Patriotic spandex and giant Q-tips: An oral history of American Gladiators

Thirty-four years ago an ironworker named Dan Carr and an Elvis impersonator named John Ferraro took over a high school gym and put on a fundraiser production for the people of Erie, Pa., originally called King of the County. The show was a Rust Belt rethinking of the coliseum spectacles of ancient Rome, in which strong men fought to the death for entertainment’s sake.

The locals who accepted this challenge were far from mythic. They were electricians, truck drivers, car dealers—anyone who would savage his neighbor for $500. The feats of strength in which they engaged were crude: arm wrestling, tug-of-war. . . . The whole thing was set to music; 5,000 people showed up.

Ferraro had the good sense to hire a camera crew, as he hoped to sell the idea as a movie. (Carr bowed out.) But when he finally got in front of Hollywood macher Samuel Goldwyn Jr., Goldwyn told Ferraro that what he had on his hands was a much smaller production, something that would work better on TV.

For seven seasons American Gladiators—revised to pit Average Joes against a team of superfit pros—enthralled a curious nation with its star-spangled spandex onesies, campy stage names, blow-dried personalities and punishing hits. When Bill Clinton copped to watching the show, it went from being a fratty, ironic viewing choice—“Star Search for the working man,” Ferraro calls it—to a metaphor for exceptionalism.

This is the story of a cult hit, told by the people who powered the ratings machine, from its inauspicious start in 1989 through its conclusion in ’96.

