If This Was the Year of LIV Golf, Then Let’s Talk About What That Actually Means

As 2022 winds down, Sports Illustrated is looking back at the themes and teams, story lines and through lines that shaped the year. Editor Chris Almeida tracked the drama between the PGA Tour and LIV Golf all year.

Up all night to get lucky

The music is always pulsing. It is not loud, exactly, but it’s got enough oomph to be noticed. Wait long enough and you might forget it’s there, the way your brain eventually dulls a rotten smell. But that’s fine. The music doesn’t actually need to be pleasant or additive. It exists to exist, whether anybody actually enjoys it.

When you’re part of the whole thing, playing in earshot of The Music, you can’t say you’re there for the money. Not exactly. You can’t say you’re there for revenge, either. It has to be about something else. For the team camaraderie. Or—ahem—to grow the game of golf. But occasionally the spokesman will slip up. They will lose their patience and lash out and say something about the money. Or they will show that this is a little about revenge now, even if it wasn’t early on.

Here’s what they can and do say: It’s about golf’s current power structure. It’s about a sport that is mostly plodding and forgettable. Golf was boring for so long, and then for some time, starting 25 years ago, it was cool. Now, things are starting to get boring again. That’s what The Music is about, ostensibly. Fixing the boring of it all.

But if LIV Golf existed solely to make golf better, it would be pretty boring, too. Once you love the game, it will render you unable to think about much else. But if you don’t love golf? Well, who could blame you? It’s expensive and slow and difficult in a uniquely frustrating way. And LIV isn’t interested in changing any of that. Play all the music you’d like. Golf is still going to look like golf. If LIV was looking to change the sport at its core, it wouldn’t be the XFL to the PGA Tour’s NFL. It would be Holey Moley.

But LIV is not about revolutionizing a sport. It’s about something else. Yes, it’s about sportswashing and some form of reputation laundering or tourism advertising for Saudi Arabia’s government. But, really, its purpose is bigger (or smaller?) still. It’s just part of an international pissing contest. This is really just a story about egos.

All according to plan

LIV Golf is in a world of its own in terms of the scale of its project. Rich individuals and sovereign wealth funds have scooped up sports franchises in the past. They’ve funded sporting events. But they’ve always just taken a bite, a piece. It sure seems that LIV wants the whole thing.

For years there have been rumors about entities looking to disrupt the PGA Tour. Which is understandable. Nearly everyone besides commissioner Jay Monahan has grumbled about the world’s most prominent golf governing body. The product hasn’t done much to attract new fans. Aggressive commercial loads; soft, predictable courses; 72-hole stroke-play events nearly every week of the year, seldom featuring all of, or even most of, the world’s top talent—it can all make the Tour feel fairly stale, unless it’s the week of the Genesis Invitational or the Memorial or the Canadian Open. Most players resent the lack of guaranteed money and the purses that don’t increase quite as quickly as the revenue does. A smaller set resents the way the Tour buoys anonymous golfers instead of feeding the lion’s share of payouts to stars.

Seeing this vulnerability, moneyed interests have flocked to golf, some trying to partner with the Tour and revamp its product, others trying to destroy it entirely. The leaders of the latter group, the Saudis, were the first to market. Eight three-day, 54-hole events across the world, with no cuts. Forty-eight-man fields, split into 12 teams. Massive purses, with even bigger gobs of money for up-front player guarantees.

LIV’s CEO and commissioner, Greg Norman, has suggested that Tiger Woods was offered more than $700 million to join the upstart league. Whispers have put the numbers for Rory McIlroy, Jon Rahm and Hideki Matsuyama around $400 million. Of the players who actually jumped ship, signing bonuses have ranged from roughly $200 million, for Phil Mickelson, to seven-figure deals for a slew of newcomers, like James Piot, the 2021 U.S. Amateur champion. In other sports, paying rookies a couple of million dollars is standard; but in golf, such up-front payments were previously unheard of.

Why overpay everybody, not just the stars, when (generously) four active golfers are household names, and even most U.S. Amateur champs will struggle to squeak out a few million bucks as a professional? Well, here we go:

LIV Golf serves different purposes for different people, but for its backers it serves just one: to soften Saudi Arabia’s public image. That was made clear months ago. The first mainstream splash LIV made wasn’t about revolutionizing golf; it came in February with the publishing of Phil Mickelson’s comments to author and former Sports Illustrated writer Alan Shipnuck about the Saudis’ being “scary motherf-----s” who “execute people over there for being gay” (but whose money, it seems, nevertheless made them worth dealing with). Mickelson was almost immediately dropped by all of his sponsors, and LIV briefly looked to be on the ropes. Mickelson’s comments became news, not just on ESPN but on CNN as well. Sportswashing, suddenly, was talked about with as much urgency as sports gambling.

