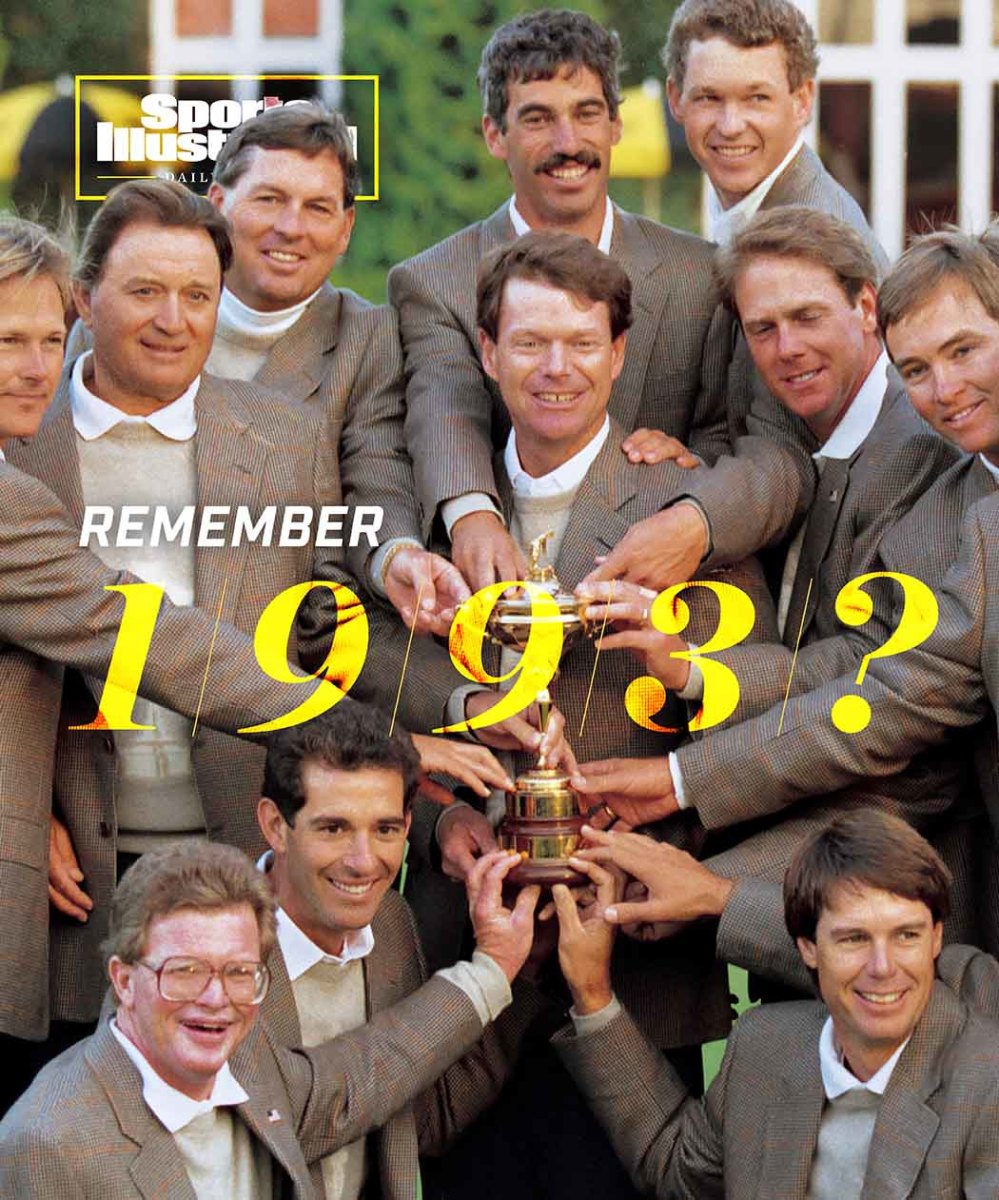

The U.S. Ryder Cup Team Hasn't Won a Road Ryder Cup Since 1993. Here's How It Happened.

