There's No Time Like the Present for Floyd Mayweather Jr. to Sell Out

Chelsey Boehnke | chelseyboehnke.com

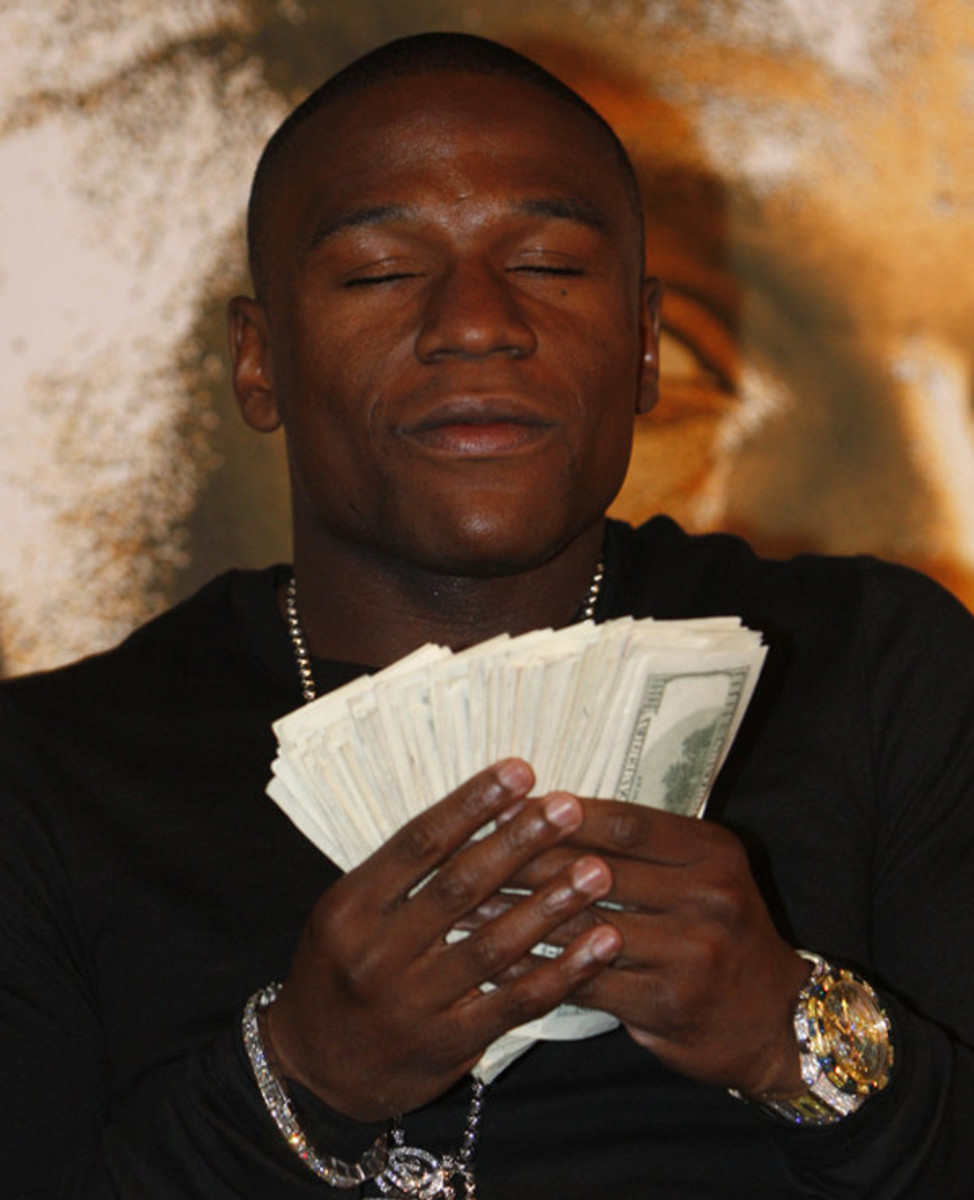

Floyd Mayweather Jr., who for the second straight year topped Sports Illustrated's list of the highest-paid American athletes, generated $90 million in earnings last year -- with an in-many-ways-more-remarkable $0 coming from endorsements. Let that simmer. Mayweather is one of the most popular sportsmen on the planet, on the level of a LeBron James or Lionel Messi in prestige, but one of the least-marketed away from the ring. There has never been an athlete so well known that hasn't parlayed his fame into an easy paycheck.

