Fantasy Draft Strategy: What to Do When There’s a Wide Receiver Run

The guy with the third pick in your fantasy draft has carefully built his team: Christian McCaffrey in the first round, Tony Pollard in the second, Tee Higgins in the third, Joe Burrow in the fourth and Diontae Johnson in the fifth. Ideally, he plans on securing wide receiver depth in the sixth and seventh rounds but – as his pick approaches – a wide receiver run occurs and the players he wants are gone.

Receiver-happy drafters on Underdog snag Jordan Addison, Gabe Davis, Jahan Dotson and George Pickens ahead of their average draft positions (ADP). The 1.03 drafter faces a predicament: Should he draft a running back like J.K. Dobbins or Miles Sanders at a discount despite having two solid RBs, or should he reach and draft a WR like Quentin Johnston or Treylon Burks at a premium to ensure having a strong third and fourth WR?

Fantasy Data Pros ran its first annual Best Ball Data Bowl—a competition geared toward analyzing data from Underdog’s 0.5 PPR Best Ball Mania (BBM) 3 tournament—and my submission focused on that exact dilemma. How does a run at wide receiver affect the draft board, and what should drafters do in BBM4 when a run occurs?

Let’s dive into the data.

What is a wide receiver run and how do we quantify it?

The first step in determining which strategies work best during a wide receiver run—whether to take a WR at a premium to avoid getting buried at the position or take an RB, QB or TE at a discount—is defining what a wide receiver run is. Underdog releases pick-by-pick data for its BBM1, BBM2 and BBM3 contests. The data contains information on every player drafted, what pick they were drafted, what their ADP was at the time they were drafted, and more.

I created a metric called “wide receiver over expectation,” which tracks the difference between the total WRs taken at a given pick in the draft and how many WRs were expected to be taken at that point. Take into consideration the 1.03 drafter. According to Underdog’s current ADP, he should have expected 35 WRs to go off the board by the time he picked at No. 70. However, in that example, receivers were pushed up and 39 WRs actually went off the board. Four WRs were drafted above expectation.

The wide receiver over expectation metric essentially tracks how WR-heavy a draft room is, and the metric is scaled to make it comparable across every pick in a draft. From there, a wide receiver run can be defined in various ways. It should, however, match what a wide receiver run feels like during a draft. For my analysis, I defined a wide receiver run as:

- An area of the draft of at least eight consecutive picks where the amount of wide receivers taken above expectation is at least one standard deviation above the mean.

- Within that stretch of picks, the number of wide receivers taken is greater than half of the total players taken. (For example, a run of eight picks would include at least five wide receivers taken in that range.)

In other words, a wide receiver run is a stretch of at least eight picks where many more wide receivers are taken than expected. Wide receiver runs are then labeled as such in the data, allowing for analysis on picks occurring during a run.

How does a wide receiver run affect draft boards?

