Ted Ray Was Golf's Original Long Driver and a True Original

Golf appears to be in the age of the long hitter with the advent of Bryson DeChambeau who, after a new diet and lots of hard work in the gym, routinely belts out drives of 350 yards or so, and with his strength can play from heavy rough when his drives go astray. Others have preceded DeChambeau as big hitters in recent years — Palmer, Nicklaus, Daly, Tiger and Dustin Johnson readily come to mind.

None of this is new. The advent of the wound Haskell golf ball in 1899, which replaced the old gutta percha ball, began the age of the modern long drive. The Haskell flew farther, so much so that courses had to be lengthened.

And the first long driver was a stout Englishman, Edward Rivers John Ray, known to all as “Ted.” He was born in 1877 on the Isle of Jersey, one of the Channel Islands, 12 miles off the coast of Normandy. Jersey is a small island, not one you’d expect to produce top professional golfers, but not only did Ray hail from Jersey, so did Harry Vardon who would win six British Opens.

Ray was a big man, over 6 feet tall and weighing in at 16 stone (225 pounds). His theory for distance was simple — hit the ball as hard as he could, with maximum speed at impact. No training in the gym, no special studying of the golf swing, no Trackman. More like John Daly’s “grip it and rip it.” A typical Ray lesson went like this: “‘it ‘em ‘ard, mate, like I do.” Students complaining that they still had trouble were told, ‘Well, then, ‘it ‘em a bloody sight ‘arder.”

Ray was self taught and learned golf with borrowed clubs, sometimes playing a round with a single club which allowed him to experiment and learn a variety of shots. Ray became a proficient golfer and moved to England to become a golf professional.

Like all professionals of the time, Ray was a club pro. After some minor positions, he took the professional position at Ganton Golf Club in 1903 and left there in 1912 to take the position at Oxhey Golf Club where Ray remained for the rest of his golfing years.

But Ray was more than just a long driver, he was a winner with a total of 46 professional victories. Many professional competitions at the time in Great Britain were played over 36 holes on one day so as not to interfere with the club job. However, Ray won the British Open in 1912 at Muirfield, 72 holes over two days, leading wire to wire. Ray qualified for every British Open from 1899 to 1932, and had 12 top 10 finishes. He also won the U.S. Open in 1920 and was the playing captain of the British team in the inaugural Ryder Cup in 1927 at age 50. He won his last tournament, the Herts Open, at age 57.

Ray had an unusual swing, but it worked for him. One journalist described it as looking like the “lurching charge of a Cape buffalo.”

Harry Vardon was a bit more sanguine in describing Ray’s swing, “He defies so many accepted principles of the game; he’s so very nearly a complete set of laws to himself. He sways appreciably and heaves at the ball. He is a master at recovering the right position at the moment of impact after having moved his head and body during the backward swing in a degree that would spell disaster to almost anyone else. He is the brilliant exception to the safe rule. As he brings his club down…his tremendous lunge brings your heart into your mouth lest he should miss the ball. You wonder where the ball will go in the event of such a catastrophe…[however]…at the psychological moment he has done everything correctly….”

In defense of his odd swing, Ray met his critics stating, “I have been asked how I accounted for a player of my style — a style in many ways breaking the canons of golf — achieving success now and then, and I have invariably indulged in the Caledonian characteristic of answering one question by asking another: ‘How do you think I would fare were I to drop my present style?’”