It's one of the many contradictions at the center of an figure who is at once enigmatic and overexposed, insecure and cocky. For years Mayweather has sold a decadent lifestyle, connecting with the urban market like no fighter since Mike Tyson. His candor and authenticity are unmatched by any other elite athlete, and he can wear, say and do whatever he pleases—a freedom that makes him singular among his Fortunate 50 brethren. That autonomy is a product of his corporate free agency—he is beholden to no one or thing—and offers plenty of value, particularly when it comes to selling PPV buys. But as Mayweather enters the twilight of his fighting career, and the terminus of his fight-related revenue stream comes into view, one thing becomes clear: the world's richest sportsman might want to start worrying more about his money.

When evaluating companies and their business models, financial analysts look at pricing power—the ability to raises price and still get customers to buy a given product or service. For most of his career Mayweather has had significant pricing power—the PPV price of his 2006 bout against Carlos Baldomir was $49.95; seven years later, his May 4 fight against Robert Guerrero cost $69.99 for HD—but there are signs that power is fading. HBO couldn't come to terms with him, so he signed a six-fight deal with Showtime that could be worth a ton, but is largely dependent on his performance and reportedly laden with outs. He's never seemed more rattled than when he was complaining about the HBO negotiations in the recent documentary 30 Days in May; behind the bluster and anger, he basically admitted he's losing his leverage. Showtime is fine, but in the long run how can Floyd the businessman regain that power—especially once he is no longer in the ring? If he can't reach a deal with HBO right now, as one of the most popular fighters in history, how does he do it when he is, say, the CEO of a boxing promotion company, and his fighters aren't nearly as accomplished or widely known?

AP

This might be less of a concern if he were gaining traction with his other ventures, but there's no indication that he is. Mayweather crows a lot about The Money Team, his lifestyle brand, but what exactly is it? Right now there are only a few pieces of apparel for sale on his site, raising questions about whether it's a real company or just the glorified equivalent of a band selling concert T-shirts. The same goes for Mayweather Promotions, which is not a licensed promoter in the state of Nevada (hence Floyd's ongoing relationship with Golden Boy Promotions), and seems otherwise to exist solely for tax advantages.

But while the viability of his businesses may be questionable, the viability of his personality is not. Mayweather is a born showman, and he is fast approaching a point where endorsements make too much sense for him not to pursue them. They provide the greatest payoff from a risk/reward standpoint: you take on no financial risk, and you don't need to dip into your pocket if the business heads south. Consider Michael Jordan and his Nike-affiliated Jordan Brand, or Roger Federer, who is at a similar career juncture as Mayweather but will likely be cashing checks from Rolex for the next 15 years. Shaquille O'Neal, one of the few athletes of the past two decades whose profile, accomplishments and personality outshine Mayweather's, seems well-positioned to thrive as a spokesperson in his retirement. (Which is to say nothing of the potential for Mayweather, who clearly fancies himself a hands-on businessman, to forgo paychecks in exchange for equity in a company he endorses, a la David Wright's arrangement with Vitamin Water.)

This all, of course, assumes that the primary factor in his absence from the pitchman roster has been a lack of willingness or need on his part. It could very well be that companies can't or won't pay what Mayweather feels he's worth, or that his antics scare them off. For the entirety of his career, Floyd's brash, lavish lifestyle has facilitated a kind of bizarre Ponzi scheme: the more money he has and the more money he flaunts, the more money he is able to generate through his fights. Though his corporate independence feels like wasted earning potential, it has also counterintuitively empowered his brand.

Now that house of cards is beginning to look wobbly. Mayweather's legacy as a prizefighter is secure: he has spent more than a decade atop an incredibly demanding sport and won championships across five weight divisions. All the while, he's done things his own way. But that tack is going to become less favorable as the 36-year-old's career winds down. Without a change of strategy, Mayweather's post-boxing career as a businessman may produce the one thing his career as a fighter never has: a loss.

flickr.com