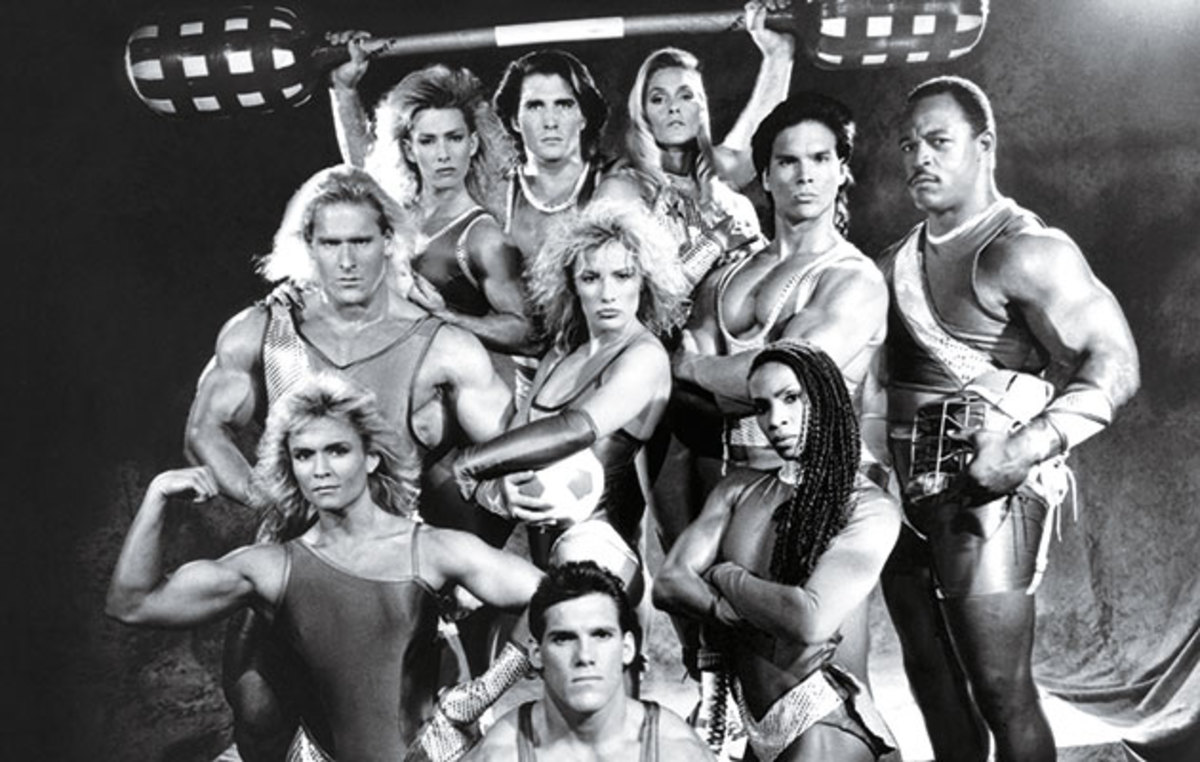

American Gladiators Now and Then

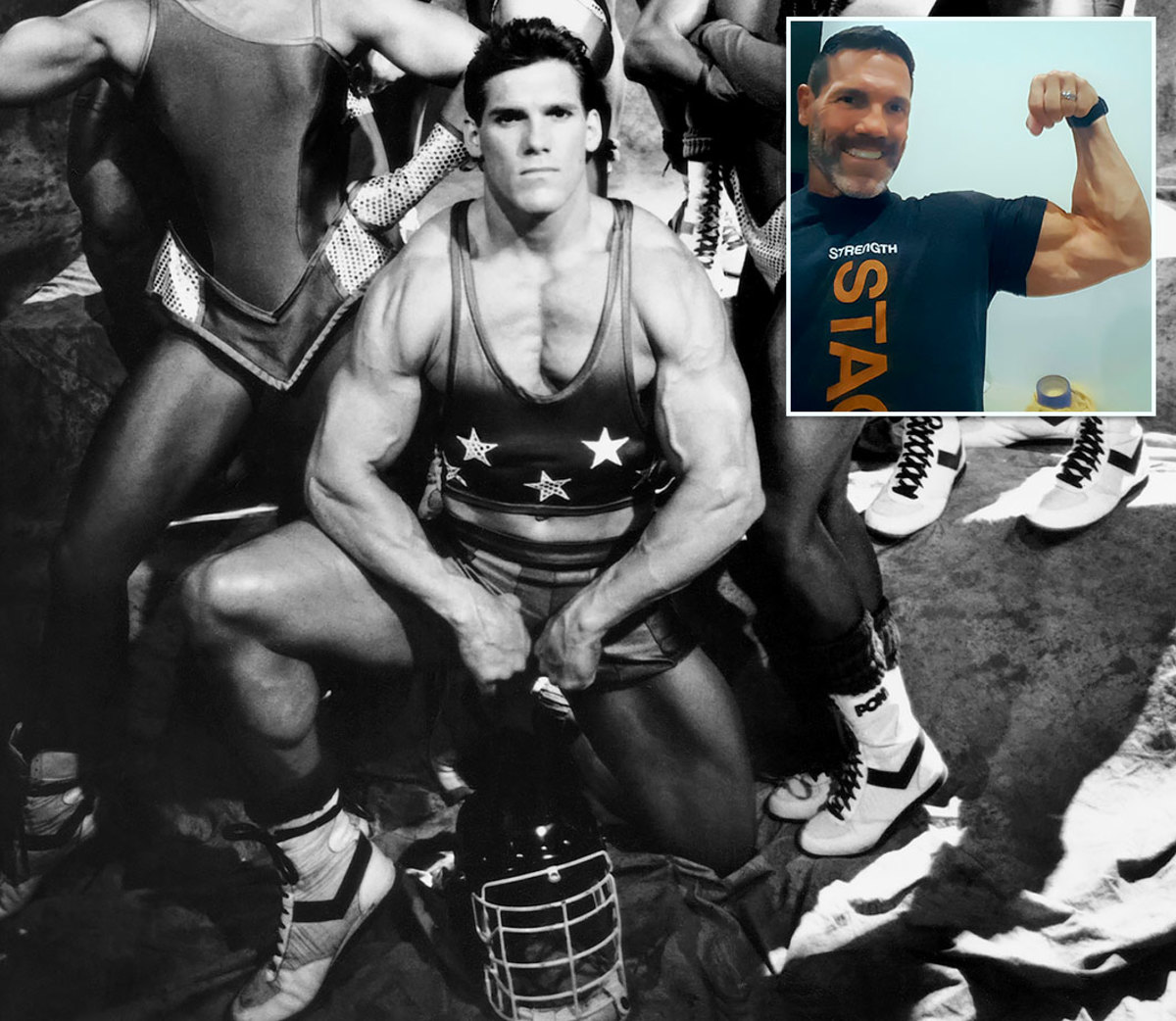

NITRO (1989-92, '94-95)

Seven years after publishing his first book, Gladiator, about his life in the limelight, Dan Clark is working on a second book, Cultivating Happiness, about life after a heart attack. He is also the brains and brawn behind Gladiator ’N Run, a 5K fun run through the California mud.

LASER (1989-96)

A pioneering fitness pitchman for companies like 24-Hour Fitness and Apex, Jim Starr s the director of product development for Life Time Fitness, a Minnesota-based chain of high-end gyms. Hearing his then one-year-old daughter calling for him over the cheers of the studio audience remains his proudest moment on Gladiators.

BLAZE (1989-92)

If you live in the Bellflower, Calif., area and are a parent to a student in grades K through 12, there’s chance Sha-Ri Pendleton-Mitchell might turn up in their classroom to substitute teach. After the final bell, you can find her on the track at St. John Bosoco High, coaching a track team that includes her son, Re-Al, a promising sophomore sprinter.