But LIV, obviously, recovered and played its inaugural season, beginning in June. The league did not get a TV contract or any sponsors willing to buy ads, but on YouTube LIV at least went through the motions. And now? News about the competitions themselves, or about the surrounding feuds, has buried any concerns about Saudi Arabia, whose money is keeping the whole thing afloat. At this point, calling LIV sportswashing feels like something done only by people late to the news.

Well, we’re reflecting at the end of the year, so please grant me the exception: It remains relevant as ever that this is sportswashing. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler, knows that the Kingdom will eventually exist in a world where its oil reserves alone cannot sustain it, so he and his advisers have looked to diversify, preparing for a post-petrostate future. The $620-billion Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF) has purchased stakes in Uber, Facebook and Disney. It brought boxing, pro wrestling and Formula One events to the country. When the PIF bought a majority stake in Newcastle United last year, human rights groups and Premier League clubs alike condemned the takeover. But now Newcastle is in the second spot on the EPL table, just ahead of Manchester City and Tottenham Hotspur. The protests have subsided. There is nothing left but a team headed for the Champions League.

Every time a new sportswashing project pops up, life goes on. There’s a wave of resistance, then some awkwardness … and then Anthony Joshua and Andy Ruiz are battering each other under the lights on the outskirts of Riyadh—or is it Germany, or Las Vegas. Ah, who cares.

More recently, some coverage of LIV—the coverage that has bothered to engage with the overarching vision behind it—has projected skepticism that the new tour is, in fact, a traditional sportswashing endeavor. Zach Helfand writes in The New Yorker: “One person who has been in contact with [Mohammed bin Salman] said that the crown prince has given up on trying to fix his reputation in the West. ‘He’s not that naïve,’ the person said. After LIV’s launch, Jamal Khashoggi and Sept. 11 have been talked about more, not less. [David Schenker, a former Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs] believes that establishing Saudi Arabia as a golf destination is LIV’s main aim.” (It’s worth noting here that Saudi Arabia currently has just eight courses, only one of which—Royal Greens—could be considered any kind of destination.)

And David Roth writes in Defector: “It seems more correct, at this point, to read LIV not as some usurious attempt by the kingdom’s rulers to buy themselves out of some obscurity or shame, but as something more triumphal: as proof that none of that matters, because of how powerful their money makes them. LIV’s very existence is a taunt.”

Both theories could be correct. Incremental, realistic, concrete gains can come alongside the visceral thrills of bluster and petty wins. LIV, as a political play, can be both effective and pathetic. But that debate is a level removed from most of the conversation about LIV—about whether it will be granted Official World Golf Ranking points, or whether its players will participate in next year’s Ryder Cup. (This week it was announced, as expected, that LIV golfers would be allowed to play the Masters.)

That’s how you know that the sportswashing is working.

