Ten Athletes Who Are Deserving of Hollywood Biopics

Prior to this year, if you had asked any sports fan to name the athletes most deserving of a Hollywood biopic, there’s a good chance Jackie Robinson would have ranked near the top of most lists. In many ways his story is, at least in theory, the perfect sports movie: It has an underdog who ultimately prevails. Its context is one of cultural revolution. And its antagonist is one of the most compelling in the sports-movie history—namely, societal norms, as evinced by the behavior of much of the American public. There was no way a movie about Robinson wasn’t one day going to be made. And now we have it. 42. Opening today.

There aren’t many, if any, other sports stories of the magnitude of Robinson’s—but really, for Hollywood’s purposes, there doesn’t need to be. David O. Russell’s 2010 film The Fighter earned six Oscar nominations, two of which yielded golden statues, by telling the story of a boxer, Micky Ward, who was largely unknown to the general public. (For that matter, how many people could name him even after having seen the movie?) A good story is a good story—and as ten of our writers argue here, plenty of great ones remain untold.

Walter Iooss Jr./SI

Bill Walton

Walton obliterates the old Fitzgerald adage: His is an American story with more acts than King Lear. There were the NBA years, first with Portland where as the number one overall pick he was considered the franchise savior—in 1976–77 he led the Trail Blazers past Kareem and the Lakers, and then Dr. J and Philadelphia, for an NBA title. Then came the lost NBA years, injury after injury and tons of missed games, before winning both Sixth Man of the Year and another title with the Celtics in 1985-86. A lifelong stutterer, he improbably became a broadcaster for 19 years, and fought through crippling back pain (and the suicidal thoughts it triggered).

But that’s all epilogue. Those who saw him play before the knee injuries, during the UCLA years when everything was still in front of him, swear he was the greatest college basketball player ever created. A 6-11 center with a point guard’s feel for the game, Walton made 21 of 22 field goal attempts in the 1973 NCAA title game and won the Naismith Player of The Year award as a sophomore, junior and senior. But Walton’s interests went well beyond basketball: As a UCLA undergrad, he hung out with radicals, including Jack Scott, who famously hid Patty Hearst and other members of the Symbionese Liberation Army at a Pennsylvania farmhouse. He joined sit-ins to protest the war in Vietnam. Walton was an athlete/radical leading teams to titles. In an era of Nike and One Shining Moment, that seems almost inconceivable. —Richard Deitsch