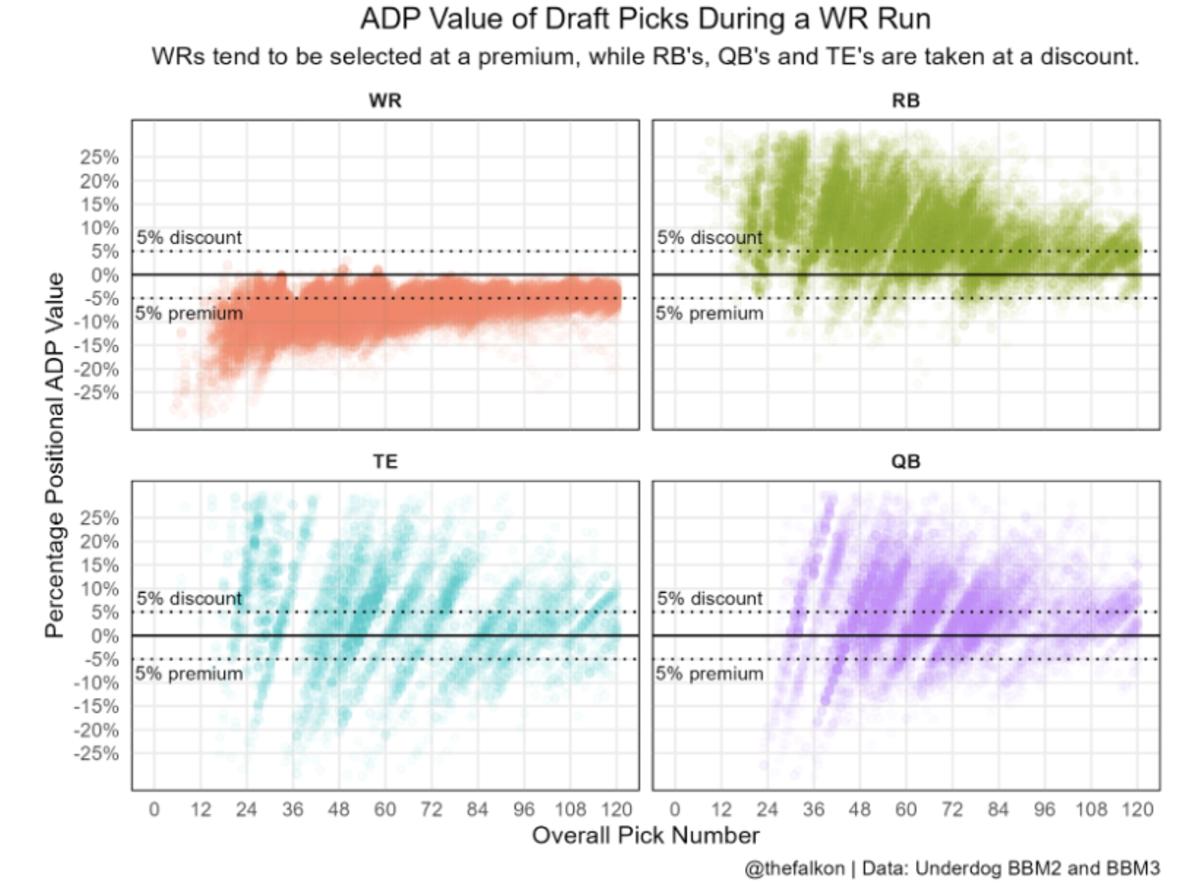

Before diving into the best strategy for tackling a wide receiver run, let’s first look at what happens to ADPs when there is an active wide receiver run:

The graph plots every draft pick in relation to the percentage positional ADP value of the pick. Rather than grabbing a player’s individual ADP, positional ADP grabs what the position’s ADP was. (In other words: If James Cook was selected as the RB31, positional ADP grabs what the RB31’s ADP was rather than James Cook’s individual ADP.) Then, percentage positional ADP value is the difference between where the player was drafted and his position’s ADP, divided by his position’s ADP.

During a wide receiver run, receivers are rarely available at their positional ADP and are frequently taken at a 5% or more inflated cost. Conversely, running backs are often 5% cheaper or more, and quarterbacks and tight ends aren’t too far behind. This tells us that wide receivers are pushed up during a run, and other positions become much cheaper.

ADPs begin stabilizing about a round after a run has ended and approach baseline levels around two rounds after.

What should you do when a wide receiver run is happening?

It’s one thing to know how a draft board changes when there is a wide receiver run, but the harder part is knowing what to do. A drafter can use two main strategies: They can a) participate in the run themselves and take a wide receiver to avoid getting shut out of the position; or b) choose not to participate and take advantage by drafting another position at a discount.

Which strategy is better?

In terms of how many points a best ball team scores during the regular season and a team’s likelihood of advancing to the playoffs, the data is fickle.

