Hall of Fame Voters Take Notice: Steroid Baseball Rocked to the Xtreme

(via baseballcontinuum.com)

“There has been a bit more interest than usual in the annual balloting to see who next will take his place among the immortals of the diamond,” reads an Associated Press story from January 1953. “Burning editorials have discussed the question of whether Joe DiMaggio should be elected now or wait his turn, the upstart. There have been hot words among members of the Baseball Writers Association, whose votes decide the momentous issue.”

DiMaggio, alas, would finish with only 44% of the Hall of Fame vote that year, his first of eligibility, well short of the 75% threshold. In the era before the institution of the mandatory five-year waiting period, many felt odd about enshrining a recent retiree. The BBWAA cared only about Joltin' Joe's place in the baseball pantheon at that moment, not his idol status to so many young fans of the era. And so Joe DiMaggio, who married Marilyn Monroe, who feuded with Frank Sinatra, who practically pissed Fame, finished eighth in a vote for a Hall dedicated to exactly that.

Feeling he should wait more than one year before election, the BBWAA made Joe DiMaggio a third ballot Hall of Famer. That fact is mostly forgotten now. Still, DiMaggio’s Hall of Fame campaign is a tidy reminder that the greatest baseball players are always more important in retrospect. Not yet wrapped in the accumulated gauze of American mythology, DiMaggio in 1953 seemed like just an impetuous “upstart” trying to skip line for an institution not yet fully populated by his baseball forebears. The crusty baseball writers of the time didn’t care what the Yankee Clipper represented to a popular culture they themselves were just barely wafting through.

Now, as many of the steroid era greats miss election again, the modern Hall of Fame debate amounts to not much more than the forgotten DiMaggio controversy of 1953-1955. Withholding enshrinement as a retroactive punishment for steroid use -- like withholding enshrinement as a punishment for being too recent -- will look pointless one day, when players of the Steroid Era are viewed within a proper cultural context.

Mind you, I'm not equating something Joe DiMaggio had no control over to the willful and knowing cheating of the 90s stars. But there's an instructive similarity in the attitudes towards both. After all, Barry Bonds and his ilk really were the DiMaggios of their day, and not just in terms of being best at baseball. Just as Joltin' Joe endures as an American icon of his time, so too were the 90s’ sluggers part of a larger pop cultural milieu.

I should know: I grew up in the Steroid Era, and really, there was no better time to be a kid. That's not garden variety my-childhood-is-better-than-yours sentiment. It's demographic fact. From birth onward, the children of the baby boomers instantly became America's biggest and most important potential dollar. We've been pandered to from the beginning, which is why everything in that period came colorful, juvenile, and X-Treme™.

The timing was a coincidence, but the baseball played during that time, in the heart of the Steroid Era, was objectively the best ever played. Roger Maris was passed six times over. Barry Bonds produced the three greatest hitting seasons of all time. Ichiro broke 260 hits. Pedro Martinez and Greg Maddux boasted the best ERA+ since the Deadball Era.

