Bill Johnston: A fading story worth revisiting

It’s early 1953. Bill Johnston steers his road-worn Mercury into the dealership in Provo, Utah. He parks but doesn’t turn off the engine. He’s afraid the car won’t restart. So as he shops for new wheels today, he isn’t bargaining from a position of strength.

As he enters the showroom, Johnston immediately spots two beauties. One is a sweet, burnt-orange Mercury convertible. The other is an attractive female employee crunching numbers at a desk. She has reddish-brown hair and, Johnston thinks, “the greatest smile I’ve ever seen.”

A salesman comes over to greet Johnston. He is a familiar golfer who plays at Timpanagos, the course where Johnston is head professional. During a test drive, Johnston presses him for information and learns that the bookkeeper’s name is JoAnne Whitehead. “I’ll buy this convertible,” Johnston tells him, “if you get me a date with her.”

Back in the showroom, the salesman approaches Whitehead. He tells her about Johnston’s request and offers to split the sales commission if she goes out with his customer. She answers emphatically, “No!”

Outside, the parked Mercury is where he left it, engine still running. Johnston buys the convertible.

◼ ———— ◼

Bill Johnston ambles through the gate onto the sunlit patio of the Biltmore Country Club’s Adobe Restaurant in Phoenix, Ariz. He is as nimble and light on his feet as any 94-year-old would hope to be. His pace is careful but lively. He still golfs a few times a week.

The hair above his lined face is white and wispy, but he somehow exudes enthusiasm behind his glasses. You probably haven’t heard of Johnston, but here at the Biltmore course, he’s a celebrity. Waitresses, bartenders and other club members call out to him as he passes. “Mr. Johnston. It’s nice to see you. How are you today?”

The greetings follow him through the restaurant like a crowd doing The Wave. I feel like I’m walking with Paul McCartney as we’re led to a table.

He should be a legend here. He built this place, sort of. He helped design and construct the club’s 18-hole Links Course in 1979 during a short stint as head pro. He was a club professional for 42 consecutive years at assorted western clubs. One of his regular golfing buddies said Johnston still considers himself a club professional first.

That says a lot because there isn’t any part of golf that Johnston hasn’t taken on and conquered. Johnston played in 335 PGA Tour-sanctioned events, including 196 on what is now called PGA Tour Champions.

◼ He won two PGA Tour titles, the 1958 Texas Open and 1960 Utah Open. He won 11 state championships.

◼ He was a star collegian at the University of Utah. He is enshrined in three different Halls of Fame.

◼ He designed and built golf courses, sometimes even building the adjacent housing developments.

◼ He competed multiple times in all four major championships and played with Sam Snead, Jack Nicklaus, Gary Player, Arnold Palmer, Jimmy Demaret and pretty much everyone who was anyone in the middle third of 20th century with the exception of Ben Hogan. How many living men can make such a claim? Only a handful.

The name Johnston still doesn’t ring a bell? Well, his era, like Hogan’s and Snead’s, has come and gone along with those who recall it.

Plus, the PGA Tour seems to have forgotten this former champion. Surprisingly, Johnston has a page in the players section at PGATour.com, but you won’t learn much about him there. His bio is pretty spartan. Even Spartans would look at it and ask, “That’s it?”

Here’s his official website bio: Bill Johnston, United States.

That’s all. No birthdate (Jan. 2, 1925). No birthplace. (It’s Donora, Pa., but he moved to Ogden, Utah at age 4.) No picture. (He played tour events over a span of 51 years and the PGA Tour has no head shot?) No college. (University of Utah, where he’s in the school’s Sports Hall of Fame.) No place of residence. (Phoenix.)

No achievements. No mention of his two tour victories.

Johnston has often felt like a club-pro outsider and a second-class tour member. He remembers the meeting in West Palm Beach, Fla., with PGA Tour commissioner Deane Beman and a handful of older players who helped organize the events that turned into the original senior tour.

