Matt 'Airistotle' Burns and the U.S. Air Guitar Championships Will Rock Your World

Take a look behind the curtain at the insane, high-octane, crazy train world of competitive air guitar exclusively on SI TV, with a free seven-day trial. Click here for more.

Matt Burns is playing the same 60-second song for the fifth time in a row. It’s a Saturday in early August, and we’re sitting in standstill traffic on the Brooklyn Queens Expressway. Outside, heat radiates from the pavement, thick and humid like a mosh pit. The car’s air conditioning offers a blessed reprieve from the stifling Staten Island apartment that Burns, 29, shares with Mike Katz, his best friend from high school.

Katz, who’s driving, slams his hands against the wheel. “Come ON,” he says to the Chevy truck in front of us. He’s trying to control his road rage because I’m in the backseat, but he also because hates being late—especially for something as important as the U.S. National Air Guitar Championships. Katz has to win in order to represent his country at the World Championships in Finland in a few weeks. The stakes tonight are lower for Burns. As the two-time defending world champion, he automatically qualifies for this year’s event.

The minute-long song Burns has on repeat is a mash-up that segues between the theme music of WWE superstar Undertaker, The Backstreet Boys’ “I Want It That Way” and “Right Now” by SR-71—classic songs from his adolescence. He strums a few fake chords. He doesn’t have to compete this evening, but he’s playing the halftime show in a few hours, and he’s using the performance to test the crowd’s reaction to a few moves he might break out in Finland. Burns firmly believes that a performance must have a beginning, a middle and an end, and it’s his job to perfect his act to be sure he takes the audience on that very quick trip.

“No one wants to see someone do this for more than 60 seconds,” Burns says, twisting around in his seat to look at me. “You could be the best ever and still—a minute is enough. It’s really hard to keep people’s attention for longer with literally nothing.”

Only four other people have won Worlds back-to-back since the competition started in 1996 in Finland. The idea was that if everyone in the world held an air guitar, they wouldn’t be able to hold a gun, and world peace would ensue. No one’s ever won three times, so Burns will be the best ever if he can win again next year.

Well, technically Airistotle will. Airistotle is Burns’ air guitar name, a character he describes as a 15-year-old kid who just got detention for the first time. Everyone who competes in air guitar assumes an alter ego; some of the all-time greats include Shreddie Mercury, Bjorn Turoque, Nordic Thunder, Windhammer, William Ocean, Hot Licks Hooligan... you get the idea. Burns is good friends with all of them.

We finally get to Williamsburg and head to a Duane Reade. Katz’s air guitar character, Brozone Layer, is a fratty tough guy, so Katz (who is not a fratty tough guy) wants to buy a bottle of Axe to spray in a celebratory cloud at the end of his performance. Burns needs to buy Croakies to secure his thick, black-rimmed glasses to his face; they keep flying off when he headbangs.

Burns is tall and lanky, still skinny in a teenage way, with thick dark hair and a smile that takes over his whole face. He peppers his speech with what sounds like ad-libs from a rap song. Excited Hell yeah!s and Let’s go!s bookend his sentences even when he’s hungover, which he is today. Over the past three days, he’s been partying with competitors who’ve flown to New York from all over the country for a chance to be America’s best air guitarist. The two beers he had at home before he got in the car helped. Hair of the dog and all that.

It’s sometimes hard to tell where Burns ends and Airistotle begins. But there’s no question as to who he is when he sees five of his fellow air guitarists—friends he’s known for as long as 10 years now—milling around outside the door.

“‘STOTLE!” yells Nordic Thunder.

“Hell yeah, dude!” Airistotle says, throwing up a shakka with his thumb and pinky extended from his clenched fist. He stands up straighter as he strides towards the group to give each person a hug. They greet him with admiration and a touch of reverence.

How did Burns, the son of a secretary and accountant from Staten Island, become the goofy king of playing an imaginary instrument?

It all started at a Best Buy.

Burns was in the store one day in 2008 when his friend spotted a DVD of the documentary Air Guitar Nation in a bargain bin. The movie chronicles the first season of U.S. Air Guitar, the league that Kriston Rucker and Cedric Devitt founded in 2003. After going to Finland for Worlds, they couldn’t believe that America wasn’t represented, so they started the country’s first competitions in New York City and Los Angeles. Fifteen years later, regionals take place in 25 cities across the country. Winners go to regional semi-finals, and then head to Nationals, which is held in different city each year.