The dearth of victories defies description. But there are several ways to highlight the U.S.’s 30-year drought of Ryder Cup wins on European soil.

- Five members of the U.S. Ryder Cup team were yet to be born.

- Tiger Woods was attending Western High School in Anaheim and had just captured his third consecutive U.S. Junior title.

- The Concorde was still in use.

The Concorde! Yes, the supersonic jet was just weeks away from being retired in September 1993 when the U.S. Ryder Cup team boarded the sleek vessel in Washington, D.C., after a stop at the White House for what was a high-speed flight to England for the 30th Ryder Cup.

“I remember just taking off,” says John Cook, an 11-time winner on the PGA Tour who was playing in his first Ryder Cup that year. “It was like, Oh my God, we’re in like a little rocket ship. It went straight up and then leveled off and was really cool. The flight took only about three and a half hours compared to the eight or nine it would normally take. We were way up there and going really fast. And the service was incredible, first class.”

Cook got a key point in a Saturday match with Chip Beck against European stalwarts Nick Faldo and Colin Montgomerie. Trailing by a point heading into the final-day singles, the U.S. managed six victories and three ties to pull out a tense 15–13 victory.

It was the last time the U.S. Ryder Cup team won in Europe.

Six times since that victory, the Americans have ventured to Europe, often as the favorite, and failed to claim the Cup.

Yeah, it’s been a while.

“Hard to imagine,” says Lanny Wadkins, a member of the World Golf Hall of Fame who played in eight Ryder Cups and captained the 1995 team. “I can’t fathom it’s been that long. Particularly with the quality of teams we’ve had going over there.”

A decade earlier, England’s Tony Jacklin had helped transform the Ryder Cup from a sleepy, lopsided affair into a heated, can’t-miss event. He went 2-1-1 in four turns as captain, winning the first Ryder Cup for all of Europe in 1985, taking the first victory in America in ’87 and then retaining the Cup with a tie in ’89.

The U.S. had won in 1991 at Kiawah Island in the cringeworthy “War by the Shore,” and now the competition was back in England—the third consecutive European match being played at The Belfry—with Tom Watson as the U.S. captain.

For the first time, the event was being televised live in the United States.

