At Bay Hill, it’s as if Arnie never left

ORLANDO, Fla. – At the Bay Hill Club and Lodge, a lovely place Arnold Palmer first stumbled upon amid acres of citrus groves in the 1960s – and before a squeaky, giant Mouse would overtake this town – there’s a whole lot of Arnold Palmer to go around. One hundred and twenty-one players on the grounds this week will divide a purse of $9.3 million, and there are a few icons to thank for that. There’s Jack; there’s Tiger; and of course, there is Arnold, he being the game’s first true superstar of the television era, and whose sweat and leadership moved most of the dirt to eventually pave this lucrative road of gold.

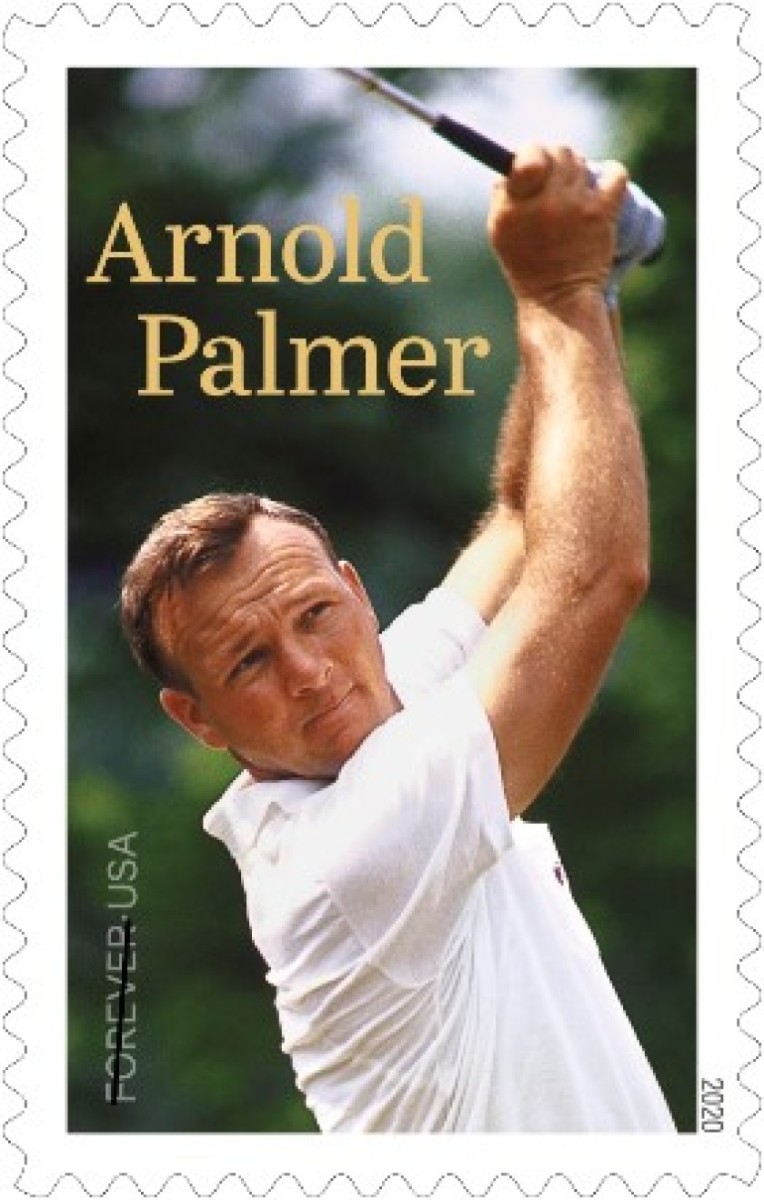

At his namesake tournament, the Arnold Palmer Invitational, Palmer’s Callaway golf bag filled with his Callaway clubs sits beneath a colorful umbrella at the end of the practice grounds. A digital Arnold Palmer Invitational leaderboard sits just right of the tee. Across the way, near a viewing box next to the ninth green, The Arnold and Winnie Palmer Foundation that benefits two local hospitals is emblazoned across green screening. Between the tee and the practice green is the massive makeshift onsite studio for Golf Channel, the around-the-clock golf network that Palmer was so instrumental in getting off the ground. A short walk away stands a giant merchandise tent where one can purchase just about anything Palmer – bucket hats, ball caps, shirts, balls, towels, markers, pinflags, head covers – name it, and you can buy it. Shoot, on Wednesday, the U.S. Postal Service even unveiled a special stamp honoring the man.

Palmer has been gone since September 2016, and the tournament he loved so much is now managed in great part by Amy Saunders, one of Arnold and Winnie’s two daughters. Palmer’s grandson, Sam Saunders, who is in the field, and Sam’s dad, Roy Saunders, also keep the Palmer flame glowing. There was ample consternation about the tournament’s future in the years following Palmer’s death, but this year’s lineup is stacked, even with eight-time champion Tiger Woods at home in Jupiter.

