More People Should Know How the Greensboro Six Helped Change Golf Forever

I was back home in early October to watch 36-year-old JR Smith make his unique college golf debut when I learned that golf’s social battles have even deeper roots in the Old North State than I knew before I learned of the Greensboro Six.

It is surprising to me their story is not a widespread historical fact. That’s especially true for me, a native North Carolinian who grew up playing golf among folks from all walks of life at a municipal course in Durham with its own muddled history.

My discovery began during conversations with Richard Watkins — N.C. A&T State University’s friendly and groundbreaking men’s and women’s golf coach — to talk all things JR. It became apparent that the depth of Watkins’ story told of an impact golf had which is not shared as fervently as it should be.

Watkins grew up in Greensboro, a Black youngster introduced to the sport as a caddie who grew further involved as a player, golf shop worker, instructor and coach.

Watkins was the first Black golfer to play at High Point College from 1973-76 and spent roughly 20 years working at Gillespie Golf Course in inner-city Greensboro, a pinched-in course with few accolades.

He has coached the men’s and women’s squads at A&T since their inception five years ago and encouraged me to visit Gillespie Golf Course to learn more about the Greensboro Six.

“There are a lot of Gillespies across the country,” Watkins said. “City course. City owned. Everybody’s tax dollars maintained it. But everybody who was paying taxes on it then couldn’t play it.”

Gillespie, originally called Gillespie Park, is Greensboro’s oldest municipal course, cool because it has thrived despite years of under-appreciation and major blockades.

A 1941 Perry Maxwell design funded largely by the Federal Works Progress Administration, it’s located in the heart of North Carolina’s third-largest city on East Florida Street and bordering Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, approximately two miles from the A&T campus.

With land for housing scarce over the years, Gillespie eventually became a nine-hole course. But city recreation leaders brainstormed a system in 1991 where alternate tees on each hole created a 6,400-yard, par-72 course with different lengths or pars on each nine. For example, the fourth hole is a 176-yard par 3 and on the same land the 13th hole is a 338-yard par 4. Players making the turn alternate with those beginning their first nine. A First Tee facility, driving range and short course are located next door. A cafeteria-style restaurant, called the Gillespie Grill, takes up much of the small, one-story clubhouse, with reasonably priced “authentic, soulful and tasty” menu items. It costs $20 to play 18 holes.

“We’re not cheap, we’re inexpensive,” said Bob Brooks, the Gillespie Director of Golf.

The persistence, more importantly, points back to that historic moment which should be better known. The Greensboro Six, a group of six Black Greensboro golfers, integrated the course 66 years ago on Dec. 7, 1955 — just a week after Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of a Montgomery bus — and set off escalating legal battles all the way to the Supreme Court four years later.

