Tribeca Film Fest Wrap-Up: Highlighting a Bunch of Sports Movies You Can't Watch (Yet)

For the seventh year ESPN and the Tribeca Film Festival teamed up to remind the industry that some of the best movies are those that capture the daily operatics of sports. Among the films screened during the recently-concluded fest were Big Shot, the latest of ESPN's 30-for-30 series (now a misnomer for a franchise with installments numbering well into the 50s), as well as the first four of its new "Nine for IX" project: nine films by and about women to commemorate the 40th anniversary of Title IX. I went; I watched them all; I gave out awards. (This being sports and all.)

BEST INDUCER OF HEAD-DESK SPASMS: Big Shot

Director: Kevin Connolly

In 1996, when the Islanders were vetting prospective buyer John Spano, there were so many red flags it could have been a Christo installation. Just a couple phone calls would have outed him as a fraud whose biggest asset was his ability to falsify documents. So how did theTexas conman become an NHL owner? Says Spano in Big Shot, “It’s not as difficult as you might think.” Among the things that elicited incredulous groans from the audience:

- The rash of excuses the Islanders let fly, such as that one time Spano wired payments of $5 million and $17 million but because of some kind of glitch that was totally not his fault, they came through in the amounts of $5,000 and $1,700.

- Or that other time that a bomb threat on the London Underground blocked access to his offshore account. (Even Spano snorts at this one, claiming he doesn’t remember it, and asking the director, “Did they really believe that?” They did.)

- And still that other thing where decided to “come clean”, telling a reporter that his money was tied up in dealings with a now-dead mobster.

- The audacity: “I probably would do it again. I mean, for four months I owned the New York Islanders.” Spano also cites his father as the one who told him it’s better to have tried and failed than not tried at all. (I’ll pass on the Spano motivational lecture series.)

- The point made by former beat writer Alan Hahn (the best of the film’s many talking heads) when he notes that during Spano's tenure, he was responsible for extending the TV deal that sustained the team for the next nine years. Says Hahn, “He might be one of the best owners in history.”

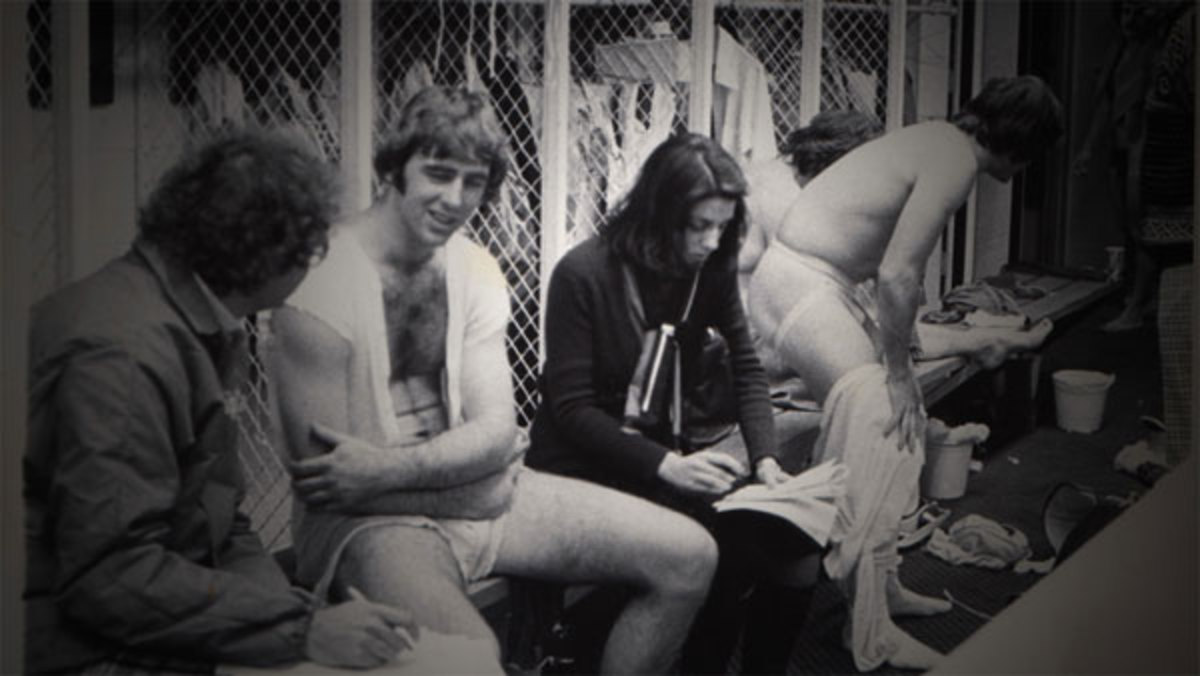

BEST USE OF NAME-CHECKING: Let Them Wear Towels

Directors: Annie Sundberg and Ricki Stern

Jerry Wachter

Part of ESPN’s Nine for IX, Let Them Wear Towels flashes back to the seventies, those progressive years of Glam Rock, Gloria Steinem and John Lennon, the househusband. But as the first wave of women sportswriters would learn, the sports world evolved at its own leisurely pace, and female reporters were barred from entering press boxes and locker rooms—in effect, prevented from doing their jobs. In the post-game locker room scene, the male repoters collected the quotes and anecdotes that colored their stories. On the occasion a woman did get access, she was more likely to end up with stories of chauvinistic displays a player or coach, useless for a game write-up, but ripe for, say, oh, a documentary. Among the indicted:

- Orioles manager Earl Weaver, who kept over his office door a (somewhat baffling) sign that stated “NO WO-MEN.”

