30 Years of NBA Dunk Contest Tweaks: All the Rule Changes, Gimmicks, and Bad Ideas

Desmond Mason going up for a dunk in the 2001 contest. (Photo by Andrew D. Bernstein/NBAE via Getty Images)

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the first NBA Slam Dunk contest. Considering that even diehard NBA fans would concede that the event has only been "good" maybe eight times during the course of those three decades, it's pretty amazing that the contest has survived this long.

In the pursuit of capturing that rare lightning in a bottle—and not just Darrell Armstrong in the air—the NBA keeps tinkering with the format. Ben Golliver already took stock of the significant changes that await dunkers this year, but how can we assess where we are without remembering where we've been? Here's a look back at three decades of oft-misguided innovation.

Never forget the dunk wheel.

1984

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O6E6gSPbkt8

The beginning. The peak?

The contest involves eight competitors and five judges, who score each dunk on a scale from 1-10 (this will be one of the few constants over the years). The competitors (including Julius Erving, Clyde Drexler, Larry Nance, and Dominique Wilkins), are given three dunk chances, and have 24 seconds to complete each slam. If they botch their attempt, the most points they can get is 5. The four players with the highest totals move on to the semi-finals; they have to dunk an additional three times. The contest ends in a showdown, where the last two men standing are again asked to rise up for three dunks. Whoever earns the highest score out of a possible 150 is crowned the champion.

Most noteworthy (other than the wonderful simplicity): Back in the day, players had to successfully dunk the ball nine times without screwing up if they wanted to win.

1985

Change: Defending finalists get a first-round bye

The previous year's last two men standing, Julius Erving and Larry Nance, receive a bye that vaults them into the second round. Additionally, the semi-finals feature five men instead of four.

1986

5-foot-7 Spud Webb, pictured center, won it in 1986. (Photo by Andrew D. Bernstein/NBAE via Getty Images)

Changes: Fewer dunks in a contest that is centered around them; Failure is forgiven; Just one bye

Now only the reigning champ, Dominique Wilkins, gets a bye into the second round. The dunking expectations are lowered, too—competitors have to complete just two dunks in the final round, though the total needed to win is still a whopping eight. A rule change is enacted that allows competitors to fail twice on a dunk per round, which—as we'll see—establishes a dangerous, dangerous precedent.

1987

Changes: Dunks-per-round quotas reshuffled; Good-bye, byes

Competitors now have to perform two dunks to complete in the first round, three in the second round, and three in the third round. Spud Webb—who won the event the year before—does not compete, and so no bye is awarded. Whether or not it was decided at the time, this is the end of the first-round bye.

1988

Changes: None

Ron Harper pulls out due to an injury, so only seven men compete. Otherwise, the rules remain the same. Michael Jordan outdunks Wilkins by two points to win his second and last dunk title. The '88 contest is widely considered the pinnacle of the event's existence. Not coincidentally, it is Jordan's last appearance.

1989

Change: Eschewing integers in scores; Further tweaking of dunk quotas; Accepting less failure

Inspired by the previous year's photo-finish, judges are now allowed to add decimals to scores. The number of dunks needing to be completed in the second round is also reduced to two. Kenny "Sky" Walker wins with a final round total of 148.1 out of 150, though no player gets a 50 on a dunk in any round. The number of dunks a competitor is allowed to miss is reduced to one per round.

