SKOL Searching: The Vikings' floundering rush attack and its effect on the rest of the offense

Since the Minnesota Vikings drafted Adrian Peterson in 2007, the offensive identity in the Twin Cities has almost exclusively revolved around the run game. After Peterson’s departure, Dalvin Cook quickly followed in his footsteps, and Mike Zimmer’s love of the run game kept the identity thriving.

With Zimmer now gone, Cook climbing in age and the emergence of Justin Jefferson, that identity has finally been challenged this season.

The Week 14 loss to the Lions might have officially buried it.

The Vikings managed just 22 yards on 17 attempts, an average of 1.3 yards per rush. The longest run of the game was a five-yard gain by Dalvin Cook. Minnesota managed a 12% success rate on those runs, meaning only two runs had positive expected points added (EPA).

“They made more plays than us. I thought they played with more energy than us at times,” Cook said. “... We just have to regroup and be us this week. We just have to get back to the ground and do what we do.”

But Week 14 was not an outlier. Since the Vikings’ Week 7 bye, Minnesota has the lowest rushing success rate in the NFL, 31.4%. Since Week 11, it’s 22.4%.

For the season, the team ranks 27th in rushing yards per game, 22nd in yards per carry, 24th in rush EPA/play and 21st in rush DVOA.

It is unclear whether Cook, the offensive line or the scheme should shoulder the most blame, but they have all played a part.

The offensive line's performance has received mixed reviews this season. The unit ranks 20th in ESPN’s run-block win rate statistic but is the 4th-best run-blocking team, per PFF grading.

Per The Athletic’s Alec Lewis, 33.9% of the Vikings’ runs since Week 10 have gone for zero or negative yards, most in the NFL. Lewis also noted Minnesota ranks 31st in yards before contact in the last five weeks.

That points towards a struggling offensive line, but it appears Cook isn’t getting the most out of his opportunities either.

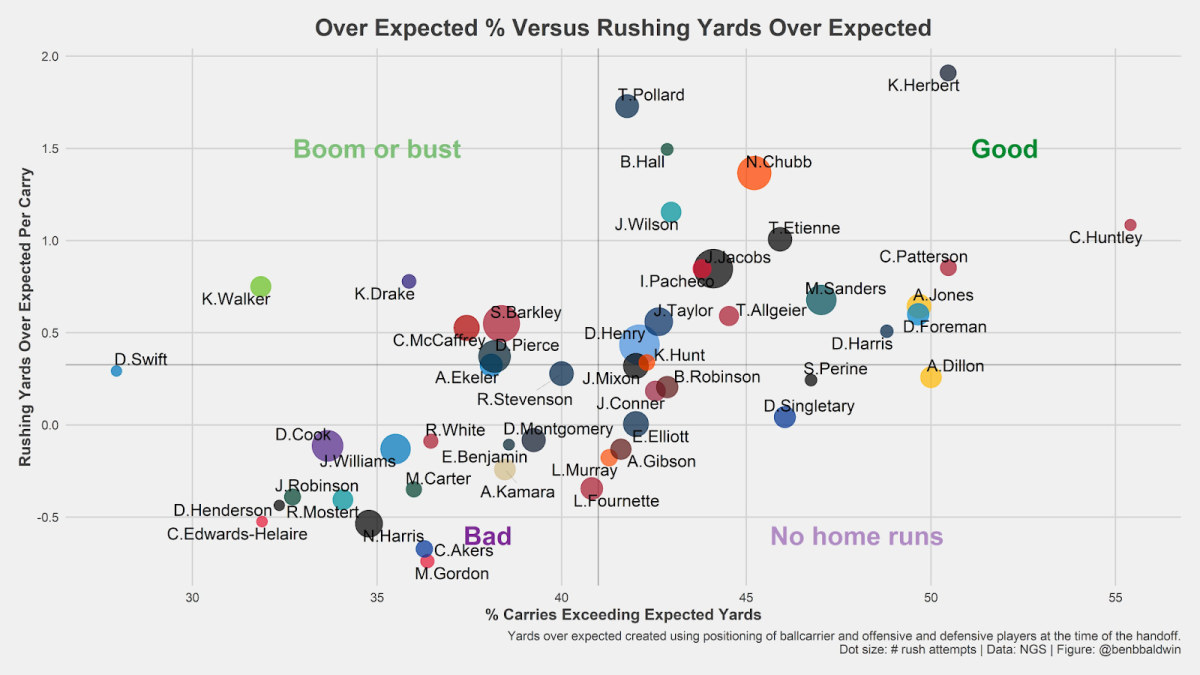

Cook ranks 30th in the NFL in rushing yards over expectation among running backs. Here’s a chart from Ben Baldwin that illustrates some of the issues.

