Book Excerpt: The 1997 Masters was the True Beginning of the Tiger Woods Legend

From Tiger & Phil by Bob Harig. Copyright © 2022 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

We should have known. A few days prior to the start of Masters week, Woods was playing at his home course, Isleworth, in Orlando. It is where he befriended veteran PGA Tour player Mark O’Meara, who was nearly 20 years Woods’ senior.

The two became frequent practice round partners. O’Meara and his then-wife, Alicia, showed Woods the ropes around the neighborhood. They helped him get settled into his new home and recognized that he was still just a kid at heart, with no domestic skills, no decorating chops, no direction other than on the golf course. They looked after him.

And O’Meara was more than happy to play and practice with Woods. Not only did he enjoy the company but Tiger also inspired him to be better (O’Meara would, at age 42, win two major championships, including the Masters, in 1998). It helped him up his game as he already seemingly saw his best days on Tour.

But as if to forecast what was about to occur, on the Friday prior to heading to Augusta, Woods shot 59, an Isleworth course record. He shot 32-27 from the back tees, which then played to 7,179 yards and a USGA slope rating of 74.4. Basically, that means the course ranked among the toughest in Florida.

The next day, the duo decided to play again, and there was some money on the line: $10 automatic one-downs, meaning any time a player fell behind by a hole, a new $10 bet started from that point until the end of the nine holes.

Starting on the 10th hole, Woods birdied to immediately go 1-up, meaning a new $10 bet was triggered. At the 11th hole, a par-3, Woods had the honors and hit first.

“I haven’t even gotten out of my cart, but he hits it and it’s going right at [the flag],” O’Meara recalled. “It one-hops and goes into the hole for a hole-in-one.”

Before even attempting his own tee shot, O’Meara quit. “I put $100 on his cart and said, ‘I’ll see you on the range.’ ” O’Meara chuckled. “You’re 16-under par for 20 holes. I quit. I’m outta here.”

We did not quite know it at the time, but Thursday, April 10, 1997, was the true beginning of what would become the legend known as Tiger Woods. Yes, he’d produced all those amateur exploits. He’d already won three times as a pro. He’d just turned 21 a few months prior. But the opening round of the Masters was also the start of something special.

Per tradition, the defending champion Nick Faldo was paired with Woods, the reigning U.S. Amateur champion. The six-time major winner was coming off a victory (which would turn out to be his last PGA Tour win) at Riviera in Los Angeles. Despite having never played in a major championship as a pro, Woods was installed as an 8-1 co-favorite with Faldo and Greg Norman — the tough-luck loser to Faldo a year prior when he squandered a six-shot final-round lead.

It was not a smooth start, however, for Tiger. He appeared nervous on the first tee and hit an opening drive to prove it, launching it well wide of the fairway. He putted his ball off the green at the first hole and made bogey. He added three more on the front side, including the par-5 eighth and again at the ninth to take 40 strokes and stand at 4-over through nine holes.

But Woods gathered himself — he said he tried to return to the feelings of a week earlier when shooting 59 at his home course in Florida — and blistered the back with four birdies and an eagle. His 6-under-par 30 gave him a round of 70, just three strokes back of first-round leader John Huston (who holed a fairway shot for an eagle at the 18th, eliciting the Augusta Chronicle headline: “Huston, The Eagle Has Landed”). Faldo shot 75.

Woods got under par for the first time at the 15th hole, where he hit a pitching wedge to six feet on the par-5 and made the eagle putt to stand at 1-under.

“Going in it was, ‘What do you think of Tiger?’ Didn’t ask you anything [about yourself]. It was so total Tiger,” Faldo recalled. “It was unbelievable. It was so total Tiger it was annoying. He came in with such major attention. And he used it in his favor. No player before walked to the first tee with eight policemen around him. Suddenly Tiger decided he needed security. He had a whole different aura. An aura around him where everybody watched him and listened. And everybody wanted a piece of it. Yes, it was amazing.

“He went out in 40 and back in 30, and then we didn’t see him for the next 14 years. He left us in the dust. It was a special day. It was the way he went out in 40 and then to win by 12. That’s something pretty unique. [It’s like] you miss the first corner and then don’t see him for dust. That’s really what that week was.”

Woods was the center of attention. Instead of what appeared to be the calamitous beginning to his Masters, he turned it around stunningly and was in contention. He was in the second-to-last Friday pairing with Paul Azinger, who in 1993 won his lone major at the PGA Championship before a cancer diagnosis knocked him out for a year.

Woods was far more in control to begin this day, parring the first hole and then birdieing the second. His only bogey of the round came at the par-4 third, and from there he cruised to a 6-under-par 66 that included an eagle-birdie-birdie run at the 13th through 15th holes. He surged into the lead by three strokes over Colin Montgomerie at 136, 8-under par. Azinger shot 73 and dropped back into a tie for seventh, trailing by six.