AP

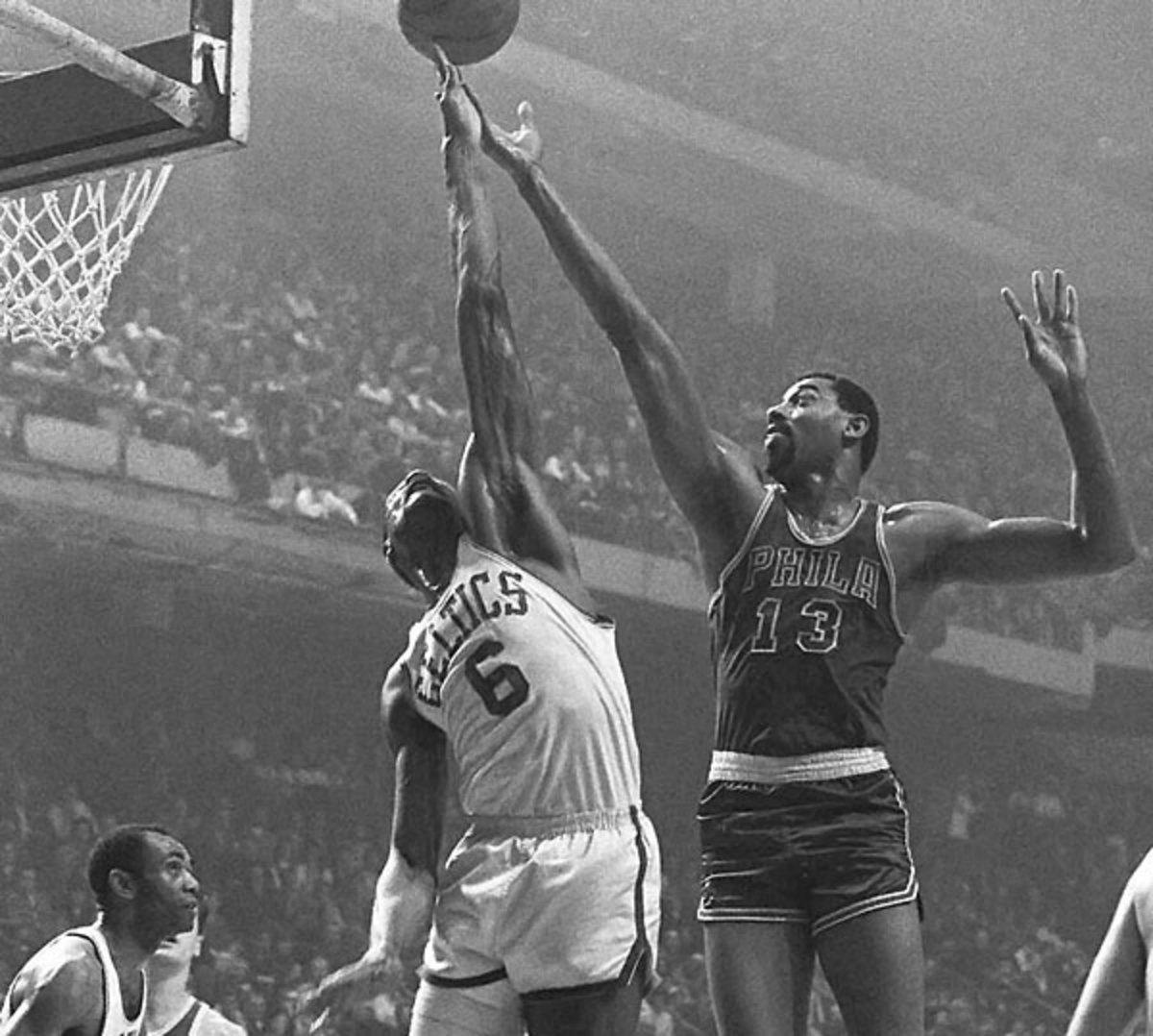

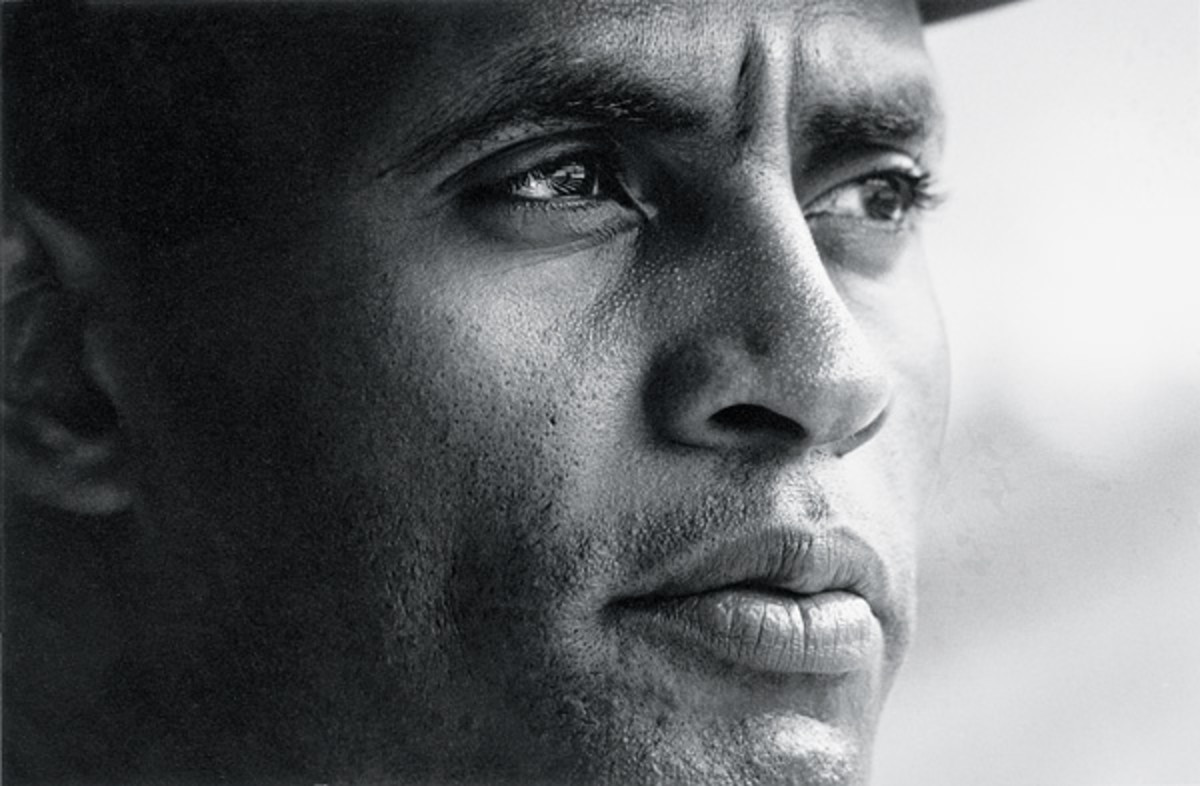

COMBOPIC: Wilt Chamberlain and Bill Russell

I anxiously await the day where we can fully unravel the relationship of Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain in cinematic form—those two giants of the early NBA who spent their careers circling each other. Russell as the consummate winner and model athlete, who had to deal with overt racism despite his good-guy charms. He played the game the "right way," by most any standard, which contrasts in compelling fashion with Chamberlain's focus on individual successes. The Stilt was a creature of excess, be it in bucket-getting or womanizing, which bore a stark contrast to the prudence of Russell's game and lifestyle. Seeing those two—a league apart, in terms of geography and sensibility—gearing up toward one of their legacy-defining matchups in the NBA Finals would make for magnificent theater. —Rob Mahoney

Harry Warnecke/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images

Alice Marble

Look up Alice Marble and you’ll find her listed under “tennis player.” Which is a bit like finding Joan of Arc under “shepherdess” or Chuck Barris under “game show host.”

Oh, make no mistake: Marble was a hell of a tennis player, one of the most accomplished ever. A girl growing up in the Bay Area, Marble showed a remarkable ability to smack a ball and became the unofficial mascot of the San Francisco Seals—“Little Queen of Swat,” no less than Joe DiMaggio nicknamed her. She soon switched from baseball to tennis, and despite enduring the trauma of being raped in Golden Gate Park as a 15-year-old, she becme a top junior and then a peerless pro. The first women to serve-and-volley (kids, ask your parents what that means), she won the U.S. Open in 1936, 1938-40 and Wimbledon in 1939. In both 1939 and 1940 she was the AP’s Athlete of the Year.

But then comes act two and the really good stuff: After retiring in the 40s, Marble went to work at DC Comics and edited the Wonder Woman series. Around that time, she married Joe Cowley, a soldier sent to fight in World War II. Marble miscarried their child when was pregnant at five months. Days later, she learned that her husband had been killed in action. She tried to commit suicide. She survived, however, and then—because the narrative could use a twist—decided to become a spy for U.S. Intelligence.

