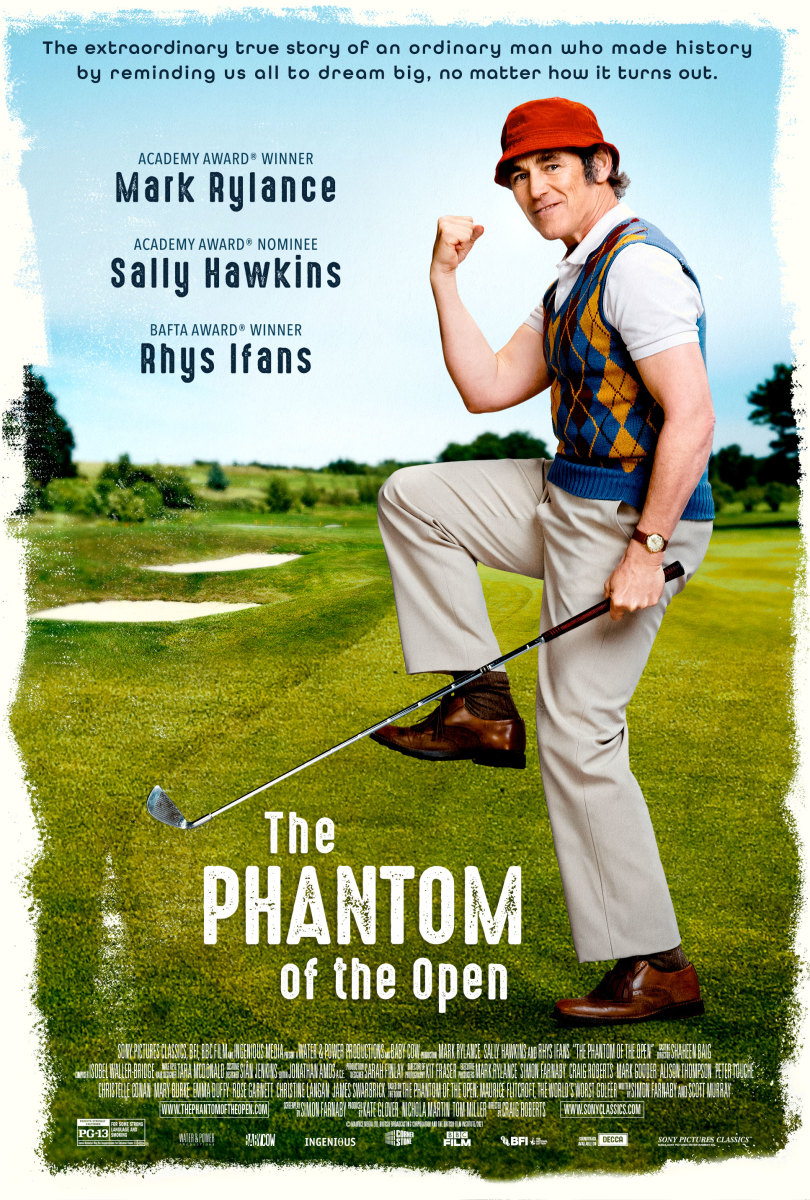

'The Phantom of the Open' Brings Maurice Flitcroft's Amusing, Inspiring Story to Big Screen

By day, Maurice Flitcroft was a British shipyard crane operator. Any other time beyond his early 40s, Flitcroft fancied himself as a professional golfer, though in reality, at best, he was a middling amateur. And his golfing exploits would most likely have gone unnoticed except for the fact that in 1976, during qualifying for the British Open, he carded a 49-over-par 121 to the embarrassing astonishment to R&A officials. The fiasco did not deter the relentless optimist from continuing to pursue his dream.

Simon Farnaby, who co-wrote "The Phantom of The Open: Maurice Flitcroft, the World's Worst Golf" in 2010, turned the book into a screenplay that was recently made into the movie “The Phantom of the Open,” which opens June 3 in the United States.

View: Trailer.

Morning Read contributor Tony Dear recently spoke with Farnaby and Oscar winning actor Mark Rylance, who plays Flitcroft in the film.

Note: The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Morning Read: You obviously couldn’t write the book immediately after the event, Simon, because you would have been 3 or 4 years old. But why did it not happen until 2010, and why was it another nine or 10 years before the movie happened?

Simon Farnaby: I read Maurice’s obituary in the Guardian (Flitcroft died March 24, 2007, at age 77). I’d grown up around golf — my dad was a greenkeeper and I could have turned pro at 16 — but I realized I’d never have a girlfriend, so I went into acting and comedy. When I read the obituary, I just loved the sound of this character — a dreamer, someone who did something that I would never have dared to do. And I just saw it as an opportunity to marry acting, writing, my old passion for golf and the chance to sort of connect with my dad. He was a mad keen golfer and played four times a week, every week, and would have played more if he could.