As soon as Burns saw the film, he was hooked.

“I thought, this is the stupidest, dumbest, most gorgeous, beautiful, amazing thing I’ve ever seen in my entire life,” he says. “I was like, sign me up. I was immediately drawn to air guitar for so many reasons. The best way I’ve ever heard it described is that it’s one-third comedy show, one-third concert and one-third sporting event wrapped up into this one thing. It’s like a drag show, but for frat bros.”

Burns has always loved performing. He was on his high school’s improv team and the easiest way he could hang out with girls was to act in the plays put on in collaboration with the sister school of his all-boys, Catholic high school. At 19, he was too young to get into the bars where the air guitar competitions took place, but that didn’t stop him; he drove down to Philadelphia and snuck into a bar when the bouncers changed shifts. He hid in the bathroom for three hours until the place got crowded enough that no one would notice he hadn’t shown his ID. Word spread in the air guitar world that a kid was sneaking into bars not to drink, but to shred oxygen for 60 seconds.

Burns first made it to Nationals in 2010, and took home his first title in 2012. Competitions are judged using the old school figure skating scoring system, on a scale of 4.0 to 6.0. Air guitarists are evaluated on technical merit (whether it looks like they’re playing notes you’re hearing in song or not), stage presence (costume, character, levels of crowd involvement), and “airness.”

“By far most the most important and borderline impossible to define is airness,” Burns— or maybe Airistotle, in this case—says. “It’s the it factor, the je ne sais quois. The best way I’ve heard it described is that it transcends the act of imitation and becomes an art form in and of itself. So this dude on stage isn’t pretending to play the guitar anymore, he’s playing the air guitar, and he’s in the zone. He’s feelin’ it. And he’s shredding licks way beyond his capabilities. He looks like he’s having more fun on stage than anyone’s ever had in their life.”

Burns won the Worlds in 2016 and 2017. Sometimes he performs at corporate events, and he recently acted in a play his friend wrote and directed about air guitar called Airness. He went to college for a few semesters at the College of Staten Island but dropped out “because Die Hard was on TV. And then Die Hard 3 was on, and what was I supposed to do?” These days he bartends at the Phunky Elephant, a gastropub a few minutes away from his apartment, but mostly he just practices his moves with Katz and the friends they grew up with. They cut together his 60-second song edits, help him work out his choreography and go to Zumba classes to hone their dance skills.

“Airistotle hasn’t just won, he’s become our Air Jordan,” says Rucker, one of the founders. “Seeing him pull that off has been like watching a slow-motion hurricane that actually improves the aesthetics of the coastline. And when I talk to him these days, I’m struck that he’s added a mental dimension to his craft that—combined with his physical gifts—is almost unfair. Listen to him break down the elements of performance: character coherence, 60-second story arc, the power of entrance, how to prepare for a curveball compulsory track, how to rope-a-dope the crowd with faux vulnerability, et cetera.”

It’s true—Burns is eloquent when describing the technique and gamesmanship that goes into planning. He’s also just as happy talking about how much he loves this community. The theatrics drew Burns to the sport, but the people are why he’s continued to come back. Why he hopes he keeps doing this forever.

Before Nationals, all the contestants gather in the green room. They’re drinking beers, hugging, putting face paint on each other. Nordic Thunder—who isn’t competing this year but who’s nonetheless wearing his Viking costume—walks in with a hat filled with numbers written on pieces of paper to determine the order of performances. It’s a bit of a crap shoot; you don’t want to go too early because the crowd won’t be warmed up and the judges are usually tougher, but you don’t want to go last because others will have used many of the good moves already.

Before everyone picks out of the hat, Nordic Thunder gives a speech. Burns is standing in the doorway watching the competitors, one of whom will join him at Worlds in Finland when tonight is all over.

“This has been a huge part of my life since 2006,” Nordic Thunder says. “It’s been a place I felt I could be comfortable in my own skin, and I don’t get to feel that in my everyday life. And I feel that way around you f---in’ weirdos.”

Burns claps, nodding as hard as he headbangs, his glasses secured to his head.

“Let’s go!” he yells.

