Through the Fire and Flames

Romain Grosjean could not break free. His foot was lodged underneath his gas pedal. Something firm was trapping him from above. And it was getting warm. At first, he wasn’t sure what had happened. He opened his eyes and tried to escape. Maybe I’m upside down, he thought. Maybe I’m pinned against the wall.

Someone would come rescue him soon. They always did. He looked right, then left. Orange. Is that the sunset? No, the sun hasn’t been up for hours. Lights from the circuit? No, this was brighter, and hotter: fire.

He started asking himself questions about where he’d feel the burn first and how painful it would be. Those who’ve watched the never-released rear-facing camera recording from Grosjean’s car recount first seeing a man with fear in his eyes, then one resigned to his fate. He knew he was going to die.

Formula one is an unfair sport. Perhaps the most unfair sport. Unlike most of the major American leagues, which have guard rails like the draft or a salary cap to ensure parity, F1 is happy to let teams spend their ways to competitive advantages. Top teams like Mercedes and Red Bull don’t just have the best drivers, but also the money and resources to build cars that lead the pack year after year; their more powerful engines and more aerodynamic chassis have propelled them to every championship since 2010.

A financial gap tipping the playing field isn’t novel. Moneyball changed baseball and gave lower-budget teams a path forward; an 18th-round reliever, in the right circumstances, might be more valuable than an expensive arm. But there is no amount of coaching that can fix a bad car. A great driver can make up fractions of a second per lap around a track, but skill is worth only so much.

In 2019, Mercedes, now on the hunt for its eighth-consecutive world championship behind leading man Lewis Hamilton, spent $442 million perfecting their cars. Meanwhile, Haas, Grosjean’s team for five years, zipped around the same tracks with a budget less than half that amount. As things are now, the best teams get richer, and those at the back languish on the treadmill of mediocrity. The better a team finishes at the end of the year, the larger its payout, which is then spent to improve its car. Sponsors spend more to get their names on better cars. Mercedes is always getting faster, and Haas has to watch them fly into the distance.

Listen to an audio version of this story on our podcast, Sports Illustrated Weekly.

This is the world Netflix entered when it released the debut season of Drive to Survive in 2019. The documentary series doubles as an F1 gateway drug; it’s Hard Knocks if Hard Knocks had the guts to brake late into a corner going 200 mph. The appeal isn’t complicated: The show follows 20 telegenic, highly competitive drivers and their teams as they attempt to push the limits of modern engineering and speed to victory. Over three seasons, it’s touched on the championship race but is most engaging when focusing on teams further back in the pack.

After Mercedes and Ferrari elected not to give Netflix access during the show’s inaugural season, the producers had no choice but to chase new characters outside the title fight, and they struck gold. Over the past few years, it’s made stars of drivers like Australian charmer Daniel Ricciardo, whose penchant for jokes has won him as many fans as his driving. The series opened a new world to a massive audience and formed a cult fandom in the process. More than 50 million F1 obsessives have streamed the series, and the sport has already felt its impact. F1 has a long, rich history of failing to capture the U.S. market, but the show has caused interest to boom Stateside.

More than 400,000 people flocked to Austin in October for the United States’ only F1 race, up from 258,000 in 2017. Television viewership has increased each season since the show began, tickets sold out for a new race in Miami in a matter of minutes and rumors are circulating about the possible addition of a third U. S. race soon. Not long ago, drivers could remain at least semi-anonymous stateside. Now, Grosjean and members of his cohort are often stopped for selfies and autographs.

The Frenchman was a central character in all three seasons of the series, which began following the 2018 season—Grosjean’s third with Haas. Joining the new U.S. team in ’16 was a natural next step for him after a junior career that rivaled Hamilton’s and a surprisingly successful four-year stint at Lotus during which he reached the podium 10 times.

“It shouldn’t really have been a contending car,” says F1 journalist and de facto Drive to Survive host Will Buxton. “It was a testament as to how good a driver he was.”

Haas purchases its engines from Ferrari. Had Grosjean won with them, his familiarity with the Italian giant’s technology would make him an appealing choice for a seat. But Haas’s car, even with a Ferrari engine, wasn’t great, and Grosjean took extra risks to compensate, leading to two tough seasons in 2016 and ’17 that moved him off Ferrari’s radar. Though Haas found some success in ’18, with Grosjean and his teammate Kevin Magnussen carrying the team to fifth place in the constructors’ championship, the next year it fell to ninth, and an even worse car in ’20 saw Grosjean finish in the top 10 only once. Midway through the season, he was informed he wouldn’t have a seat in ’21.

