Twenty-Five Years Ago, Payne Stewart Delivered Pinehurst's Signature U.S. Open Moment

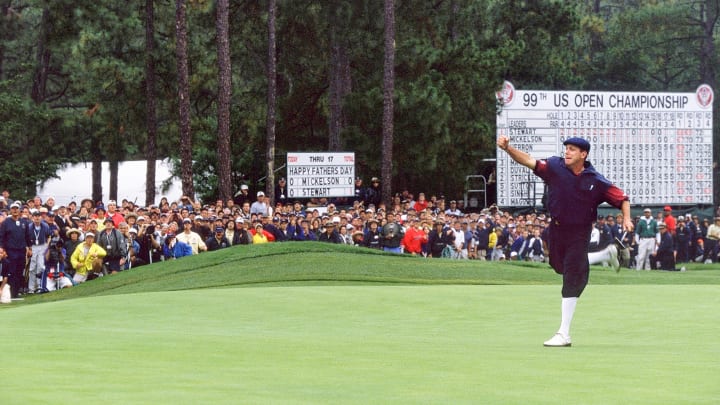

PINEHURST, N.C. — It is an enduring sequence of images emanating from the 18th green at Pinehurst No. 2. Donald Ross’s gem more than delivered in its first-ever U.S. Open, and there was golf’s flamboyant figure, Payne Stewart, holing a clutch par putt, celebrating with an outstretched arm and leg, a portrait etched in time.

In a moment, Stewart quickly extended his condolences to Phil Mickelson by relishing his rival’s impending fatherhood, with the birth of wife Amy’s first child a day away but the elusive major championship still a half decade in the future.

By converting that 15-footer, Stewart had claimed his second U.S. Open and third major title. It was a dramatic conclusion to a highly anticipated U.S. Open at Pinehurst, and his feat is immortalized with a bronze statue.

The day will always be remembered—how could it not be? And this year, of course, the U.S. Open returns to Ross’s hallowed North Carolina layout for a fourth time—25 years after Stewart’s triumph.

“I remember thinking, ‘That can’t go in,’” said Stewart’s friend, Paul Azinger. “You can’t make that putt to win the U.S. Open. But he did. He secured his legacy.”

And just four months later, he was gone.

The victory itself was monumental. Stewart won a third major and did so while taking on one of the game’s top young talents and also beating back another in Tiger Woods, who tied for third along with Vijay Singh.

But his death later that year came as such a shock, surpassed only today but how long it has been since it occurred. Stewart was killed when the private plane in which he was traveling on his way to the Tour Championship in Houston lost cabin pressure and crashed in a South Dakota field.

The golf world mourned, with the golf tournament later that week paused for a day so that players could attend his memorial service.

The victory was popular for many reasons, among them the way he had been denied a year earlier when Lee Janzen beat him at The Country Club in San Francisco. It also showed he had some excellent golf left with the potential to add to those 11 PGA Tour victories and three majors.

Stewart had such a classic, old-style swing that appeared effortless and was built to last. But he was set to enter a stage of great contentment, with an aura of nothing to lose, exempt into the major championships for years to come.

It remains difficult not to consider what might been. More wins? More majors? The Champions Tour? A Ryder Cup captaincy, no question. Stewart would have been 67 on Jan. 30 of this year, undoubtedly strutting in his trademark plus-four knickers.

“That could have been the end of his majors run, or it could have been in the middle of it,” said longtime friend Peter Jacobson. “His game was always unpredictable. He could pull a rabbit out of his hat at any time. This is something I don’t think you ever get over. You could always tell when Payne was around. Life happened to Payne. He was the life of the party. There was always something going on with Payne.”

Mickelson, Woods and Matt Kuchar are the only players from that U.S. Open who will be in the field when Wyndham Clark attempts to defend his title. Mickelson is now 53 and in the field due to the five-year exemption he received for winning the 2021 PGA Championship.

Woods, 48, a three-time U.S. Open winner who tied for third with Vijay Singh behind Stewart and Mickelson, received a special exemption this year from the United States Golf Association. Kuchar made it through final qualifying last week in Florida.

Mickelson had won twice in each of Woods’s first two full years as a pro in 1997 and 1998 and kept hovering in or around the top 10 in the world. His record in major championships until the U.S. Open in 1999 was good if not great, with no victories but seven top-15 finishes including a tie for sixth at the Masters won by Jose Maria Olazabal two months earlier.

Woods, meanwhile, was slowly putting together what would be an epic season, with most of the wins occurring later in the year. After his breakthrough win at the Masters in 1997, Woods found the going not as smooth in subsequent major championships. Some murmured that the major haul of titles predicted for him might not be on target.

But he won three times prior to the 1999 U.S. Open, including his first victory two weeks prior at Jack Nicklaus’s Memorial Tournament. The Saturday pairings put Woods and Mickelson in the second-to-last group ahead of Stewart and David Duval.

And it saw the veteran Stewart competing with the next generation and eating up the challenge. Although a win earlier that year at Pebble Beach was his first in four years, Stewart—who won the 1991 U.S. Open in a playoff over Scott Simpson—relished the tournament and the style of play it required.

That he was able to prevail—the only player to complete 72 holes under par, making that par putt on the final hole and striking that iconic pose—was the stuff of dreams.

So much, of course, has transpired since the time of his death a few months later.

Woods had just won the second of his 15 majors. Duval was ranked No. 1 in the world. Rory McIlroy was 10 years old.

And then there was Mickelson, who played the entire tournament carrying a beeper (anyone remember those?) and ready to leave at a moment’s notice if he wife, Amy, went into labor. Had Stewart not made the par putt, there would have been an 18-hole playoff the next day—at around the time the Mickelson’s daughter, Amanda, was born.

It was a tough loss for Mickelson, one he has always looked back on with perspective.

“I just felt going into the ’99 U.S. Open that to travel all the way across the country when we were so close to delivering our first child, I felt very determined to make that worthwhile and to get a win out of it,” Mickelson said. “It was really a shock when that did not happen. Granted, it was the way it was supposed to be … but at the time I really was surprised because I was playing well and I was very determined to win and just didn’t do it.”

Only a few weeks before his death, in what turned out to be the last big event he played, Stewart was part of a victorious U.S. Ryder Cup team at The Country Club. He reveled in that win as much as anyone.

Photos of Stewart celebrating dotted the aftermath but a far-less publicized scene played out on that final day. The Cup was clinched with Stewart in the final match still on the course against Scotland’s Colin Montgomerie, who throughout the day endured what was a shameful abundance of heckling and abuse from spectators.

Several times, Stewart tried to intervene, hoping to quell the noise and allow his opponent some peace. As they played the 18th, Stewart ended up conceding the point with both players on the green, picking up Monty’s ball in an act of sportsmanship during an emotional, tense day.

“It was a very difficult time, and the way he dealt with that situation I was in on the Sunday, with regard to his own performance, I’ll never forget,” Montgomerie said. “When he won the U.S. Open at Pinehurst, the first thing he said was he was he was on the Ryder Cup team, and he was thrilled to be on the Ryder Cup team—even more than he was winning the U.S. Open.

“It meant so much to him to represent his country. And to have drawn him against me, of all people, in the singles match—I’m sure it hurt his game, as well as it did my own. And it was a shame the way it finished. He’d had enough, I’d had enough, and he picked up my ball at the last and I’ll never forget that. Not all the memories are fine. But that match I will always think of with fond memories, of that game with him.”

Less than a year after his death, the PGA Tour named an award in his honor, the Payne Stewart Award, with its first recipients Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus and Byron Nelson. It is given to player annually who shows respect for the game while being honored for their charitable work.