Bill Johnston played in 335 PGA Tour-sanctioned events — winning twice — and multiple majors, but his accomplishments go well beyond the spartan pages of the PGATour.com website. [Photo: Bill Johnston]

“We thought the tournaments were going to be full fields of 144 players,” Johnston said. “Well, Gardner Dickinson, Dan Sikes, Bob Goalby and a few others decided that we’d have only 52 players. They were pretty damn selfish, I’ll tell you that.”

The tour initially took 26 players off the all-time victory list and 26 off the all-time money list. Johnston made it by virtue of his wins the first year, but, he says, “because I got in ahead of some of their friends, they changed that formula the next year.”

No longer exempt, Johnston was forced to play in a four-spot qualifier for “non-qualified members.” He succeeded four times and won enough money to earn exempt status via the career money list.

Club pros were never particularly welcome at any PGA Tour event, especially when purses were miniscule in the 1950s and ‘60s. Club pros who could really play, like Johnston, were particularly unpopular. And still are, if you want the truth.

“All you used to hear about at player meetings was ‘the goddam club pros coming out and winning our money,’” Johnston said. “My comment always was, ‘If you can’t beat a club pro, why in the hell are you out here?’

“One night at the 1958 Texas Open, Bob Rosburg got up and was badgering everybody. I finally said, ‘Rossie, are you really afraid of guys like me?’ That kind of quelled it. I won the tournament that week and beat Rosburg by three shots.”

Rosburg, a long-time golf broadcaster, passed away 10 years ago. He doesn’t have a mug shot or profile information on his PGATour.com page, either, believe it or not. So maybe it’s just easy for the tour to forget about its former players.

It’s too bad Johnston’s profile is conspicuously absent because it would be fairly conspicuous. He caddied as a teen. He served on a submarine in the Pacific during World War II. He designed and built golf courses while playing 335 pro events. He organized and ran tournaments and pro-ams for members. While building one of his courses, he somehow found time to take flying lessons and get a pilot’s license, fulfilling a lifelong dream. The only part of golf he maybe didn’t excel at was public relations.

On this subject, Johnston can’t hide a bemused smile, as if he knows something he’s not telling. He talks briefly about his time as a player representative on the senior tour council and how he was often the lone dissenter on 11-1 votes. He stuck up for players like himself, the outsiders and lower-level tour players who didn’t have grand early careers, to try to level the playing field against the wealthier household names who largely ran the tour for their own benefit and were fiercely protective of their second-chance gravy train.

“I was there to represent everybody,” Johnston said, “not just my tour buddies.”

Among his notable run-ins, Johnston questioned the career earnings figure attributed to an international player who was going to gain exempt status because of those earnings. Upon further review, the numbers were inflated. So the player lost his free pass and had to go through qualifying, instead. He succeeded, went on to win multiple senior titles and became a minor tour star. However, his brother was a senior vice president of senior tour operations and never forgot Johnston’s call-out.

In another case, Johnston requested minutes from a contentious players council meeting and instead of getting them, earned a crude rebuff from commissioner Tim Finchem. “Jimminy, I thought you guys worked for the tour players,” Johnston told him, “not the other way around.”

Not long after that, Johnston said he and his playing partner were uninvited to the two-man Legends event in Savannah, a popular and lucrative senior stop.

So the fact that Johnston’s profile has been all but scrubbed from public PGA Tour records doesn’t surprise him. He chuckled about the website when told how barren his page was. He doesn’t care, not a lick.

But I do.

◼ ———— ◼

The 1953 Mercury owner’s manual and accepted standard procedure say to bring a new car in for the recommended 3,000-mile checkup. It’s not a law on the books, but it’s close enough.

Johnston quickly racks up the necessary miles on his new convertible in a few short months. He’s got a good reason to return to the Provo car dealership — JoAnne, the beautiful bookkeeper.

He waits for his car to be serviced. He also waits to hear from the maintenance department manager —the head mechanic. Johnston also convinces him to ask the bookkeeper again if she’ll go on a date with him.

Her answer is audible in most of the showroom:

“Absolutely not!”

◼ ———— ◼

What Bill Johnston learned about war is simple: You’ve got to be lucky.