The face

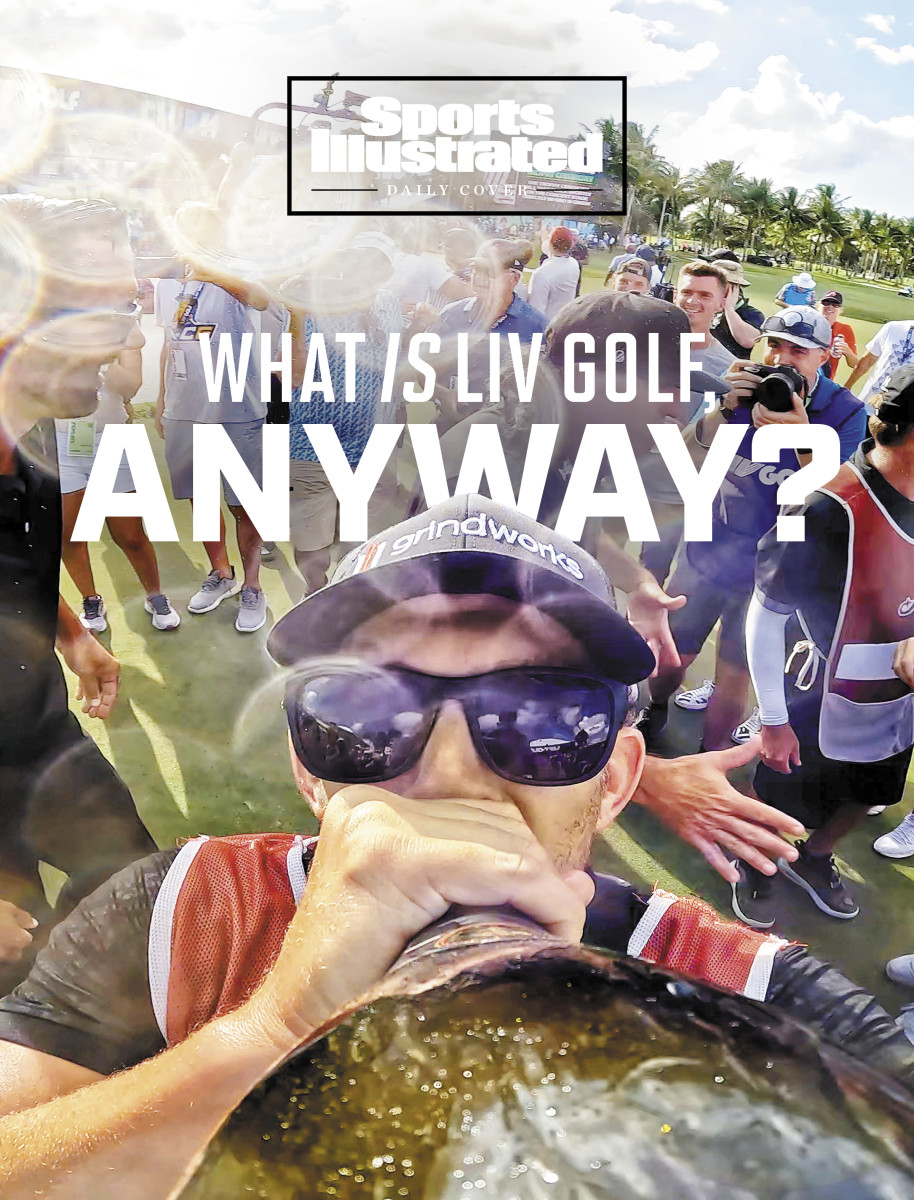

Let’s talk about the pictures.

They both feature Greg Norman. In the first, posted on Instagram in October 2020, Norman is captured walking along a beach. Shirtless, he looks incredible for a man of any age, much less one in his mid 60s. The caption: “A man and his dog on a Sunday.” Below his chiseled torso, through his swim trunks, one can very clearly see the outline of his genitals. It does not seem that this was a mistake. Less than a year later, Norman posted another photo, again on Instagram, this time to commemorate the sale of his Florida estate, named Tranquility. And in the frame: Norman, mid-shower, turned away from the camera, his bare ass visible through steamed glass. Here is a guy who likes to be seen. (Disclosure: The rights to Norman’s image are managed by Authentic Brands Group, which owns Sports Illustrated.)

With regard to his role as LIV Golf’s first commissioner, this seems to be a feature, not a bug. Norman is a rich man, and that’s largely because of his ability to leverage his brand in markets from wine to clothing to golf courses. But in those ventures and this one there is something shared: an ability and willingness to make noise. Here is a man who, during his playing days, would arrive at tournaments in a helicopter. He owned so many Ferraris that he lost track of exactly how many were in his possession.

Say what you want about Norman, but it would be hard to deny that he has a knack for branding. For years, he cared about promoting himself—and occasionally that obsession would also help out those in his orbit.

One such promotion: In 1994, Norman pitched something that might sound a little familiar, a tour featuring events across the world, with 30-player fields and huge guarantees and payouts. He’d secured a broadcast deal with Fox. It was to be called the World Golf Tour.

After getting wind of that idea, however, Tim Finchem, then the PGA Tour’s commissioner, also did something that sounds a little familiar: He threatened punishments and lawsuits and made Tour members bend the knee. (In 1999 he launched the World Golf Championships, a collection of higher-paying, no-cut events. Unfortunately, they looked a lot like the regular PGA Tour events that occur nearly every week of the year. Today only one remains, and it’s a match-play event.)