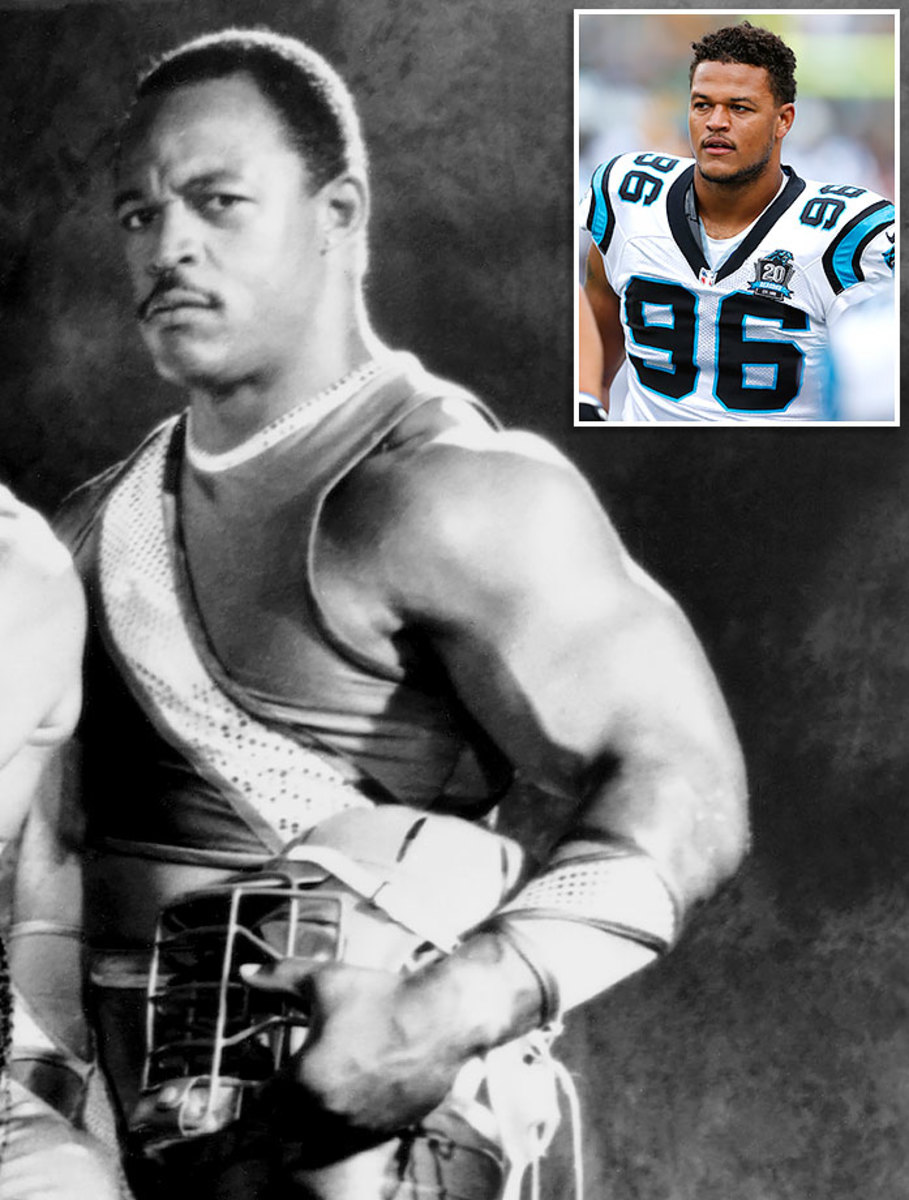

GEMINI (1989-92)

Michael Horton works as a physical fitness consultant in the Los Angeles area. The youngest of his three children, Wes (inset), a fourth-year defensive end with the Carolina Panthers, can’t remember much of his experiences visiting the Gladiator set as a three-year-old.

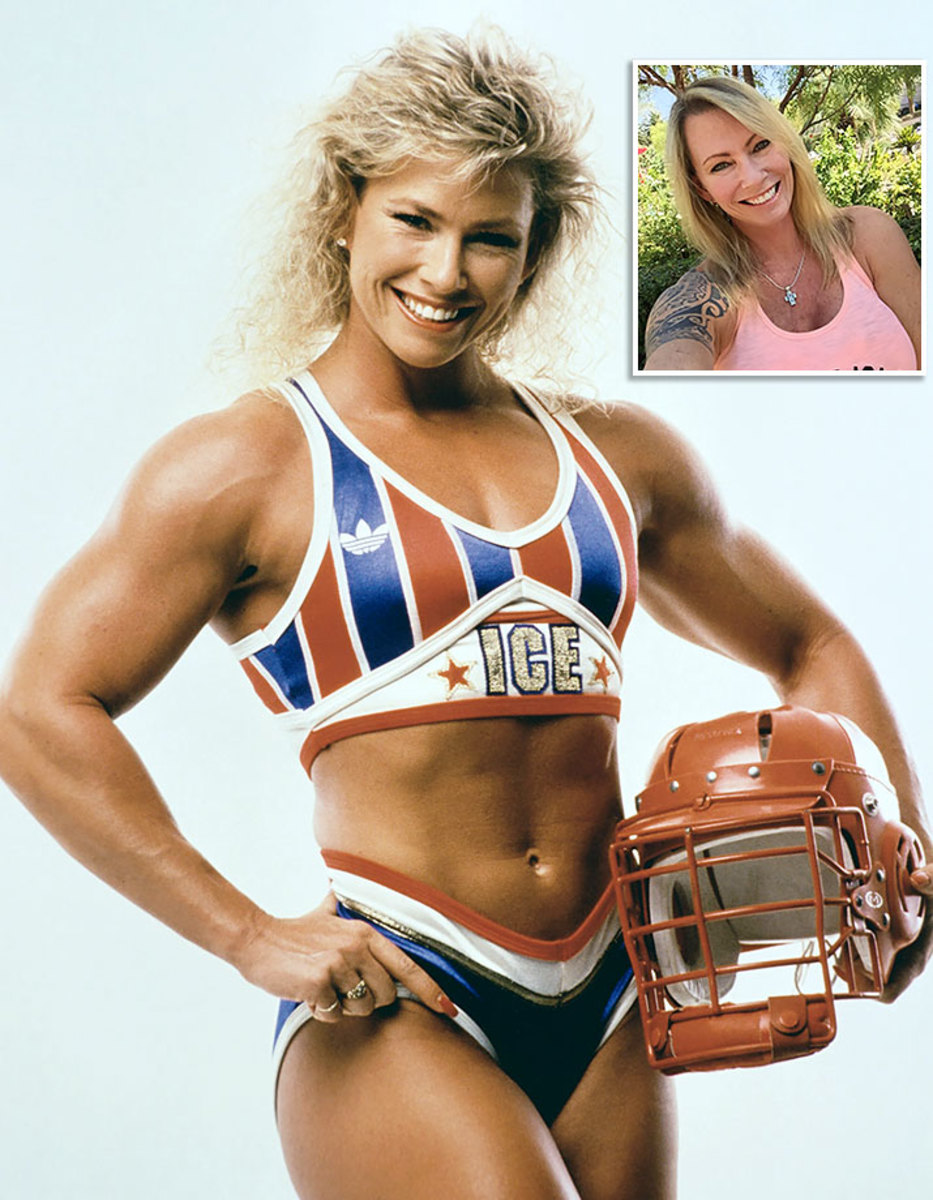

ICE (1991-96)

When Gladiators was at its peak, Lori Fetrick made guest appearances on everything from Who’s the Boss? to Ellen; now she travels the country conducting seminars on health and financial wellness.

MALIBU (1991-92)

Batman Forever and Mortal Kombat: Annihilation are just a few of Deron McBee’s film credits. He’s gone from playing comic book characters to using markers, color pencils and watercolors to render them while working avocationally as a graphic artist.

SABRE (1993-96)

Red Williams parlayed his Gladiators fame into a starring role as Jax in the 1997 box office hit Mortal Kombat: Annihilation. These days a married father of two and grandfather of three, Williams teaches scripture in the San Pedro, Calif., area.

DALLAS (1994-98)

After successful post-Gladiator forays into boxing and wrestling, Shannon Hall now trains MMA fighters. She’ll be in Kenia Rosas’s corner for her pro debut against champion judoka Mackenzie Dern on July 22.