The details of the mission are vague. But they involved renewing contact with a former lover, a Swiss banker named and Nazi sympathizer Heinz Steinmetz, and obtaining Nazi financial data. The government suspected that Steinmetz had obtained valuable art on behalf of the Nazis. Having moved to Switzerland to reconnect with her old flame, Marble was tasked with photographing the artwork and sending back reports. As Wikipedia so nonchalantly informs: “The operation ended when a Nazi agent shot [Marble] in the back, but she was extracted and recovered.”

Me? I’m watching that movie. —Jon Wertheim

Neil Leifer/SI

Roberto Clemente

There were plenty of moments that made Clemente a memorable ballplayer—him hitting .331 and averaging 17 homers and 81 RBIs from 1961 to 1972, or the many plays he made with his unearthly arm, the one that once threw out Cincinnati’s Lee May, who foolishly tried to score from third—on a single to Roberto’s rightfield. But they aren’t what made him the mythical man worthy of the 40 schools and two hospitals that bear his name.

It was in the quiet moments, mostly unseen, that made him one of the most compelling sports figures of the 20th century. It was the way he’d make change from a $20 bill, then walk the streets of an impoverished Latin American town, passing out change to those who needed it most. Or the way in which he moved a mostly white, Texan audience to a standing ovation at a banquet in Houston in 1971, when he told them, ''If you have an opportunity to make things better, and you don't do that, you are wasting your time on this earth.'' All the while, he was challenging the public notions of what it meant to be a Latino—and a black Latino, at that—be it by yanking away the microphone from the sportscasters who Anglicized his name to “Bob” against his wishes, or speaking Spanish into the American television cameras after leading the Pittsburgh Pirates past the Baltimore Orioles in the 1971 World Series.