The chart shows that Cook exceeds expectations on less than 35% of his carries and on average is not quite reaching the expected yardage. That’s a departure from previous seasons. In each of the last three years, Cook had averaged more yards per carry than expected.

The result, regardless of the source, is a floundering rushing attack. The question now is whether a successful run game can emerge this season and the extent to which it could affect the rest of the offense.

The former may depend on the health of the offensive line. Left tackle Christian Darrisaw and center Garrett Bradbury are expected to return against the Colts on Saturday. When the unit has been fully healthy, it has been a solid run-blocking team.

When Darrisaw specifically is on the field, the Vikings are averaging 4.76 yards per rush. When he’s been sidelined, Minnesota is averaging 2.88 yards per game. That’s reason enough to believe there could be improvement coming and that O’Connell will continue to give it an opportunity.

But even if it doesn’t, are other parts of the offense in jeopardy? The conventional fear is without a semblance of a running game, play-action can’t and won’t be effective.

In theory, it makes sense. If a running game requires respect from a defense, either for its consistency or explosiveness, that would understandably cause linebackers and safeties to pay greater attention and open up holes in the passing game. Kirk Cousins said as much on Tuesday.

“I do think that efficiency running the football makes everything a lot easier,” Cousins said. “So, you can do it other ways, but I think always the preferred way is to be able to start by running the football effectively.”

Cousins acknowledged that’s not always going to happen – like last week against the Lions – and said the team has to find ways to win despite that, but that “on a larger sample size scale” they want to be a team “that can really lean on the run game.”

That might be the overall offensive philosophy, but it’s not needed to run an effective play-action offense.