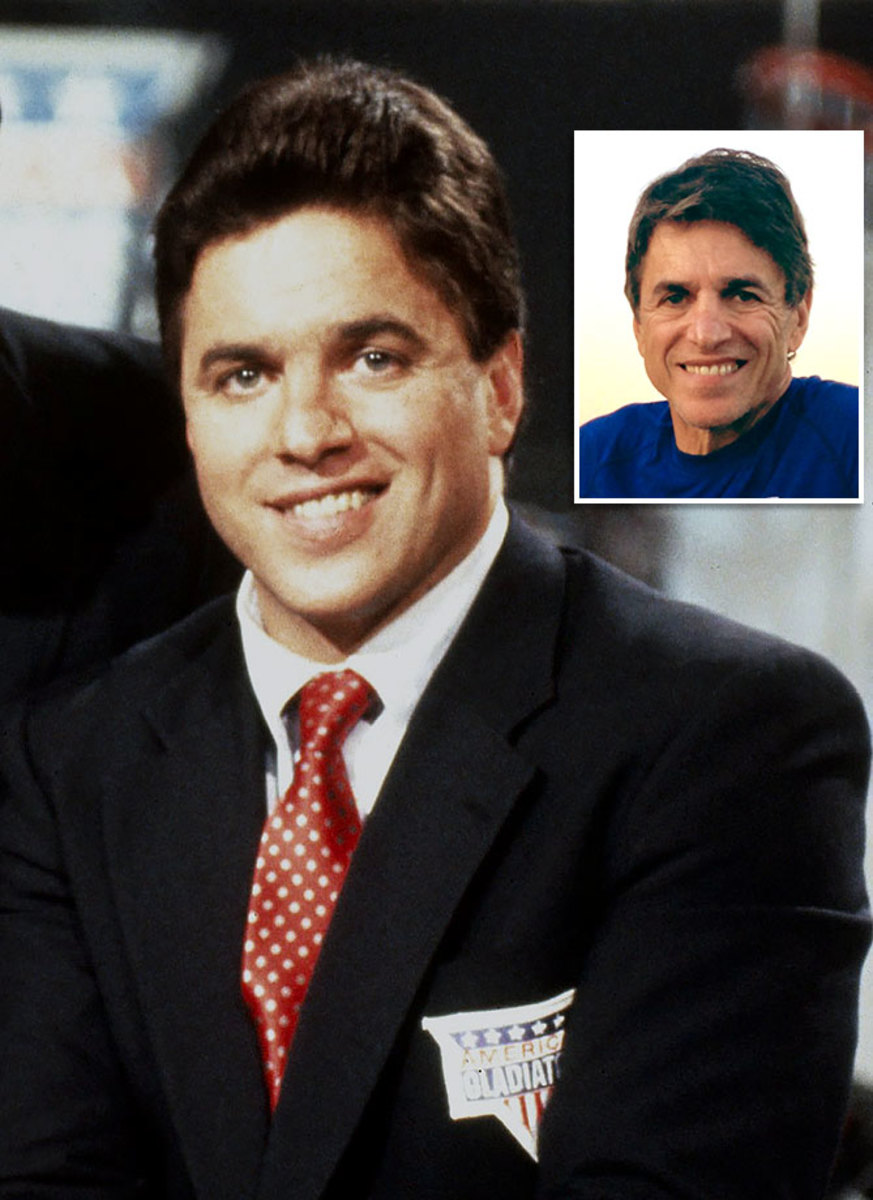

MIKE ADAMLE (1989-96)

Adamle is a mainstay at NBC 5 Chicago, where he’s the sports director and an anchor. Like many of his fellow cast mates, he still works out like a fiend and confesses that sometimes he wakes up in the middle of the night in a cold sweat, singing the Gladiators theme song.

JOHN FERRARO (1982-present)

He doesn’t impersonate Elvis nearly as much as he used to. He’s determined to revive the Gladiators franchise and make it everlasting.

RAW MEAT

Michael (Gemini) Horton, gladiator: Before Gladiators, I played football for the Patriots. I was trying to make the transition from athlete to actor.

Dan (Nitro) Clark, gladiator: I’d just finished playing pro football with the L.A. Rams and then in Italy. I’d moved to Hollywood to be an extra on the HBO show 1st & Ten, with O.J. Simpson. I didn’t know what an extra was back then—all I knew was that I would be playing football on TV for $125 a day. I thought that if you were on TV then you were famous and automatically hanging out with Sylvester Stallone and Eddie Murphy; I didn’t know I would be the lowest guy on the totem pole. When that job ended, I couldn’t accept the failure. I’d seen O.J., Lawrence Taylor and Roger Craig on that show. And while those guys would’ve crushed me on the field, they couldn’t touch me on camera. I had a certain chutzpah that they didn’t. Then, right when my Hollywood dream was running on fumes, I heard about a show that was looking for athletes who were good in front of the camera.

Deron (Malibu) McBee, gladiator: I was working as a personal trainer when the guy riding the Lifecycle next to me saw that casting ad in the trades and said, “Dude, this sounds like you!”

Gemini: The audition in 1988 was in L.A., at Lake Balboa Park in the Valley, but I was about two hours late because I couldn’t figure out exactly where it was. Finally, I stopped at a store to get a six-pack of beer and some peanuts—I was done looking for that thing! But then two really fit girls in athletic clothing walked in and I asked them if they had been at that audition. They said, Yeah, and they told me where it was. The people who showed up were overweight, some with knee braces on. . . .

Nitro: When I tried out they had us do these stupid football drills.

Gemini: . . . and from that big group they narrowed it down to 12 people—six guys, six girls. Then six—three guys and three girls: me, Nitro and Malibu; Zap [Raye Hollitt], Sunny [Cheryl Baldinger] and Lace [Marisa Pare].

Nitro: They had us pick from a bunch of character types—double personality, babes-and-waves, loud and cocky. I chose the last one; they’d originally named that character Evander, but I came up with Nitro. They put us on camera and asked us questions in character. They asked me what I ate and I said, “raw meat.” What a tool I was.