If Hollywood is all about it’s endings, few are more heroic than Clemente’s. On Dec. 31, 1972, Clemente boarded an airplane saddled with relief supplies he’d collected for the earthquake-ravaged Nicaragua. The plane was faulty, the pilot, flawed. We know what happens next. The camera cuts to the single sock floating—the only remnant of Clemente that would ever be recovered. The ending is sad, but it's not tragic, because it’s Clemente’s physical death that gave birth to his immortal legend—and the real tragedy of his story would be if we forgot to tell it. —Melissa Segura

AFP/Getty Images

Baron Gottfried von Cramm

Nazis. Homosexuality. Tennis. Rebellion. Throw it all together and you have one of the most overlooked sports stories of the 20th century: that of Baron Gottfried Alexander Maximillian Walter Kurt von Cramm. In the 1930s, only former heavyweight champion Max Schmeling rivaled Von Cramm as a German national hero. The two-time French Open champion was dashing, graceful, and by all accounts, everything you could imagine the most principled sportsman to be. He was also gay. Von Cramm was a private man but never concealed his homosexuality. The locker room knew, female suitors knew—and Hitler knew, too.

Von Cramm made no secret of his disdain for Hitler and the Nazi Party. His success on the tennis court kept the Nazis at bay, but they continued to keep a watchful eye on him, waiting for an opportunity to swoop in. That day would come in 1937, following a Davis Cup match between Von Cramm and the American Don Budge. Before they took the court, Von Cramm reportedly got a call from Hitler himself, who made it clear how much he wanted Germany to defeat the Americans. Von Cramm lost 6-8, 5-7, 6-4, 6-2, 8-6, and when he returned home he was greeted by two Gestapo agents and charged with "sex irregularities". Released after five months in prison, he was eventually drafted into the war, where he was dishonorably discharged. In the end it's just a great story of a German patriot who grew up in a more cosmopolitan and tolerant Germany, and refused to bow down Hitler. It doesn’t have a happy Hollywood ending, but hey, neither does Moneyball. —Courtney Nguyen

Sugar Ray Robinson

As subjective, disorganized and chaotic as boxing may be, no sport has a more clear-cut or definitive G.O.A.T. than Sugar Ray Robinson, born Walker Smith Jr., in 1921, the welterweight and middleweight champ who had a mind-boggling peak record of 128-1-2 and inspired the concept of "pound-for-pound" greatest. Yet his flamboyant lifestyle out of the ring, where he was one of the first black athletes to establish himself as a star beyond sports, made him a towering social figure of the '40s and '50s: an embodiment of black masculinity and cool. Sinatra hung at the nightclub he owned. He famously drove a pink Cadillac. He effectively invented the modern sports entourage, a term first thrust upon him by a steward during a visit to Paris. I'm talking swag. Yet nothing gold can stay: He retired broke in 1965 after burning through $4 million in lifetime earnings, struggled through failed careers in singing and acting, endured bouts with diabetes and Alzhiemer's before dying in poverty in 1989.

The scope of Robinson's life and times—from his coming of age in Harlem during the vibrant post-Renaissance years all the way through his fall from crossover prominence, eclipsed by political firebrands like Ali, amid the Black Power era of the mid-'60s—would lend itself perfectly to awards-season fare, ticking nearly every box on the Best Picture checklist. —Bryan Armen Graham

Mark Rucker/Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images

Bill Veeck

For all of their bucks and bluster, few team owners rise to the level of being worthy of on-screen depiction. Bill Veeck Jr. was the exception to the rule. As one of baseball's greatest mavericks, he left an indelible imprint on the game, brawling with the powers that be as he bounded from team to team across a span of more than 40 years. As the son of the president of the Chicago Cubs in the 1930s, he planted the ivy on the walls of Wrigley Field. As the owner of the Cleveland Indians, he integrated the American League with the signing of Larry Doby in 1947, just months after Jackie Robinson had broken the color barrier with the Dodgers. The next year, he added Satchel Paige as well, putting the finishing touches on a team that brought Cleveland its first world championship in 28 years (and its last one, too). As the owner of the St. Louis Browns, he was willing to do just about anything to draw fans to the down-and-out team, including signing 3-foot-7 Eddie Gaedel to pinch-hit, and using placards to poll the crowd—such as it was—about in-game strategies. As the owner of the White Sox during two separate stints, he brought an exploding scoreboard to Comiskey Park, oversaw the team's first pennant in 40 years in 1959, and brought a common touch as an executive by conducting his business in the full view of the public as he negotiated trades.