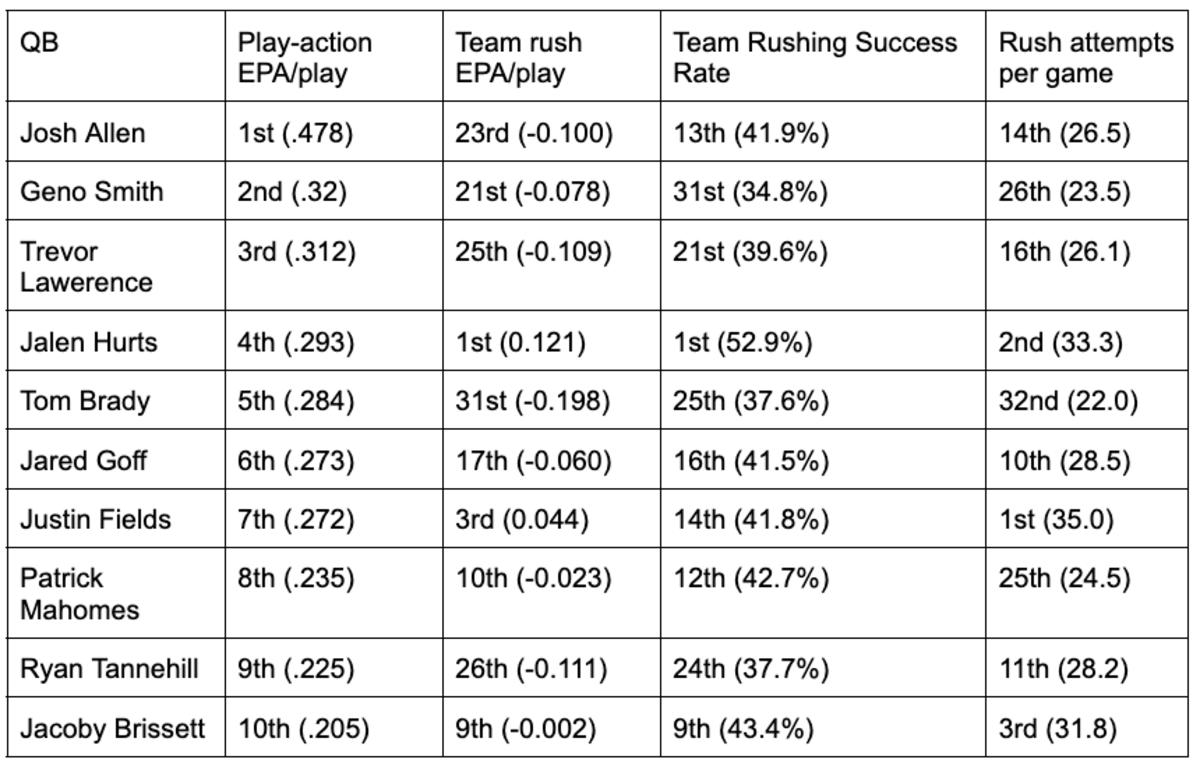

Josh Allen leads NFL QBs in play-action EPA/play, but the Buffalo Bills rank 23rd in rush EPA/play and 13th in rushing success rate. Turns out, that’s more of a norm than an anomaly.

Let’s look at the top-10 QBs in play-action EPA/play and how that compares to rush EPA/play, rushing success rate and rush attempts per game.

Only four teams – the Eagles, Bears, Browns and Chiefs – that have top-10 QBs in play-action EPA/play also have top-10 running games in either EPA/play or rushing success rate. The rest deploy rather ineffective running games despite their prowess in play-action.

Cousins hasn’t had the same success throughout the full season, he ranks 27th in play-action EPA/play this year, but did well in those situations on Sunday. On eight play-action dropbacks, he completed 6-of-7 passes for 125 yards and had an average depth of target of 17.10. He had an 88.6 PFF grade on those plays. He also took one sack.

It also tracks historically for Cousins, who has been a solid play-action passing quarterback despite bad rushing attacks. Last season he ranked 10th in play-action EPA/play even with the Vikings in the bottom third of rush EPA/play and success rate.

That provides at least some evidence Cousins can improve in that area the rest of the season and be successful in play-action opportunities even with a depleted run game.

It’s become a prerequisite for Minnesota during this running slump and something head coach Kevin O’Connell said is a requirement for modern offenses.

“Sometimes it has to. When we’re not getting as much out of the run game as maybe we prepare for or hope, those opportunities can still come. The threat of a run game, depending on the down and distance, depending on the formation, the presentation that you give,” he said.

That tracks with the data. Showing the possibility of the run, even if the team has struggled to run the ball up to that point, can still create the desired effects. The Seahawks run the ball at one of the lowest rates in the league and are one of the least-effective teams in doing so, yet Geno Smith still generates the second-most EPA/play on play-action. Just the sheer possibility of a run, even if it likely won’t lead to a positive result, is enough for defenses to bite.

It’s possible O’Connell could follow suit, lean into a pass-heavier offense and expect teams will continue to bite on play action. That’s not likely though. For starters, the Vikings are already one of the pass-heaviest teams in the league. The Vikings rank 28th in the NFL in rush attempts per game (23.3) through 14 weeks, so there’s not much to cut out.

O’Connell has also repeatedly stated throughout the season that he wants to get the run going and has stuck with it in recent weeks despite the struggles. That’s not unusual for coaches across the NFL. As the chart showed, while many of the teams in the top 10 of play-action EPA/play aren’t running the ball effectively, many run the ball at or above league-average rates.

Coaches appear to feel they need to show they are willing to run even if it’s not effective. O’Connell has displayed that throughout the season, frequently trying to establish the run on early downs in the early going of games. But when the Vikings get late into a game or late into a set of downs, O’Connell reverts to passing.

Against the Lions, 16 of Minnesota’s runs came on first or second down. The only other run was Cook’s failed fourth-down run in the first quarter. Against the Jets, just two of the team’s 25 runs were on third or fourth down.

While revitalizing the running game is a priority for the Vikings, they will continue to throw more often than not, particularly on late downs. That’s this team’s identity – and it’s not going anywhere.