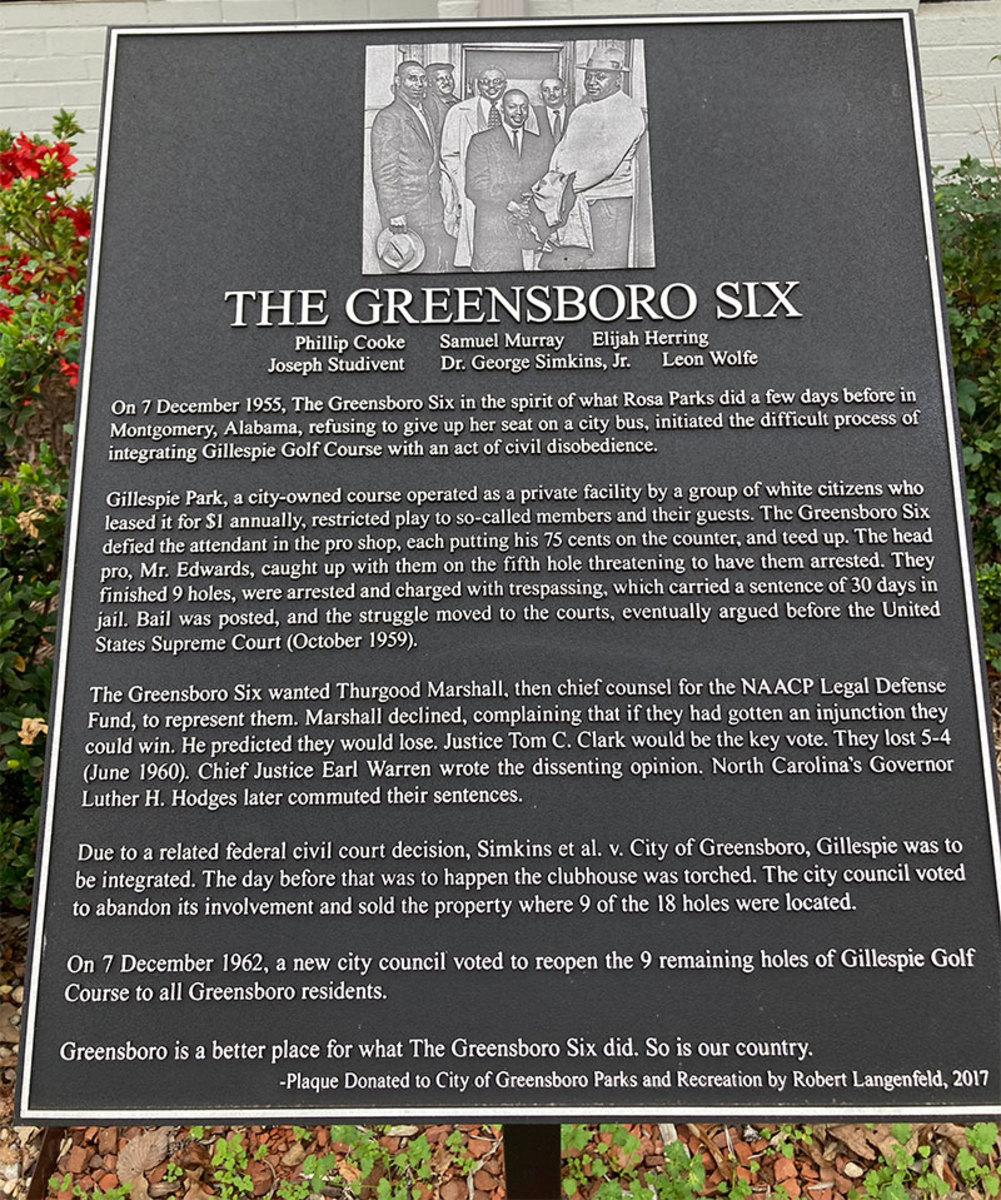

The gentlemen, remembered on a historic marker near the clubhouse (above), were tired of the shaggy conditioning and putrid smell from a nearby sewage plant Nocho Park. their nearby Blacks-only course. So, Dr. George Simkins Jr., a prominent second-generation dentist, champion tennis player and golfer, took his usual Wednesday afternoon off, departed his nearby Dudley Street home and led the charge to tee it up at Gillespie just two weeks before Christmas.

The course had been altered to a whites-only private facility on public land with a $1 lease agreement in 1949, an all-too-frequent move by cities to avoid civil rights requirements. Each player placed the 75 cents green fee on the clubhouse counter, wrangled with the club manager about signing in, started their round and were confronted by the angry club pro midway through the front nine. They were arrested later that evening for trespassing following their nine-hole christening.

“(The club pro) cursed us and threatened us and called us everything under the sun,” Simkins said in a 2000 interview with the Greensboro Public Library, indicating he held a golf club to play but also to defend himself if necessary. “So, I told him, ‘We’re out here for a cause.’

“He said, ‘What damn cause?’

“I said, ‘The cause of democracy.’ “

That move predated, and influenced in a large way, the more nationally celebrated Greensboro lunch counter sit-in by A&T students nicknamed the Greensboro Four, in February 1960 at the segregated F.W. Woolworth’s store.

Simkins was asked to participate in the Woolworth’s sit-in but opted out because his plate was already full of civil rights efforts, as he had become a 25-year leader of the Greensboro chapter of the NAACP, with trailblazing voter registration, recreation, education, health and political access movements.

One of the questions developed in the voting rights campaign in the late 1950s was aimed at potential politicians: “Do you intend to open up Gillespie Park so that everybody can play there? Otherwise, we’re not going to vote for you.” Doc, as he was called by friends, was eventually honored by Coretta Scott King in 1982, and a statue honoring his civil rights work was placed on the lawn of the Old Guilford County Courthouse in 2016, 15 years after his death at age 77.

It was further indication of Greensboro’s impact in golf. Gillespie was a regular stop on the all-Black United Golf Association for the Gate City Open from the early 1950s through the end of the century, with the Thorpe brothers, Lee Elder, Charlie Sifford and Jim Dent among the most notable participants and winners. Sifford, a Charlotte native, became the first Black man to play in a PGA Tour event in the South at the 1961 Greater Greensboro Open, with encouragement from Simkins. Sifford rotated his accommodations between dorms at A&T and friends in the community to stay out of sight of haters when not playing at Sedgefield Country Club. Tiger Woods’ son, Charlie, is named for Sifford.

The Greensboro Six case lost 5-4 in the U.S. Supreme Court in June 1960, mainly because of the failure by attorneys to present the declaratory judgment from a successful first federal hearing to the N.C. Supreme Court and beyond. But it drew considerable attention. Thurgood Marshall, chief counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and a Supreme Court Justice a decade later, was recruited to argue the case but declined, seeing the legal errors and presumptive defeat, but still assisted with extensive paperwork funding. It was just a few years after he successfully carried Brown vs. Board of Education in 1954 before the Supreme Court.