Grosjean had always been fast. As Magnussen tells it, “He’s always flat out. You never get 99% Romain. There’s only 100% Romain.” But after years of failing to live up to his potential, the frustration began to wear on him. He’d chase gaps that didn’t exist, and he developed a reputation as an aggressive—or even reckless—driver.

This wasn’t how Grosjean’s story was supposed to go. He had the talent, along with that something special: that thing that only racing drivers are born with that tells them to take a car to its limits. Had a few breaks gone his way, Grosjean could’ve been a world champion. Instead, he was out of the sport.

After a decade behind the wheel, his F1 career was coming to an end. And by the time he reached Bahrain in November 2020 he’d made peace with that. It was the 15th race on the schedule; only two would follow it. Grosjean just wanted to go out on a high.

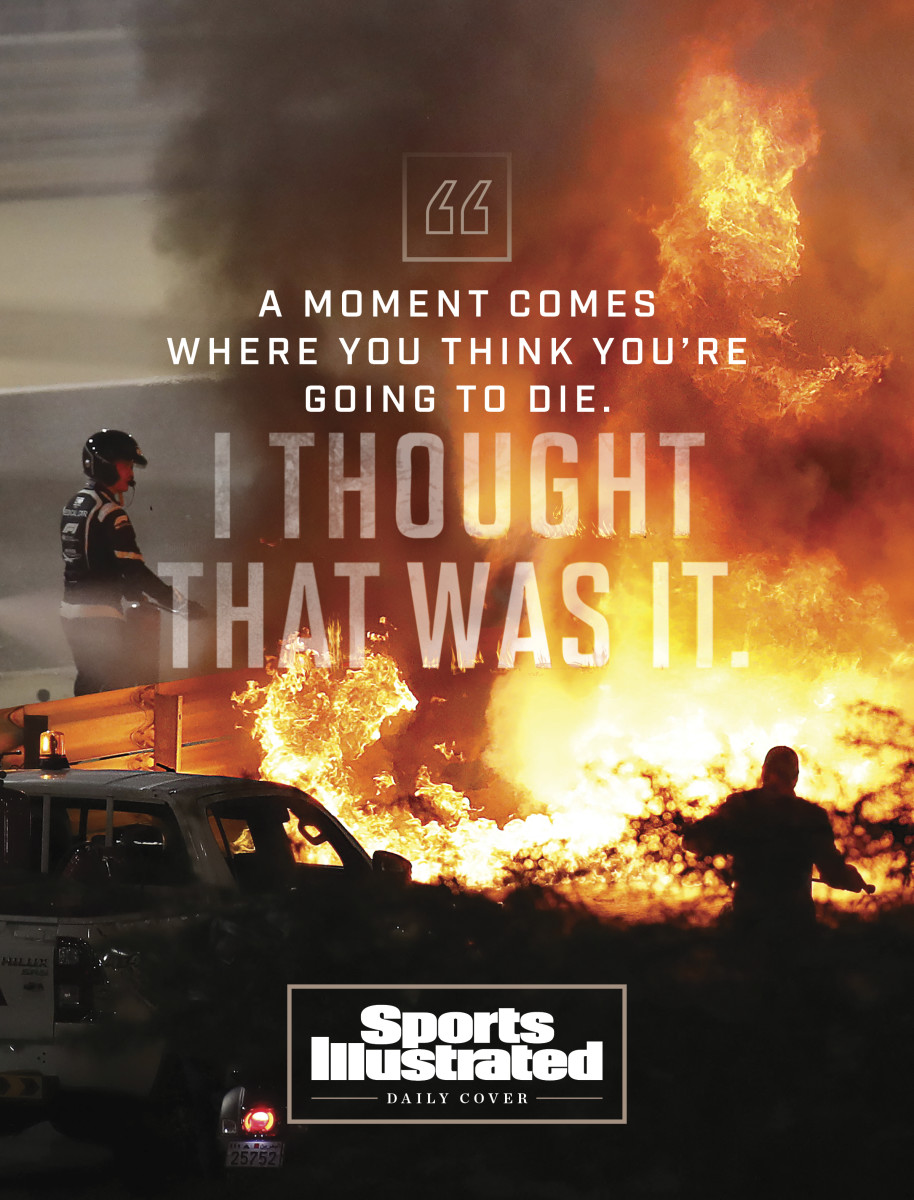

“A moment comes where you think you’re going to die,” says Grosjean, a year removed from the crash that nearly took his life. “I thought that was it.”