When Woods made eagle at the 13th, hitting an 8-iron to 20 feet and rolling in the putt, he led the tournament for the first time.

“To me, I figured he’d be nervous playing with me,” Azinger recalled. “Why should I be nervous playing with him? He was 21. I didn’t even think about it. I doubled the first hole from the middle of the fairway, then played 1-under the rest of the day. I’m hitting 3-wood, 8-iron into No. 13. I’m hitting driver, 8-iron to 15. Those were big holes that changed the way it went. He hit 3-wood, pitching wedge to 13; I hit 3-wood, 8-iron. The first tee shot I’m thinking, ‘Holy crap.’ On No. 2, right down the middle, he’s got 6-iron, 7-iron into the green. And he didn’t miss a putt inside 10 feet. If you’re going to drive it great and not miss a putt inside 10 feet, who is going to beat you?

“To succeed [on Tour], you have to drive the ball well. You have to make putts, and you have to be the best wedge player. That week, he was all three. If you’re two out of the three, you can make cuts and make a living. If you have one of the three, you’re going to starve. But he had all three. Even if he missed a fairway, he hit it a mile.

“He was unaffected by the magnitude of what he was trying to accomplish. That’s what struck me. He wants to play well way more than he is afraid of failing. There were little things in my head that I envied in him because he wasn’t afraid of screwing up. Not everybody thinks that way. That’s an asset. You have to want it way more than you are afraid of failing. That was something that was very obvious to me. When people asked me about Tiger later in his career, I always said he wants it more than everybody else. That doesn’t mean we don’t want it. Best way to say it is the guy isn’t afraid. He’s less afraid of failure than anybody I’ve ever seen. As a result, he failed less often.”

The azaleas and the dogwoods had no chance against the onslaught. Augusta National was on fire.

Not only was Tiger leading but Montgomerie also shot a second-round 67 to get into the last group on Saturday. He was three strokes back, but Monty was an accomplished veteran in the midst of winning the European Tour’s Order of Merit (money title) seven straight years (through 1999). To that point, he posted five top 10s in majors, including playoff losses at the 1994 U.S. Open (to Ernie Els) and the 1995 PGA Championship (to Steve Elkington).

And he provided a bit of fuel for Tiger when he said following the second round, “There’s more to it than hitting the ball a long way, and the pressure’s mounting more and more. I’ve got more experience, a lot more experience, in major championships than he has. And hopefully I can prove that.”

All Woods did was prove Montgomerie’s experience didn’t matter. He played a near-flawless third round with seven birdies and no bogeys for a 7-under-par 65 while Montgomerie made three front-nine bogeys on his way to a 74. He dropped 12 shots back into a tie for sixth while Woods led the tournament by nine.

It was a remarkable display from Woods, especially for a 21-year-old playing in his first major championship as a pro. Woods missed a single fairway and just one green — at the par-4 third, where he saved par with a 10-footer.

“I’m probably the reason he did what he did,” Montgomerie said years later. “I played with Tiger on that famous day on the Saturday. I witnessed something very special that day. I thought I would beat him. I was wrong. And everyone else was wrong as well. But I admitted it. I’d just witnessed something very special. I thought I shot a very solid 74 until I lost to him by nine shots. I witnessed something that nobody else had seen. I was asked, ‘Will he win?’ He’ll win by more than nine. Of course he did. He won by 12.

“I’ll never forget it. I outdrove him on the first. I hit the back of the bunker, and it shot forward and I got him by a yard. I could have walked in. I don’t think I saw him again all day. I think he was 60, 70 yards ahead of me all day. It was phenomenal to watch him. He knew it was going in, and his caddie knew it was going in, and I knew it was going in, and everyone knew it was going in. The belief that he had that a ball was going to go in. Now Augusta is the most difficult to commit to and believe that the ball is going to go in the hole. Tiger had that belief at 21 years old. Incredible.

“I’ll never forget what I saw close at hand. I was the closest to it all day. That was very special playing with someone we’d never seen at the level. He shot 65, and it was the easiest 65 I ever saw. Just something different about it. Never witnessed anything like that. I didn’t really know what he was capable of. I felt I had experience over him. We could do something. I sorely misjudged him. And we all were. Nobody could have said what was going to happen, and that was the writing on the wall over the next 20 years. Very lucky to have lived in the era of Tiger Woods.”

Montgomerie spoke beautifully and admiringly of Woods and what he meant to golf. But there were numerous occasions during his playing career that he could be less than accommodating. His moods shifted with his scores, and among those who often covered his European Tour career, there was always a level of skepticism that his charm could be maintained. Monty waxed poetic on the Wednesday before a tournament; not so much when he missed a cut on Friday.