THE BURNING BUSH

Gemini: We shot the pilot at the Los Angeles Equestrian Center near Burbank. It was horrible. We got paid $500 for the day and they kept us there from 9 one morning till 4 a.m. the next. The things they had us doing were ridiculous, all these games rigged up to give it the aura of a sports competition. There was horse manure everywhere—the space was usually used for riding—but that wasn’t the most unbelievable thing. That would be Johnny Ferraro; he was always dressed like Elvis. Always. And the whole thing: glasses, scarves. . . . He walks into our trailer . . .

John Ferraro, co-creator and executive producer: They were in a small, little room.

Gemini: . . . and he says, “I’m Johnny Ferraro. I own the show. And you guys are all gonna be big stars.”

Ferraro: It was almost like when you see the burning bush. I mean, I saw this thing. Even though I had only done the one small event in Erie, I saw what American Gladiators could be.

Gemini: All six of us, we’re looking at him like: We just did this s--- in horse manure, played these games that don’t make any sense, and you’re gonna make us stars? And you look like Elvis?! Yeah; good luck, pal.

Mike Adamle, announcer: The pilot was pooh-poohed by Goldwyn [head of Samuel Goldwyn Television], until he saw one event called Assault, where we had gladiators stationed at different air-gun stations, shooting tennis balls at the contestants. In particular, the sight of one of the female gladiators competing in this thing got a big reaction. On that small little moment [Goldwyn] decided we had something.

Ferraro: We edited that tape down to seven minutes and took it, along with the gladiators, to the 1988 National Association of Television Program Executives convention. This was back when syndication was in its day. We signed up stations from all over the country with a 13-episode order. Next thing I know, we’re shooting inside Universal Studios’ Stage 27.

Nitro: During those original tapings we couldn’t get enough people from the studio tour to fill the audience, so they painted faces on planks.

Ferraro: We shot that first order in two weeks, very inexpensively. The production was . . . crude. The “referee” was an executioner—a guy with a black hood giving the thumbs up or down [essentially disqualifying a player after a given event]. I thought, My God, all of these years of work and it all comes down to this?

Adamle: It was a constant evolution, getting the games right, getting the gladiators comfortable with the games, getting the competition to the point where it was authentically exciting. One key guy who put us over the top was our eventual referee, Larry Thompson; he was one of the Pac-10’s top football officials. He spent, like, two weeks coming up with the rules for every single game.

Ferraro: We had pitched the whole thing as a late night show, something that could go up against Saturday Night Live.

Adamle: The producers came away with the idea that our core audience was gonna be males 18 to 35. But by having men competing too, that demographic [grew to include] women. The ages shot up to 55 on the high end, down to 10 on the low end because the Gladiators were basically comic book superheroes come to life.

Ferraro: After a while on the air the show picked up a real cult following and started getting better and better air times. That was enough to get the show renewed.

Gemini: That’s when the budget got bigger.

Ferraro: That’s when we got the set with the big columns. We got announcers from the football world, which gave the show enormous credibility.

Gemini: Todd Christensen [two years after retiring as a Raiders tight end] was great—but, man, what an arrogant dude. Oh my God. Bless his heart, but he just thought he was above it all. He wasn’t enjoying himself.

Ferraro: Fran Tarkenton, Larry Csonka, Joe Theismann. . . .

Joe Theismann, announcer and former NFL QB: Gosh, I haven’t thought about this in 20 years—yet I can picture the outfits they wore, the people that competed. It was fun to be there in the beginning, when we were basically building this thing on the run.

Ferraro: I pushed Goldwyn to put some music behind this.

Adamle: Everybody remembers the theme song—dun-dah-dah-dun-dan-dad-DAH! dah-dah-dah-DAAAHHH!

Ferraro: I had always loved Bill Conti, who scored the Rocky films.

Bill Conti, theme song composer: So they ask me to do the music; the turnaround time was fast. I’m working stream of consciousness, putting in as much noisy brass as I think will make someone want to stand up and punch someone across the river. I send some stuff to the studio through a messenger. Then I call, “Did you guys get it? What do you think?” They say, “Yeah, we loved it—but we’ve got the paramedics here. . . .” I mean, every time I called back about another piece of music it was, “Well, this guy just fell off this thing. . . .” I’m like, Oh my God, I gotta check this thing out.

FROM MANURE TO MSG

Gemini: That first season was really barbaric; we got busted up like you wouldn’t believe. The contenders were smaller than us, but a lot of them were cops, firefighters, ex-Marines, martial arts guys—tough guys with tough spirits. They would film one show a day . . .

Adamle: . . . but we—the broadcasters, the gladiators—would do two or three shows in one day. We’d shoot two seasons in a three-month span.

Gemini: Everything we did involved falling from a great height, 20 or 30 times or more. You’re banging your back, your shoulders, your elbows, your knees. . . . The injuries started mounting up. We needed more gladiators.

Lori (Ice) Fetrick, gladiator: I was bodybuilding at the time, training at Gold’s Gym in Venice when I ran into Zapp. I was like, "How'd you get on that show? Are you doing it again ?" She said. “No, I’m pregnant.” "How do I try out?" “Oh, just watch the show. At the end, they’ll tell you.” Well, they didn’t. Because there was no internet at that time, it took me three months to find the production company and get a tryout.

Red (Sabre) Williams, gladiator: When I tried out, I was working as a marketing rep for a health maintenance firm in L.A.; there were 600 other auditioners.

Ice: They wound up hiring me and Diamond [Erika Andersch].

Sabre: From my 600, they narrowed it down to three: me, another guy and Titan [Mike O’Hearn].

Sha-ri (Blaze) Pendleton-Mitchell, gladiator: I was fresh out of college at Nebraska. I ran track and was training for the 1988 Olympics in L.A. when I strained my hamstring. While I was rehabbing, someone in the gym approached me about trying out for the show. I had never heard of it. Then I told my family. They had seen the pilot; they went crazy.