He graduated from high school in Ogden, Utah, on June 1, 1943. On June 3 he was sworn into the U.S. Navy. He wanted to be a fighter pilot, but he had already turned 18. The Navy was training only 17-year-olds for pilots. So he wound up in the submarine service.

After six months of training in New London, Conn., Johnston, who barely met the Navy’s 125-pound minimum weight to enlist (he ate an entire bunch of bananas before his weigh-in) was patrolling Guam and the South China Sea aboard the U.S.S. Sea Fox.

After his first patrol — patrols typically lasted 60-70 days — the Sea Fox pulled into Guam and Johnston went to sick bay with tonsillitis. It looked as if Johnston wouldn’t recover in time for the next patrol, especially after fainting while reaching for a door, so he was transferred to the U.S.S. Tang.

“I didn’t want to have to get to know another 80 guys,” he said, so he did everything he could to get those orders rescinded. He succeeded and rejoined the Sea Fox, which left Guam a few days before the Tang. Two weeks later, the Tang was sunk by one of its own torpedoes, which submariners knew was not uncommon.

“If a torpedo misses the target, sometimes it’ll circle back and get you,” said Johnston, a yeoman torpedoman. The Sea Fox had a close call on its first patrol before Johnston came aboard. A torpedo missed its target, circled back toward the Sea Fox and barely missed hitting its conning tower.

Another time, the Sea Fox surfaced off the coast of Honshu, one of Japan’s southern islands, and a lookout spotted a train. The captain ordered the five-inch deck gun into action for some target practice. Bad idea.

“Well, a bunch of Zeros came flying over that hill so fast, we had to make a crash dive,” Johnston said. “We damned near got nailed.”

Once, a plane that turned out to be friendly didn’t return its identification confirmation signal as per protocol, so the Sea Fox had to assume it was an enemy. A crash dive was ordered. “But the officer of the deck forgot to blow the negative tank, which provides positive buoyance for just a second,” Johnston said. “We went down like a rock. We don’t even know how far down we sank. The scale only went to 600 feet, our maximum limit, and we went well below that.”

It took six hours for the crew to pump out enough water to get back to periscope depth.

During a stay in Honolulu after his third naval patrol, Johnston was a dewsweeper, playing golf every day for two weeks at four nearby courses. [Photo: Bill Johnston]

The Sea Fox had one serious skirmish with the Japanese Navy. Just south of Japan, the sub surfaced in the fog in the middle of a huge convoy and quickly fired off six torpedoes. “We heard some explosions but unless you can confirm it, you don’t get credit for sinking anything,” Johnston said. “We sure as hell couldn’t stay around to watch.”

The Sea Fox made another crash dive but its rudder stuck. All it could do was circle helplessly below. Within a few minutes, the crew heard depth charges exploding along the convoy’s perimeter, where the Japanese destroyers expected the sub to be. “So the rudder sticking might’ve saved us,” Johnston said.

The Sea Fox returned to Honolulu after Johnston’s third patrol. He planned to catch up on his sleep during his leave. Then he heard the Royal Hawaiian Hotel had eight sets of golf clubs for use, first-come, first-serve. He rose at 5, grabbed a set and played golf every day for two weeks at four nearby courses. “That got me interested in golf again,” said Johnston, who had caddied and played irregularly in Utah.

According to the Navy’s points system, Johnston had earned enough credits to muster out of active duty. The atomic bombs had just been dropped and the war was effectively over but the Sea Fox was going back out on patrol. “No one was enthusiastic about that, as you can imagine,” Johnston said.

The Navy let Johnston out of combat but put a freeze on him, keeping him in service for eight more months. He spent the rest of his time at the Mare Island shipyard north of San Francisco, where he helped decommission the Baya, another submarine.

The island had an 18-hole golf course. When his captain found out he was a golfer, Johnston was “ordered” to play with him three times a week. “I’d say, Captain, I can’t go today, work is piling up,’ and he’d say, ‘Do it on the weekend,’” Johnston said. “So I had only one weekend off.”