A movie covering Veeck's exploits in the game could be vastly entertaining, and at one point, it appeared as though one might come to the screen. In Neal Karlen's Slouching Towards Fargo, an entertaining account of the mid-Nineties indieball St. Paul Saints, co-owner Bill Murray was said to have acquired the screen rights to Veeck as in Wreck, the classic autobiography. He wanted to play the part as "a fan who made it all the way to the Hall of Fame". According to Karlen, the moneymen had given the green light, and Sigourney Weaver was in place as Veeck's wife Mary Frances, but a screenplay hadn't been approved. Nearly two decades later, the project remains unrealized, but in an era where faceless corporate owners have become the rule, it's needed more than ever. —Jay Jaffe

Bill Barilko

Look, not every hockey movie has to revolve around knuckle-chucking goons or Emilio Estevez working through his childhood traumas by coaching a lovable group of pee-wees. We've got bigger stories to tell, too. You've heard of Bill Barilko, right? The guy who scored in OT to clinch the 1951 Stanley Cup for the Maple Leafs? Okay, now picture this: The scene opens on a diver surfacing in the middle of a cold, dark lake in Northern Quebec. He waves frantically to the men on the support boat anchored not far away, then gives the signal. "He's found it," one of them says.

What the diver discovered that day in 1962 was the wreck of a small plane that had been lost for more than a decade. Inside were the remains of Barilko, the unlikely hero of what might have been greatest Cup Finals ever. You had Toronto and Montreal, the Forever Rivals, battling through five consecutive overtime games. In the deciding contest, there was Barilko, ignoring his coach's screams to stay back on defense, jumping up into the play instead and scoring the winner.

He became the toast of English Canada. I mean, they made a hockey card of it and everything. His career was on the rise—but he would never play hockey again. That offseason, he and a friend were on a fishing trip when the plane was lost. Though he was presumed dead, no one really knew. The mystery hung in the air for more than a decade. And it was as if his disappearance cursed the Leafs: They didn't win another Cup until the year he was found.

Barilko's story has already achieved mythological status in Canada, celebrated in the book Without A Traceby Kevin Shea, and in the song "50 Mission Cap" by The Tragically Hip, but it's aching to be told on film. There’s even a Tinseltown connection: before being promoted to the Maple Leafs, Barilko had a stint in the old Pacific Coast Hockey League. His team? The Hollywood Wolves. —Allan Muir

Peter Read Miller/SI

Herschel Walker

A chunky, stuttering 13-year-old Georgian boy of little means transforms himself into an elite athlete through a self-concocted daily regimen of 2,500 sit-ups, 1,500 push-ups, and a battery of excruciating exercises (cue the montage) to become one of the fastest high school runners in the state, a star running back at University of Georgia and a Dallas Cowboys standout. Walker does this all while battling dissociative identity disorder, once known as multiple personality disorder, a mental condition he’s silently and unknowingly suffered through since childhood. It explains the uncontrollable fits of anger and blackout periods he’s experienced, and though it causes irreparable harm to his marriage, the diagnosis and treatment finally allows him to soar to even greater heights: earning a spot on the U.S. two-man bobsled team at the Olympics, and then, in his late 40s, winning two Strikeforce MMA bouts. It’s a fascinating jigsaw-puzzle of a life. —Loretta Hunt

Hy Peskin/SI

Ted Williams

There’s a lot that’s appealing about The Splendid Splinter. Consider the resume: At the height of his career, after following the game’s last .400 season (in 1941) with a Triple Crown year, he enlisted as a US Marine pilot. He was awaiting orders to join the fighting in the Pacific when World War II ended. Having missed three seasons, he returned to the Red Sox and picked up where he left off—another Triple Crown, a couple of MVP awards and All-Star Game appearances in each of the next six seasons. Then he was called to serve in the Korean War, where he flew 39 combat missions and was awarded several medals and decorations. After missing two more seasons, it was back to baseball, where Williams continued to perform as an All-Star until his final trip to the plate—in which he hit a homer, of course.

And then there’s the added drama of the discord that existed between the greatest Red Sox player and both the fans and the media. Williams was fined on more than one occasion for obscene gestures at the ballpark, and he dubbed the baseball press “the knights of the keyboard.” One member of that royal family singlehandedly deprived Williams of being the 1947 MVP, leaving him off a 10-name ballot. After a Triple Crown season.

But the biggest selling point is the ultimate biopic cliffhanger ending: Today the body of the greatest hitter in baseball history remains cryogenically in a lab. For that reason alone, one would think that David Lynch is just waiting for the call. —Jeff Wagenheim