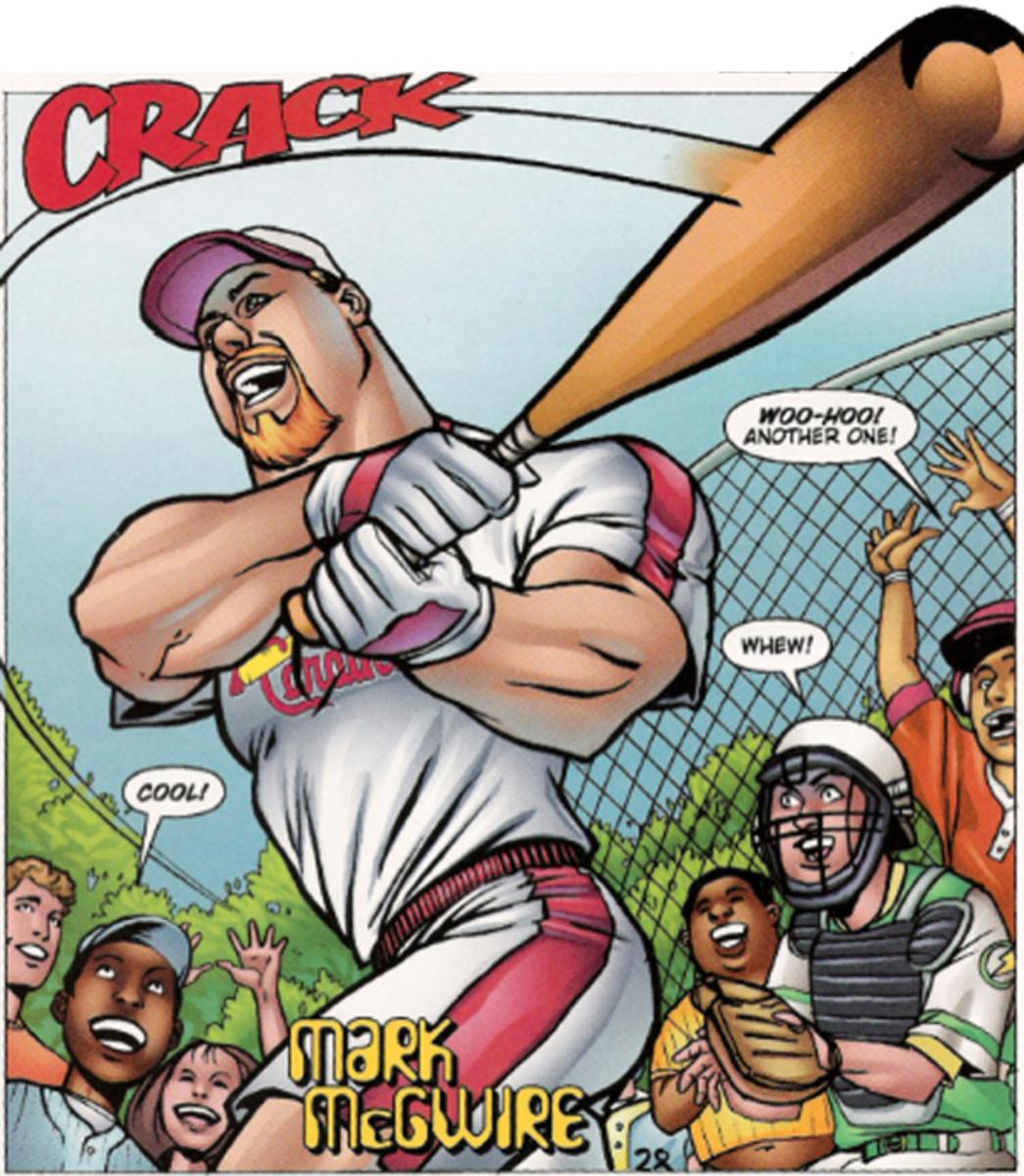

But the way it was better -- not necessarily with superior athletes, but with absolute monsters hitting dingers and racking up strike outs -- was every kid's dream. Hulking superhuman behemoths swung giant bats and hit the ball 500 feet. Young, stupid, and before YouTube, there was no reason for us to think baseball had ever been anything less. After all, when we changed the channel from watching baseball players on steroids, what did we see? Sharks on steroids. Gargoyles -- of all things -- on steroids. We turn on our N64, and waiting for us are NFL players on steroids.

