A Masters Family: North Carolina's Whitfields and a Half-Century of Stories

The legend of Buddy Whitfield and his half century-plus of Masters Tournament ticket lore was cultivated at a long-ago shuttered country ham establishment in central North Carolina. “MIRO County Hams” read the marquee, topped by smaller lettering, “Hot Ham Biscuits, Souvenirs, Coca-Cola.”

Located on U.S. 1 in Sanford, North Carolina, the eatery was the stereotypical hole in the wall frequented by locals, golfers going to and from nearby Pinehurst and other passersby who got wind of the eclectic offerings.

The highly touted biscuits were served in a brown paper bag with ever-widening grease spots and sheathed in a waxy paper, suitable for a quick takeout. Placed throughout the establishment were trinkets you might often find at an interstate all-in-one such as Stuckey’s. The feature attraction was an old tree cut down for placement as the store’s centerpiece to hang all sizes of country hams, fresh out of the smokehouse, ready for at least a full week’s worth of meals and the source of the overwhelming fragrance. If the biscuits were this tasty, then surely the full hams would magnify the biscuits’ scrumptiousness.

The experience was enriched by MIRO proprietor Ed Duffell, the possessor of a bellowing Southern voice and flamboyant personality to pair with his Vitalis-laden dark hair, black horned-rim glasses and red-eye gravy-stained white apron.

“Welcome. Welcome,” he would greet any customer, pause and offer a verbal joust: “Y’all got any muh-nee?”

Whitfield referred to Duffell simply as “MIRO,” and he was the perfect complement to Whitfield's similarly gregarious manner with sayings such as, “Come forward with it,” to get the truth out of somebody or “How is it this time?” to learn the latest scoop.

From this setting, Whitfield formulated that such extraordinary eating would surely be worth a princely sum just one hour into the carful’s southern spring journey. Why not fork over $25 each for the robust hams? There was plenty of room in the trunk of his white Mercury Marquis.

The ham biscuits filled the bellies of Whitfield and wife Doris, three children, Ralph III, David and Jan, and any other tag-alongs such as frequent guest David Chapman. The 300-mile, five-hour car ride southbound from their home in Durham, North Carolina, to Augusta, Georgia, on two-lane U.S. 1 wandered through small towns that made a 1970s day trip both excruciating and adventurous. Sanford, Aberdeen, Hamlet in North Carolina, Cheraw, McBee and Camden in South Carolina rushed by amidst the Sandhills region’s scrub-pine forest and white sandy soil. In central South Carolina, merge onto new-fangled Interstate 20 east of Columbia, just more than 100 miles northeast of Augusta.

Finally, arrive in Augusta, pay to park along the main thoroughfare, Washington Road, just across from the Augusta National Golf Club, pop open the trunk and work the crowd. As a real estate professional, Whitfield knew the drill. Talk golf. What do you do for a living? How are the flowers this year? How about my kids here coming to see the golf … but we don’t have enough tickets. Got any duckets? I’ve got a fresh country ham for you to enjoy if you will let me use your extra tickets for the day. Smiles all around. Sold.

“I’d get two or three fresh, North Carolina hams from MIRO and put them in the car trunk,” Whitfield recounted 25 years ago. “Where could they find a ham like that in Augusta at Masters time? How could they turn that down? That never failed to get me in."

The Masters Ticket

The Whitfields’ efforts to attend the Masters mirrors the entire Masters fan timeline, extending back to the 1930s. Tripping to Augusta is slated to continue in full for an 86th time following the oddity of a November 2020 Masters, delayed because of the coronavirus pandemic but with no fans allowed for the first time, and in April 2021 with but only a few more allowed. The roars will be back in full throat, bleachers back in place and so will longtime visitors and those who have yet to see the place.