And so it was that the Scotsman surprised the assembled masses in Augusta National’s media center early Saturday evening by showing up to talk. Nobody requested him; nobody in their right minds ever thought he would want to talk after the beatdown that just occurred.

But not only did Monty take a seat in front of the scribblers, he also wowed them with his praise of Woods.

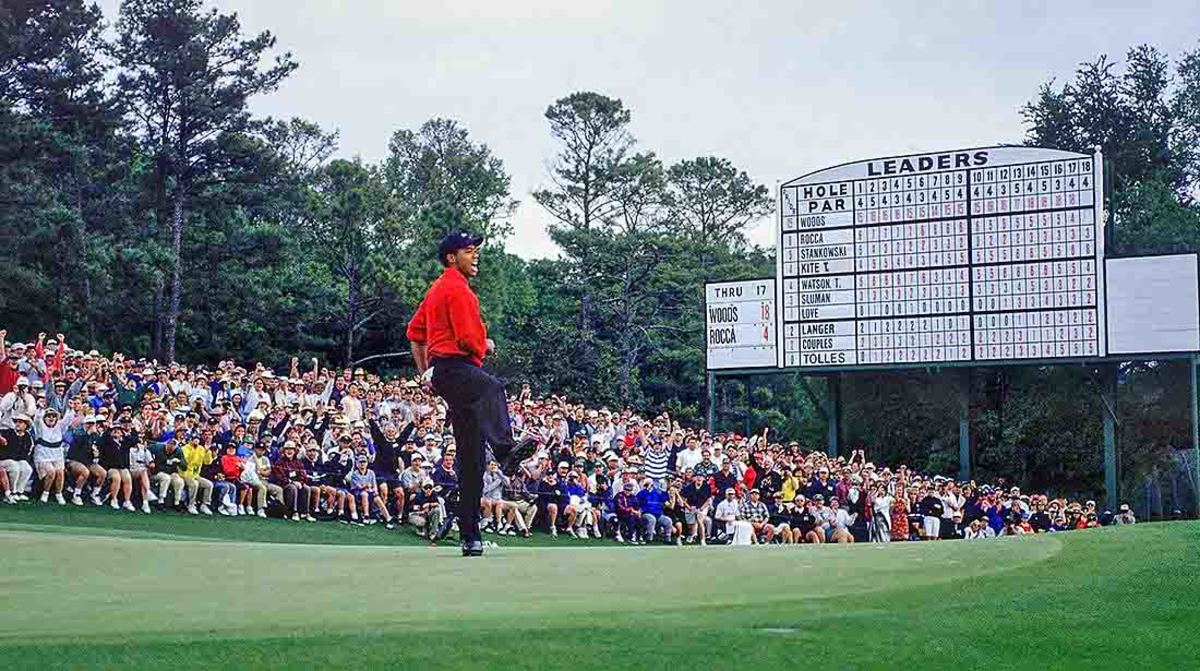

If there was any doubt about the outcome heading into the final round of the Masters with Woods leading Costantino Rocca by nine strokes, Montgomerie did his best to dispel it the night prior. “We’re all human beings here,” he said. “But there is no chance humanly possible that Tiger Woods is going to lose this tournament.”

Reminded that Norman let slip a six-shot advantage a year earlier, Montgomerie said, “This is different; this is very different. Faldo’s not lying second, for starts. And Greg Norman’s not Tiger Woods.”

Woods put to rest any doubts about squandering the lead by the turn after he made two birdies and two bogeys over the front nine. Rocca never got closer than eight strokes. At that point, all that was left was the 72-hole scoring record, which Woods set by shooting 3-under on the back — and converting a tricky par putt at the 18th — to finish 12 strokes ahead of Tom Kite.

It was a daylong coronation, a stroll amid the towering pines toward history. Woods, a man of color, took his place among the game’s greats at an event that did not invite its first Black player until the year he was born.

That man, Lee Elder, was in attendance at Augusta National when Woods made the world pay attention to golf. In fact, Elder wouldn’t miss it. He flew to Atlanta from his Florida home that morning and was driving — too fast — to Augusta when he saw the red flashing lights in his rearview mirror.

As the officer, who Elder noted was also Black, began writing out a ticket, Elder made his case to the Georgia patrolman. “I gave him the whole story,” Elder said. “I was telling him, ‘There’s history about to be made in your state. Tiger Woods is about to win the Masters. I’m just trying to get there before he tees off.’ He just kept writing and writing. When he got through, he gave me the ticket and said I either had to sign it or follow him to the precinct.”

And then there was the final kicker.

“He told me, ‘I don’t know who Tiger Woods is, and I don’t like golf,’” Elder said.