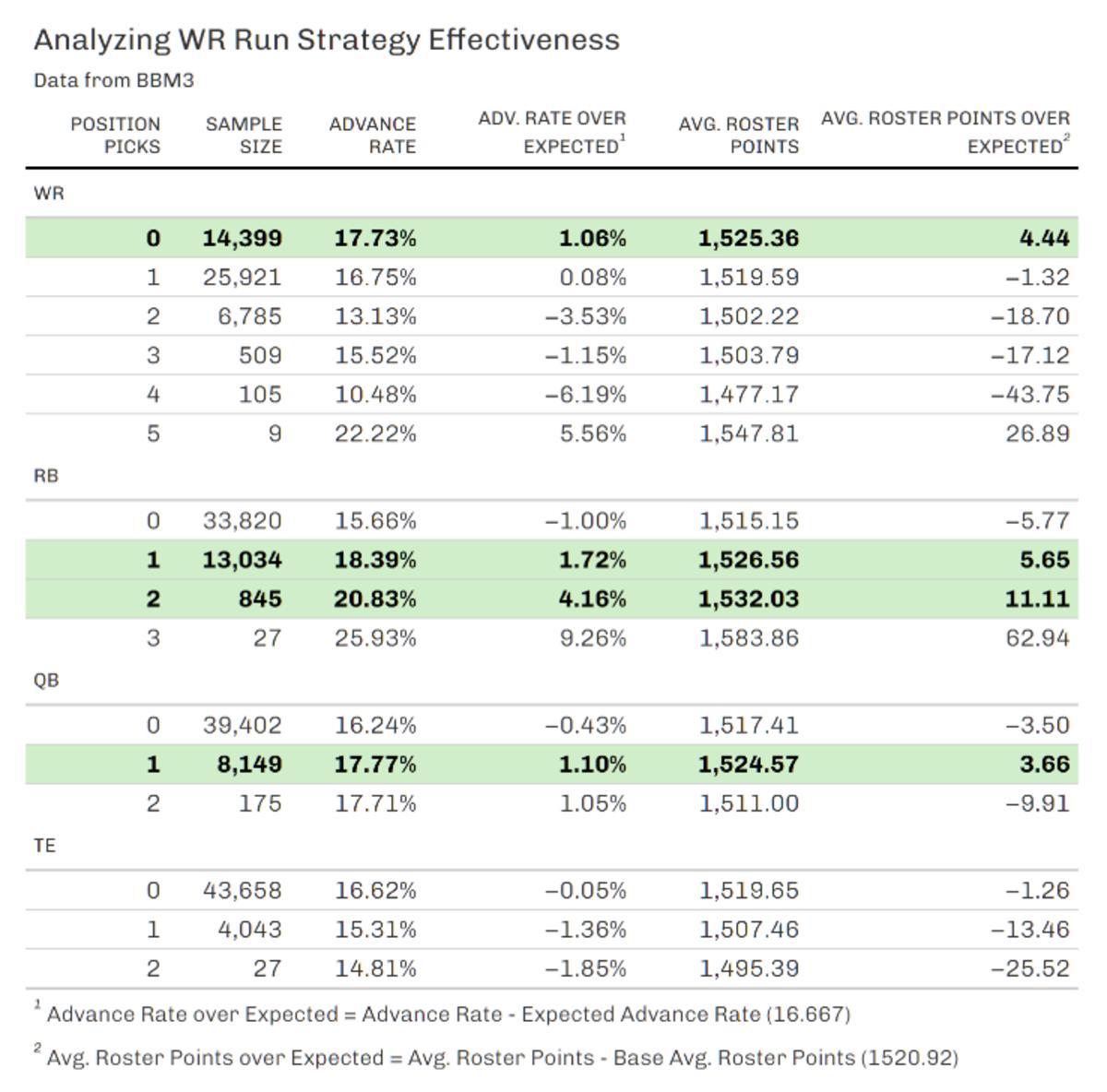

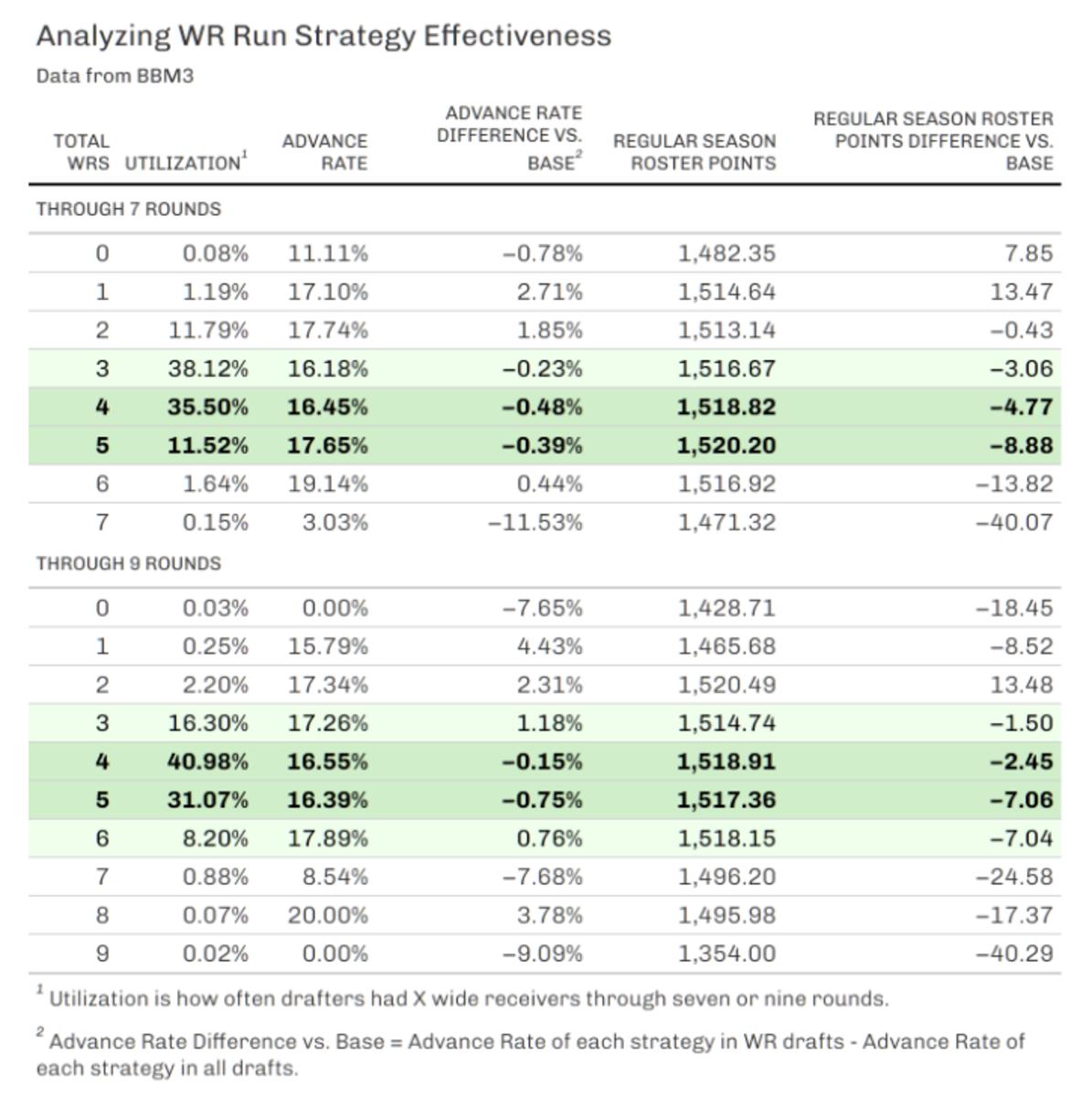

First, let’s take a look at how drafters fared in BBM3 depending on how many WRs, RBs, QBs or TEs they took during a run:

At first glance, selecting a RB or QB during a WR run looks optimal in BBM3, yielding a 1% or greater boost to advance rate and about a 3-11 point boost to how many points a team scored during the regular season.