Before his death from cancer at age 79 in August 2010, Whitfield attended 56 consecutive Masters, starting in 1955. His middle child, David, now an Atlanta realtor and former college and professional golfer, first came as a 9-year-old in 1969 and will celebrate a year’s worth of Masters visits in April – that is, 52 weeks in a row, with an asterisk after missing the last two closed-door sessions. That’s way more than a century in Augusta between all the Whitfields, most of whom have attended more sporadically.

For much of that time, Buddy Whitfield has been a guiding spirit for the unwashed — his children’s friends, golfers from regular games at Durham’s Croasdaile Country Club and business associates, with most of them making an infant journey. That’s where he earned the nickname Top, as in Top Dog. I was one of those newbies as a sportswriter for the Durham (North Carolina) Morning Herald in 1985, a Durham public course golfer who wrote about the tournament but also followed Whitfield around in my first foray south.

He knew the best places to eat (Luigi’s, French Market Grille and Edmunds Bar-B-Que were favorites), park and spectate. The Tree, a sprawling 160-year-old live oak on the back lawn of the Augusta National clubhouse, remains the rendezvous point if the group is separated — a Boy Scout-like agreement since no cell phones are allowed on the grounds. The hill behind the seventh green was another favorite locale that offered a vantage point for Nos. 2, 3, 7 and 8, with a double-sided manual scoreboard just above. Nearby is a concession stand with the coldest beer, pimento cheese and egg salad sandwiches. A bank of old-school green pay phones allow for business or casual calls outside.

“It’s kind of like Moses going to the Promised Land for us; we always say we’re going to the Promised Land every spring and he led us," said David Whitfield, 62. “I can’t wait to see people I haven’t seen since last year and the place is so beautiful and welcoming."

This was the intent when the Augusta National Golf Club opened in 1932. Co-founders Bobby Jones and Clifford Roberts organized an invitational golf tournament to draw much-needed revenue and exposure for the club. They recruited regionally supportive fans — patrons as they’re officially called by club officials — in advance of the first Augusta National Invitation in 1934, the name used until Masters became official in 1939. The Augusta region’s small population of less than 100,000 in the 1930s couldn’t fully support the numbers needed to make the tournament a success so they spread the word regionally and then focused on folks who wintered in Florida and may be driving back north in the spring.

The public response was good for the Depression-era South, but tickets were still plentiful. Through the 1960s, pop-up ticket stands appeared on downtown Augusta street corners and businesses readily publicized ticket availability in the weeks leading up the usual dates of the first full week of April. Augusta banks had an ample supply of tickets and would often barter a customer’s potential five-figure loan against a pledge for that person to purchase 50 or more badges, which totaled $400-$500.

Business relationships also thrived. H.W. McCullough was a vice president with Colonial Stores, a prominent Southeastern grocer, in Columbia, South Carolina, one hour north of Augusta. Two of his biggest clients were Augustans, barbecue king Clem Castleberry of Castleberry Foods and baking icon Johnny Murray of Murray Cookies, and both were members of Augusta National.

As grocery executives were wont to do, the McCulloughs moved around the Southeast to tidy up business. A move to Durham in the 1940s settled them two doors down from the Whitfields on Watts Street. That’s where teen-aged Buddy and Doris, the McCullough’s daughter, attended centrally located Durham High School and Duke University and married in 1956. Whitfield developed a passion for golf by playing locally.

When his future father-in-law invited the Whitfields to attend the 1955 Masters, it created a passion that never subsided. McCullough wasn’t a die-hard golfer, but through his association with Castleberry and Murray, he had access.

“One year in the late 1950s, I had 19 tickets in my pockets,” said Buddy Whitfield, a 1955 Duke graduate. “There was nobody to give them to even though we tried.

“All those flowers really startled me — the azaleas, the camelias, the dogwoods. Once you go, you get addicted. And then I started taking my children. It was like Christmas for us, four or five of us going to Augusta every year.”