The Navy offered him a promotion to chief if he re-enlisted but Johnston told the Navy he wanted to go to college and become a golf pro. He departed the Navy in May, 1946.

“If I’d been a fighter pilot, I probably wouldn’t have made it through the war,” Johnston reflected. “I was a little on the reckless side.”

The wannabe pilot became a submariner and later, a golfer. It happened that way only because he was born a few months too soon.

You’ve got to be lucky.

◼ ———— ◼

Johnston wheels his shiny convertible into the Provo car dealership again. It’s time for a 6,000-mile checkup and, also, his last stand. He can’t pester the bookkeeper again after this and he knows it.

While his convertible is up on the lift for an oil change, Johnston convinces the sales manager to ask the bookkeeper one last time for a date. He expects another rejection. Instead, she tells the sale manager, “Have him call me.”

Johnston does. Their first date falls on the Fourth of July. They go to a movie, which is about all there is to do in Provo. He pays more attention to JoAnne than the movie, anyway.

Afterward, he drives her to Timpanagos. She knows nothing about golf and Johnston is at a loss to explain the game that is his life. It’s too dark to show her how he could hit a golf ball so he tries a different approach. “Why don’t you lie down on the green and feel how soft the grass is?” Johnston asks.

Well, she huffs, she has no intention of doing any such thing. Johnston tries to explain that he didn’t mean anything improper but realizes this misunderstanding may mean this is their first and last date.

When JoAnne returns home, she evaluates her suitor for her mother: “I think he’s some kind of nut.”

◼ ———— ◼

You knew you’d arrived when you got mentioned in a newspaper headline. For Johnston, it happened at the 1956 PGA Championship, which was contested in a match-play format at Blue Hill Country Club in Canton, Mass.

Johnston, a club professional and a fledgling tour player, knocked off several tour regulars on his way to a quarterfinal match against Walter Burkemo, the match-play killer of the time. Burkemo had a 23-1 record. Johnston beat him, advancing to the semifinals and earning an invite to the 1957 Masters.

“At that time, back East they thought that anything west of the Mississippi was Indian country or something,” Johnston said. “My headline in one the papers—I don’t remember if it was the Globe or the Herald, said, ‘The No-one from Nowhere, Utah, reaches semis.’ I thought that was a hell of a headline.”

Johnston was excited about the prospect of playing legendary Sam Snead in the semifinal round. Except Ted Kroll upset Snead and then Johnston suffered a letdown and lost to Kroll. “I shouldn’t have had a letdown,” Johnston said, “but I did.”

The 1957 Masters was a thrill for Johnston. He was paired with Arnold Palmer in the third round. It was the first year the Masters instituted a cut. Only the low 40 players and ties played on the weekend. Johnston birdied 17 and 18 the second day and made the cut. Defending champion Cary Middlecoff didn’t.

The low 24 finishers got automatic invites back. Johnston tied Lloyd Mangrum and Lawson Little at 299, 11 over par, and finished 28th, two strokes away from earning a return invite. He didn’t make it back to Augusta again until 1964.

Johnston enjoyed a couple of moments with Palmer in 1960. He was in the final round’s final pairing with Palmer at the 1960 Palm Springs Desert Classic. Palmer went on to win by three over Fred Hawkins. It was around then that Johnston decided his favorite pairing was with Palmer and Gene Littler. I thought the reason was going to be tempo-related or a putting thought or something technical. I was wrong.

“We didn’t have pin sheets or yardage markers back in those days,” Johnston said. “So if the pin is in the back of the green, you can shoot for the flag if you’re with Palmer and Littler because if you go long, there were enough people in the gallery behind the green to stop your ball.”

Johnston delights in my surprise at the unexpected punchline, giggling like a kid who got away with something.

The other Palmer moment happened at the 1960 British Open at St. Andrews. Johnston made it through the 36-hole qualifier at the Old Course and the New Course, then survived the cut.

Johnston was playing up the 18th fairway in the final round just as Palmer, who began the day four strokes behind Kel Nagle, was coming off the first tee. Johnston gave his fellow Pennsylvanian a thumbs-up signal and Palmer waved him over.