1990

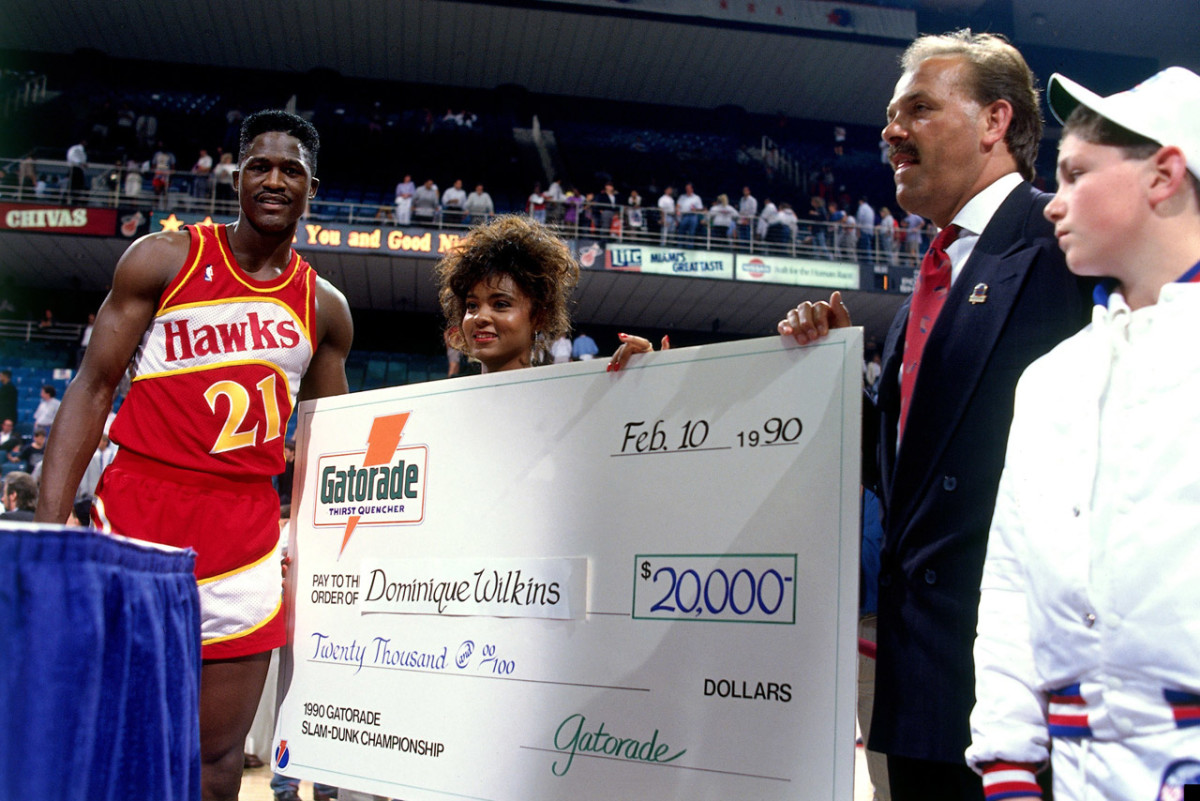

Wilkins earned a huge paycheck (literally) for winning it in '90. (Photo by Andrew D. Bernstein/NBAE via Getty Images)

Changes: None

The event stays the same, with Wilkins squeaking by Kenny Smith to win by 1.7 points. Once again, no 50 is a awarded on a dunk, though Wilkins does earn a 49.7.

1991

Change: Adjusting final round format

The two finalists are asked to throw down three dunks, but their lowest score is thrown out.

1992

Cedric Ceballos' famed blind dunk. (Photo by Nathaniel S. Butler/NBAE via Getty Images)

Change: Fewer competitors

Only seven men compete. Cedric Ceballos wins the event, and in the process receives the first 50 in four years by performing a final round dunk while wearing a blindfold.

Assorted dunk contest historians have, of course, questioned the authenticity of the dunk.

1993

Change: Saying adios to the second round

Shawn Kemp pulls out with an injury, so again there's only seven competitors. Also dropping by one is the number of rounds in the contest. The challengers are given three dunks to compete in the first round, with their lowest-scoring dunk not factoring in the totals. The three dunkers with the highest two-dunk tallies move on to the final round, which has the same format: Best two out of three dunks are used to determine total score.

If you find this format unusual, don't worry. It'll be completely abolished just a year later.

