Bells Ring True at Torrey Pines

With the U.S. Open returning to Torrey Pines for the second time, it’s understandable that the spotlight should shine on architect Rees Jones, who remade the South Course into a major-worthy layout. Unfortunately, the heightened focus on Jones further diminishes the credit that rightfully belongs to the original architect of Torrey Pines, William P. Bell — or more correctly, his son William F. Bell. Let’s right that wrong.

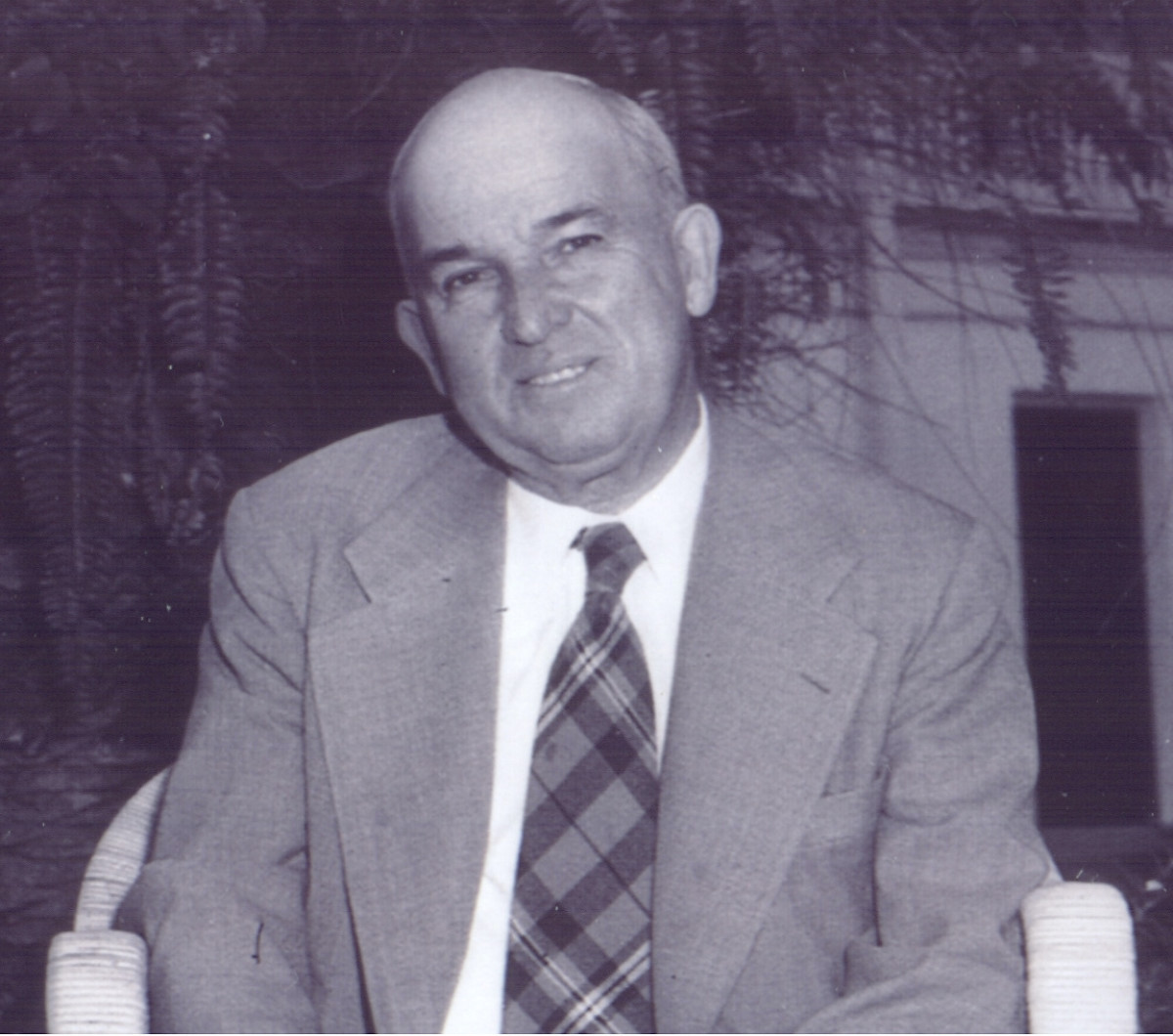

William Park Bell was a significant West Coast figure in the Golden Age of Design, flourishing from 1920-1930, and again after the Depression. He enjoyed a final run after World War II, when his son William Francis Bell joined him in the practice. In total, the Bells designed or redesigned more than 300 courses in 10 states, an astonishing number by any measure, one exceeded by only a handful of other practitioners.