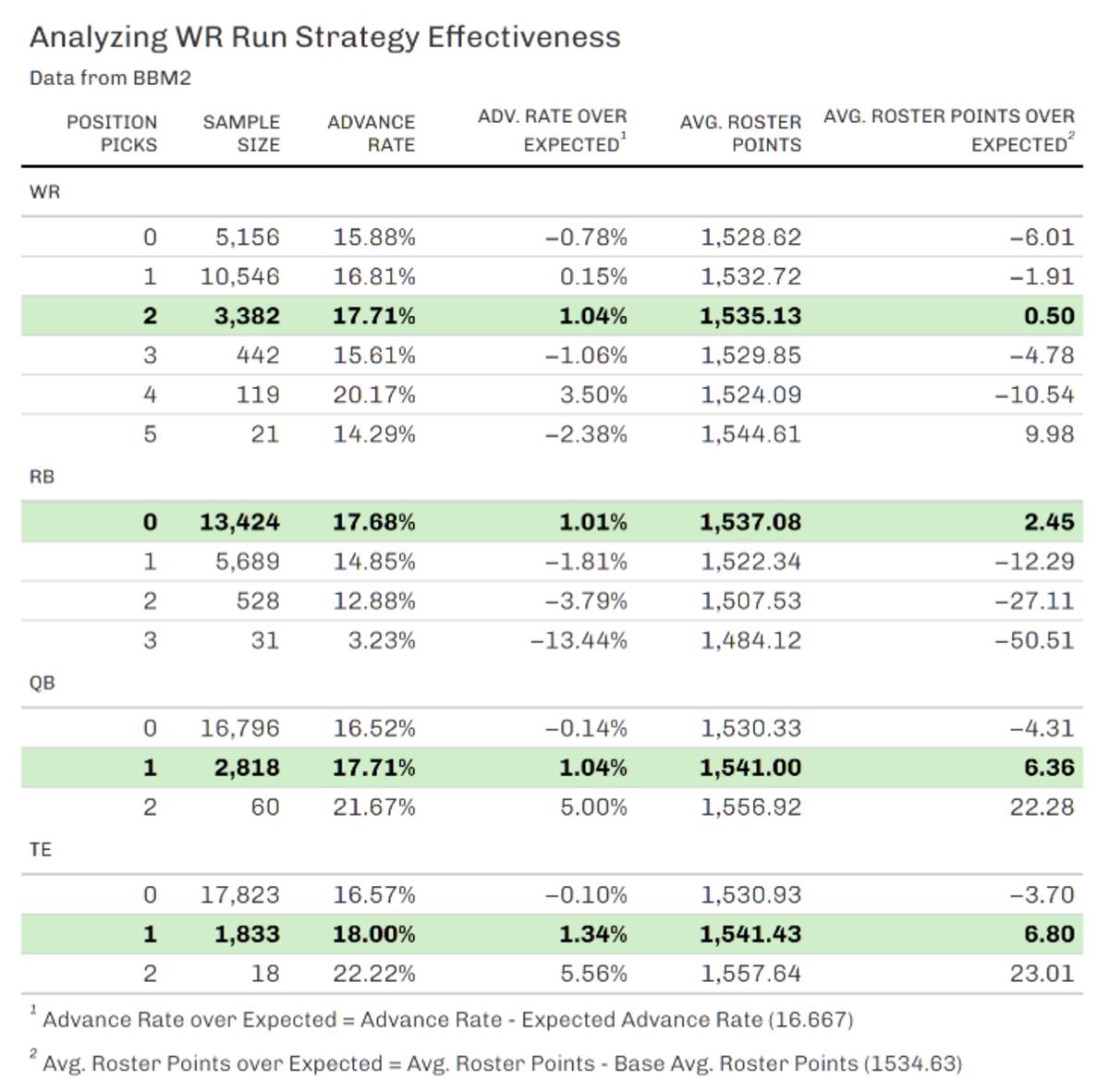

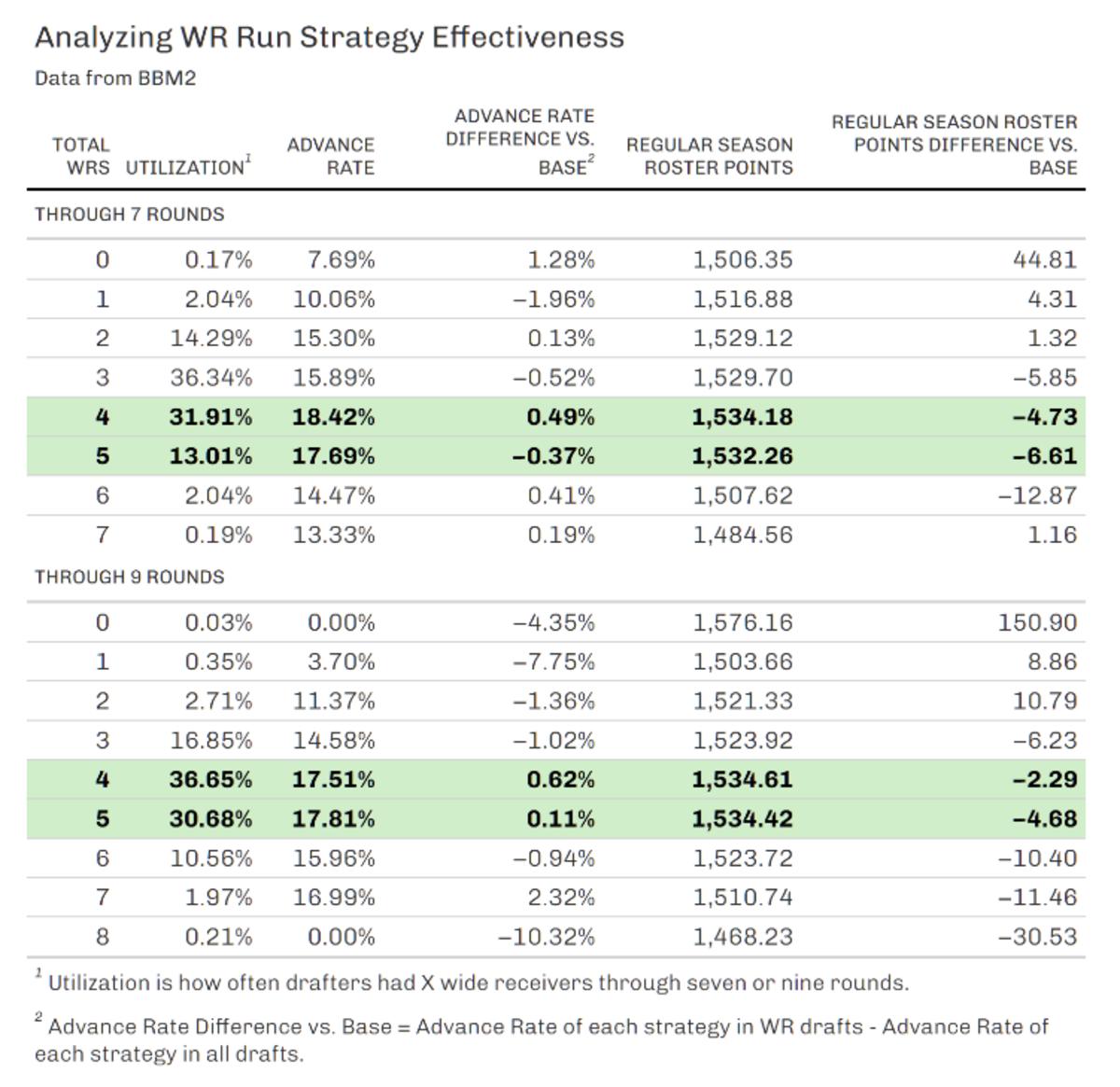

Let’s see if that was the case in BBM2.

Nearly the opposite was true: Selecting WRs during a WR run was necessary to get to base advance rates, and taking more than one yielded a 1% boost to advance rates. At the same time, drafting a RB during a WR run decreased a team’s advance rate by about 1.8% and reduced a team’s end-of-year points by about 12 on average. Alternatively, drafters who opted to take a QB or a TE received similar benefits to drafters who took WRs.