1994

Change: Figure skating-style judging

The format is altered to an extent that renders it almost unrecognizable, leaving the dunk contest a decaying husk of its former self. Now there are two rounds and six competitors. The dunkers get 90 seconds in the first round to complete a minimum of three dunks, and are judged by the totality of their "routine." Three men advance to the final round, where the clock is no longer a factor. The dunkers are given two chances to complete a dunk. Isiah Rider wins, with his two final round dunks registering a 49 and a 47 respectively.

1995

Change: Final round gets a time limit

The format stays roughly the same, with the difference being that in the final round, the three dunkers are given 60 seconds to dunk at least twice; they are gauged on the entirety of their routine. Harold Miner wins for the second year (1993 was his first), beating out luminaries such as Isiah Rider, Jamie Watson, Antonio Harvey, Tim Perry, and Tony Dumas. The days of A-listers such as Jordan, Wilkins, and Erving competing in the dunk contest are a distant memory.

1996

A clean-shaven Brent Barry. (Photo by Nathaniel S. Butler/NBAE via Getty Images)

Change: Low-scoring dunks don't count

In the final round, the competitors are given two dunks to complete, with only their highest-scoring one counting. Brent Barry becomes the first and only white guy to win the event by jumping from the free-throw line.

1997

Changes: No more decimals; No more clock; More adjusting of dunk quotas

The decimal system is abandoned, bringing judges back into the glorious realm of round number. But that's nothing compared to the larger changes: The clock is removed from both the first and second rounds, and the six competitors are given three—and only three—attempts to complete a dunk in the first round; they are judged on their total three-dunk score. In the final round, the competitors are given two dunk attempts, with only their higher score mattering. The winner is none other than Kobe Bryant, who takes home his first and only Slam Dunk crown.

1998-1999

The Dunk Contest is retired from All-Star Saturday activities. In the years between the '97 Dunk Contest and the event's return in 2000, Seinfeld airs its final episode and Batman & Robin hits movie theaters. These are dark days indeed.

2000

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oHMWMh--Tp4

Changes: Existence; Teammates must help

The Slam Dunk Contest was only mostly dead! The event returns, again with six competitors and two rounds. The dunkers have to complete three dunks in the first round, with at least one of them being assisted by a teammate. The lowest score of the three is dropped, and the three dunkers with the highest totals move on to the final round, where they're given two dunks and are judged on their total score out of 100. The event is highlighted by Vince Carter, who puts on a draw-dropping performance.

Vinsanity was so awesome in this thing that, for the briefest of moments, the Slam Dunk Contest actually resonated with casual sports fans, which it hadn't done since the late '80s. If not for Carter it's possible that the Dunk Contest's resurrection would have been short-lived, especially considering the horror shows to come.

2001

Change: Altered scoring system

Vince Carter doesn't return, leaving in his substantial wake six young players who have virtually no name recognition. The dunkers are given two dunks in the first round, with both dunks factoring into their score. The three dunkers with the highest scores move on to the final round, where the scoring format remains the same. Believe it or not, this is the first time that the first and final rounds have had the same scoring system, which seems to make sense. I mean, confusing formats should be avoided right?

Well …

2002

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3v-lij6N0Z0

Change: A giant wheel

All the goodwill that was accrued in the 2000 event is punted, hard, as the Slam Dunk Contest doesn't just jump the shark—it also steals its lunch and gropes it in front of your grandparents. The number of competitors is reduced to four, who are divided onto sides of a small bracket. In the first round the competitors produce three dunks (one of which has to involve a teammate), with their two highest scores determining who goes to the final round.

And in both rounds, they had to spin the Dunk Wheel.

The slots on the wheel corresponded to various slams from Dunk Contests past—Michael Jordan dunks, Julius Erving dunks, "Dunks from the 90s"—and the contestants would have to recreate whichever dunk they landed on. It effectively stripped a degree of creativity from the event, while also implicitly reminding everyone involved—dunkers, judges, fans—that the Dunk Contest was far better in a bygone era. The results were predictably weak, and both the Dunk Wheel and the bracket system were discontinued after one year.