It was during this time that the Masters was also growing up from its trying financial infancy. The same year that Whitfield first came to Augusta was also the debut of a former Wake Forest man, Arnold Palmer, who towed a 26-foot trailer into the outskirts of Augusta for his first start. Palmer was bound to set the world on fire with his good looks, aggressive play and dramatic finishes, as he captured Masters wins in 1958, 1960, 1962 and 1964. In 1956, CBS offered the first live television coverage and added the first color broadcast in 1966. The tournament first sold out in 1967, the patrons list was closed in 1972 and a waiting list was deemed full in 1978.

Fortunately, Whitfield didn’t take his father-in-law’s advice that the ticket spigot would flow on. He put his name and his mother-in-law, Eva McCullough, on the waiting list in 1974, two years after it opened. Good timing. McCullough retired from Colonial Stores and lost his member contacts who were getting older as their businesses drew considerable international corporate interest. The Masters tickets were no longer plentiful.

Good Realtor Training

This is when the Whitfield epic really started. The country hams are just a part of the story for how attached to the Masters — and successful — Whitfield was in his mission. Nothing illegal ever occurred and no one got duped, as often happens when ticket brokers or scalpers get involved with heavy cash infusions at popular sporting events. That characteristic has especially been true at the Masters, where corporate tickets and accommodations packages rise into five figures and are called the “13th month” of income by locals.

David Whitfield said they have never paid more than face value for a ticket and always gained entry, using a great variety of cajoling to obtain tickets. This has been just good, old-fashioned business instinct and personality, the work of two real estate salesmen in the footsteps of Buddy’s father, Ralph “Chop Chop” Whitfield Sr., who was a traveling cigar and candy salesman in North Carolina. And some good luck didn’t hurt.

Buddy Whitfield would peruse the parking areas that encompassed a tournament-run lot, churches, fast-food restaurants, gas stations, small businesses and 1950s-era homes and monitor the flow of pedestrian traffic to and from the Augusta National gates. People departing the grounds at midday would sometimes give up their tickets for the afternoon.

“I told the folks at Southland Associates Realtors in Durham one time that if you want to find a really good realtor, just send him to Augusta and see if he can get a ticket,” Buddy Whitfield said. “Hire him on the spot if he can get a ticket there.”

In asking many passing cars if they had spares, Whitfield noticed one year that an incoming driver was shying away from eye contact.

“I can tell you’ve probably got a ticket or two that you don’t need,” Whitfield pointed to the driver, after a brief introduction, as he settled to a stop that early morning.

Indeed, they had extra tickets, formally called a Series Badge by Augusta National. However, there are deterrents for one-to-one sales since the original holder is held responsible for the actions of the person wearing the ticket. Any wrongdoing such as selling to brokers, for a profit or improper behavior — including getting caught on the grounds with a cell phone — could result in the permanent loss of the ticket. Also, one ticket, not four separate tickets, covers all tournament days, Thursday through Sunday. That makes it imperative for the ticket to be returned at day’s end. This is a big reason the Masters has been called the toughest ticket in sports.

“I will give you the cost of the tickets, a credit card and my driver’s license,” Whitfield began in his discussion with the driver, “and meet you at whatever time this afternoon to return the tickets. We just want to enjoy the tournament.”

At the agreed-upon time of 6 p.m., Whitfield was back at their car to exchange two tickets for his belongings.

“That man was a Baptist minister,” Whitfield said. “I think he was astounded that someone would be true to his word. He probably thought he’d never see me again. When he was leaving, he said he was going to preach his Sunday sermon about me. The topic: Honesty.”