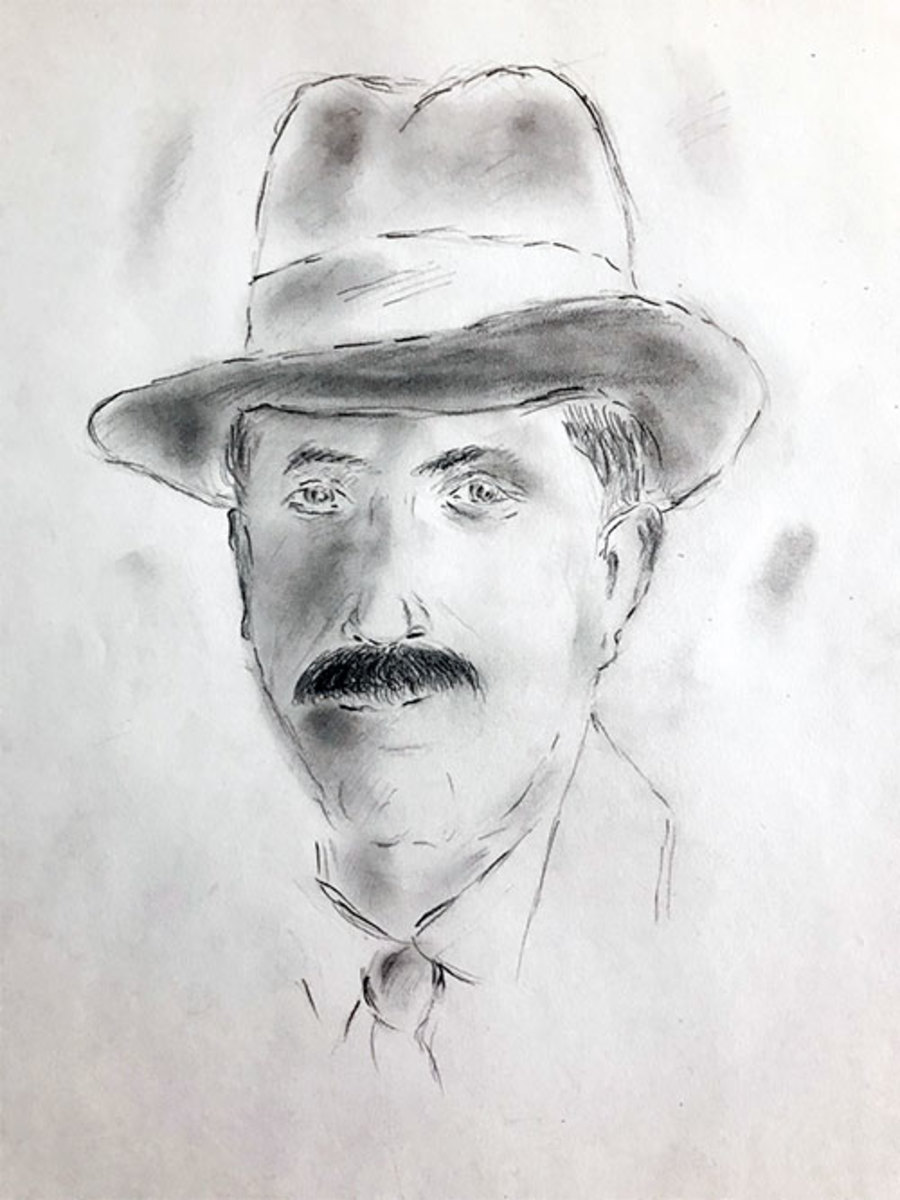

One can see why Ray was popular with galleries, an odd swing and off the tee his drive was almost always the longest in his pairing. In addition to his unorthodox swing, Ray wore long baggy trousers, and a shirt and tie under a baggy coat with large pockets stuffed with necessities, including pipe tobacco. Perched on his head was a felt trilby hat normally associated with street wear, not golf.

Glenna Collett Vare, the great American star of ladies golf commented that Ray “prefers to play in long trousers, and he prefers them somewhat worn and baggy. He was never a contender for the best-dressed golfer’s prize, but he has many cups. Clothes do not make the golfer….”

Ray smoked his pipe on the course and didn’t remove it from his mouth when playing a golf shot. Ray thought smoking calmed his nerves on the golf course.

At the 72nd hole of the 1920 U.S. Open at Inverness, Ray needed two putts to win. But as he got ready to putt, Ray realized his pipe had gone out; he stopped, pulled his tobacco bag from his coat pocket, refilled the pipe and calmly lit it. Only then did Ray resume his stance, two-putt for a par and a one stroke victory over Harry Vardon, Jack Burke, Sr., Leo Diegel and Jock Hutchison.

In Ray’s day, there were no yardage markers on the course, no rangefinders, and no television renditions showing exact yardages of any shots, so the distance of any shot was an estimate by players or golf writers, except when the shot was in a special driving contest with length measured. There were a few instances, however, when drives during play were fairly measured — when Ray drove the green from the tee or carried a hazard.

In 1913, prior to the U.S. Open, Ray and Vardon played a 36-hole exhibition match at Baltusrol Golf Club. Ray put on a long driving show by driving the 285-yard 12th hole twice, each time for a birdie; he reached a 550-yard hole twice in two strokes; and on the 10th hole, Ray drove his ball 320 yards, only to land in the moat surrounding the green. Unperturbed, Ray took out his niblick and struck his ball, which was sitting under two inches of water, landing it on the green and making his putt for a birdie.

