In LPGA's infancy, 'Mr. Golf' excels as ladies' man

The LPGA kicks off its schedule this week, in Florida, same month, same state as the tour did 70 years ago in what is regarded as its first official event. The Tampa Open was played Jan. 19-22, 1950 at Palma Ceia Golf & Country Club, where the great Walter Hagen won his last individual title on the men’s pro tour 15 years earlier.

It was fitting that an amateur, Polly Riley, won that inaugural event, because professionals comprised only a small fraction of the field. Thirteen pros would sign the charter for the new organization later that year, becoming “The Founders,” golfers rightly credited with charting a new – and what turned out to be enduring – course for females in the sport. They governed as well as competed, administrators and entertainers, immersed in the details of their new frontier.

In the LPGA’s infancy, though, one man played an influential but sometimes underappreciated role.

Installed as LPGA tournament director, Fred Corcoran provided what the short-lived WPGA (Women’s Professional Golf Association), started in 1944 by pro Hope Seignious, had lacked: experience running a golf tour and the connections that came with years on the job.

“I think you have to give a lot of credit to Hope Seignious, and her dad, because they helped us a lot,” Patty Berg told author Rhonda Glenn in The Illustrated History of Women’s Golf. “She had tremendous vision, but I just thought we had to get going, that’s all. We had to get somebody with Fred’s background.”