Letters to Augusta

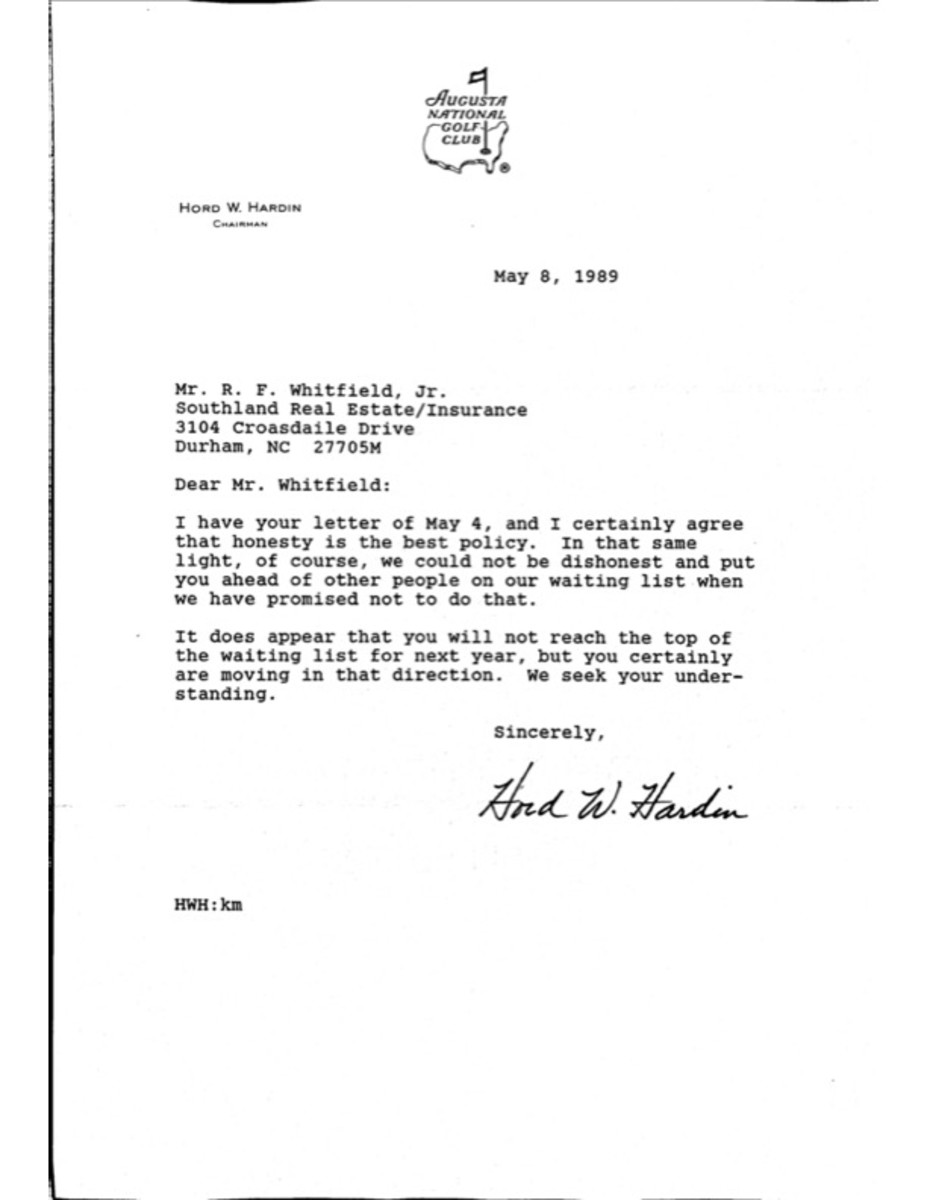

Whitfield's integrity was evident in his assortment of letters to Augusta National, penned on company stationery. For 20 years, he would write for tickets, knowing his name was already on the waiting list, but “just to let them know I was still alive.” Some ticket holders pass away. Others commit a breach of tournament rules. He always received a polite reply from Augusta National, indicating not this year. “If you keep a file on people like me, my file must be an inch thick,” he wrote in 1981.

In 1989, the letter writing took a different turn. During a practice round he attended that year, Whitefield was walking through a parking lot when he nearly stepped on a Radio and TV media credential belonging to Australian Mike Greenwood. The second paragraph of a May 4, 1989, letter to Augusta National Chairman Hord Hardin read:

“Since I have been trying to get on your mailing list for many years without success, I became ecstatic! Truly ecstatic! This, I thought to myself, will be my great chance! Wouldn’t it be wonderful to have a ticket that would get me in the clubhouse, press headquarters, pro shop, etc. Mr. Hardin, you would not believe how excited I became.