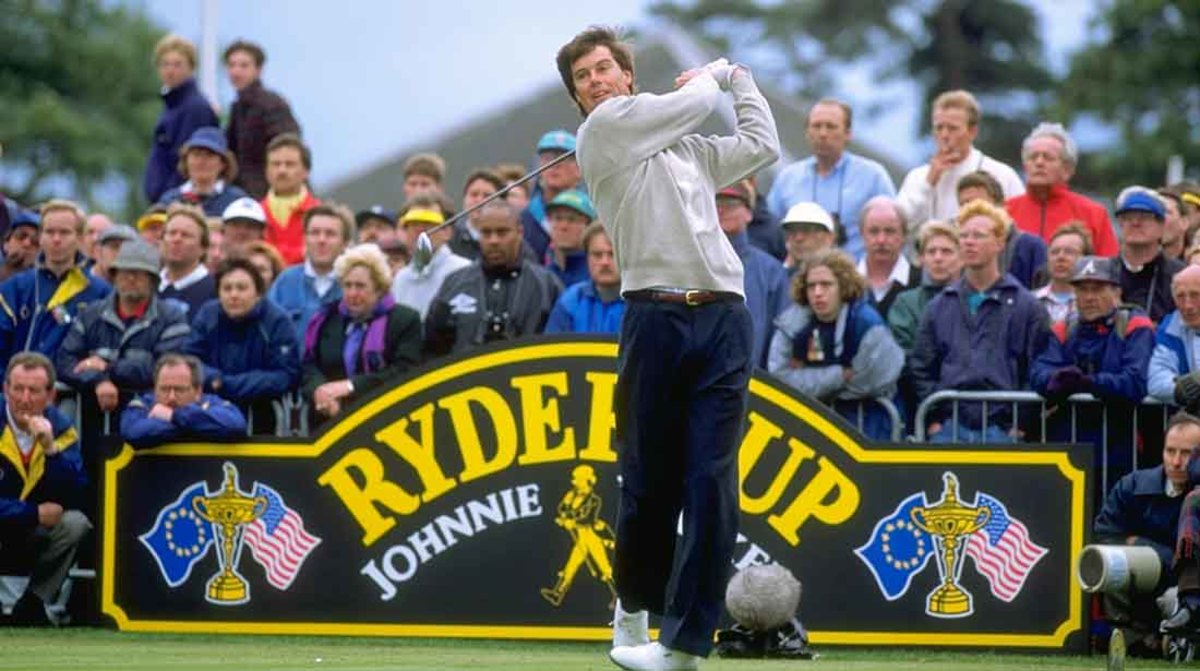

The Europeans had a group of players who had emerged as some of the best to ever play: Faldo, Montgomerie, Seve Ballesteros, Bernhard Langer, José María Olazábal and Ian Woosnam, along with Sam Torrance and Mark James.

The Americans had Paul Azinger, Fred Couples, Payne Stewart, Tom Kite, Lee Janzen, Raymond Floyd and Wadkins—all major championship winners to that point—along with Davis Love III, Beck, Cook, Corey Pavin and Jim Gallagher Jr.

How long ago was it? Phil Mickelson had yet to play in a Ryder Cup, going on a run of 12 consecutive starting in 1995. But his longtime caddie, Jim “Bones” Mackay, was there, too, sort of on a whim.

“I had always wanted to go to one,” says Mackay, who ended up caddying in 11 Ryder Cups for Mickelson and will be working for Justin Thomas this week. “And when you haven’t been, you’re not sure you ever will, even though at that time I was caddying for a top player like Phil.

“Phil had done pretty well but didn’t get picked, and I had some money, so I flew over to Birmingham, England, found my way there, went out to the golf course for one of the practice rounds. I probably wasn’t there an hour before somebody asked me if I could do something.”

These days a Ryder Cup team features several vice captains to help with various tasks during the week. But on Mackay’s first trip captain Tom Watson had brought along only one assistant.

“Whether it was ‘can you grab my rain jacket to get a dozen balls?’ I was pressed into service,” Mackay says.

Mackay had a friend in caddie Joe LaCava, who gave him a place to stay in his hotel room. LaCava was working for Couples.

“On the first day, there was a fog delay,” Mackay says. “The players had already warmed up. We go into the team room and we’re going to wait this out, and when the fog lifts we’re going to go. For the players, they’re already nervous. All the bags were stacked up on this marble floor next to a staircase, and Fred was going through guys’ bags. He took an 8-iron out of Davis’s bag and was waggling it … and the head fell off the shaft and bounced on this staircase. It was like a Saturday Night Live skit.

“A matter of minutes later, they announced that it was just five minutes until we’d start. Tom Kite and Davis Love [were in the third group out]. And Davis hands me the 8-iron and says, ‘Get it fixed.’

“There were no [equipment] trucks like at major golf events now. But there was a guy who had a little pickup truck across a couple of fields. And he had some epoxy, and I ran across the field and got this club fixed for Davis. And got it to him midway through the first hole.”

Throughout the competition, Azinger’s right shoulder was bothering him. It had been giving him discomfort for months, but he was playing some of the best golf of his life. He won the PGA Championship in a playoff over Greg Norman. He won earlier that year at the Memorial—holing a 72nd-hole bunker shot to defeat Stewart—and he also won the New England Classic.

Azinger’s doctor, Frank Jobe, wanted to perform a biopsy. But Azinger dealt with the pain in winning the PGA. He was playing well and wanted to continue, waiting until after the Skins Game in November to have any testing done.

“I was hurting [on] the final day,” says Azinger, 63, who will be at Marco Simone Golf Club as an analyst for NBC. “I knew something was up. It never affected my swing. [The pain] was on the back of my shoulder. So if you patted me on the shoulder, you’d hit the bone. It was painful enough. I didn’t let anybody touch me there. And I was conscious of it. It just throbbed on and off.”