Norman, though, is not one to let go of his grudges. Earlier this year, The Washington Post’s Kent Babb painted a picture of a man who structured his career, and perhaps his whole life, in defiance of his father. Merv Norman was cheap, so Greg had a plane and a yacht and all those Ferraris. Merv said golf wasn’t a job, so Greg slammed him against the refrigerator and told him "f--- you" and held on to the incident for decades. And then he openly fantasized (to SI) at the Masters in 1996 about getting a hug from his dad.

And so here we are, in 2022, watching Norman work out his tortured relationship with the PGA Tour, trying desperately to slam it against the fridge and also to get it to hug him. The PIF’s near-bottomless reserves will ensure that this time Norman will not fail, at least not at the first part.

Which is not to say that Norman has been a tactical or shrewd operator. In May, when asked about Saudi Arabia’s abysmal human rights record, Norman responded, in part: “We’ve all made mistakes.” When asked about the Kingdom’s execution of 81 political dissidents, he said, “I’m not going to get into the quagmire of whatever else happens in someone else’s world.”

All of those comments, though, have receded as Norman has just … continued to talk. In February, after the PGA Tour announced that any player who joined LIV would receive a lifetime ban, Norman wrote a melodramatic open letter to Monahan that began, “Surely you jest,” then suggested that the Players Championship be called “The Administration’s Championship.” Then signed off like some moody tween writing fan fiction: “This is just the beginning. It certainly is not the end.”

It’s all gotten a bit awkward. McIlroy said in November that for any detente between the PGA Tour and LIV to exist “Greg needs to go. … No one is going to talk unless there’s an adult in the room that can actually try to mend fences.” Woods reiterated the same idea, nearly verbatim, weeks later.

It’s not exactly new for Norman to take his licks publicly. Though a prolific winner as a player, he became just as well known for his feuds (with Woods, and even Jack Nicklaus, who was once a good friend), his messy divorces (he began an affair with Chris Evert while she was married to one of his closest friends, divorced his first wife, married Evert and got divorced again, all in the span of two years) and, most of all, his collapses. He won just one major in 1986 despite leading all four tournaments going into Sunday. At the ’87 Masters he lost in a playoff when Larry Mize chipped in from nearly 50 yards out. And when ESPN aired a 30 for 30 documentary about Norman earlier this year, it centered not on his years atop the rankings, but on the most infamous collapse in golf history: his loss of a six-shot Sunday lead at the ’96 Masters.

With his cultivated air of luxury and his not-so-private affairs, Norman might fancy himself a JFK, but he’s more Richard Nixon—an obsessive and vindictive man with some big wins, and some even bigger self-inflicted losses. He is, to many, a cringeworthy figure. It’s hard to watch him go about his business, knowing everything we know about him. As the writer Garry Wills once wrote about Nixon: “One is embarrassed to keep meeting the dog one kicked yesterday.”

Still, though loud and provocative and often unconsidered, Norman is serving his role. He is a big name, and he creates headlines. He floods the zone with s---. He is very good at being seen.

And so, while LIV may eventually want a quieter face, Norman’s modus operandi has been perfect for, at least, the opening act. It was always going to be impossible to square the circle of what is happening. LIV didn’t need somebody who could justify its existence. It needed somebody who could create so much controversy that its original sins would drift off into nothingness. Sportswashing does not work by saying that it is sportswashing. It works by saying anything—everything—else.

Isn’t Saudi Arabia one of the least-free countries in the world?

What? Didn’t you all get over that months ago? We’re here to talk about how much the caddies are getting paid. About the PGA Tour’s operating as a monopoly. About the rights of independent contractors. We’re here to grow the game. And what about Jay Monahan’s private jet? Anyway, if that all makes you bored or upset, check out this golf course in Jeddah. Brooks Koepka got his career back on track there. Maybe, one day, you can tee off there, too. … Sorry, what was the question?

Sore winners

On the last day of 2019, B.D. McClay at The Outline pronounced the ’10s to be the Decade of Sore Winners: “New York Times columnists and billionaires who think their critics are symptomatic of a second Holocaust? Sore winners. Conservative pundits who, flush with [Donald] Trump’s favorable court appointments, indulge in ever-escalating paranoia over drag queen story hours are sore winners. Directors of Marvel films who were angry at Martin Scorsese for not loving their work are sore winners. The police are sore winners.”

Above all, though, it was Trump’s decade, and nobody better epitomizes the archetype of the sore winner than the former president. “The sore winner wants acclaim, but not responsibility; respect without disagreement; wealth without scrutiny; power without anyone noticing it’s there,” McClay writes. “It’s a delicate line to walk, but not impossible.”