“We shook hands in the middle of that big open area between those two holes,” Johnston remembered. “My god, the screams and yells that went up when we did that. I said, ‘Arnie, I feel like I just won the tournament!’ He got a laugh from that.”

Nagle edged Palmer by a stroke. Johnston finished 26th. “I won about $126,” Johnston said with a laugh.

The results made him feel better about his first trip to Great Britain. It hadn’t gotten off to a good start. The closest lodging Johnston could find was at the Gleneagles resort, several rugged driving hours away by car in those days, and Johnston got lost a few times on the Scottish roundabout intersections.

Then he cruised into St. Andrews, saw the ancient stone buildings and church steeples and a golf course that was the color of… straw?

“I’ve got tears in my eyes,” Johnston recalled. “I thought, 'Oh, god, why did I spend the money to come over here for this?”

Still upset, Johnston walked into the locker room. The first player he saw was Argentine gentleman Roberto de Vicenzo. “Roberto says, ‘Beel, how you are?’ and that got me laughing,” Johnston said. “That made me feel better.”

Johnston also heard that Bob Sweeney, an American amateur, had withdrawn. Johnston rushed over to the nearby Scores Hotel, where Sweeney had booked a room, and scooped up Sweeney’s reservation for himself and his wife (whose identity you may be able to guess).

“It was beautiful to just walk across the street to play instead of driving for hours,” Johnston said. “We spent ten days there with three meals a day, including tea and crumpets. The bill was $95. But we had to add a tip.”

Johnston and his wife went on to Paris for the French Open. Rain plagued the tournament, but Johnston shot 66 in the opening round and still led after a second-round 70. Peter Thomson inched into the lead after the third round.

Johnston played with de Vicenzo the final day. “He’d drop a ball on the tee and hit a brassie —a 2-wood — off the ground and he was wild as hell that day,” Johnston said. “But he still shot 63 and beat me by two.”

The Duke of Windsor followed Johnston’s pairing around the last 18 holes and confided in Johnston, “I sure want an American to win.” Johnston replied, “So do I. I’m the only one left in the field.”

I ask Johnston for the most memorable shot of his golfing life. He tells me about the 1960 Utah Open at Salt Lake Country Club, nestled in the foothills of the Wasatch mountain range. Johnston was four shots behind Doug Sanders going into the final round and a couple behind tour stalwarts Ken Venturi and Art Wall.

The Open featured a Calcutta wagering pool and some host club members had bought their local guy, Johnston. The Calcutta paid seven places and Johnston was in seventh after three rounds. Their advice to him before the final round? “Just see if you can stay there.”

Johnston came to the final hole tied for the lead with Bill Collins at 20 under par. The 18th hole was a risky par 5 that twice crossed canyons. Collins found the fairway off the tee but had a downhill lie and doomed his second shot into a canyon. Then Johnston hit a beautiful a 3-iron shot. The ball landed on the green and nearly hit the pin as it rolled 8 feet past. He made the eagle putt, shot 63 and won by two strokes over Wall.

“The cheers that went up when I made that putt echoed throughout the canyon,” Johnston said. “Venturi was on 16 and later said that noise upset him so bad that he would never return to Salt Lake. It was probably the members who bought me in the Calcutta. They won the whole danged thing.”