Shannon (Dallas) Hall, gladiator: I was living in Dallas, bodybuilding and stripping. I was a real wild child. On a dare, I entered a regional tryout to be a contestant. Everybody was super serious while I was really drunk and a little high, laughing about everything, making fun of people. When they called back and asked if I instead wanted to be a gladiator, I was like, I guess the stripping’s gotta go on hold.

Jim (Laser) Starr, gladiator: Nitro and I met at Rams training camp in 1987 and quickly became inseparable. One year after he made Gladiators they had another tryout and I made it. I wound up lasting seven seasons and doing more episodes [127] than any other gladiator. The work was crazy. When a contestant advanced to the next stage, they would have two or three days to recover from any injuries. But we would have to keep going right away.

Gemini: Eventually I told the producers we needed an athletic trainer on set. They let me bring in Tony Spino, who was the trainer at UCLA when I played football there.

Blaze: One time I rolled my ankle playing Breakthrough and Conquer [a combination of wrestling and short-field football]. My foot was so swollen, I thought I was gonna be out for a week. But Tony submerged it in a bucket of ice, massaged it, taped it. It healed in a day. The guy worked miracles. He had to. We couldn’t afford to miss time.

Laser: In the seven years I did the show, I had 11 surgeries. Most of them were for shoulder injuries. If you were hurt on that first day of taping, boy, you had to suck it up—buckle your chinstrap and go. The show didn’t pay a ton of money [$12,000 total for the first 13-episode season, plus 400% in residuals], but still: If you missed an episode, you were gonna lose out.

Dallas: They did have insurance. If you got hurt, they did fix you. You just didn’t get paid while you were out.

Laser: To survive, we iced. We took painkillers.

Nitro: My first day of shooting season three, I herniated disks in my back. After putting me through a battery of tests, the show doctor said, “You’re out for four to six weeks.” I was looking at losing out on hundreds of thousands of dollars. I asked an exec what I needed to do to get back on the field. She said the only way was to get the doctor to sign off. I took a handful of Vicodin, went back to the doctor that afternoon and passed every test she put me through. That season, painkillers and I were good friends. A gladiator has to eat.

Laser: I don’t think any of us gladiators had a sense of where the show was going to take us.

Ferraro: Very quickly, it took on a life of its own.

Gemini: Colleges really bought into it.

Malibu: Guys were getting together for Gladiators parties within months of the show being on air.

Gemini: They started having knock-off gladiator competitions on campuses, especially on the East Coast. They tried to get us to come out to them.

Ferraro: At that point I went to Goldwyn and said, “We gotta do a tour, take the show on the road.” They fought me tooth and nail, so I started putting it together without them. I got hold of a guy named David Fishof, Phil Simms’s old agent, who organized the initial part of the tour. Then we hooked up with Ken Feld, who owns Ringling Brothers Circus—they booked big venues, 10,000- and 20,000-seat arenas. We announced the whole tour at Madison Square Garden.

Gemini: I couldn’t believe how many cameras were there. I look over at Johnny; he looks back and winks—like, I told you so. It was so surreal, going from manure to Madison Square Garden.

BETTER THAN THE OLYMPICS

Ferraro: That tour [from 1991 to ’92] was pretty gruesome. We did 114 cities.

Blaze: That was the best.

Laser: Some of the most fun I’ve ever had.

Ice: Crazy, like being a rock star.

Gemini: We’d start in Maine and work our way across the country.

Laser: It lasted nine months, but none of us were ever traveling for that long. We’d go for three or four weeks, take a break, fly home, visit our families, then join back up with whoever was out there.

Sabre: The big-name gladiators like Gemini and Nitro and Laser, they couldn’t afford to get hurt—those were the guys people came to see. They needed some grunt gladiators to do all the hard events every night on tour. That was pretty much how I got hired.

Laser: They would hold tryouts two weeks before an event to have contestants ready. It was a magnificent feat, taking all that equipment and all those people on the road.

Gemini: We hit every big venue: MSG, Chicago Stadium. . . . If a leg was more than 275 miles, we flew. If it was under, we were on Whitney Houston’s tour bus, which was gorgeous. Every single place we went was a sellout. We would run into MC Hammer at different venues. . . . His crew is breaking down, you’re setting up; you’re breaking down, they’re setting up. Then we went to Europe.

Ferraro: When we had that tour, that’s when everything went through the roof.

Malibu: I booked a regular spot on a studio stunt show, Conan the Adventurer, at Universal. I was running back and forth between shows. It was a magical time.

Laser: The nice thing about the show was that once a season ended, you could take the rest of the year and work other screen jobs or do gladiator appearances. A lot of us did trade shows, made extra money signing autographs. For two years I became a celebrity endorser for a supplement company.

Gemini: I made a heckuva lot of money doing that stuff.

Ice: I got invited to Bruce Springsteen’s house in Hollywood for his birthday party. Immediately, he introduces himself, says he’s a fan and then, “I wanna show you something.” He leads me downstairs to this gorgeous gym. In my head I’m like, You've gotta remember this moment. . . .

Nitro: I remember having lunch at a Hollywood restaurant. Steve Martin approaches my table, introduces himself and tells me he’s a huge fan. Then he brings me over to his table and introduces me to Dustin Hoffman and his wife. The s--- was crazy. One night I was invited to a party at the home of the late billionaire Marvin Davis. Tony Bennett is the entertainment, Cristal is flowing. . . . I’m introduced to former presidents Ford and Carter. As I’m leaving, Merv Griffin tells me there’s someone he wants me to meet. It’s Ronald Reagan.

Malibu: WWF had been killing everything in syndication, and then this little show came along and started slaughtering them. Think about that.

Blaze: No, I didn’t get to realize my dream of representing my country in the Olympics. But, hey, I got the Gladiators! I was still wearing red-white-and-blue, and in my eyes it was better than the Olympics. I ended up getting more recognition than my friends who qualified for the ’88 Games.