A few months later, Azinger was diagnosed with a form of cancer called non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He underwent treatment for more than a year before returning to defend his PGA Championship title in 1994.

Azinger and Stewart played Woosnam and Langer in Friday morning foursomes and were waxed 7 and 5. And that’s when something occurred that makes Azinger chuckle today: He was paired with Couples in an afternoon four-ball session against Faldo and Montgomerie.

“Freddie and I didn’t play practice rounds or anything,” Azinger says.

Their match ended up being postponed due to the darkness stemming from the fog delay, so they had to finish Saturday morning.

“It was so cold, and we were both underdressed,” Azinger says. “Freezing cold. Somehow on the last hole, I skanked it up there and I putted it up to about 20 inches or so. Maybe 2 feet. And it must have been Monty who gave it to me because it damn sure wasn’t Faldo. If he’d have known how cold it was and how hard I was shivering, I’m not sure he’d have given me that putt. And I wouldn’t blame him. I don’t know if I could have made it. Unbelievable.”

Azinger and Couples got a half point out of that match but lost both of their matches together later that day, meaning the U.S. trailed 8½ to 7½ going into the 12 Sunday singles matches.

Cook made his first U.S. Ryder Cup team despite not winning in 1993. He had finished in the top six three times in his previous six major championships, however, and was second at the ’92 Open to Faldo. He was seventh in points to easily qualify for one of the 10 automatic spots, with Wadkins and Floyd the captain’s picks.

And so it came as a bit of a surprise to Cook when he sat out the entire first day.

“I’m kind of wondering what the heck is going on,” he says. “It wasn’t like I was a pick. I made it on points and I was disappointed not to play the first session and the second session. And I felt I made a pretty good foursomes partner. Then the pairings come out for Saturday morning, and I’m not on it, nor is Chip. What in the world?”

It was even more bothersome as the Americans were getting spanked. They lost three of the four matches Saturday morning and trailed 7½ to 4½.

“I was wondering if I was going to play at all,” Cook says. “Then midway through the session in the morning, I was up on the practice tee, hitting some balls, and Watson said, ‘O.K., I’ve got a feeling about you two. Are you ready?’ ‘Yeah, we’re ready.’ Then he tells us we’re playing Faldo and Montgomerie [in the first match of the afternoon] and good luck. So here we get thrown to the wolves. It’s my first Ryder Cup experience, but I was ready to go. I was so jacked up to go play.”

Cook made a 20-footer to tie Faldo with a birdie at the first hole, and both teams also birdied the fourth before the Europeans went ahead at the sixth hole. But the U.S. tied with a birdie at the seventh and then took the lead when neither Faldo nor Montgomerie could make par at the eighth.

The lead stayed 1 up all through the 18th hole, where Cook knocked his approach close for a birdie and a huge 2-up victory.

“I do remember on the 18th on Saturday evening I hit a 4-iron in there like 4 feet,” Cook says. “One of the best shots I’ve ever hit. Lanny was out there watching, and he gave me this big hug. Faldo hit it in the bunker, and Chip was on the green. I remember walking down the path and Lanny being the first to come up and congratulate me. I will never forget that. He and Floyd were captain’s picks, and they could not have been any better. It was just a great mix of veterans and rookies.”

Heading into Sunday, Wadkins was involved in one of the more odd and uncomfortable parts of the Ryder Cup: the envelope.

If a player cannot compete due to injury, he is not allowed to be replaced. That’s not an issue during the team matches when four players sit out each session. But for the final day, all 12 compete. What if someone is sick or injured?

Instead of forfeiting the match, the Ryder Cup has a system where each captain puts the name of a player in an envelope that is never revealed. If the other side has a player who is injured, the player in the envelope sits, and each side is awarded a half point.

There has always been an undercurrent of mistrust in the process. Is a player who is not in the best form claiming injury to at least secure a half point? Or is he unwilling to play through an issue that would not prohibit him from competing any other week of the year?