Dad Bod Jovi performs first and isn’t great. He doesn’t possess that “je ne sais quois.” Kit Kat goes next, and she’s better—she wears a rainbow, feathered collar with sequins and gets low to the stage as she spins her arm around for the power chords. Then Virgin Airy takes the stage; she’s going to have her third child in two months, and let me tell you, you don’t know badass until you see a woman who’s 32 weeks pregnant absolutely shred the air guitar. She twists her wrists, flips her hair around, thrusts her hips and belly, and slides her hand up and down the imaginary neck of her imaginary instrument. This year’s Nationals’ field is wide open, because last year’s winner, Mom Jeans Jeanie, gave birth to her second kid 10 days ago.

Brozone Layer (Burns’ roommate Katz) rocks out, but his scores aren’t very high. The five judges—comedians and former competitors—dock him for spraying Axe everywhere and “making the place smell like an Uber.” Burns, who’s standing next to me in the balcony, shakes his head; it looks like Katz won’t be going to Finland with him.

But Burns gets excited again when Windhammer takes the stage. Windhammer is completely bald with a bushy red beard. He’s shirtless, wearing only a pair of leather chaps, and hasn’t smiled once in character in the 10 years he’s been doing this. Burns and Rob Weychert (Windhammer’s real name) love each other, but Windhammer and Airistotle are sworn enemies.

Windhammer tears it up to an intense metal song I haven’t heard before, his movements precise and exact.

“That was like listening to the entire Metallica catalog on a mound of f---ing cocaine,” Burns says, shaking his head.

Then he darts away; round one is over and it’s time for the halftime show. The five competitors with the highest scores from the first round will move onto the second. While they all prepared and practiced a song for their initial performance, for round two, they’re surprised with a song and will have to improvise.

The lights go down briefly, and when they come up, Airistotle’s light blue flat-brim hat is sitting on a stool on stage. It bears the image of Rocko, the main character from the cartoon Rocko’s Modern Life, a Nickelodeon show from Burns’ childhood. The somber church bells of Undertaker’s music play, which I heard in the car about 30 times. Now that I’ve seen a competition, the comparison between WWE and air guitar makes much more sense: the heels, the faces, the make-believe, the (yes, seriously) athleticism.