Death and F1 are well acquainted. Ayrton Senna, the Brazilian maestro that many on the grid today point to as their favorite driver, died in 1994 when his car flew off the track and hit a concrete wall at 145 mph, just a day after another driver died during qualifying.

Though a series of safety efforts were implemented following Senna’s death, the threat still looms. In 2015, 25-year-old Jules Bianchi was killed in a crash in Japan, and five years later, Anthoine Hubert—a 22-year-old F2 driver with a top-circuit future—died after a crash in Belgium.

Grosjean’s race in Bahrain looked promising through the first three corners. Starting 19th, he gained two positions coming out of the first, weaving through traffic as he shot down the track, and exited turn three into the straightaway with a chance to pick up a few more. “I normally always have bad race starts, and for once I had a good one,” Grosjean remembers. “I wish I hadn’t.”

One car pulled to the left, veering wide as sparks from the braking cars scattered across the night air. Two more blocked his path in front, and a third, driven by Magnussen, occupied the spot ahead to the right. Grosjean checked his mirrors and then checked again to make sure he was clear—there was no one there—and then pushed his car wide right at 150 mph to peel past those in front. He was faster than they were. He had a good line. He was in the clear.

“Until I saw the footage the next day, I didn’t know what happened,” Grosjean says. “I didn’t know if my suspension broke, or I hit a bump, or I spun on my own or had contact.”

Daniil Kvyat’s car was hidden in Grosjean’s blind spot. As the Frenchman tried to shoot through the gap ahead, his back right tire clipped Kvyat’s front left, sending Grosjean careening toward the barrier. He hit the wall going 119 mph, carrying more than 67 Gs. His car split in half on impact and set off a massive explosion.

“When you see an incident of a certain magnitude, there is an eerie silence that falls on the track,” Buxton says. “You only feel it on very, very rare occasions, and it’s when an accident is of such magnitude that everybody literally holds their breath.”

Grosjean’s fire suit was built to withstand the blaze for 12 seconds. That day, he sat in his shattered, melting car for 28 seconds, lodged between two sheets of twisted metal as the flames swallowed him.

“You cannot get lucky with fire,” says Guenther Steiner, the team principal at Haas. “I was just conscious that if he doesn’t come out in the next 20 seconds, he’s not coming out.”

For half a minute, drivers and fans watched, praying for something to give them hope. The seconds that passed felt like hours, and the plume of smoke and f lames seemed to only grow more intense. It seemed like the end. But some switch flipped in Grosjean’s mind; today was not the day he’d die. He gave one final push, forcing himself up and out of the car just before the flames engulfed the cockpit.

“How did he jump out?” another driver, Carlos Sainz, asked while watching footage of Grosjean’s escape. “That’s an act of God.”

That Grosjean survived is as close to a miracle as you might find. Despite the massive fire, the safety measures in place worked as they were supposed to. The front of the vehicle absorbed the brunt of the shock. The rear of the car split when the carbon fiber survival cell could no longer hold on to it. And the halo—a titanium ring around the cockpit—punched a whole through the barricade, preventing Grosjean from being impaled. Somehow, he escaped with only a badly sprained ankle and severe burns on his left hand.

When the halo was first implemented in 2018, some drivers—Grosjean included—scoffed. It was ugly, he thought. It’d take away from his peripheral vision and make it harder to drive. Looking back, Grosjean admits he was stupid. He didn’t think it could save lives, until it saved his.

There's a quote Grosjean shares, originally spoken by Senna: “If you no longer go for a gap that exists, then you’re no longer a racing driver.” Drivers have to ignore their fears. One wrong move, or a punctured tire or a force beyond their control could mean certain death. But they can’t let the thought creep in. As Magnussen tells it, once a driver is strapped into their car, it’s almost as if they’re transported to a different world where the danger doesn’t exist.

“There’s no place for fear, or doubt or panic, because if you do that, you’re cooked,” Grosjean says. Grosjean hasn’t watched “Man on Fire,” the episode of Drive to Survive chronicling his accident. It’s difficult, having the most traumatic moment of your life not only caught on film, but also neatly packaged for the world to see. In November he underwent what he hopes will be his final surgery stemming from the crash—a skin graft on his left hand that alleviated the pain he felt doing simple tasks, like bending his finger or slipping on his sneakers, and brought his total stitches count up to 130. “It’s just painful all the time,” Grosjean told Magnussen at a reunion in Detroit this summer. “Except when I drive.”