It’s something no captain wants to encounter. It means telling one of your players that you have to sit him, thus insinuating he is the weakest on your team.

It’s happened only three times in Ryder Cup history. In 1979, England’s James could not play due to a chest injury, so Gil Morgan sat out for the U.S. In ’91, Steve Pate had been involved in a car accident leading up to the Ryder Cup and played in the afternoon session Saturday. But he was deemed unfit for singles, so David Gilford ended up sitting for the Europeans.

“I talked Tom into putting my name in the envelope,” Wadkins says. “I had played three times. I was a captain’s pick. And so I was fine with it. Then the lineup comes out, and I’m supposed to play Seve. I was 4–0 against him over the years, and I really wanted to make it 5–0.

“Then they tell us Torrance can’t go. He had a septic toe or something like that, a foot injury. And he couldn’t play. So Jim Gallagher got moved into that spot.”

Because both sides were awarded a half point, the competition stood at 9–8 in favor of Europe. The U.S. needed six points to retain the Cup, while Europe needed 5½. (As the winner of the 1991 Cup, the U.S. needed only a tie to retain.)

The first match was tied between Couples and Woosnam. Beck, who had played only in the Saturday afternoon four-ball match with Cook, prevailed over Barry Lane 1 up, rallying from three holes down with five to play, putting the U.S. just 4½ points away from winning the Cup.

But Montgomerie (1 up), Peter Baker (2 up) and Joakim Haeggman (1 up) rattled off consecutive victories to pull the Europeans within four points of the win.

Gallagher, who was 1–1 in his two previous matches, never trailed against Ballesteros, losing just two holes and giving the Americans a big boost as he was 4 up on the back nine and clearly on his way to a win. He prevailed 3 and 2. With Stewart having defeated James 3 and 2 and Kite leading easily and posting a 5 and 3 victory over Langer, the U.S. was just 1½ points away from clinching the Cup.

Floyd, who had captained the U.S. team to its 1989 tie at the same venue, forged ahead, birdieing three consecutive holes to take a 3 up lead over Olazábal, before seeing it cut to 1 up with two to play and then finally winning on the 17th hole, 2 up.

That meant the U.S. needed just a half point. But there were two close matches on the course. Azinger was 2 down to Faldo through 10 holes, and Love was trailing by one hole with three to play against Costantino Rocca. If the Europeans were to win both matches, they’d capture the Cup.

But Azinger overcame an ace by Faldo at the 14th hole and eventually earned a half point with a birdie at the 18th. Love’s match was the actual clincher as he won the 17th and 18th holes with pars to prevail 1 up. The final score was 15–13.

“Davis gave me a big hug after that,” Mackay says, recounting that Love’s 8-iron played a key role that day. “‘That was the club you got fixed.’ Pretty incredible experience for me.”

Azinger knew by the time he got to the 18th tee that the U.S. had clinched, but he still badly wanted that half point against Faldo—who defeated him by a stroke at the 1987 British Open while parring all 18 holes.

“Once I lost the British to him, for me it was always a grudge; I don’t think there was one for him,” Azinger says, laughing. “When I won the PGA, I beat Norman in a playoff, and Faldo had his chance there, too, but the Ryder Cup … it was just the little things like that.

“And we later worked together [at ABC] and worked well, no question about it. Nothing but respect now. But we were all just trying to achieve as much as we could for the history books. That’s what we were shooting for.”

Nobody can pinpoint exactly why the United States has struggled so much to win in Europe over the past three decades. Poor play, dubious captain’s picks and lack of team unity have all been cited.

You can also point to bad luck—the fine line there can be in the Ryder Cup—and certainly the fact that the Europeans have been formidable foes now for four decades.

The U.S. lost close matches in 1997 (14½ to 13½), 2002 (15½ to 12½), ’10 (14½ to 13½). The ’06 defeat tied the worst for the Americans, and ’14 and ’18 were lopsided losses as well. Only Europe in ’12 (the Miracle at Medinah) has won a “road match” going back to ’04.