Gemini: At the same time, they didn’t want us to become too big. It was always, We want the show to be the star.

Ice: Imagine the producers on Friends saying, “O.K., Jennifer, you’re not the star. Friends, the actual show, is the star.”

Nitro: We took the competition very seriously, but everything else was kinda like the Wild West. We were a bunch of athletes, drunk on fame, fueled by youth.

Dallas: We were all sleeping around. Who wouldn’t be at that time? S---, if that door opens, you’d better walk through it! Some of the gladiators slept with each other. There were no major relationships or babies. It was just, You’re good looking, I’m good looking—let’s get together!

Ferraro: I remember going down to Texas, walking down the street. I’m leading, and behind me are the gladiators. I’m six-foot, but of course these guys dwarf me. People are looking and pointing. Then they start closing in around us, challenging us. Well, you don’t look so tough—that kind of thing. Next thing you know, it’s like, Guys, we gotta go. People saw the gladiators and wanted to test them.

Malibu: We had to stay together. We had to fight together.

YOU DON’T MESS WITH US

Theismann: I felt like I had an intrinsic appreciation for the Gladiators concept because I had competed in ABC’s Superstars, a sports competition featuring star athletes from various arenas—trust me, it was big in the ’70s. I really got into Gladiators; I had some input in some of the events.

Adamle: Joe would go to sleep, come in the next day and say, “Hey, guys, how about this?” There was no such thing as a bad idea. Everybody got to contribute.

Theismann: I even ran through the competitions to get a better sense of what the challengers were going through. I did all kinds of research into their athletic backgrounds. I wanted to be able to tell their stories.

Malibu: We soon realized, these contestants coming onto the show are not playing—they’re out to kick butt. We’re not gonna just dance around in our star-spangled underwear and look great.

Dallas: Once you were in character, you had to bring it. You had to earn the respect and trust of your fellow gladiators.

Malibu: That’s when you saw a team dynamic among the gladiators. It was us against them.

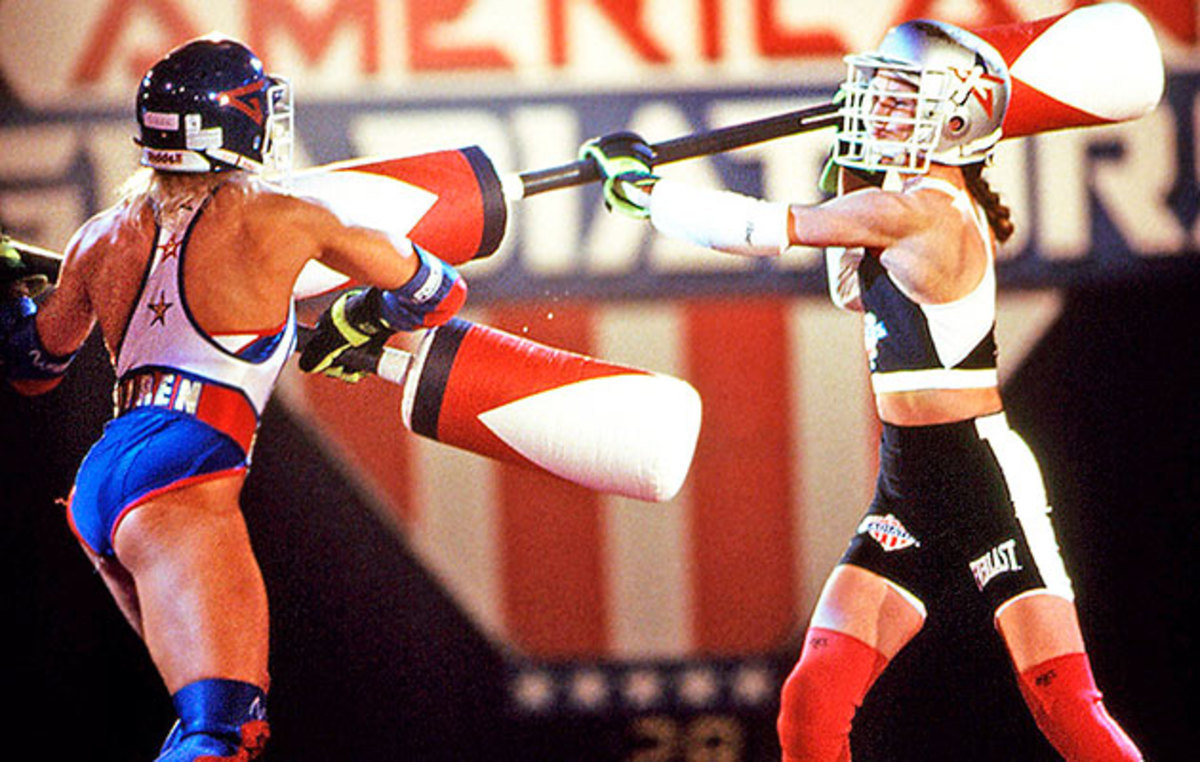

Blaze: The scary part is, we never really rehearsed. At most we’d do a walkthrough to familiarize ourselves with new events. Meanwhile, the contestants got to practice. They were coached by Marines. The first season, they brought up two drill sergeants from San Diego; me and this one sergeant, we couldn’t stand each other. The second season, I asked him for some tips on getting better in Joust [essentially, an elevated pugil-stick battle]. Third season, I went down to San Diego and trained with him on base. Long story short, I end up marrying the guy, Rodney Mitchell. On top of that, he ends up being cast in a rival show called Knights and Warriors. Twenty-five years later, we’re still together!

