

Miyamoto: Right. I don't think it's the type of thing that I should be explaining to people.

What are some of your other favorite pastimes outside of video games?

Miyamoto: I do really like going to live shows and performances. I really enjoy Cirque du Soleil.

Is there a genre you would like to explore someday that you haven't already?

Miyamoto: Not really, but I have been dabbling in creating some Pikmin short videos. I'm working with an outside animation studio and kind of quietly doing this on my own, but that's something I've been exploring.

Certainly as a company we are always creating something that's interactive, but with my background having created manga comics and things as a kid, I wanted to dabble a little more in a more passive medium. It's not related particularly to any games or anything, but I just wanted to see what it was like to make some animations with the Pikmin running around. Would you like to take a look? [He shows me a two-minute animated short on his Nintendo 3DS XL.] This is just a short movie. I want to give people the feeling that there are perhaps many, many Pikmin all around the world, right in their vicinity.

We also were looking for other opportunities to get the Pikmin in front of people, and we had a movie theater company that said they wanted us to create a "Put on your 3D glasses" promo video using the Pikmin. [He shows another light-hearted 30-second short.] This is something that's running in theaters in Japan right now. So I've been having fun with this sort of thing lately.

When a new technology breaks -- whether it's online play or 3D gaming -- is it exciting for you to have a fresh palette for your ideas?

Miyamoto: We dont have anything concrete to share lately, but a couple of recent examples would be Miiverse, which takes advantage of the network functionality to allow players to communicate directly with one another. Or the Mario vs. Donkey Kong series of games that we've released, which have had level editors in them that allow the gamers themselves to create their own levels and share those amongst each other. So I think that certainly now, as network connections have increased for people and they have more access to networks, that's going to open up new opportunities for us to then change the way that they play with one another.

And in Japan we've released a game called Animal Crossing: New Leaf, which is going to be coming to North America this year, which has been a big hit and performing very well. One of the groups of people that's actively playing the game is adult females and what's interesting is that the gameplay doesn't end with the game itself. We're seeing people using Twitter to communicate elements of the game to others and share their experience. We're also seeing people take advantage of the 3DS StreetPass functionality to exchange game data or send gifts to people that they don't know or money to people to help them in their game. So we're seeing a lot of different ways in which the gaming experience is expanding beyond just the individual experience that you have on your own.

Wii Sports was a major hit. You've also got a new Mario Golf game coming out this year. You're better known for creating the Donkey Kong, Mario and Zelda games, but can you talk about your role in developing Nintendo's sports games?

Miyamoto: Originally when we released the NES, one of the primary reasons we added a second controller to that system was because we wanted to be able to make sports games, because we felt that if we're making a baseball game, we want to be able to have two people play against each other. And back then we created a lot of different sports games in Japan, like Ice Hockey or Volleyball and many others.

Then we took a break from making sports games for a while, and partly that was because we developed the early sports games and then we started to see the third-party publishers were starting to adopt the sports games and kind of develop those further. So we sort of let them move forward with the sports games while we decided to focus on other areas and creative efforts. But then over time what happened is we decided to take another look at sports. But rather than just creating a new version of a traditional sports game, we decided to bring Mario into it and make a very Nintendo-esque sports game using the Mario characters. So that's sort of been our history with the sports games over the years.

I discussed interfaces with you earlier. To me one of the most important things about sports games is making sure that you're giving the player the sense that they're performing that sport themselves or those activities themselves, and then also trying to give them a feeling as if they're performing as sort of a professional level.

Very early on when we approached a sports game -- taking golf as an example -- before that, the golf games that you might see on a PC or something would focus specifically on the numerical score. You might see a score in the 70s or the 80s or something. What we did is we took an approach where we instead looked at it in terms of how far above or how far under par you were, rather than just looking at the numerical score.

The other thing that we did on the NES was when you would start off on the tee and you would hit the ball and you would follow the trajectory of the ball through the air and see it land on the green, it was as if you were watching a golf tournament on television, so that you had a lot of production elements that you might see when watching a sport, coupled with the fact that you were doing the sport.

And then as we started to see other companies make more and more sports games, the direction that many of them went in was that they might tie up with a professional athlete, a sports star, as sort of the face of the game. They started to devote a tremendous amount of resources to creating game versions of actual stadiums and things like that. We started to see what I kind of called the "datafication" of sports games.

So when we created Wii, what we decided to do was that we wanted to bring sports games sort of back to that original starting point, and really just focus only on the elements of the sports game that's going to allow the player to feel like they are actually playing that sport themselves.

Well, Nintendo might have been the first to bring in a real-life athlete, if I'm not mistaken, with Mike Tyson's Punch-Out!! And that game featured Mario too.

Miyamoto: [Laughs.] That's correct. He was the referee.

What would you be doing if you had never gotten into making video games?

Miyamoto: I would probably be designing toys or something like that.

What would you consider your proudest achievement in all your time in the industry?

Miyamoto: It's not necessarily a specific moment, but it's very flattering to hear the cheers and applause of fans who have played the games. So not any specific event, but the opportunities that I've had to be on stage in front of an audience and hear that reaction have all been very fulfilling.

Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty Images