It makes too much sense that Donald Trump is in bed with LIV. Two of his courses hosted tournaments during the series’ inaugural season, and it seems likely that the crown jewel of his golf empire, Turnberry, where Norman won his first major, will eventually host an event, though it’s not on the LIV schedule for 2023. Also, Trump has his own vendetta against the golf establishment: The PGA of America moved the ’22 PGA Championship from Trump’s Bedminster course to Southern Hills in the aftermath of the Jan. 6 insurrection. That move reportedly upset him on a “different level of magnitude” from his—checks the record—second impeachment. (Nicklaus, himself an unabashed Trump backer, referred to the Bedminster move as “cancel culture.”) So in LIV, a financial boon if nothing else, he has found a way to both make some cash (which it seems he needs at the moment) and get revenge. To win sorely.

In late July, at Bedminster, LIV trotted out what in 2016 would have been considered a star-studded golf field for three shotgun-started rounds, while a de facto MAGA rally occupied the rest of the property. Tucker Carlson and Marjorie Taylor Greene yukked it up in a suite. Trump gave an impromptu speech. (“Well, nobody has gotten to the bottom of 9/11. … But I can tell you that there are a lot of really great people out here today, and we’re going to have a lot of fun!”) According to news reports, only a few thousand fans attended—less than half of what a regular PGA Tour event draws—and tickets were available for just a dollar. But that hardly seemed to matter for those in attendance. They saw what they wanted to see. They also saw 46 year-old Henrik Stenson win a golf tournament.

Before that event, Trump wrote on Truth Social that golfers who stuck with the “very disloyal PGA” would “pay a big price when the inevitable merger with LIV comes.” The former president is not content to see LIV slowly pick off top PGA players. He must taunt them, complain about them, mourn his inability to manifest a total, undeniable victory over them.

Trump, though, has other affairs to occupy his time. Most of LIV’s golfers do not, and many of them have filled their leisure hours with complaints that the world is pitted against them. When Mickelson kicked off the first big LIV news cycle in February, he accused the PGA Tour, hilariously, of being held back by “obnoxious greed.” Koepka, in a press conference in June, lashed out when asked whether he planned to sign with LIV, accusing the media of “throwing a black cloud on the U.S. Open.” (He signed days later.) When a Twitter user with five followers wisecracked about the strength of LIV’s fields, Graeme McDowell took the time to challenge said Twitter user to a match. Lee Westwood and Ian Poulter have picked on people closer to their own size, but generally they have shown a stunning inability to log off. Patrick Reed, himself no stranger to concerning Twitter activity, filed a $750 million defamation lawsuit against Golf Channel and a handful of its employees. (The initial filing was dismissed, but Reed refiled it Dec. 16 while adding more names and raising the price to $820 million. And if you want to get a sense of the tone of the lawsuit, just know that this guy was Reed’s lawyer.) Talor Gooch, comparatively, looked, well, smart when he responded to a question about sportswashing by saying, “I’m a golfer; I’m not that smart. I try to hit a golf ball into a small hole.”

It is natural to look at all these sore winners and wonder why they are acting out. Because people on social media rile you? That’s what the money’s for. But the petulance is the plan. A second tour that merely replicates the PGA Tour would have no reason to exist. An identical tour that pays more money was always going to invite questions about where the money was coming from, and why. The cosmetic tweaks—the shotgun starts, the inscrutable team competitions, The Music—get held up by players and LIV announcers as the reasons for LIV’s existence. But the grievances add an extra layer of justification, of obfuscation.

It’s not really about the big picture anymore. It’s just about winning. Sorely.

An aside

If I had to characterize LIV in a few words, they would be permitted transgression. The league is trying to sell the thrill of being bad while permitting, even encouraging, the Bad Boys to do everything they aren’t supposed to do.

Has LIV really been a tour of defiance? Or has the Saudi money created a little pocket universe where the rules are just a little different? LIV’s slogan, “Golf, but louder,” is meant to signal that this tour is not uncool. That the things about golf that are stodgy and old and dumb and polite are all gone. Here, you’re cracking beers. You’re screaming with the crowd. You’re wearing shorts. You’re just having fun out there with your buddies. And that’s great—the players are, too.