Malibu: I got a concussion way back on the first day I filmed, and I needed plastic surgery on my forehead. I had to beg my doctors to let me go back on the show; they were saying, “Another head injury and that could be it for you.” Later, I’m wrestling a guy in Breakthrough and Conquer. I point to my stitches and tell him, “Please, just don’t kick me in my forehead.” The second the bell rings, he smacks me right in my stitches. The other gladiators say, “Next event is Powerball [where contestants attempt to deposit balls into cylinders while gladiators oppose them]; Malibu, you drag him off-camera.” Sure enough, I get him off-camera and pound the snot out of him. He comes back on-camera and his uniform is disheveled, his face is red and his hair is tweaked. That was the quintessential, you-don’t-mess-with-us moment. That guy’s name? Billy Wirth; he was in The Lost Boys. Great movie.

Laser: As the show got bigger, they brought in celebrities, pro football players, Olympic athletes to be contestants.

Nancy Lieberman, contestant and Hall of Fame basketball player: The producers called me and said, “We understand you won the all-female Superstars,” which is kinda how I made a living coming out of college. “We’d like for you to come do Gladiators.” The top prize was $10,000. I’m thinking, I’m gonna go over there and kill it. Danny Manning had been on the show too. Serious jocks.

Danny Manning, contestant and former NBA forward: I had a lot of friends that were involved in the show, like Sabre.

Sabre: Danny was one of my best friends at Kansas, where I played college football. When he was being recruited, I was part of his unofficial welcome committee. When Danny went to clubs, he would take my ID and the bouncers would know to take care of him.

Lieberman: We get one day of practice on Gladiators. They introduce us to the gladiators and I go over to one of the girls, touch her bicep. I say, “You’re stronger than my husband,” and she just glares at me. They didn’t know my sarcasm. I’m like, “This Q-tip thing [Joust] can’t be that hard.” Next thing I know, my opponent is snapping my head backwards. . . . O.K., can I try the gerbil-cage thing [Atlasphere]? I can’t get rolling. I try climbing the Wall. They give me a 10-second head start, but I’m halfway up when I feel a hand grab me and rip me off. This is practice. The show was a disaster. I was one of the first eliminated; I took my $3,000 and went home with my health.

Manning: It wasn’t in my wheelhouse either. They didn’t have any events where I could take advantage of running. Even in Assault, the game where they shoot tennis balls at you, the barriers were too small for me to hide behind. Watching on TV, you think, I can do that. Then you get out there and realize, This isn’t for me.

NOBODY WANTS TO SEE THAT S---

Ferraro: You know what’s funny: I was talking to a guy the other day and he says, “Gladiators was always such a good, clean show. . . .”

Nitro: I first tried ’roids in 1981. No one had heard of them then. I thought they must be safe because I was getting them from a doctor.

Ferraro: When Gladiators first started, I think that stuff was legal. And don’t forget: We had a show that was looking for the biggest, toughest guys. Some of those guys, most likely, were on steroids.

Nitro: A Rolls Royce pulls up to the Gladiators sound stage in season one. Lyle Alzado, the superstar Raiders defensive lineman, gets out. He was dating Lace. Later that night we go to his restaurant in Hollywood, Alzado’s. I ask Lyle about his steroid use and he gives me this long list of s--- he’s taking. I couldn’t believe what he was telling me—“Go big or go home.”

Sabre: I’ve never taken a steroid in my life. I don’t take amino acids or supplements either. When I was in the NFL [as a running back with the Rams, Raiders and Chargers], I worked out with the linemen. I didn’t care about size. I cared about being like Hercules.

Ferraro: We’re on tour, having a meeting. One of Goldwyn’s guys is there and he says, “On today’s agenda, we’re going to start testing for steroids.” That’s when you start seeing some of the guys drop weight. When they brought Gladiators back, in 2008, trust me, those guys were tested.

Dallas: Let me say something about that. They brought that show back and changed everything.

Ice: They ruined it.

Laser: They made it too Hollywood. They had Hulk Hogan hosting, which I thought was a joke. Our show, unlike pro wrestling, was real.

Dallas: They made the gladiators the villains and the challengers the heroes. Come on, man. Nobody wants to see that s---.

Laser: It pissed me off. They didn’t want to take direction from any of the ex-gladiators or even Johnny Ferraro.

Adamle: They didn’t want anybody who had anything to do with the previous show—directors, lighting people, camera people. The gladiators all of a sudden didn’t matter; they weren’t allowed to speak. They completely missed the point of the show—and that’s why it only lasted one year. We all raised a glass; it didn’t deserve to be on the air. So, yeah, we’re pissed off, collectively.

Ferraro: I can’t let the brand die. I’m developing an American Gladiators fitness chain. Hopefully some day we’ll do sports leagues. In the meantime, we’re working on a movie and developing another TV reboot with Mark Burnett’s production company. Understand: Networks don’t want to spend a lot of money.

Adamle: The original show died right before the birth of Netscape and the Internet. Imagine what it would’ve been like if Laser had his own blog, if American Gladiators had its own web site. It would’ve been off the charts.

Malibu: When you think of the ’90s, you think of American Gladiators. We were kinda the beginning of the reality shows.

Ice: We would’ve done that show for 20 years if we could have. We loved it. We had so much passion for it.

Laser: Years and years later, we have this bond—the kind of thing you only get through athletics, that connection where you get a different sense of self-worth and caring.

Dallas: I’ve never been around a group of people who cared about me like that.

Blaze: The last few years have been tough on the group. Siren [Shelly Beattie] committed suicide; Storm [Debbie Clark], who followed me on the Nebraska track and field team, fell into homelessness. Nitro had a heart attack in 2014; that really affected me. That’s my buddy.

Adamle: We lost Hawk [Lee Reherman] last summer [at 49, of unknown causes]. Most of us went to his funeral in Southern California, on the beach. That was sad. But we all stay in touch.

Ferraro: We’re inseparable. The gladiators, they’re basically my children. That show changed our lives.

Nitro: I unearthed the spandex the other day and put on my singlet—yes, it still fits after 20 years—as a gag for a workout I lead at my CrossFit gym. It felt better than it should have. Like home.