Few would not know the name Tiger Woods again after this day. Black workers at the club snuck a peek at him on the first tee and stood on the balcony of the old manor clubhouse, cheering him as he putted out on the 18th while his record-setting performance was witnessed, in part, by some 44 million television viewers during the final round.

Those who played with him could only wonder. At the time, they weren’t contemplating the social ramifications of his play; they were simply marveling at what was on display before them.

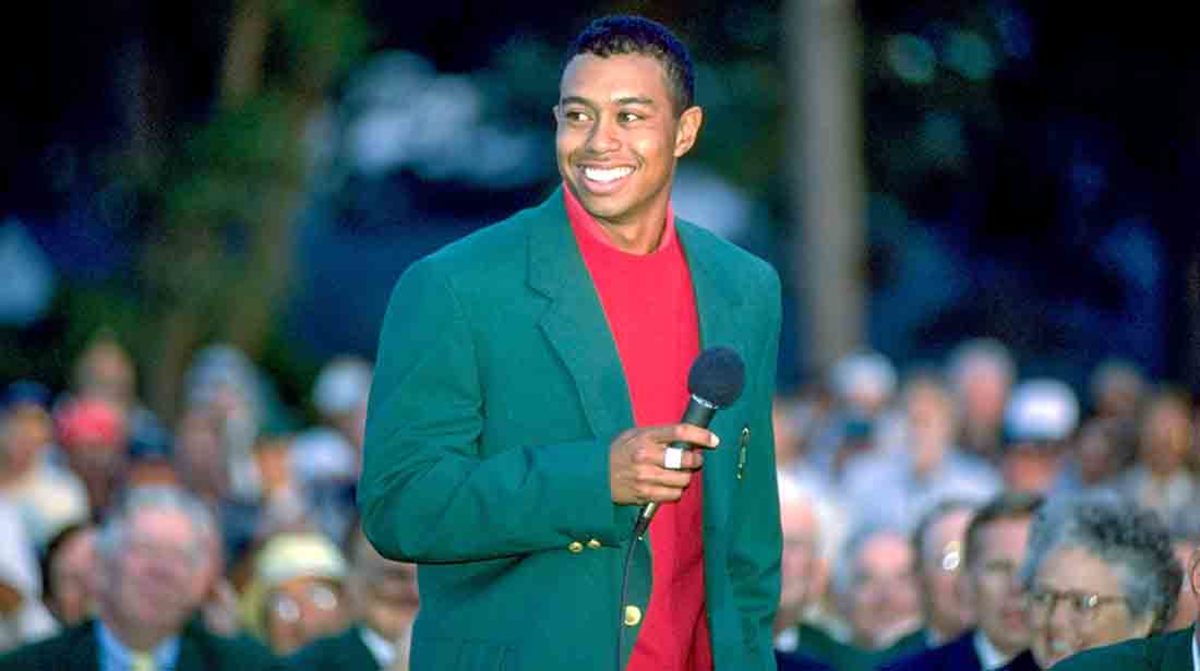

Woods set the tournament scoring mark of 270, 18-under par, and became the youngest player to win the title. His 12-shot victory was the largest in any major championship going back to the 1862 Open at Prestwick. There Tom Morris Sr. won by 13 shots — in a field that saw just eight players and on a 12-hole layout that was played three times — at a time when Abraham Lincoln was the U.S. president and golf had yet to be established in the United States. Woods later set the standard when he won the 2000 U.S. Open at Pebble Beach by 15 strokes.

In the immediate aftermath of his victory, Earl and Tida greeted Woods behind the 18th green.

The hug with his dad aired a million or more times over the years and played repeatedly for comparison when Woods won the Masters for the fifth time in 2019 and hugged his son, Charlie, behind the same 18th green. It was but one part of the dream realized for Earl, who boldly predicted such days would be common.

And yet it was difficult for anyone to envision such dominance. A victory in any major is a life-altering occurrence, but to do so by 12 shots? At Augusta National, where for so long Black players were denied their opportunity to play?

Before he could even get comfortable in the green jacket, Woods took a call from President Bill Clinton, and later described it as if it were a chat with one of his buddies.

“He just said he was proud of the way I played,” Woods said. “He also said, what meant a lot, the best shot he saw all week was the shot of me hugging my dad.”

Even though the final round was a foregone conclusion well before Woods even got to the course, it was riveting. Nobody could take their eyes off the proceedings. And it sparked even more interest in Woods and what he would do next.

Nobody knew what was coming, but they certainly would be glued to their televisions, as golf ratings soared whenever Woods played. A commitment to a tournament meant an almost-automatic run on tickets, with tournament organizers scrambling to add concession facilities, parking places, grandstands, hospitality options, and security. It was wild. And it virtually never subsided, no matter when and where Woods played.