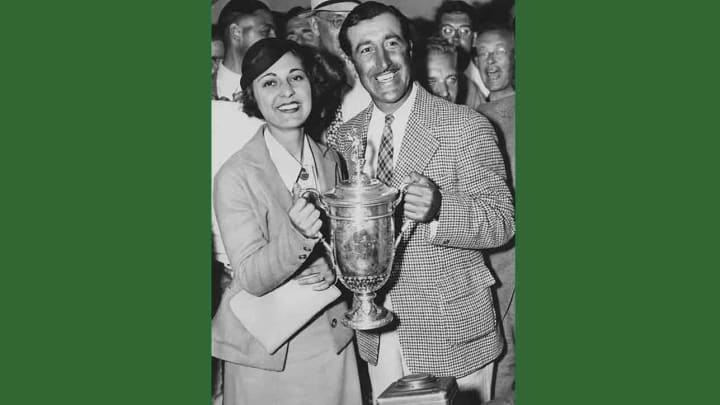

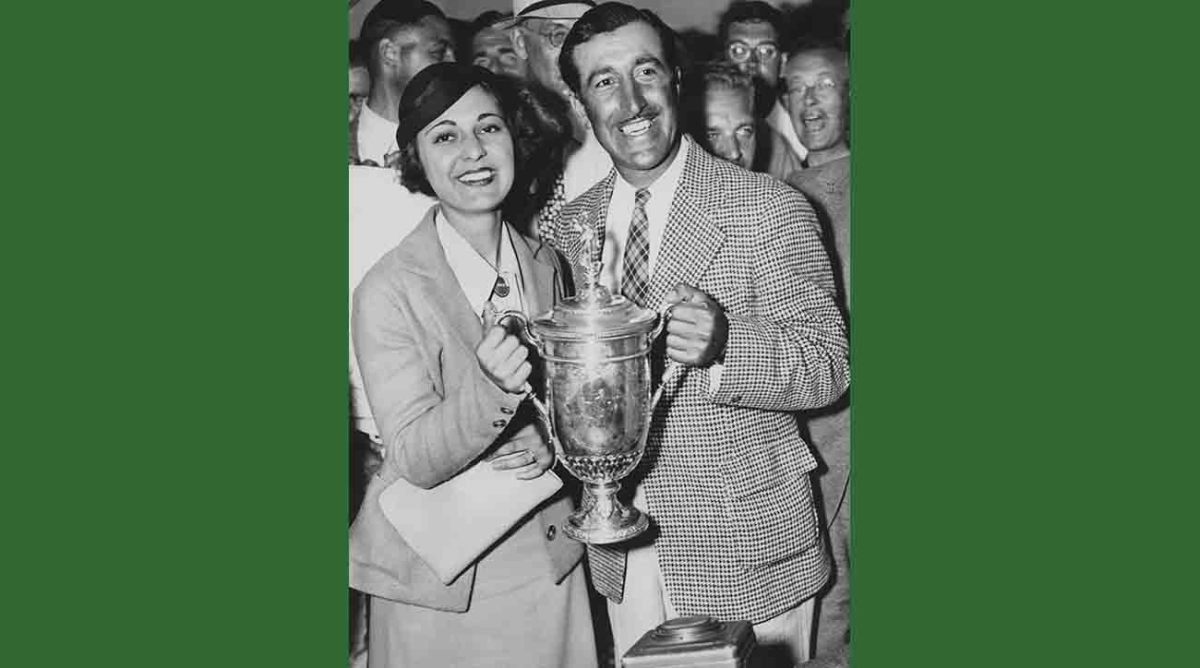

Remembering Tony Manero, the Surprise Winner of the 1936 U.S. Open

There are two little-known protagonists of this tale, and one very well-known key “character“ actor.

Our first protagonist is British-born Harry "Lighthorse" Cooper, who had a direct nexus to golfing royalty: his father had apprenticed with Old Tom Morris. His mother was also a golf professional, which was quite rare at that time. The family moved to Dallas when Harry was young, and he was a bit of a prodigy. His first tour win came when he was 19, and he eventually won 30 times. But nary a major championship (unless one believes the Western Open, which he won, used to be a major).

Ultimately snakebit at majors, Cooper lost a U.S. Open playoff, and had 10 top 5s in majors. Very impressive stuff. And, interestingly, he never played his birth country’s open. Cooper is on the very short list—and maybe at the top—of “best player to never win a major.” He won the first Vardon Trophy, in 1937, and until surpassed by Vijay Singh in 2008, his 30 tour wins were the most by a foreign-born player.

When he retired, he became a well-respected club pro; for the last 47 years of his life he was the head pro at Metropolis in White Plains (1953-78) and thereafter a teacher at Westchester Country Club (1978-2000), a truly remarkable career of longevity. He is a member of the World Golf Hall of Fame.

Retired Westchester Country Club head pro John Kennedy remembers Cooper well as a classy gentleman and first-class ambassador of the game and of the club. “He took young teaching pros under his wing, and to my knowledge never complained publicly about his majors disappointments,” Kennedy says. “Harry was no one-hit wonder. For years his fellow pros regarded him as the finest striker of the ball on tour, so much so that his nickname was ‘Pipeline’”.

Our second protagonist is Tony Manero, born in Elmsford, N.Y., and certainly not into a golf family. He came up through the caddie ranks, and became lifelong friends with one Eugenio Saraceni, a fellow Westchester County caddie better known as Gene Sarazen. More later on the Sarazen relationship in a bit.

Manero is also on an-all time golf list—that of “unlikeliest players to win a U.S. Open." His victory is still regarded as one of the greatest upsets in U.S. Open history.