We live in interesting times. There is a seemingly potent virus leading off our daily morning news, producing considerable fear and panic, and there’s far too much division among Americans over politics. Too many people are red or blue instead of red, white and blue. On the highway of life, there is way too much road rage. And then there is this little sidebar of golf, and a tiny golf tournament in a not very big city, and one man’s giant imprint that remains here even if the man himself no longer does.

Arnold Palmer was a wise man. He once said that if everyone in the world played golf, we would not have wars. He was probably right. He usually was. Wanting to hang on to his kindness and generosity and ideals in these times is not so much a marketing hook for a tournament as it is a throwback call to civility and just plain being nice to one another. Palmer tried to be kind to every person, big or small, who crossed his path. Wouldn’t it be great if, for more than just this week, we all could channel our inner Arnie? It is somewhere deep within all of us, no?

“It’s not even the on-course stuff,” said Australia’s Marc Leishman, the 2017 API champion who is serving as one of three tournament ambassadors this week. “He was one of the most successful players in the history of the game on the golf course, [but] it’s the off-course stuff that inspires me more. If there are some kids who want an autograph, or want a picture, and you’ve had a bad day, I mean, how bad can it be? You’re playing golf for a living, right?

“You go over and do that because you think, well, what would he have done?”

There’s an easy answer. You know exactly what Palmer – who learned his toughness from his pop, Deacon, and his manners from his mother, Doris – would have done. This writer has been covering the PGA Tour stop at Bay Hill since the mid-80s, to the days when Palmer still would step onto the first tee and compete in the event. When he stopped playing, there were four more hours in his day, and he was everywhere. Everywhere.

My wife isn’t much of a golf fan, but she and a friend came to the tournament a few years back when Arnold was in his 80s, and within 20 minutes of reaching the 17th green, they had a keepsake picture alongside Arnold. Doesn’t everybody? Doesn’t every golfer you know have their own Arnold story? That didn’t just happen. He worked at it. He’d sign autographs until his white shirt was covered in black Sharpie marks. He said yes when others would say no. The first year he was gone, the tournament named five folks to be ambassadors, trying to fill Palmer’s giant shoes. The fivesome discovered quickly that they simply couldn’t cover all the ground that Palmer did.

Davis Love III, whose father played the PGA Tour in the 1960s and ‘70s, knew Palmer since the early days when Love’s dad, the late Davis Love Jr., starting taking him to events.

“Ten years old, I knew who Arnold Palmer was, and he knew who I was,” said Love, who has been coming to Bay Hill since 1986. (He was a tournament runner-up three times.) “At the Atlanta Country Club, I always tell people, when they saw Arnold go by the ropes and pat a kid on the head, that was me.”

After Love shot par 72 on Thursday (scores), his caddie was about to set Love’s golf bag next to Palmer’s on the practice tee, but Love didn’t feel quite right about it. He moved down about 8 yards, leaving some room. Brooks Koepka eventually ended up filling that space. Love doesn’t know what to make of this tournament without his old friend here. Weird is a word that he uses a bunch.

“They’re trying to keep the legacy going, and all that makes me feel sad,” Love said. “Do we have to? I mean, are we really ever going to forget? It’s really a great question. It’s a weird feeling.”

But advancing the legacy of Palmer is important to the younger generation that now fills the tournament’s tee sheet. Surely all the young players know who Arnold Palmer was, and might know the many tournaments he won, but do they really fully understand the man’s impact not just on golf, but on life, and on all those lives he touched?

Two years ago, as an amateur, Collin Morikawa was selected among all Palmer Cup participants as the player to represent the group at the API. Morikawa was 21, an amateur, still a student at Cal, and the API was just his second PGA Tour start. His visited Palmer’s upstairs office at one point, standing there, taking it all in. The pictures. The books. The keepsakes from his piloting days. His week at Bay Hill had an impact on him.

“I do feel the presence of him,” Morikawa said after his opening-round 70 on Thursday. “This place obviously meant a lot to him, and it means a lot to other people. I think what he represents for the game is pretty special. You kind of want to live that on.”

At Bay Hill, it’s all about trying to be a fraction of the person that Palmer was. Be kind. Be polite. Say hello to a stranger. Deliver a firm handshake and look someone in the eye. Hold open a door. And remove one’s cap when entering the dining area. (“That’s something I really like,” said World No. 1 Rory McIlroy, smiling. “Eating breakfast this morning, I saw a couple of people who were asked to take their hat off as they walked in. That’s nice.”)

Love finds himself signing autographs much more neatly when he is on the grounds at Bay Hill. Palmer was a real stickler for that. Why take the time to sign if somebody cannot recognize your name? A youngster handed Love a flag, and he thought to himself, This is important. Don’t scribble!

“He still has a lot of influence on us in a lot of ways,” Love said of Palmer, “which is very cool.”

Very cool, indeed. May we all find a way to channel our inner Arnie. This is one week, surrounded by memories of Arnold, that it is not very difficult to do. It’s those other 51 that need a little more attention.

Sign up to receive the Morning Read newsletter, along with Where To Golf Next and The Equipment Insider.