There is one PGA Tour event each year, in Phoenix, that carries the same vibe. It is loud. It’s sweaty and sticky and so booze-soaked that you can smell it through the television. When a golfer makes an ace on the 16th hole, so many fans end up throwing their drinks out onto the course that the round has to be paused while the mess is cleaned up. But that’s it. It’s transgressive because it happens only once a year.

LIV is loud, but only until the signs go up to make sure nobody yells during a player’s backswing. Yes, shorts are allowed, but don’t get any ideas about too many other changes. (Majed Al Sorour, the CEO of Golf Saudi, the organization tasked with growing Saudi Arabia’s domestic golf offerings and its influence in the competitive scene abroad, told The New Yorker of that decision, which was reached by player vote: “Democracy’s O.K. … Sometimes!”) Fans will do what the players want, and players will do what LIV wants. This is not a more-relaxed space, just a golf event with a different code.

The good guys?

The PGA Tour is not the first—or the millionth—place you would point to if you were trying to give an example of a progressive institution. David Duval was once considered the token reader on tour because he loved Atlas Shrugged. (Bizarrely, he was also the Tour’s token Democrat. In A Good Walk Spoiled, John Feinstein reported that the 1993 Ryder Cup team did not want to visit the White House before heading to England, because not a single one of them voted for the unconscionably liberal Bill Clinton.)

Even compared to the most conservative American institutions, elite golf, as a whole, has often stood defiantly in the past. The PGA of America’s infamous Caucasian-only clause stood until 1961. In ’90, Shoal Creek, host of that year’s PGA Championship, accepted its first Black member—and just as an honorary member—only after pressure from sponsors and a turn in public opinion.

Among the three most exclusive clubs in the world today, Augusta National is somehow the most progressive. In the early 1990s, Cypress Point forfeited the ability to host events rather than comply with the PGA Tour’s membership diversity requirements, and never looked back. Until 2021, women weren’t even allowed onto the property at Pine Valley, in New Jersey, except on Sunday afternoons. (On her honeymoon, Barbara Nicklaus was driven around the club’s perimeter as Jack played the course.) If the revolution is televised, it won’t be on PGA Tour Live.

This is all to say that one of LIV’s implicit selling points, that it’s an alternative to The PGA Tour as the Out-of-Control Woke Establishment, is patently absurd on its face. The Tour is a conservative institution in both its politics and its operations. It was a perfect target for LIV, because it moves slowly, when it moves at all.

Scan through LIV’s fields and you’ll notice that only about half the players are familiar to even the truly golf-obsessed. (Among the team rosters, Torque and the Iron Heads are, for my money, the roughest. Take a look.) But if you isolate the best 15 players or so, it becomes clear that LIV has taken its pound of flesh.

Koepka, Reed, Gooch, Bryson DeChambeau, Louis Oosthuizen, Joaquin Niemann, Abraham Ancer, Jason Kokrak, Harold Varner III and Marc Leishman allowed PGA Tour fields to feel well stocked. They are title winners ostensibly in their primes. Few will miss Poulter for reasons other than nostalgia, but those younger players represent a substantial chunk of talent that made the PGA Tour seem like a fully staffed workplace.

Dustin Johnson might have saved the entire LIV enterprise himself, and not just with his play. Perhaps the best golfer of his generation, he jumped before the first LIV event, when the full stink of Mickelson’s comments to Shipnuck were still in the foreground. Johnson created the permission structure for other blue-chippers to defect. For the second event, Koepka and DeChambeau joined; and at the end of the summer, of course, Cam Smith.

Smith was the great coup of Year 1. He won the Tour’s prided Players Championship, played in the final group at the Masters and then chased down McIlroy to win the Open at St. Andrews, rising to No. 2 in the world. He defected just weeks later.

So, what does this have to do with the PGA Tour? Well, everything. Also: It’s complicated. Earlier this year, Monahan drew mockery when he complained he was trying to outduel an entity that wasn’t beholden to traditional market forces. But he wasn’t exactly wrong. LIV may be failing to hit its economic goals, but it’s unclear whether there’s a point at which such bad business will actually cause the Saudis to pull the plug. It is possible (and in my opinion, likely) that even the most competent PGA Tour commissioner would not have been able to conjure the nonmonetary concessions to keep stars while LIV dangled eight- and nine-figure paydays.