“Your lawyers ought to be the ones to go to jail for messing this case up like they have,” Simkins recalled of Marshall’s response. “I am not going to ruin my win-loss record by taking this case.”

Chief Justice Earl Warren’s dissenting opinion questioned the access to public facilities and N.C. Governor Luther Hodges commuted the sentences of the six men — Simkins, Phillip Cooke, Joseph Sturdivent, Samuel Murray, Elijah Herring and Leon Wolfe, all now dead for more than 20 years.

The clubhouse was burned down by arsonists before access was given in late 1957 after one court proceeding, and the city, for some reason, condemned the entire property.

The city left the recreation business for the next few years, finally opening again as the currently constructed nine holes on Dec. 7, 1962, with Simkins striking the first shot just as he did seven years prior to the day.

This revelation hit home even harder. Hillandale Golf Course is my home course in Durham and was in jeopardy of closing a decade ago in a tug of war between a tapped-out trust and a city trying to find a place for golf. There was a notable find in the course’s history.

In 1939, original owner John Sprunt Hill, a golf enthusiast and well-heeled and well-thought of philanthropist for the city of Durham and the nearby University of North Carolina, willed the course to the Durham Foundation to preserve it as a golf course or parkland. Copies of deeds contained this statement:

“... for general recreational purposes by the white citizens of Durham, City and County...”

That language continued beyond Hill’s 1961 death in documents for at least a decade, even adding “... as a Golf Course for the recreation of white citizens, and no other, of the City and County of Durham.”

Finally, by the early 1970s, the wording was changed to “the best interest of the community.”

Hillandale’s positioning within a non-profit trust led to the eventual dismissal of the racist practices, according to Zack Veasey, who grew up playing there in the 1970s and is the former President and Director of Golf at Hillandale.

Federal regulations prohibited exclusionary practices in tax-exempt status, which at first kept Hillandale from serving food and drink in the clubhouse for a time in the early 1970s. Golfers were served out of mobile food and drink trucks that were stationed around the course and dispersed from the nearby Coca-Cola plant.

There was no drama like Gillespie, but the courts ruled for desegregation by October 1970 and out of this discord came an opportunity for everyone to play golf.

That included the formation of the Bull City Golf Club, the largest minority-run golf club in the country during the 1970s and ’80s. The Thorpe brothers from nearby Roxboro, N.C., led by PGA Tour pros Jim and Chuck, played many rounds at Hillandale and frequented Gillespie, about an hour away.

Today, Hillandale experiences one of the most diverse and robust clienteles of any city municipal course, mixing college students and faculty from nearby Duke, UNC and N.C. Central with professionals and laborers from around the Triangle area in addition to vital community events supporting hospitals, veterans and children from all over the area. Rounds will total nearly 50,000 this year.

Hillandale was far from alone, sharing a similar sketchy past with dozens of courses around the country.

Lions Municipal in Austin, Texas, by most accounts was the first course to desegregate in the early 1950s. Today, Ben Crenshaw is leading a charge to protect the course as the University of Texas says it needs additional student housing and development.

Atlanta had a similar reckoning in the summer of 1955 when Blacks played golf, went through the court system all the way to the Supreme Court and opened public golf to everyone in the city just two weeks after the Greensboro Six played.

The Augusta (Ga.) Municipal Course, better known as “The Patch,” experienced a similar episode to Gillespie in 1964 when a group of Black men played the course, opening the door for many of the game’s greatest caddies to play the public course not far from where they carried bags at the Augusta National Golf Club and in the Masters Tournament.

The effort to further the Greensboro Six story is still in the works.

Dr. Robert Langenfeld, a retired English professor at UNC Greensboro, has been interested in Gillespie since joining the UNCG faculty in 1986. He has played Gillespie many times and wondered why the integrating group wasn’t celebrated more widely. He funded the current plaque on display outside the clubhouse entrance.

An effort to erect a N.C. Highway Historic Marker was voted down because “they lost the Supreme Court case,” Langenfeld said. An application to create recognition via the N.C. Civil Rights Trail with an accompanying plaque is pending.

The International Civil Rights Center & Museum, located two miles away from Gillespie at the old Woolworth’s location in downtown Greensboro, had a small mention of the golf effort upstairs in its museum for years. It's expanding the exhibit in 2022 to a more prominent, downstairs location to further recognize Simkins and the Greensboro Six, according to CEO John L. Swaine.

The museum also holds a charity golf tournament each summer in Simkins’ honor. Fayetteville dentist Dr. Ernest Goodson is leading a push to recognize Simkins and other dentists’ role in the civil rights movement at the museum.

“By and large, these are the stories of legend among the golf fraternity,” Watkins said.

Legendary, as in there is doubt because of the lack of detail.

Gillespie’s integration story and breakthroughs at numerous other golf courses need to be understood just as prominently as any course birthdate, architect’s work or notable tournaments. Because in golf, bogeys and birdies are always included.