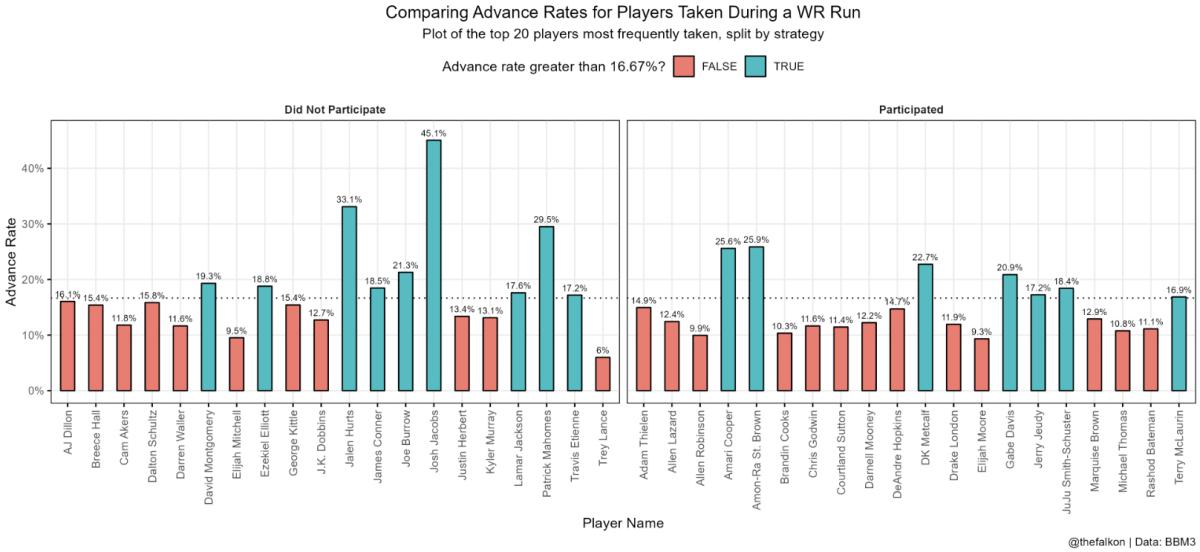

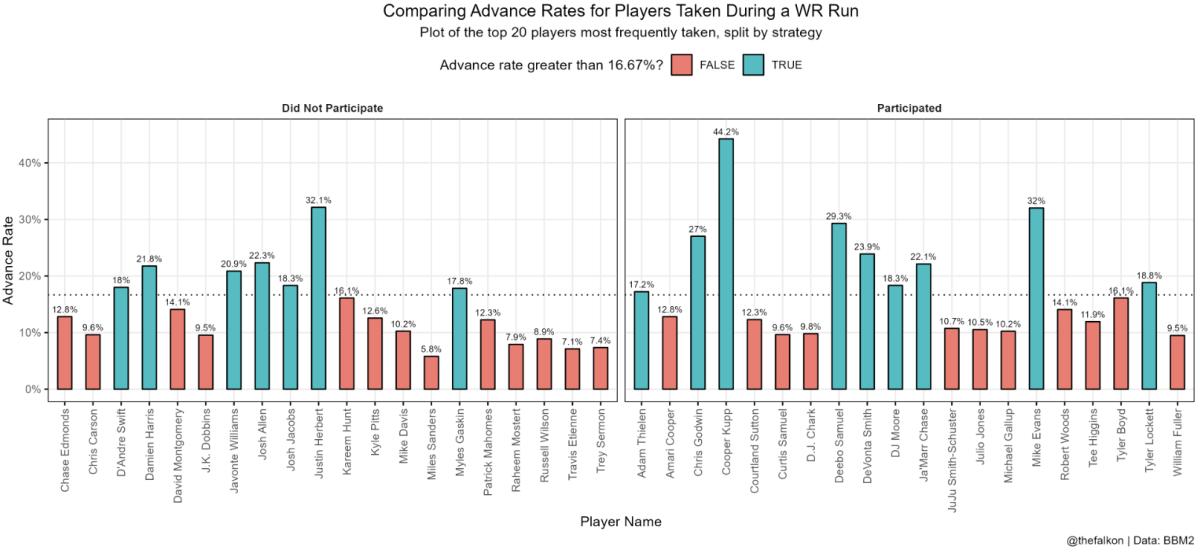

The results make more sense when we dig into which players were selected during a wide receiver run. The following two graphs plot out the top 20 most frequently selected players for drafters who participated in a run by taking a WR or did not participate in a run by taking another position.

The reason why taking a detour and selecting a RB or QB was optimal in 2022 is simple: Players like Jalen Hurts, Josh Jacobs and Patrick Mahomes provided meteoric advance rates, and other players were, by and large, not backbreaking picks. On the other hand, many wide receivers underperformed their ADP, and when WRs like Amari Cooper, Amon-Ra St. Brown and DK Metcalf did hit, it wasn’t to the same extent as the previous group.