2003

Change: Wheel mercifully goes away; Failure permitted once again

The number of competitors stays at four, but the rules revert to the sensible approach of the 2001 event. For the third straight year the competitors are comprised of young nobodies, prompting Sprite—the official sponsor of the event—to rebrand it accordingly: "The Rising Stars Slam Dunk Contest," a moniker it will sport for a few more years. Competitors are only allowed to mess up one dunk per round. Jason Richardson wins for the second straight year.

2004

Changes: None

The rules stay the same, though the contest suffers from a meh cast that includes Jason Richardson, Ricky Davis, Fred Jones, and Chris Andersen.

Andersen, it should be noted, completed both of his dunk attempts without issue. Put that fact under your mohawk cap.

2005

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Hjg8IXSzWk

Change: Infinite mulligans

A rule change renders the event even more unwatchable than usual: Competitors now get as many attempts as they need to complete a dunk, and it takes Birdman nine tries to pull off his first dunk, and another six goes to land his second dunk. We now exist in a world in which competitors are permitted—encouraged, even—to attempt dunks so difficult that it takes them a half-dozen times to get it right.

2006

Changes: None, somehow

Same rules. The diminutive Nate Robinson is awarded the trophy over Andre Iguodala in a blatant example of favoritism, as Robinson needed an unreasonable 14 attempts to complete a single dunk.

That a person who needs 14 tries to land a dunk is not deserving of a dunk title should be self-evident.

2007

Change: Dunk time limit enacted

Common sense prevails, albeit in small doses. The stench of Andersen and Robinson is so great that a rule is changed, and now the amount of time a player has to complete a dunk is reduced to two minutes. Yet this still proves too lenient, as Robinson uses the full time allotment in a futile attempt to pull off the coolest dunk in the history of modern civilization.

2008

Change: Text message voting

Power to the people! The final round is no longer decided by the judges, but instead by the fans via text messaging. 78% of the viewers award the title to Dwight Howard. Progress?

2009-2011

Changes: None

For a few years the event remained the same, and its level of watchability was tolerable—notwithstanding what was clearly a Kia-orchestrated appearance in the 2011 finals for Blake Griffin.

And then, disaster.

2012

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fdDvweqtci8

Change: No more traditional scoring

Worst. Dunk. Contest. Ever. (Not that the 2013 contest wasn't horrible too, because it was—oh, it was—but the 2012 contest takes the event to a low that was once thought unimaginable.)

The rounds system is abolished and the four competitors—Derrick Williams, Chase Budinger, Jeremy Evans and a then-unknown Paul George—are given three dunks to complete. Judges are removed from the equation, with viewers deciding the winner via text messaging voting. Also—because, why not?—Sprite introduces a "Dunk Intensity Meter" that claims to measure the forcefulness of each dunk, except the readings prove to be so erratic that the meter loses meaning almost immediately. Meanwhile the competitors are unspeakably inept, with each player messing up at least once, and often over and over and over again. Jeremy Evans wins in the voting by 1%.

By the end, Reggie Miller commented on TNT: "I'll take a lay-up right about now."

2013

Change: Judges return

Following universal acknowledgment that the 2012 contest was a trainwreck, the format is restored to its previous version, with judges ruling on the first round and texters determining the champion. This time, the number of competitors is increased to six, which just meant that two more players would be contributing to the uncomfortable, embarrassing barrage of missed dunks and broken dreams.

At the beginning of the telecast, Kenny Smith tries to breathe life into the contest by predicting: "This is going to be one of the top 10 Dunk Contests of all time."

The event turns out to be so bad that in the middle of it, Shaq and Charles Barkley ask Smith he's standing by his prediction.

Smith lifelessly replies: "I've been wrong a couple times in my life. That might be one."