“Now the bad news. My conscience would not let me keep the ticket ...”

Whitfield explained that he walked to the TV compound, located on the far side of the Par 3 Course, and returned the credential to a much-surprised Australian TV crew. Then the kicker paragraph in Whitfield correspondence:

“You are probably wondering by now why I have written you this lengthy letter. Well, I’m hoping that since ‘honesty’ prevailed, you might see fit to add my name to your list for tickets in 1990.”

Four days later, on May 8, Hardin responded in a letter: “… I certainly agree that honesty is the best policy. In that same light, of course, we could not be dishonest and put your name ahead of other people on our waiting list when we have promised not to do that. … We seek your understanding.”

Yes, Whitfield understood, with great respect.

“Augusta National doesn’t do anybody any favors,” he said. “They don’t give anybody slack. Whether you’re worth $10 million or $100, you get food out of the same spoon there.”

Reserved Parking

By the early 1970s, Whitfield told his father-in-law it was probably time to park their car elsewhere. They were parking for free in the Augusta National lot, where the current Tournament Practice Facility is located, and it filled up quickly. But every afternoon there was a traffic jam departing the grounds, so they sought paid locations on the opposite side of Washington Road.

That switch became quite fortunate in 1980, striking gold in the yard of Mary Ella Marshall on Azalea Drive, just across Washington Road and less than 1,000 yards from the entrance to Augusta National. A mammoth Masters corporate hospitality company’s headquarters (not affiliated with Augusta National) stands there now.

Through conversation with Marshall, Whitfield learned that she had tickets and wasn’t interested in fighting the crowds. By 1981, she was selling the Whitfields her tickets and Buddy brought or mailed Mrs. Marshall country hams, shipments of Harry and David’s fruits of the month and birthday or Christmas cards for more than two decades. Another parking lot leasee from Pennsylvania, George Burnwood, struck up an annual friendship with the Whitfields and years later when he was too old to attend, he too sold the Whitfields his tickets.

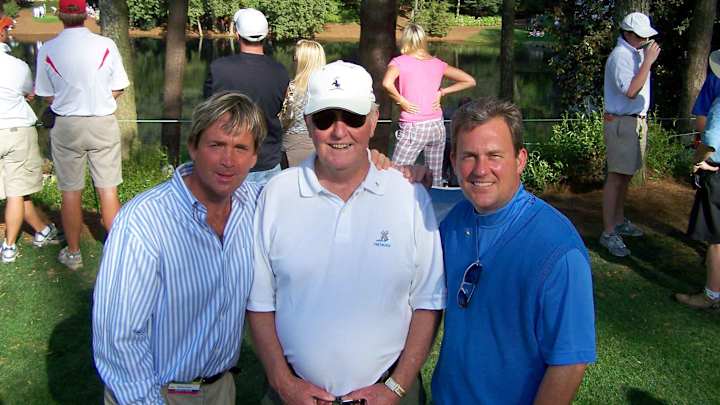

During the annual trek to Augusta, David Whitfield became a top-notch junior golfer and played at the University of North Carolina. The 1982-83 team, during Whitfield's senior year, was particularly notable for the names on the squad, including 1984 NCAA medalist and future PGA Tour winner John Inman, World Golf Hall of Famer Davis Love III and Jack Nicklaus II, the oldest child of Jack and his caddie in the 1986 Masters victory.

One team victory during the 1982 fall season further indicated the Whitfields’ love of the Masters. The Tar Heels won the Forest Hills Invitational that October at Forest Hills Golf Course in Augusta, a college event hosted by Augusta College (now University). The biggest perk, even though not highly publicized, came when the winning team’s entire roster, not just the five who played the tournament, were invited back to Augusta the following February to play Augusta National. It probably didn’t hurt, either, that Nicklaus was a sophomore on the team.