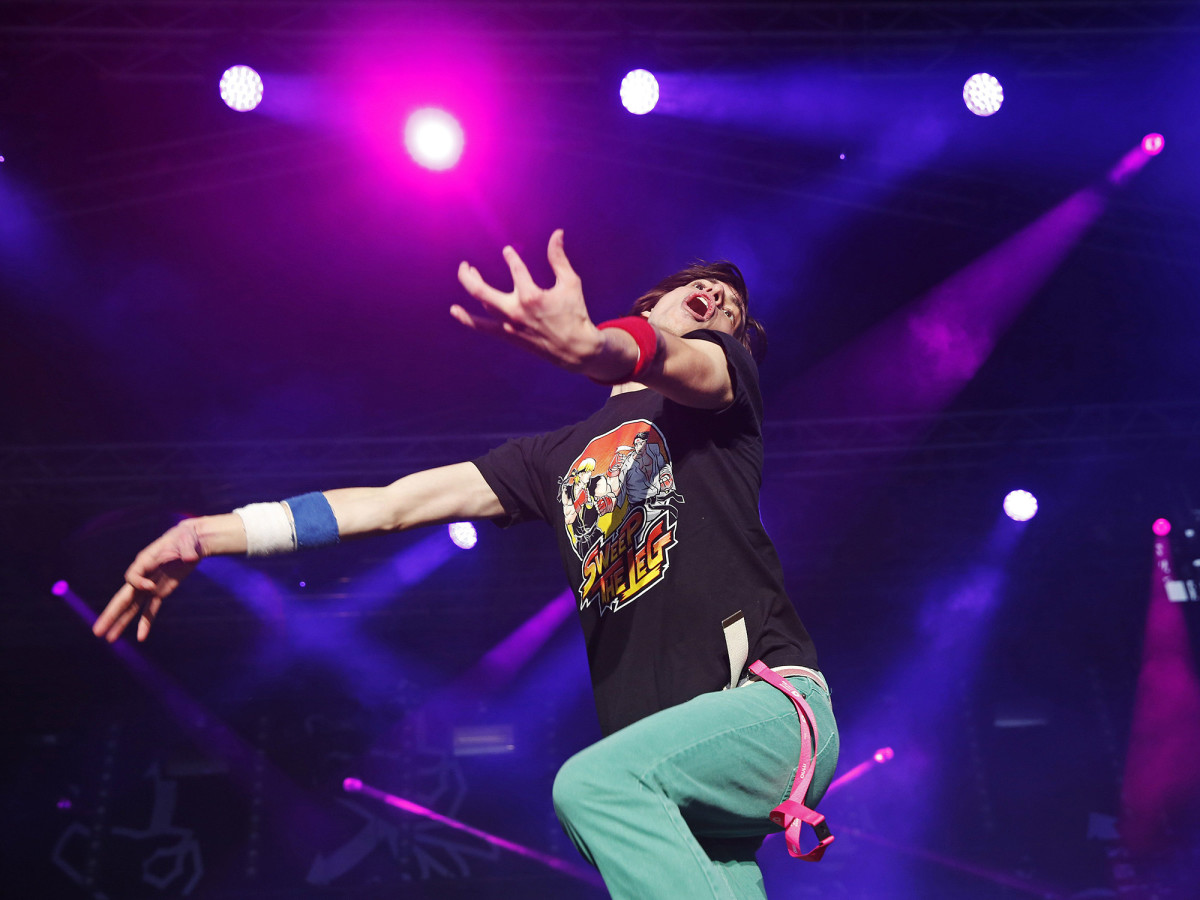

As the soaring chords of The Backstreet Boys take over, Airistotle himself appears and puts the hat on his head. The crowd goes nuts as the riff of “Right Now” begins and Airistotle starts plucking the notes from the empty space around him. He moves with frenetic-yet-controlled, chaotic-yet-choreographed energy, hopping from one side of the stage to the other. His expressions of surprise and joy are as timed to the music as the movements of his arms and legs. I finally comprehend what he meant when he told me earlier that great air guitar transcends the act of pretending to play an instrument and becomes something entirely its own. Compared to Airistotle, everyone I’ve seen so far tonight is an amateur.

But you will not understand this until you see it live. There’s just no way. I’m doing my best to describe it, and you can watch videos, but until you witness this in person you will not feel the airness. By the time the last chord hits, and Airistotle stands with his back to the audience, hand raised to the sky, breathing heavy, the crowd is the loudest it’s been all night.

I find Burns sitting on a couch in the green room after his performance. For the first time since I’ve met him, he can’t speak. He just shakes his head. Finally he says, “I’m still coming down. Give me a minute.”

A woman who goes by Georgia Lunch wins the competition. She’ll be going to Finland with Airistotle. At the end of every air guitar show, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Free Bird” plays, and the crowd is invited to come up on stage to shred with the competitors. Everyone is embracing, singing, “Lord knows, I can't change.”

Airistotle is in the middle of the crowd, holding a Bud Light, his arms around two of his friends as they sway back and forth. Earlier today, as he showed off the various air guitar trophies in his Staten Island living room, Burns turned to me.

“I’m just so happy when people still take make-believe this seriously as adults,” he said. “People lose the ability to not care what people think and just have as much fun as they can. And these people are the all-stars of that.”

This many people air guitaring at once is one of the most freeing things I’ve ever witnessed. I join in, shaking my head back and forth, windmilling my arm around, miming the fast parts of the song on my hip. When you let yourself get into it, it’s euphoric. If you’re not a gifted dancer, you have something to do with your hands; this is performing for people who can’t sing, play an instrument, or dance, but who want to be rockstars for 60 seconds. It’s a high.

The last time Burns was at the World Championships, a bunch of the air guitarists went out for karaoke. Someone chose to sing Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody.” At the end of the song, one person who’d never been to a competition before said to Burns, “I never thought about ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ that way.”

“And I was like, ‘What do you mean?’” Burns says. “And they were like, ‘You know at the end of the song when he sings nothing really matters?’ And I was like yeah. And they were like, ‘No nothing—’and they held up their air guitar—‘It really matters.’

Burns stands on stage drunk, singing, sweaty, surrounded by the people who accept him, who admire him, who understand that he’s mastered an art very few even know exist. Who will continue to love him regardless of whether he makes history at Worlds in a few weeks. Who see him as an adult when the rest of the world would say he’s never grown up.

And in this moment, nothing has never mattered more.