Monahan’s Tour, though, has been particularly slow in changing the existing structure of the sport to retain players. A series of “elevated” events was created for 2023—but what does that mean in practice? Just that the prize pools for some existing events will grow. (At $20 million apiece, that’s still not quite as much as the typical LIV event.) The Player Impact Program pool—essentially a bonus—bumped from $40 million to $100 million. And for the first time the Tour will guarantee $500,000 for every exempt player; essentially a salary. The Tour holds up legacy and history as its edge, but it is startlingly clear to nearly everybody else paying attention that golf legacies are built only at the majors, and the PGA Tour doesn’t govern a single one of those. So cut the rhetoric, and get to the heart of it.

Look at what the Tour is really doing, and you’ll see that all it can think to offer is money … which Monahan conceded in the first place was a doomed strategy. Bump the PIP pool up all you want—but remember that Qatar spent $220 billion on this year’s World Cup. You cannot outspend a petrostate.

There are squabbles to be had over how this year has played out. Pundits call weekly for Monahan’s job. The Tour operates as a tax-exempt 501(c)(6) nonprofit, allowing it to eschew taxes but also preventing it from giving preferential treatment to its more famous members or accepting money from private investors. Put aside for a second the absurdity of the Tour contending that it is, first and foremost, a nonprofit; it makes sense to think that the unwinding of the Tour’s nonprofit status, or its existing sponsorships, or the opaque and limiting obligations it currently has, could allow the outfit to combat LIV more effectively. It is also possible that the Tiger-led stars-only meeting in August could allow the stars to more efficiently demand that the Tour meet their needs. The Tour might find more workarounds to funnel money to said stars, like McIlroy and Woods’s virtual golf competition series. It’s possible that there is a way out.

One thing is certain, though: Complacency allowed this all to happen. There might not be a way for the PGA Tour to unify golf now that the toothpaste is out of the tube. But the idea of a Tour revamp did not come out of nowhere. As early as 2019, outsiders were trying to get leadership to consider an alternative system that would allow more money to come into the game. (Rory McIlroy has said he was even approached long before then.) But the Tour’s leaders were too happy with what they’d already created. They didn’t listen.

Rumor has it

LIV’s roster is like a character select screen in Mario Golf where the only choices are Wario, Waluigi and Bowser. Maybe a few Koopa Troopas. No Mario. No Luigi. No Yoshi. Antiheroes and villains are fun when they have somebody to foil—but, put them together, only their devilish selves, and … well, that’s not much fun at all.

Consider a match between two LIV teams, Smash GC and the Majesticks, at the season finale at Doral. Once you get past the team logos, which seem intentionally designed to produce ridicule—Smash GC is represented by an image that can best be described as a cartoon fart—you get to a group of players that perfectly represents LIV’s current coalition.

Smash’s captain, Koepka, is a Bowser if anybody is—all width and arm muscles and steal-your-girl smirks. Three years ago, he was the best player in the world, but injuries turned him into a prime LIV candidate: a big name with four major titles on his Wikipedia page and serious doubts about his game. In October he won the LIV event in Jeddah and talked about how he’d previously believed, briefly, that his career might be over. But now! Well, it’s a whole different story. What’s a U.S. Open win at Shinnecock compared to a trophy at Royal Greens?

Flanking him at Doral were Kokrak, a solid-if-uninteresting Tour pro who proudly sported a Golf Saudi sponsorship on his bag before LIV even had its name; Peter Uihlein, who spent 10 years bouncing in and out of the PGA Tour and who is, perhaps more importantly, the son of Titleist’s former CEO, Wally Uihlein; and Chase Koepka, who never quite got a foothold on the Korn Ferry tour, the PGA Tour’s main feeder. Yes, he is related to Brooks.

The Majesticks are captained by Westwood and backloaded with Poulter and Stenson. (Stenson made headlines when he abandoned his 2023 Ryder Cup captaincy by signing with LIV, but he has mostly kept his mouth shut, at least compared to his teammates. That hasn’t saved him from catching a few strays. “I don’t blame Stenson for going,” Gary Player said in August. “He had no money, so he had to go.”) Sam Horsfield, a former European Tour player, is the team’s fourth member.

Within that group of eight, you can see nearly everything LIV has to offer. Big names here for one last job. Stars with doubts. Awkward favor trades. And … some other guys. Mix in a stilted broadcast product with no real advertisements, and factor in the complete lack of competitive context—how should we think of Brooks’s win in Jeddah? Is it like winning a WGC event? A big PGA Tour event? A little PGA Tour event?—and this is not the most compelling sports product that has ever existed. But it doesn’t need to be. Any sports editor worth their salt knows that the real juice these days isn’t in the games themselves but in the offseason feuds and trades and free-agency rumors. The drama. And there, LIV is king.