I suppose I made a sort of Flitcroftian leap and wrote a screenplay despite never having learned how to write one. Then I put it to one side and went off and did the Paddington movies and a film called Mindhorn and studied how to write films. Having learned how to do that and having researched the book with Scott Murray, and gone to Barrow-in-Furness to meet Maurice’s twin sons, Gene and James, I was in a much better position to write a good screenplay.

When I was researching the book and with Maurice’s sons in Barrow, I asked if they had any sort of keepsake — a postcard or letter — that might give me some insight into their father. They were each smoking a rollie and drinking sherry — they’re characters — and immediately said no, but they thought about it a second and one of them said “Hang on a minute. Yeah, we do.” And he pulled out a box and there was a document Maurice had been writing, a sort of autobiography. And he still had the menu from their flight to Michigan in 1988 (when Blythefield Country Club invited the family to the club for its Maurice G. Flitcroft Tournament).

MR: Why did you choose Mark for the part of Flitcroft?

SF: I’ve known Mark for a long time, and have loved everything he’s done. But it was really (director Craig Roberts’) idea. He asked what I thought about asking Mark Rylance to play Maurice. I said ‘of course,’ but never suspected Mark would get involved in such a niche story. Craig is very ‘can do’ though, while I’m a bit ‘can never do.’ I would have taken Mark at the drop of a hat, and in the end Craig persuaded me to ask. And Mark brought a sort of dignity to the part. Even when everything was going to shit for Maurice, he had a sort of quiet dignity about him and Mark played it perfectly.

MR: Do you follow golf at all, Mark? Did you know who Seve Ballesteros was prior to getting involved?

Mark Rylance: Yes, I did, and I know who Jack Nicklaus is and Arnold Palmer. My dad was a keen golfer. When we lived in the U.S. in the late 1960s and 1970s, he would volunteer at tournaments. He drove Clint Eastwood once in California. But he was very busy, so there wasn’t a lot of time for playing golf with me. And my grandfather loved lawns. He kept his lawn very tight and rolled, and we would putt and chip on it when I was a kid. So, I did play a little into my early teens, but it never went further than that.

MR: When Simon approached you with the script, what did you find appealing about it?

MR: It made me laugh and I was moved by it. There was a sort of Don Quixote aspect to Maurice that I really liked. He’d hear people out and listen to them say he’s the world’s worst golfer, but he’d disagree and say firmly “No, I don’t think I am.” If it was a tragedy, we’d see him use fisticuffs, but he honors his own dream, his own imagination of who he is. Not to a psychopathic or sociopathic level where he doesn’t hear other people or won’t listen to them, but he won’t speak or think badly about himself. That’s something I find very difficult personally. I can take criticism to heart and sort of lose my way. So, I admired Maurice very much.

And, of course, any comedy needs something that people take very seriously, so golf is a perfect matrix for comedy because people obviously do take it seriously. A lot of it just resonated with me. It was very rich. And I knew a little bit about Simon through my friend Mackenzie Crook (Gareth Keenan in the British version of “The Office,” Ragetti in the “Pirates of the Caribbean” trilogy and Rylance’s co-star in the stage hit “Jerusalem”) and the wonderful “Detectorists” TV show they did together. And Craig was very inspiring with his idea of bringing more imagination and color into British cinema. And it was really my first chance to do comedy in a movie, so I was really thrilled to do it. Plus, I hadn’t worked for nine months because of COVID, and they were willing to have a go during the pandemic, in the eye of the storm.

MR: Mark used the word ‘comedy’ there and of course it is a comedy first and foremost. But did you ever think it could be something else? There are some very poignant moments.

SF: I look for comedy all the time and love funny things, but because this was a true story I didn’t treat it like an out-and-out comedy like “Paddington” or “Mindhorn” or any of the other things I’ve done, because you have to stay true to the real person and have respect for them. I believe Maurice felt like he was genuinely good enough to play golf well. And I didn’t want people to laugh at him. I didn’t mind if people laughed at the authority figures (Rhys Ifans plays the gruff R&A secretary Keith Mackenzie).

They were more stupid than Maurice in some ways and really should have known better. With the comedy movies I’ve done, you’re always thinking about ways to make people laugh obviously, but with Maurice I was really curating what had happened to him, trying to make it entertaining, of course, but always trying to keep the purity of Maurice’s spirit. When I saw it in New York with an American audience, they were really howling throughout. Craig said it was one of the best screenings we’d had. People came up to me and were saying “This is the best movie I’ve seen in years.” But I also liked the screenings where people just nodded along and were quite quiet, but still enjoyed it. People reacted to it differently depending on where they were from and what they knew about the story.

MR: It definitely has the bones of a genuine comedy because it was quite farcical. But I’m sure you also didn’t want to ridicule Flitcroft. He was a good father and husband, a family man and a working man.