When David Whitfield alerted his father about the playing date, the Mercury Marquis departed Durham at 4 a.m., for Augusta. Buddy Whitfield met coach Devon Brouse and the Tar Heels at their hotel and rode down Magnolia Lane with the squad in their UNC travel van.

“Jackie gave us this great tour of the clubhouse – the Champions Locker Room, the Crow’s Nest, the Trophy Room, everything,” David Whitfield recalled. “It was awesome; our first time in the clubhouse. And then we went to the pro shop to get ready to play.

“I will never forget that scene. We’re standing in there and Dave Spencer, one of the pros, is asking who’s who, checking his list to give out tee times with three players paired with one member. He gets to Dad and asks, ‘And who is this gentleman?’ I told him it’s my dad who drove down from Durham to see us play here. Well, he said we don’t allow spectators on the course. And I’m sorry sir, but we’re going to have to ask you to leave the grounds. Dad smiled, they took him back to his car and he went on back home five hours to Durham. That’s quite a trip in one day, but he said the 45-minute tour was absolutely worth it.”

Whitfield's letter-writing campaign ended when he was informed in the summer of 1992 that his climb up the waiting listing was complete. At the same time, his mother-in-law, Eva, in Columbia received two. “Now, we gotta keep you alive for a few more years,” he would joke with her. Two tickets, at $200, were mailed to Whitfield in time for the 1993 Masters and have been bound for a Whitfield address every year through 2019.

The Routine

As time moved on, Buddy Whitfield would hold court with the same folks and always a different set of people would converge as he was encouraged to tell his Masters ticket story. J. Fleming Norvell, an Augusta National member and longtime starter on the first tee, stopped by to say hello, as did a few other members and leaders of various golf clubs and organizations. Whitfield was a familiar face. There’s no bragging, just sharing, with Whitfield sometimes propped on a spectator stick under the shade of the tree at the clubhouse and occasionally wearing a worn, white "CBS Golf" hat. Somebody new would come from Atlanta or Durham at the Whitfields’ invitation and gawk at the place that was so familiar on TV but so different in person.

You could explain what Cameron Indoor Stadium, Duke’s bandbox of a gym for its famous basketball program, looked like during numerous regionally and nationally televised ACC games of the week. But you couldn’t pass along the experience of the ancient building’s wave of heat on a cold winter’s night or the cramped positioning of the television and radio crews in the rafters and the “Cameron Crazies” overhanging press row at courtside. The same was true for Augusta National, walking in behind the veil of trees onto the garden-like grounds, having your feet touch the perfect turf, your hamstrings cry walking the unexpected steep hills or really thinking that a pimento cheese sandwich ain’t that bad.

The Whitfields’ longtime friend, Chapman, first visited the Masters in 1970 as a 9-year-old and was behind the first green with his father, Don, when Japan’s Takaaki Kono holed his second shot in the final round. Kono spotted the blond-headed Chapman and gave him his Dunlop golf ball, an offering that was recounted by Dick Schaap in his 1971 book, The Masters: Winning of a Golf Classic.

“Imagine your first visit to the Masters being written up in a book? It’s no wonder my first visit solidified my impression of the Masters,” Chapman said.

That keepsake was recently recovered, thanks to a find by David Whitfield, as Chapman has made many moves since growing up in Durham to become a national traveler as a golf course developer, including stints with Nicklaus and Palmer. He was particularly tight with Palmer, developing The Tradition Club and Arnold Palmer’s Restaurant in Palm Springs, California, and serving as Palmer’s caddie for the King’s 2007 Masters Honorary Starter debut. The former N.C. State golfer and board member with the Ben Hogan Foundation (his hero) has been a Masters attendee alongside the Whitfields for many years since 1975. He holds a reverence for Buddy Whitfield’s dedication to doing things the right way and for Doris, whom he called “Mom” since his mother died at a young age.