Something about gripping the wheel feels natural. Grosjean never considered stepping away from racing. He’s a driver; he needed to be on the track. He’d pondered IndyCar before the accident, after learning he’d lost his seat at Haas. The cars aren’t too different, and the road courses bend in a manner that plays to Grosjean’s strengths.

Around Christmas, Olivier Boisson, a French race engineer with Dale Coyne Racing’s IndyCar team stopped by Grosjean’s home in Geneva. It was a recruiting trip; Boisson was visiting his parents for the holidays in France and stopped by Switzerland on the boss’s orders. Boisson painted a picture of what racing in the U.S. looked like.

IndyCar had more parity, he told the driver; the gap between cars wasn’t as defined as it was in F1 —IndyCar purposely tries to maintain tight regulations to emphasize the importance of the driver. That meant that Grosjean could make up places in a race with less difficulty if he’d had a bad qualifying, especially in looser cars.

It all sounded appealing to Grosjean, except for one sticking point: ovals. Where NASCAR (or IndyCar races like the Indy 500) places a premium on flat-out speed, F1 is more about precision. And after the year he’d had, the unfamiliarity with the track and the dangers present with high-speed crashes on an oval, Grosjean decided he wouldn’t drive them his first season.

It was a compromise the team could allow. Still, a question remained: Could he win with Dale Coyne? It was hard to say, Boisson told him, but they’d have a better shot than Grosjean did with Haas. It took only three races to prove true.

Grosjean dominated the Grand Prix of Indianapolis—a road race held just before the Indy 500—qualifying on the pole and losing only as a result of a pit strategy error. In a previous life, he’d have been furious finishing second after starting at the front. But something changed, he says. When he removed his helmet and stepped to the podium for the first time since 2015, he was all smiles. His landing in IndyCar seemed like a match made in heaven, and one that happened, in part, thanks to Drive to Survive.

“All of these new fans that Formula One is finding in the States, they know who Romain is. They know his story,” Buxton says. “They know the difficulties that he’s gone through. They saw what happened to him in Bahrain. And then, all of a sudden, pow. He’s racing here.”

Over the rest of the season, he reached the podium two more times and ended his rookie campaign in 15th place, despite facing new tracks each week and sitting out the three races—of 16 total—that were run on ovals. His success didn’t go unnoticed. In September, he announced his move to a new team, Andretti Autosport, where he’ll race a complete season in 2022. He didn’t just come to the U.S. to fade in his final years. He came to win. And while Netflix might’ve helped him find a seat, it’s not the reason he’s kept it.

“Jimmie Johnson, the greatest NASCAR driver of all time, transitioned to Indy Car and was nowhere,” Buxton says. “If Romain had been nowhere, he wouldn’t be doing as well as he is. He wouldn’t have gotten the Andretti seat. He wouldn’t have the fan base that he does. That comes from results, and Romain is showing week in and week out that he’s still the racing driver he was.”

In the year since his accident, Grosjean says he’s had only a handful of flashbacks. A few in December, a few weeks after the crash, and then again during an IndyCar race in Detroit where his brakes caught fire, the smell of the burning carbon sent him back to Bahrain, and he flung himself up from the car and sprinted to find an extinguisher. But since then, he’s moved on.

There’s a feeling of relief, he says, being back in a competitive car. Occasionally, people will ask him whether he wants to return to F1. He still has the talent for it, Steiner says. But Grosjean looks at the field and doesn’t see a future there. There are only 20 seats, and, now 35, his options are limited.

“Maybe if I get a phone call from Mercedes, Red Bull, or Ferrari or McLaren, but that’s not gonna happen,” Grosjean says. “I’d just be one of the guys filling up the grid, and I don’t want that at all.”

F1 is in his past. For the first time in his senior career, Grosjean will race in a quick car and for a team with the resources to put him in contention to win. Winning a title this late would take the pace he’s had all his life and breaks he’s rarely had on the track. It would be an anomaly. Then again, maybe luck is finally on his side. He’s the man who walked out from the fire.

Read more of SI's Daily Cover stories here:

• Tom Brady Wins the 2021 Sports Illustrated Sportsperson of the Year

• How Steelers' Logo Helped Heal Pittsburgh After Synagogue Shooting

• Bowl Season Is Coming. And There Are Only 36 Pylons Left.