Manero died in 1989 at age 84 and did not have nearly as distinguished a career as Cooper: “only” eight tour wins, but one was the 1936 U.S. Open—striking a blow for former caddies and longshots everywhere. He did play on a Ryder Cup team and was well-respected on tour, but he had only one real shining moment and it was a beaut.

Manero also married into a popular restaurant family, the same-named Maneros, whose family-oriented steakhouses were incredibly popular from the 1950s through the early 2000s in Connecticut and Florida. On any given Saturday night in Greenwich, Conn., many CEOs and Wall Street titans (and youngsters aspiring to be the same) could be found with their families waiting in line to get into Manero’s (no reservations allowed).

The walls were covered in photos, mostly relating to golf and the Manero family. But one non-golfer photo, from the 1970s, was perhaps Nick Manero Jr.’s favorite as he once relayed to me—the one with three young men just out of school visiting at the Great Wall of China, proudly holding up the famed Manero’s paper menus (all three went on to have fabulous Wall Street careers—Johnny and Peter Weinberg, and Jamie Kempner).

Manero Jr. remembers “Uncle Tony” well; Nick’s father, Nick Sr., founder of the chain, had a sister who was married to Tony. Nick Sr. and Tony were thus brothers in law, and hence Tony’s bride was officially Mrs. Manero Manero. The Manero men were all avid golfers and belonged to Westchester Country Club, where Harry Cooper was ensconced as of 1978.

It was a different world back then, says Nick, and Tony worked at the family restaurants in his retirement, as a family host of sorts, affable, well-dressed and loving life and his status as a major winner, in spite of—or perhaps because of—how much of a long-shot he had been. I remember him well there, and he was a real value-add to visiting the restaurant.

People loved him. According to Nick, “Tony was a delightful, charming, witty gentleman who was not a real drinker, but he did drink with Bobby Jones.” Family lore has it that Jones shared some moonshine at a cabin on premises during a Masters, and Tony quite enjoyed himself.

Tony had two sons, one of whom, Dick, went to Dartmouth and Yale Law, pleasing Tony, the ex-caddie, no end. One of Dick’s law partners was the son of a Manero’s restaurant cook, as the circle goes round and round.

Tony would not practice that much but had a gift, and was a tremendous player well into his 70s. For many years he was the head pro at Sedgefield Country Club in North Carolina in winter, and took folks to the Caribbean often to play golf. He did a stint as an assistant at Pinehurst as well when he was young.

But he is the forgotten man. He lived in Greenwich until he died and years ago, when Lee Janzen won the U.S. Open at Baltusrol, the local papers failed to note that one of its distinguished residents had done the same many years before. The family was hurt.

The 1936 U.S. Open

Manero needed to qualify to play in the tournament, and at that rather lucky to make it in at all. During one of his qualifying rounds, he had to hole a chip at the last in order to slide into the tournament. Very few qualifiers have won the US Open.

It was a wild and unforgettable finish.

Entering the final round, Cooper led Manero by four strokes. Cooper was several holes ahead of Manero, whose final round 5-unde- par 67 was a then-course record and gave him a 72-hole total of 282, which was the new U.S. Open four-round record. Cooper could only muster a 1-over final round 73. The previous U.S. Open record of 286 was set in 1916. Cooper’s 284 at Baltusrol thus stood as the US Open record—for all of 30 minutes.

His victory was not without controversy. Part of that is because he was paired in the final round with his dear friend Gene Sarazen, whose tournament record he would break in 1936. The Squire apparently requested the pairing, believing his presence would help the emotional Manero keep an even keel. It was a different era.

Cooper would claim that the combination of Sarazen coaching up Manero, an unruly gallery and a pickpocket cost him his major, and the final holes provided all the drama.

“The 16th hole was a par-3 and there was a big crowd following me," Cooper said in 1991 Los Angeles Times story. "They were standing in between the traps and around the green. I kept waiting for them to move, but there were no gallery marshals then, no ropes. So I said, ‘To heck with it,’ and hit the ball. It hit someone up at the green and bounced into a trap. I would have been on the green.”

He did not get up and down.

“So I took a bogey there, then got my par at 17 and then hit two fine shots at 18. I was 40 feet from the hole in two," he continued. “I waited for eight minutes for my playing partner to get to the green. Someone had picked his pocket. I probably got a little nervous and three-putted the damn thing. Manero got a 3 on the hole and beat me by two strokes.

Afterwards, a complaint was filed with the alleging that Sarazen was actually giving on-course advice to Manero, a violation of the rules. After a meeting, the USGA ruled that there was no evidence of any wrongdoing, and Manero was allowed to keep the championship. But a whiff of taint has lingered over the outcome ever since, fairly or not.

Rather understandably, Lighthorse Harry, despite some ensuing fine play in majors and more close calls, could not forget this particular one that got away.

“Privately, Harry firmly believed he had 'won' three majors but that some combination of bad luck and exogenous forces took them away," Kennedy said.

Cooper lost an 18-hole playoff to Tommy Armour at the 1927 U.S. Open and was second at the 1936 Masters, one behind Horton Smith. He was also T2 at the 1938 Masters, two shots behind Henry Picard

The last word on Cooper and Manero belongs Nick Manero Jr: “Many years later—had to be in the 1980s or so—Lighthorse Harry came into the restaurant. My uncle was there greeting and chatting. I heard Harry tell him ‘you old so-and-so, Baltusrol was the last best chance I had to win a major and you took it from me,’ and not exactly said with a smile ... a lot more surly than wistful or funny."

And Tony Manero? Smiling, content and classy to the end, very secure that he was a surprise, and very proud, winner of the 1936 U.S. Open.