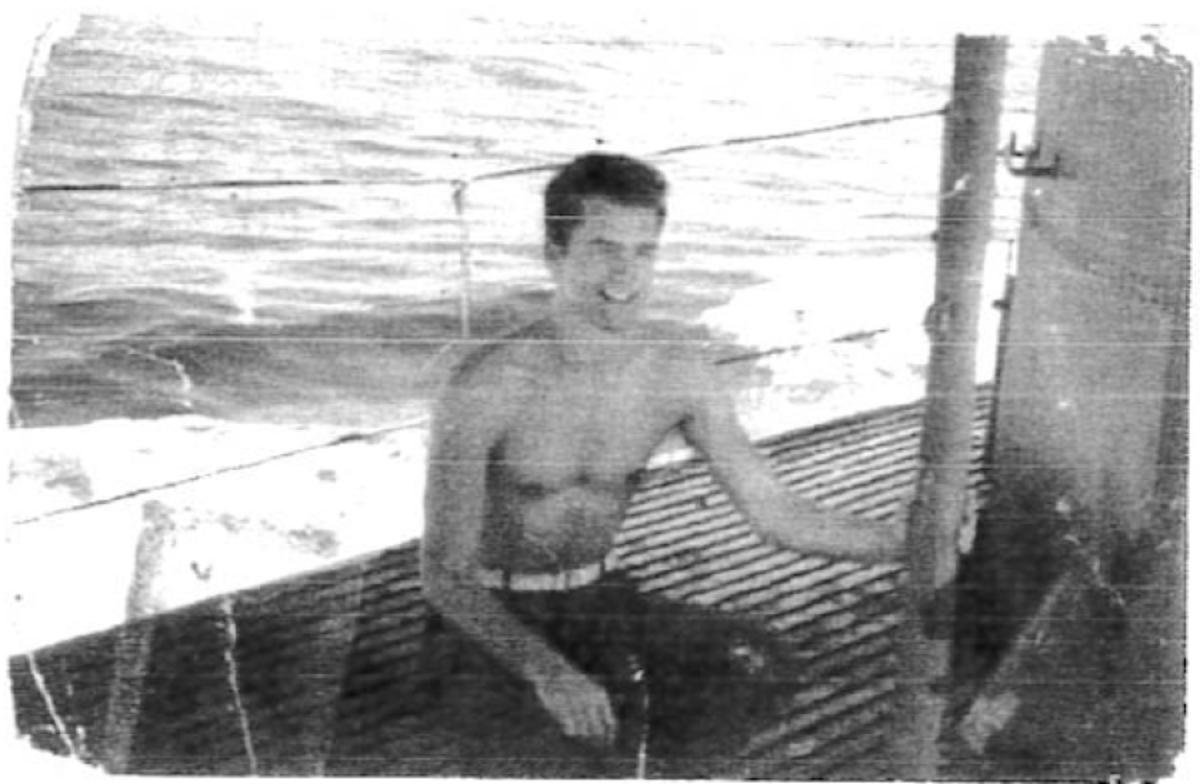

Bill Johnston on the deck of the USS Sea Fox submarine following his third patrol in 1945. [Photo: Bill Johnston]

Johnston’s least favorite career moments were mostly in the United States Open. It should have been a good event for him. John Gaquin, a PGA Tour official, nicknamed him Chief Straight Arrow for his accurate driving. Johnston hit a lot of fairways and greens, but said he was a terrible lag putter.

“I could make four- and five-footers galore,” Johnston said, “but I left myself a lot of those for my second putts.”

In 1953, Johnston advanced through a qualifier at Salt Lake Country Club that he thought got him into the U.S. Open at Oakmont. He arrived in Pittsburgh and was dismayed to learn he had to play an additional 36-hole Monday qualifier to get in the field.

Johnston successfully made it into the Open but missed the cut. He thought it was unfair to force qualifiers to endure an exhausting 36-hole day on the eve of the Open and said so in a letter he sent to USGA czar Joe Dey. Well, Dey ruled with an iron fist. He was not a man to be questioned.

“In the next seven Opens I played, I teed off dead last every time except once when I teed off next-to-last,” Johnston said. “I never got a tournament pairing, I was always put with qualifiers. In 1960 at Cherry Hills, I made the cut and Dey put Rosburg and I at the end of the field for the last 36 holes — after the leaders. They were picking up garbage cans and trash behind us. Rosburg was miserable.”

At the 1962 U.S. Open at Oakmont, Johnston was last off the first tee at 3:20. Because the first fairway was a blind landing area, play backed up and Johnston’s group didn’t tee off until 5:40 p.m. Johnston wanted to quit at 15 because of darkness but Dey personally came out and said if his group didn’t finish, they’d be back in position the next morning at 7. So they played on, finishing on an 18th green lit by parked cars’ headlights.