- Mets slugger Dave Kingman, who twice dumped water on a female Newsday writer in the clubhouse.

- Hall of fame hockey player Tiger Williams, who shouted slurs at a Daily News writer before physically removing her from the locker room.

Then there were the self-incriminators, like baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who said women in locker rooms wouldn’t be fair to fans who didn’t believe in that (whatever “that” was—presumably fighting to ask your question while sandwiched into a scrum of petulant reporters, breathing in that clammy locker room air); and the Post’s Maury Allen, who rationalized that women sportswriters would “diminish the joy of the sport.” (Pro tip: if you have dumb opinions, don’t state them to the news cameras.) Sitting on the other side of the scale of human decency, players like Steve Garvey and Tommy John were happy to help a sister out. For the most part, though, these ladies fought their own battles with a persistence that eventually made equal access a law.

BEST PLOT THAT READS LIKE A DREAM JOURNAL ENTRY:

Wilt Chamberlain: Borscht Belt Bellhop

Directors: Caroline Laskow and Ian Rosenberg

Courtesy Mark Kutsher

So it was 1954 and there was this freakishy tall guy, a seven-footer—Wilt Chamberlain, actually. But he’s 17 and not yet famous. So he has this summer job at a resort called Kutshers, which is part of this cluster of resorts in rural New York that everyone calls the Borscht Belt and that attracted tons of Jewish vacationers. The owner, Milt Kutsher, was this sports nut and he liked to hire young athletes for his staff. Also he had this employee named Haskell Cohen who worked as the Kutsher’s p.r. guy in the summer, but the rest of the year was the publicist for the NBA. So Wilt worked there as some kind of bellhop, and he was amazing at it because he could use his height to pass suitcases to guests through the second story window. He played basketball too, against teams from the other resorts. Oh, and then Red Auerbach comes out of nowhere to coach this team of bellhops because he's also the athletic director for Kutsher's. Weird, right? Anyway, then it was over. The 8-minute documentary short, I mean.

BEST FAIRWEATHER FAN EXPERIENCE: The Motivation

Dir: Adam Bhala Lough

[vimeo http://www.vimeo.com/63484346 w=500&h=281]

The film is only 85 minutes long, but what Bhala Lough does during that span is impressive. The Motivation begins six weeks before the final event of the 2012 Street League Skateboarding season, an eight-person winner-takes-all championship throwdown. Over the course of six weeks the filmmakers leapfrogged around the globe to document each of the eight competitors, each of whom inevitably revealed a side of himself so sympathetic or charming or heroic that I found myself rooting for a new dude every few minutes.

There was Nyjah Huston, the 17-year-old prodigy whose father bred him to be a colossus of the sport, which of course led to family turmoil. But as the stories change I realize that Nyjah, who won a title in 2010 at 15, doesn’t need this half as bad as Chris Cole, because the 31-year-old Cole has been a pro for 20 years and yet is still winless in Street League. Then there's the kid from Brazil, Luan De Oliveira, the one who was raised by his grandparents in a favela and credits skateboarding for keeping him out of the drug game. But(!!!)—Paul (P-Rod) Rodriguez could lose his sponsorship deals (Nike, Target) if he doesn’t keep producing wins, and he wants to buy a house for himself and his daughter. Or how about the veteran skater from France, Bastien Salabanzi, who needs this win to cement his comeback. And Tiger Beat centerfold/reality star Ryan Sheckler—all he’s asking is for a little respect, man.

It goes on like this until we viewers arrive, conflicted, at the venue, where the competition is exhilarating: the guy I rooted for advances, and the guy I rooted for bails, and when it was over I couldn’t have been more pleased with the winner, because he, too, was the guy I was rooting for.

BEST USE OF AN EXPRESSION THAT IS TYPICALLY HYBERPOLE, BUT NOT IN THIS CASE: McConkey

Directed by: Steve Winter, Murray Wais, Scott Gaffney, David Zieff, and Rob Bruce

Shane McConkey made a lifestyle out of upping the ante. He went from ski racing to freestyle skiing, along the way pioneering a new kind of ski for deep powder and producing some of the most surreal footage in extreme sports. When skiing off ledges got old, he took up BASE-jumping, and when even that felt repetitive he married the two by skiing off a cliff, releasing his skis during free fall and then landing with a parachute. But a life spent chasing risk, as he and the people around him quietly understood, was inherently unsustainable, and in 2009 he died while filming a stunt in the Italian Dolemites. As with any tribute of this kind, McConkey features interviews numerous friends and family members, who are all eager to sing his praises. But when Travis Pastrana, the guy who holds the world record for longest rally car jump (269 feet) calls someone “the most badass person on the face of the earth,” you know that person's legacy is secure.

BEST CLASH OF THE TITANS: Lenny Cooke

Directors: Joshua and Benny Safdie

Lenny Cooke is a heartbreaker. Plain and simple. Granted, it’s just one of countless stories that starts with a young athlete taking bad advice or using bad judgement and ends in squandered talent. Lenny, though, was the premiere high school talent of 2001. During his junior year, on a list of recruits that had names like Carmelo, Amar’e and LeBron, Lenny was at the top. But that summer the landscape shifted at the Adidas ABCD Camp. It was there that Cooke went head-to-head with LeBron James—and while Cooke rocked the future king with a string of flashy crossovers that riled up the crowd, James outplayed Cooke in every other aspect. When James hit a shot to win the game, all the big-talking Cooke could say was, “Oh my God.” A year later Cooke, a high school senior, declared for the draft, but no team bit.

New York Times