MR: Yes, definitely. Like Simon, I went up and spent time with his son James and a whole bunch of his grandchildren who carry his name in that community. So, we’re landing them with this reputation, which they can certainly change in pubs and restaurants, but this could have a big effect on their lives. And if we had painted him as some kind of goon or idiot then that would have made life very uncomfortable for them, and it wouldn’t have been a very nice feeling for us either. But I think they are happy and pleased with it.

It’s different with the son of the guy I base my character on in “Jerusalem” — a ne’er-do-well who lives in a camper in the woods drinking and selling drugs. He’s having great difficulty with the reputation his father had and I’m trying to figure out a way of how to correct that for him. So, you have to be really careful, even with people who have passed away because of the effect you can have on their surviving family members.

MR: It obviously wasn’t a motivator in any way, but the movie might put Barrow-in-Furness on the map.

SF: Ha. It’s a very unusual place. They call it the “Insular Peninsula” — one road in one road out. But the town has a great sense of itself and the people have a great self-deprecating humor. There’s a statue of Emlyn Hughes (played 474 games for Liverpool soccer between 1967 and 1979) in the town. He was its most famous son. When I was with the twins, they threw beer cans at it and shouted “That should be our dad up there” — joking, of course. We did a screening in Barrow and it was an absolute riot, probably the most fun one we did. It was packed and there was so much joy there. I think they embrace the association with Maurice even if they didn’t know who he was.

MR: Tell us about the Seve scene in the locker room at Formby Golf Club. It didn’t actually happen, so it needed some creativity on your part.

SF: Seve was always my favorite golfer, and I just wanted a scene with a pro. It could have been Nicklaus or Miller, but I wanted someone who would have welcomed Maurice rather than ask what he was doing there. Seve learned the game with a stick on the beach, which was quite like Maurice before his mail-order clubs arrived. So, it was a confluence of many things. I did have to be a little creative, but I stand by it. We actually thought about getting Seve’s son Javier to do the part. And he wanted to, but he’s in his 30s now and Seve was 19 at the time so it probably wouldn’t have worked so well.

MR: You know, if I’m remembered for one scene in any movie I ever do, I hope it’s that one with Seve in the locker room.

MR: Mark, tell us about the golf scenes. Were they hard to do? In a lot of sport movies, they take an actor who isn’t good at that particular sport and try to make them look like a world beater, and it rarely works. Here, we had an inexperienced golfer playing a bad golfer. So, it worked much better. Would you say you’re about the same standard as Flitcroft was in 1976?

MR: I would say Maurice was probably a better golfer than me. But the more takes we did, the more I understood the fascination of hitting a little ball with a piece of metal and seeing it go where you imagined. I understand the addiction and the thrill of it. I did swing a club as a kid, but I have no technique and don’t understand the science of it. And it was hard to swing while trying to copy Maurice’s movements.

SF: I’d say technically Mark’s swing is actually better than Maurice’s was, but Maurice played a lot more, so had many more repetitions. Mark won’t mind me saying this, but he had a sort of a clown’s face, in the old sense of the word, which is exactly what I wanted. A sense of just going and seeing what happens. And sometimes we got very funny results, and it just worked perfectly.

MR: Simon, you played a French golfer, someone that Maurice played with in qualifying one year.

SF: He was the one person who didn’t want to be interviewed for the book or appear in the movie. I can’t actually remember his name, but he didn’t want to be associated with it. So, I played a French golfer who was paired with Maurice and sort of looks down on him. I was a little nervy hitting the shot, but it did actually go about 220 yards down the middle. His look — the hair and the trousers — was based on Johnny Miller.

MR: It was about an hour into the movie when I told the people I was watching with that this actually happened. They had been enjoying it up to then, but then seemed to enjoy it more after hearing that it was a true story.

SF: Yes, I’ve heard that a lot. I know some people who said they watched the movie and at the end wish they’d known it was a true story — even though it says it’s based on a true story. Actually, some execs asked if we should put some real footage in at the start. I said no, because I thought the audience would then be comparing the real footage with Mark’s performance or Mark’s impression of Maurice, and I didn’t want that.

MR: Lastly Mark, has this raised your interest in golf at all? Will you be watching the Open at St. Andrews?

MR: Yes, it really has. I think it’s magical. I’m not so keen on urban courses. I think golf should be restricted to the links and wildernesses. Some of the courses we shot the movie at had tower blocks around them, and I just thought the golf course should be an urban park for children and especially with the growth of population. But I think the links courses are genius, and the movie definitely has raised my love for the game, and really for all amateur endeavors. I think we should be celebrating actors, golfers, swimmers, runners, painters, any one that doesn’t necessarily make their living from whatever it is they do and are brilliant at it, but really just anyone who enjoys something and has a good experience at an amateur level.