Wadkins scoffs the individual vs. team reasoning that has been often cited.

“I don’t understand how that’s ever an issue,” Wadkins says. “Most of our guys knew each other well. Guys I got to know better at Ryder Cups. They’ve got people from other countries. How are guys who are speaking Italian, speaking Spanish, speaking German ... their cultural barriers are worse than ours. I never bought that at all. I thought it was a crock.”

Cook also says the “team” issue has been overplayed but wonders whether the Europeans did have a better plan.

“Maybe the European team for a number of years just got fired up to play us,” Cook says. “The U.S. players didn’t come together as a team? I find that hard to believe being part of it. Once you are a part of it, you can’t not become a team. We all bought in, so I have a hard time believing that in all those years they ended up losing because they didn’t buy into the team thing. I don’t understand.

“Maybe it was the system. Azinger kind of changed that a little bit [with his pod system in 2008] and maybe they started gaining more momentum. It always seemed like the Europeans had a captain in waiting, a captain in training. You knew the lineage of who the next captains were going to be.”

Ironically, it was Watson’s second captaincy in 2014 and the frustration of another loss that led to Mickelson’s infamous Sunday night criticism of the system and Watson, in particular, that led to changes that now see a succession plan in place.

But back in 1993, nothing like that was happening. Captains were picked by the PGA of America as sort of a career achievement honor. Watson, an eight-time major winner who played on four U.S. Ryder Cup teams, was certainly deserving. And nobody had an issue with the way he did things then.

Now, Zach Johnson was basically picked by the players. His road to the captaincy began when he was an assistant to Jim Furyk at the 2018 Ryder Cup. He then assisted Woods the following year at the Presidents Cup, again with Steve Stricker at the ’21 Ryder Cup and last year with Love at the Presidents Cup.

He’s also seen all the various team combinations and had help from previous captains who are now his assistants, including Woods—who is doing his work from afar. Johnson’s pick of Thomas this year has been controversial, but it was likely part of a bigger picture, one that sees more planning, more of a system for matching partners.

In the end, it comes down to playing well. Although the Ryder Cup has had some lopsided outcomes in recent editions, it’s usually a fine line between winning and losing 18-hole matches. Captains probably get too much credit for winning, too much blame for losing.

All of which is to say things will be decided on the Marco Simone Golf Club course.

And if the U.S. team does prevail, it can take comfort in a nice, long celebratory trip home. It won’t be on the superfast Concorde, which in this case, will be a good thing.

More Ryder Cup Perspective:

- Norman, who lost in a playoff to Azinger at the PGA, had won the British Open that summer of 1993 at Royal St. George’s, his second and last major championship.

- Norman was ranked No. 1 in the world, Faldo No. 2 and Azinger the top American at No. 5 at the time of the 1993 Ryder Cup.

- And Floyd, who is now 81, was a 51-year-old captain’s pick at the 1993, becoming the first player—and last—since Arnold Palmer to play in a Ryder Cup after having served as captain. (Palmer was a playing captain in ’63 and played in four more afterward before being captain again in ’75; Floyd was the captain for the ’89 team.) He also remains the oldest to compete in the Ryder Cup.

30 Years of Ryder Cup Road Woes

1997: Valderrama, Spain 14.5-13.5

Lowlight: Tiger Woods went 1-3-1 including a singles loss to Costantino Rocca.

2002: The Belfry, England 15.5-12.5

Lowlight: The U.S. earned 4.5 points out of 12 in Sunday singles.

2006: The K Club, Ireland 18.5-9.5

Lowlight: Europe matched its biggest winning margin, set two years earlier at Oakland Hills.

2010: Celtic Manor, Wales 14.5-13.5

Lowlight: The event was plagued by rain, and the Americans’ rain jackets infamously failed.

2014: Gleneagles, Scotland 16.5-11.5

Lowlight: A testy post-Cup press conference led to the formation of U.S. Ryder Cup task force.

2018: Le Golf National, France 17.5-10.5

Lowlight: Tiger Woods and Phil Mickelson went a combined 0–6.