The week of the LIV match between Smash GC and the Majesticks, Dustin Johnson’s 4 Aces won that big stack of cash in Doral, and there were two other tournaments of note taking place: the PGA Tour’s rather weak Butterfield Bermuda Championship (won by Seamus Power) and the Portuguese Masters (won by Jordan Smith). But now the rumor mill was churning, too, as it surely will as long as LIV exists. On this occasion it was a report in The Guardian that Xander Schauffele and Patrick Cantlay might be the next big names to defect. (Neither, ultimately, jumped ship, but trying to guess the next defector remains golf’s ultimate parlor game.)

And so the real advantage LIV has—but that it can’t maintain forever—is its ability to stir things up and gesture at a previously unimaginable future. Yes, the courses are stale. The commentary is stilted and sounds like propaganda. (NFL broadcasts are propaganda, too—but at least they do a half-decent job of actually propagandizing.) Yeah, it’s a little weird that it’s all on YouTube. But there might be a day soon when a network picks up LIV and the stumbling course-side reporters are gone and the courses are better and the team logos no longer resemble farts. There might be a day soon when LIV devours the LPGA whole. There might be a day when Norman is replaced by a staid executive. Now, thinking about that tour? Well, that’s not exactly the future I want to live in. But is it interesting? Maybe.

The biggest golf tournament you’ve ever seen

The LIV finale at Trump Doral was pitched as a spectacle. There was a revolutionary new competitive format: match play for the first two days, before a third-day reversion to stroke play. There was the storied course: Doral was a PGA Tour stop and hosted a WGC event as recently as 2016. And, yes, there was a very, very big prize pool: at $50 million, double the haul of the other LIV events. There were even rumors that Trump himself would announce his ’24 presidential campaign at the event. (He did not.)

The whole thing was all tell, no show. The broadcast that felt like state television. The banter about weathermen being wrong. The bizarre slideshows of fans watching from home with their babies. The repeated references to the in-the-future storied history of LIV. (“In years to come, this will be looked back upon as something that changed golf.”) Overall, it was clumsy. Multiple coworkers referred to course-side reporter Su-Ann Heng as “Suzanne,” and she then took the time to correct them on-air. To be fair, the broadcast looked pretty. Had you hit mute, you might not have noticed many blemishes. But with the sound on, every line and interlude landed with the light touch of a World’s Strongest Man competitor.

Mickelson, after being eliminated on Day 1, hopped into the (YouTube) broadcast booth and chatted away. He broke down Smith’s and Johnson’s swings. He rattled off facts about player after player, showing off his deep knowledge of the game, and it was entertaining—a glimpse of the network career he might have enjoyed had he never spoken to Shipnuck. But, at a LIV event, even Mickelson couldn’t keep the shtick going for too long. Once Hennie du Plessis, a 26-year-old South African whose biggest claim to fame is nearly winning the LIV London event, appeared on-screen, Mickelson tapped out. “I don’t know much about Hennie,” he conceded to his boothmates. “Can you fill me in a little bit?”

The third and final day of LIV Doral ended with as good a situation as organizers could have hoped for: Johnson and Smith together on the 18th green, with the possibility that Smith’s team, Punch GC, would snatch the title away from Johnson’s 4 Aces. DJ held his nerve, though, and he locked up the $16 million, to be split between himself, Reed, Gooch and Pat Perez.

Later, at the trophy ceremony, the 12 members representing the three highest-finishing teams stood on a stage with giant champagne bottles. Norman, Al Sorour and Eric Trump looked on, just feet away. A LIV emcee sauntered to the center of the platform, notecards in hand, ready to wrap things up. But Smith had already popped his bottle.

“Before you pop the champagne,” the emcee began awkwardly. Pop! Reed shot his cork, too. “You know what, we had a whole program but ...” Pop! Johnson started spraying. “We do things differently here! Let’s go! 4 Aces GC!”

The Music was back now. The emcee’s mike cut out … and then came on again. Was this all an exciting derailing of the plan? A spontaneous party? Or was the scrapping of the plan just … the plan? Some more transgression, sure to get nobody in trouble.

“This,” the emcee made sure to say before finally ceding the space, “is golf, but louder!”