Playing late in the day back then was even worse because there was a rule against repairing ball marks. “I had to chip on some greens, it was so bad,” Johnston said of the ’59 Open at Winged Foot. “Going off last was terrible. Dey was an authoritarian and very vindictive. All I did was make a suggestion and I got a letter back from him in which he told me to go to hell.”

I can see the obvious problem Dey had with you, I tell Johnston. What’s that, Johnston asks?

“You didn’t follow his advice.”

◼ ———— ◼

Somehow, Johnston convinces JoAnne the bookkeeper to go out on a second date. Then comes a third. Then a fourth. And more.

Six weeks after their first outing, Johnston gives JoAnne a ring and says he’ll see her again in a few months. What, she asks in disbelief? Well, Johnston, explains, I’ve got to go on the road to play tournaments and catch up to the tour. She doesn’t know about golf. This is a shock. She is upset.

They talk some more and Johnston finally suggests, “Well, if you want to go along, let’s get married.”

On Sept. 3, two months after their first date, they marry at her home. Johnston isn’t a Mormon, unlike JoAnne’s family, so her parents aren’t thrilled. But Johnston doesn’t smoke or drink, so he’s somewhat acceptable.

They go to Grand Junction, Colo., so he can play in a tournament. They return to Provo, where Johnston works at the club for a week, then they go to Reno for another tournament.

This is their honeymoon. It is more than acceptable.

◼ ———— ◼

The next 64 years were a blur, if that’s possible, a wonderful 64-year adventure.

JoAnne and Bill had four sons — Brad, Blake, Brice and Burke — and JoAnne herded them all to as many of Bill’s tournaments as was feasible.

When Johnston talked himself into a job as the original Frontier Airlines’ director of golf, which came with perks such as free or discounted air tickets for himself and the family, it was as far removed as possible from his uninspiring first golf job.

Johnston’s degree in marketing and management from Utah got him hired to be the pro at a course in little Vernal, Utah. He drove there in his 1940 Oldsmobile, which he remembers because it burned as much oil as it burned gas. He learned it was actually a drinking club —Utah was a dry state then. Only one member played golf. When Johnston asked to see the course, he was shown to some rolling farmland.

“This is where you’ll have to build it,” he was told.

That became his first design, the Dinaland Golf Club. There were eight more courses to come, including the Dominion Country Club, which later became a popular stop on the Senior Tour in San Antonio.

◼WATCH:Bill Johnston on golf course design

Those Frontier days seemed a far cry, too, from his early attempts at the still-loosely organized PGA Tour. H.G. Godbey first met Johnston when he was with Frontier Airlines in the 1970s and Johnston created a big pro-am for Frontier that mirrored what the early senior tour was trying to do.

“The first year Bill joined the tour, he had to Monday-qualify for everything,” said Godbey, who lives north of Tucson and still joins Johnston for an occasional golf round. “He got in a couple times out on the West Coast. This tour official comes up to Bill and says, ‘You’ve got to pay a public relations fee.’ It was $3 a week, which was a lot considering the tournament entry fee was $15. Bill thought it was strange but he paid it. Then he checked around and learned the fee was being charged only to club pros and qualifiers, not regular tour players.

“So Bill gets in the next week and the guy comes up to him on the range and says, ‘Bill, I need your money or you can’t play this week.’ Bill turns to the guy next to him hitting balls, which happened to be Tommy Bolt, and asks, ‘Tom, did you pay your public relations fee?’ Bolt, in his usual manner, said, “What in hell are you talking about, Bill?’ And that was the end of the public relations fees.”

Johnston was never shy. He created that Frontier Airlines event, which lasted until the mid-1980s, and got his nice Frontier deal because he read in the airline magazine while on a Frontier flight that the airline had earned $15 million the previous year.

So Johnston wrote to Al Feldman, Frontier’s chairman, and told him why he needed to sponsor a pro-am similar to the Crosby (now the AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am), only with club pros instead of tour pros. Each club pro would bring a team of three amateurs, who would play with a different pro each round.