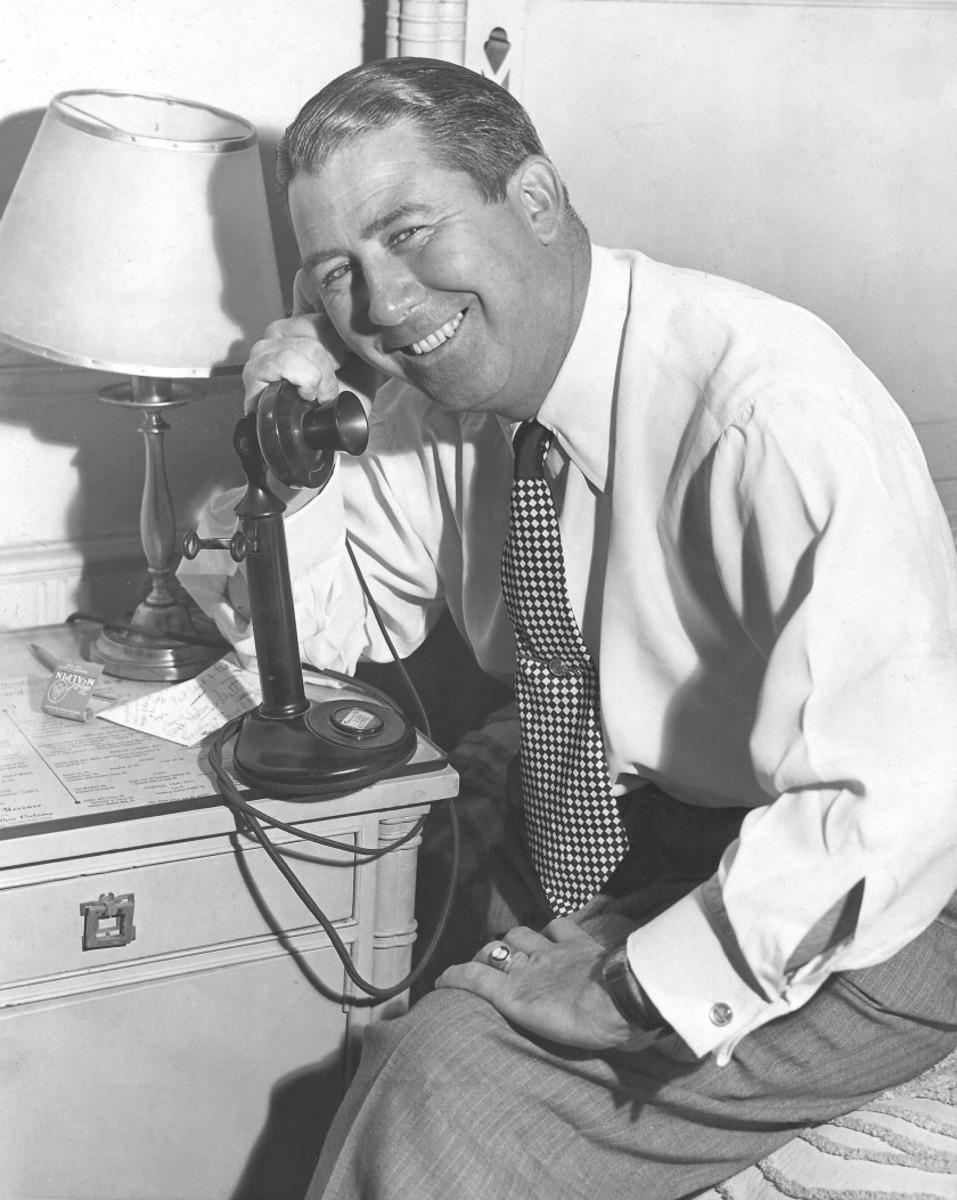

Corcoran had managed, and later promoted, the fledgling PGA schedule in the 1930s and ’40s. He also handled the business affairs of individual athletes: golf’s Sam Snead and Babe Zaharias, baseball’s Ted Williams and Stan Musial. He wasn’t technically a press agent but performed like one, a sportswriter’s best friend during a time when there were a lot of newspapers and plenty of column inches to fill. Corcoran, whose “Mr. Golf” tag made sense, was a deal-maker and storyteller extraordinaire.

“Anyone in the golf community can recall a mental picture of this rotund Irishman with the moon face and Boston accent entertaining friends in Singapore, St. Andrews or Springfield,” John Radosta wrote in The New York Times’ 1977 obituary of Corcoran. “Somehow, it seemed he had no time left for work but, in fact, he worked hard.”

It was L.B. Icely, president of Wilson Sporting Goods, who believed Corcoran could work some magic with a new tour for female golfers. Icely had two of the best, Berg and Zaharias, under endorsement contracts, and with the WPGA sputtering in the late 1940s, he needed a platform for his stars.

Wilson, with other manufacturers chipping in later, paid Corcoran’s salary, and he set out to do his thing. One of the founders, Helen Dettweiler, told Glenn that a women’s pro tour “was awful sick for a while until Fred Corcoran came along. He really got it underway. He was the one who was really instrumental. He did everything.”

Corcoran’s most important success was wooing fashion magnate Alvin Handmacher to pony up significant sponsorship dollars to promote his company’s Weathervane line of women’s clothing. Corcoran pitched the wealthy businessman on a cross-country progressive tournament – four consecutive 36-hole events, with weekly winners and an overall champion for best 144-hole total.

In the spring of 1950, the first Weathervane Transcontinental went from Pebble Beach to Chicago to Cleveland and concluded in New York, with Zaharias winning $5,000 of the $17,000 total prize money for low aggregate score.

“It became the skeleton of the women’s professional tour, to be fleshed out with intermediate stops for other events,” Corcoran’s daughter, Judy, wrote in her 2010 book, Fred Corcoran: The Man Who Sold the World on Golf. “Fred wouldn’t go so far as to say that without Alvin Handmacher and his Weathervane Championships, there wouldn’t be a women’s pro tour today. But make no mistake about it – Alvin put the Ladies’ PGA in business.”

The big-money competition was held for three more years, with the final edition concluding in 1953 at Whitemarsh Country Club in Philadelphia, where player discontent had made it a tense week. The LPGA would continue without its biggest sponsor and, presently, without Corcoran at the helm as the women took more control of their destiny.

“He understood me, and I understood him,” Corcoran later wrote in Unplayable Lies about his relationship with Handmacher. “Neither of us wholly understood the girls.”

Growing pains were no doubt inevitable, given the enterprise. Though brief, Corcoran’s LPGA stint helped give the LPGA traction for the long road ahead.