During Vardon and Ray’s 1920 tour of the United States, it was reported at Brookhaven in Atlanta, “Ted thrilled the crowd again by hitting his drive on the 9th across a swamp, a forced carry of over 280 yards.” Also in 1920, Ray won the driving contest held at the Bramshot Cup in England with a measured drive of 273 yards.

In winning the 1920 U.S. Open, Ray drove the green at Inverness’s par-4 7th hole, a 334-yard dogleg left, by driving over a deep swale which formed the dogleg, a carry of 275 yards. He birdied the hole in each of the four tournament rounds. Many felt Ray’s daring play at the 7th gave him his one stroke victory.

While none of these distances seem extraordinary today, a very good drive in Ray’s day was 220 yards or so. He was way ahead of the pack. Sometimes his drives were off line, but Ray was a master of the niblick and had commented once that he’d rather play from the rough with his niblick than from the fairway with his mashie (roughly a 5-iron).

At the time, the niblick was akin to today’s 8- or 9-iron. Ray described his niblick as having slightly less loft than most, more like a mashie-niblick, so it was most likely what we would consider an 8-iron. He was very talented with his niblick and preferred to pitch his ball to the green rather than to play a low running shot which was the style of the time.

In his book, Down the Fairway, Bob Jones described watching Ray play an impossible approach after an errant drive on the 12th hole at East Lake Golf Club in Atlanta during an exhibition match. “[Rays’s] drive was the longest of the four, as usual, but right behind a tree. The tree was about forty feet in height, with thick foliage, and the ball was no more than the tree’s altitude back of it, the tree exactly in line with the green. As Ray walked up to his ball, the more sophisticated members of the gallery were speculating as to whether he would essay to slice his shot around the obstacle, 170 yards away, or “pull” around on the other side. As for me, I didn’t see anything he could do, possibly; but accept the penalty of a stroke into the fairway. He was out of luck I was sure.

“Big Ted took one look at the ball and another at the green, a fair iron-shot away, with the tree between. Then without hesitation he drew a mashie-niblick, and he hit the ball harder, I believe, that I have seen a ball hit since, knocking it down as if he would drive it through China. Up flew a divot the size of Ted’s ample foot. Up also came the ball, buzzing like a partridge from the prodigious spin imparted by that tremendous wallop — almost straight up it got, cleared that tree by several yards, and sailed on at the height of an office building, to drop on the green not far from the hole…The gallery was in paroxysms. I remember how men pounded each other on the back, and crowed and cackled and clapped their hands. As for me, I didn’t really believe it. A sort of wonder persists in my memory to this day. It was the greatest shot I ever saw.”

Ray was philosophical on his occasional visits to odd places with a wild tee shot saying, “Many roads lead to Rome, but some take us there quicker than others. I often complete the journey to that fair city in solitary company, my route untrodden by previous travelers.”

Ray was also an excellent with his putter. Three time British Open champion Henry Cotton thought highly of Ray’s putting skills, stating, “Ted was always a fine putter; often big men are. He had a lovely touch, a sort of combing action where the club face crept up the back of the ball and rolled over and over with the maximum top-spin. He was great at approach putts, and his aluminum putter, the Ray-Mills, had great success.”

The Ray-Mills putter Cotton referenced was designed by Ted Ray, an aluminum terraced top mallet which became a top-selling putter.

Golf journalist Louis Stanley said of Ray’s putting that he had a “feather-like touch with an aluminum putter which he wielded at times like an enchanted wand.”

As for Ray himself, he espoused no special style in putting and advised against suggestions from others, no matter how well-meaning they might be. Ray’s advice was straightforward: “Master your putter or it will master you, but as to how you may do this — I wish I knew. Just get out on to the green and practice; and let the inspiration come to you as and when it may.”

Willie Park, Jr., twice winner of the British Open, said, “A man who can putt is a match for anyone.” Ray’s rejoinder was simple: “I would analyze it this way. You cannot putt well unless you have approached well, and you cannot approach well if your drive has not been a good one.” And Ray could do all three.

Ray is little remembered today, but Ray, Harry Vardon and Tony Jacklin are the only golfers from Great Britain to have won both the British Open and the U.S. Open. If you want to add Northern Ireland to the mix, Rory McIlroy has also won both.

Ray was a popular superstar of his era, but found the game humbling, commenting, “Golf is a fascinating game. It has taken me nearly 40 years to discover that I can’t play it.”