“Feldman bought the idea,” Godbey said. “Frontier served 80 cities in 17 states and the tournament would be a way to showcase Frontier’s warm-weather destinations. Frontier needed somebody in the company to work with Bill and I was the only one who played golf. So I was assigned and away we went.”

Before long, Don January asked Johnston if he and some other tour players could play and the event gained marquee value. It was played at the Biltmore and Hiwan near Denver and in its final episode, the Broadmoor in Colorado Springs.

The last one was a big success with the media and the public. “I started to plan for the next year and was told Frontier may go bankrupt,” Godbey said. “So that ended the tournament. But it all happened because Bill called the company chairman with his idea.”

One of Johnston’s favorite things was to create a golf event, whether it was for pros or amateurs or members. That’s not a very sexy topic but Johnston is rightfully proud of one of his creations. He started a junior tournament for boys and girls in the Phoenix area in 1962. He asked Arizona Governor Paul Fannin if he could call it the Governors Cup. Fannin not only agreed, but insisted on paying for the annual trophy.

Bill Johnston, a two-time PGA Tour winner, is a member of the Arizona Golf Hall of Fame and Utah Golf Hall of Fame. [Photo: Bill Johnston]

When Fannin moved on to the U.S. Senate in 1965, his successor declined to provide a trophy. So Johnston, slightly miffed, renamed it the Fannin Cup.

That tournament is still operated today by the Thunderbirds, the group that runs the PGA Tour’s Waste Management Phoenix Open. In its 57th year, this junior event is older than most PGA Tour stops.

Contributions like that plus his long-time residence in the Phoenix area and his 23 Phoenix Open appearances helped Johnston finally get inducted into the Arizona Golf Hall of Fame last year. He’d been in the Utah Golf Hall of Fame for 25 years.

Godbey once asked Johnston why he wasn’t in the Arizona Hall and the old pro answered with a smile, “I made lots of people uncomfortable.” When Johnston’s election was announced, Godbey asked what happened to all those people he’d made so uncomfortable?

“I outlasted them all,” Johnston said with a wider smile.

He’s still going strong at 94 and enjoys old-school values. He does email only grudgingly. He prefers handwriting on paper. Which is why I got a note in the U.S. Mail, written with beautiful penmanship, thanking me for meeting with him before I even started writing this story or before he knew I was going to write about him. The note was courtesy. Old school.

Back at The Adobe, he insists before we start our chat that I order a late breakfast. While I devour an all-world Spanish omelet, he barely nibbles on a piece of toast, all he ordered. I try to get him to take a break and eat the toast — at 94 just like at 18, he’s kind of scrawny. He admits he had breakfast earlier with friends but ordered something so I wouldn’t feel awkward as the only one with food.

It’s early afternoon and beautiful as only Phoenix is in February. Johnston picks up the tab. Apparently, he arranged earlier for the waitress to deliver it to him. Despite my stringent objections, he won’t let me pay. What am I going to do? Wrestle a 94-year-old for the bill? Plus, I’m not positive I can take him. So I give in.

It’s been a wonderful life for Johnson. The grandchildren and great-grandchildren count stands at 16, Johnston says, and another is on the way. He returned to Provo last year when his sister died at 91. While celebrating her life, he spent a few days with great-grandkids who were 6, 4, 2, and 1.

“Were they able to keep up with you?” I asked.

He laughs and says, “I had a ball.”

Two years ago, JoAnne passed away at 87 after a long battle with Parkinson’s Disease. Her last seven years were an ordeal. She couldn’t take care of herself anymore. So Johnston did. He promised her he’d never put her in a rest home. And he never did.

“She wanted to die in the same house she’d lived in for the last twenty-some years,” Johnston says, “and that’s where she died. She was such an amazing woman.”

In war or in love, it’s all the same. You’ve got to be lucky.

Johnston was.

He is.

Gary Van Sickle has covered golf since 1980 for Sports Illustrated and Golf.com, Golf World and The Milwaukee Journal.

Email:gvansick@aol.com

Twitter:@GaryVanSickle