BBM2 shows the opposite effect. Receivers like Cooper Kupp, Deebo Samuel and Ja’Marr Chase were incredible hits, while running backs like Raheem Mostert, Travis Etienne and Mike Davis were landmines.

The effectiveness of each choice–whether to go with the run or step to the side and take a detour–was heavily influenced by who the best players were that season.

The next set of strategies for best ball drafters to consider is structural. Previous research has shown that drafting 4-5 wide receivers by Round 7 and 4-6 wide receivers by Round 10 is optimal in Underdog BBM drafts. Additionally, Pat Kerrane has shown how most wide receiver spike weeks come within the first nine rounds.

Instead of looking at individual picks, we can use the wide receiver over expectation metric to sort each draft room on how WR heavy it was. From there, we can grab the top 5% most WR heavy draft rooms in BBM2 and BBM3 and see how tried and true wide receiver strategies fare in those rooms.

While drafting either four or five WRs by Round 7 and Round 9 underperformed how a team scored during the regular season, both strategies appear to remain optimal in WR-heavy rooms. Notably, drafting more WRs and drafting them earlier seemed optimal for regular season scoring in BBM3, but that held less firmly in WR-heavy rooms. Keep in mind, however, that these conclusions are drawn from a small sample size (5% of BBM3 drafts and 5% of BBM2 drafts) and may need more data to support them in the future.

Conclusions

Before diving into takeaways, it’s worth noting that regular season scoring and advance rates shouldn’t be the only lens to quantify whether a particular strategy was effective or ineffective. Two-thirds (or $10 million) of BBM4’s prize pool is dedicated to playoff prizes, and 20% ($3 million) of the total prize pool is awarded to finishing first. Constructing teams to have the requisite weekly upside to take down an uncorrelated three-week tournament is as important–if not more–than advancing out of a 12-person pod. Research on how inflated WR ADPs impact a team’s weekly upside is an important next step.

This article’s data offers no definitive answer on the best approach to handling WR runs. BBM2 and BBM3 illustrated that different approaches can work. When there’s a WR run, and the WRs in that range hit, it’s still important to draft a WR. Other times, when there’s a WR run, and the WRs in that range are weak and different positions are stronger, it’s important to draft those positions at a value.

Constructing teams well–drafting four or five WRs by Round 7 and 9–still matters. It’s easy to say play the best players and move on, but each drafter should assess different positional tiers and evaluate whether one position still provides an edge over another. There was no sense in grabbing a falling Mike Davis in 2021 if the opportunity cost is a WR with more upside.

The data may offer clues, though, and BBM3 provides a word of caution about only grabbing WRs when they are flying off the board. The ADP landscape has changed in BBM4, with more wide receivers drafted earlier than ever. By just how much has the landscape changed? We can see.

It’s an imperfect exercise, but we can take BBM4’s current ADP, treat it as if a draft strictly followed ADP, and then join it with the closing ADP from BBM3. We can apply the same methodology from before to gauge how WR-heavy BBM4 is. The result: BBM4’s current ADP through 10 rounds would be the sixth heaviest WR room in all of BBM3.

Think back to the 1.03 drafter. Running back prices are historically deflated, and those cheaper RBs sometimes project better than the WRs available around them. It might hurt to have one less wide receiver, but a running back drafted at a discount (think J.K. Dobbins, Dameon Pierce or Isiah Pacheco) might furnish a team with comparable upside and project better throughout the season. And yet, it’s also more important than ever for them to secure the requisite firepower at wide receiver before it gets too late in the draft—Round 9, sometimes!—and there’s nothing but low-ceiling receivers left. High upside RBs can still be found soon after the WR well dries up.

So, does the Underdog drafter continue to pay up for WRs or do they take advantage of discounted RB prices? That dilemma has been central to conversations about building tournament-winning teams in BBM4, and it is largely unsolved.

In regards to withstanding a WR run or advancing out of WR-heavy rooms, the data doesn’t say one approach is better. Theory will only take you so far. Draft wisely.