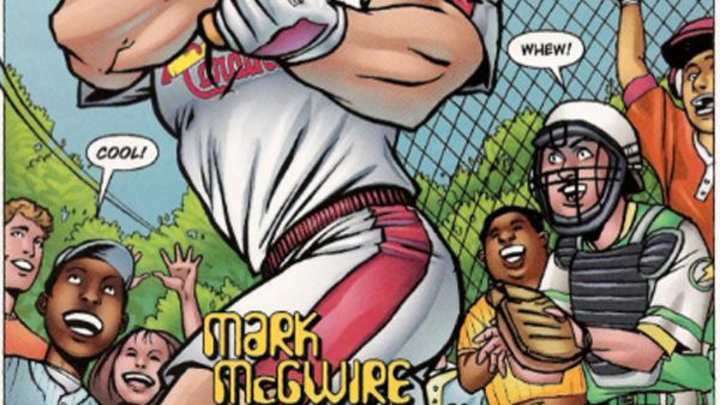

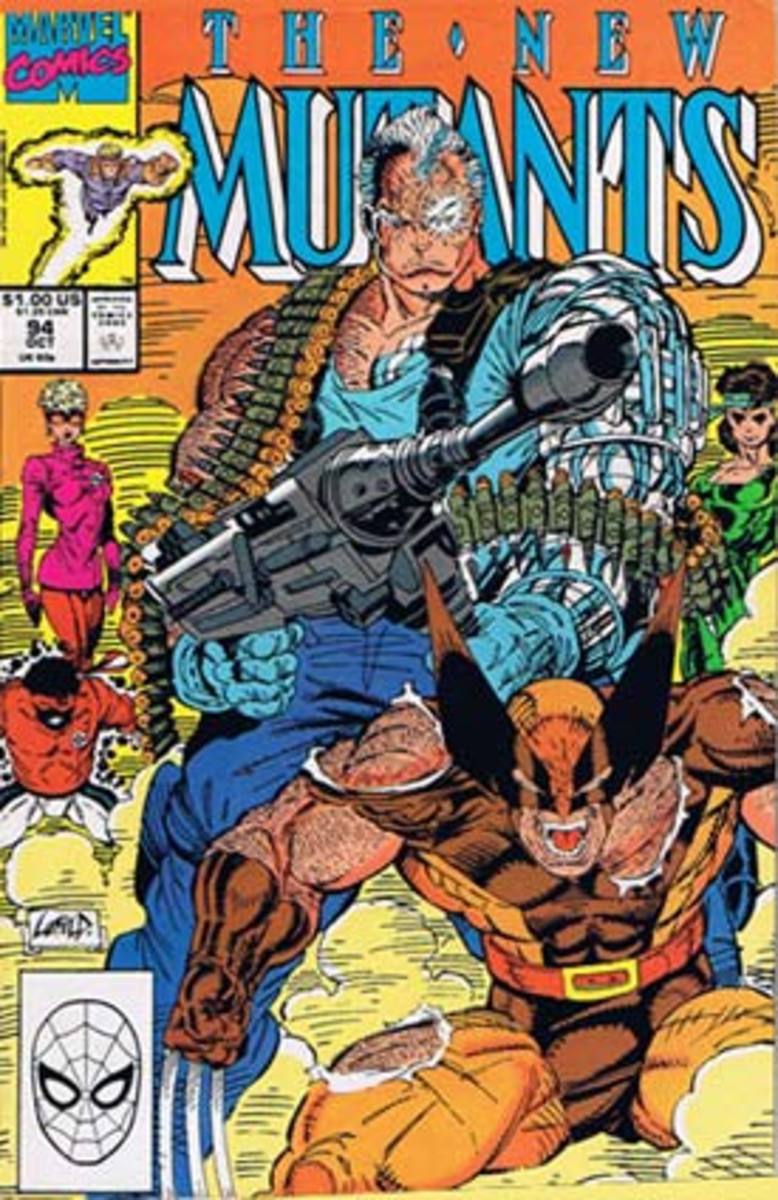

Turning off the TV and going up to our rooms wasn't much of a reprieve either, provided we had comic books. Once a team of lithe heroes in spandex, the X-Men of the 1990s morphed into a revolving cast of BALCO regulars. Lead by Image Comics luminaries like Rob Liefeld, the chosen comic book aesthetic of the time was trunk-like arms, scowling faces, and superfluous body armor.

Shared design practices subliminally strengthened the connection. The comic book and baseball card industries started to cash in on many of the same tricks, creating bubbles of false "collector's items" with endless embossing and chroming. Logos and mascots got meaner and harder. The Toronto Blue Jay flexed his bicep. Pittsburgh’s Pirate was as mad as the Hulk.

This was the era in which "on steroids" meant better. The Hummer, the car on steroids. Supersize, the french fry on steroids. Barry Bonds, the slugger on steroids.

Culture has since moderated across the board for the better. Comic books feature a variety of unique and evolving art styles. Big budget films don't need Schwarzenegger attached to get green-lit. Fielding is important again.

And yet, as the distance from that gaudier age grows, no according perspective seems to follow. Why can't baseball's PED years be viewed as a self-contained moment in time? The great players who were not elected today were perfect reflections of a given era, one which baseball's alleged historical museum of record can't ignore forever.

Sure, the steroid group is an exceptional case. Joe DiMaggio was guilty only of being young. Barry Bonds and Mark McGwire and the rest did something taboo and constantly lied through their teeth to cover it up. You can argue about Gaylord Perry or baseball not officially banning steroids, but the outright shame of their users seems to suggest steroids as apart of baseball's long and whimsical history of cheating.

And yet would this debate even exist if the arbiters of the Hall of Fame were not the same people best position to expose the problem in the first place? The Baseball Writers Association of American isn't exacting a just punishment, it's living a fantasy, building a baseball museum for an alternate universe in which they ruined the careers of the users with scathing exposés, years before records were threatened. They're remaking Cooperstown to reflect the dark, depressing time they believe the Steroid Era to be.