“Top was so engaging with people, such an amazing salesman, not just when working, but he sold himself,” Chapman said. “That’s something I learned to try to do myself – ask more questions of who you’re talking to instead of talking about yourself in a conversation. He always had a way with people where they truly felt like he was interested in them. He was a genuine guy, a man of his word. Trust was a big reason he was able to get tickets all that time.”

A dozen years ago, most of us didn’t know that Buddy Whitfield had been having difficulty with prostate cancer for a couple years. Palmer, a prostate cancer survivor, and CBS’s Jim Nantz were among those who sent notes of encouragement. Immediate family members passed along their pep talks to a man who didn’t ordinarily need or want one. He even called me weeks before he died in the summer of 2010 to commiserate about a recent job loss I had sustained, with nary a mention of his own predicament. That was Buddy.

When Buddy Whitfield passed on Aug. 10, 2010, he was buried in golf attire and an Arnold Palmer umbrella pin on one collar. All of us Masters veterans from Durham who had been with him at various tournaments — not just the Masters — discussed some type of celebration at the 2011 Masters. We knew that Doris, Whitfield's widow, would receive the two tickets, following the Masters policy of a pass-along to a spouse.

We finally agreed to take a green Masters folding chair, his extremely worn-in, brown-and-white saddle oxford golf shoes and ancient spectator seat stick and place them in a different place every round. Under the tree on Thursday. At No. 7 on Friday. Amen Corner on Saturday. Behind 18 green on Sunday. It was a low-key placement known to just a handful of folks.

It was the perfect understated testament for his enjoyment of the Masters and the similar passion he had instilled in all of us.

When Doris Whitfield passed at age 91 in September 2021, there was discussion their son's continuation of his father’s letter writing and hope that a sympathetic pass down to a child would come about, such as has been rumored occasionally among Augusta residents with long histories of Masters attendance and to retain the local presence. But that’s a story for another year, as friends and associates promise to rally around the streak’s continuation.

A Nicklaus celebration

There is still one more anecdote worth sharing. It was 1986, my second Masters of what will be 38 consecutive this spring. I usually hung with the Whitfields for a while during a round before returning to the Press Building adjacent to the first fairway. But that Sunday was shaping up to be quite memorable, so the stay was extended. The Whitfields were Nicklaus fans — just look at any 1970s-1980s weekend CBS broadcast and you’ll find the two Davids ensconced behind the 15th tee box to get some camera time, especially when Nicklaus was there. So even if Nicklaus wasn’t in the mix halfway through 1986’s final round, it was customary to support him for a while. When he made a birdie putt on No. 9, it seemed more pomp than circumstance. However, Whitfield had a challenge.

“I believe we all need to have a Budweiser on Jack for making that putt. And we’ll have another for each one on the back,” he said.

We had no choice. We all got Budweisers near the main scoreboard, and the Clydesdales emerged. Concession stands and restrooms were crowded on that back nine. Birdies on 10 and 11 – Buds at Amen Corner. “We’ve got to have another Weezer,” Buddy Whitfield would announce. Birdie at 13, eagle at 15, birdies at 16 and 17. It felt like a keg was consumed during that finish for Nicklaus' sixth victory, for which we claimed a liquid assist. Maybe that’s what helped or hindered my writing for the hometown dispatch that evening.

It was at that same Masters that Mac O’Grady, the talented but quirky veteran golfer, made his Masters debut. Known for his mystical swing thoughts and unique perspective, he was asked about the Masters experience.

“The Christians go to Jerusalem to find their spiritual tranquility or serenity, the Muslims go to Mecca, rock fans go to rock concerts, and golfers, like the birds of San Juan Capistrano, they migrate to Augusta,” O’Grady said.

Then he paused and smiled, “It’s like making love the first time. You never know what it’s like until you do it.”

I’m sure he was channeling Buddy Whitfield.