How is it, then, that the Bells aren’t better known? It’s complicated.

Pennsylvanian William P. Bell (known mostly as Billy and then later as Billy Bell Sr.) relocated to Southern California in 1911 at age 25. Bell first stopped at Annandale Golf Club in Pasadena as caddiemaster, followed by a stint as head greenkeeper at Pasadena Golf Club (now Altadena Golf Course). In time, he began to assist the West Coast’s most prominent architect, William Watson, serving as construction superintendent, before launching his own design practice in 1920.

Among Bell’s greatest surviving solo designs are Stanford University Golf Course (1930), Brookside Golf Club (1928), La Jolla Country Club (1927), Woodland Hills Country Club (1925), all in California, and the Arizona Biltmore Country Club’s Adobe course (1928). What he was best known for, however, were his 1920s collaborations with architect George C. Thomas Jr., most notably on Riviera, Bel-Air and Los Angeles Country Club.

Part of why Bell isn’t more lauded as a Golden Age great is that his contributions to these elite layouts have been obscured over time. Back in the day, however, Thomas was quick to credit Bell. In his seminal 1927 book, Golf Architecture in America: Its Strategy and Construction, Thomas stated, “In most of my California work I have had William Bell, of Pasadena, in charge of construction, and to him I owe much of the success of what I have done. A fine architect himself, Bell has always been loyal to me. He has gone far and will go further in golf construction.”

Bell was acknowledged as a master bunker builder, his best work displaying elaborate shaping and intricate edging. A highly skilled router of golf holes, he also excelled at taming difficult sites with engineering and drainage feats that were extremely sophisticated for the time.

Perhaps the biggest reason why elite status has eluded Bell revolves around his missing courses. As a solo designer, he created some of most inspired, spectacular layouts in the history of Southern California golf. Yet, due to the Depression and community expansion, many of those courses were plowed under. Most tragic of all was the rapid demise of Royal Palms in San Pedro, on the edge of the Palos Verdes Peninsula in Los Angeles.

Built in 1927 and gone by 1933, Royal Palms was truly sensational. According to historian Daniel Wexler, it consisted of “350 clifftop acres situated above a secluded section of Pacific Ocean beach, its entire spread offering unparalleled views across the San Pedro Channel to Santa Catalina Island.” Its edge-of-the-cliff, 442-yard, par-4 18th hole, “immediately challenges one to name a tougher or more memorable finisher of the pre-war era,” wrote Wexler. Had Royal Palms prospered, perhaps Billy Bell would have been as famous as Ross, Tillinghast, MacKenzie and Thomas.

William F. Bell, often called Billy Bell Jr. or just Junior, joined his father after World War II. Together, they crafted more than two dozen new designs from 1946-1953, including Tucson Country Club, Mesa Country Club and Yuma Golf and Country Club in Arizona and Tamarisk Country Club, Newport Beach Country Club and Palo Alto Muni in California.

Upon his father’s death in 1953, Junior honored him by re-naming the design firm, William P. Bell and Son. It was perhaps a shrewd marketing move as well. Billy Bell Jr. became even more prolific than his dad, designing more than 200 golf courses throughout the west. While he never could match his father for artistry and innovation, he gifted golf with fistfuls of acclaimed layouts, including Papago in Phoenix (1963) and California courses such as Sandpiper (1972), Bermuda Dunes (1960) and Industry Hills (1979).

Current ASGCA President Forrest Richardson of Richardson-Danner has extensive experience with Bell creations. “I’ve been to at least 50 different William F. Bell courses,” Richardson said. “When he had a good site, he did good work.”

So which Bell rang at Torrey Pines? It’s complicated.

The elder Bell contracted with the city of San Diego in 1950 to submit a plan for a city-owned 18-hole course in the Torrey Pines vicinity. However, approval for the final plan — 36 holes, incidentally — didn’t occur until 1955, two years after he passed away. It was the younger Bell who actually designed the North and South courses, but under the auspices of William P. Bell and Son. Therefore, “Senior” had a role in Torrey’s creation, but not in the final design.

Although dad didn’t figure in Torrey Pines’ design, it’s possible that mom did. Architecture historian Tommy Naccarato, who is frequently part of Gil Hanse’s design team, remembers a chat he had in the late 1990s with management at Los Coyotes Country Club, an L.A.-area, 27-hole William F. Bell design from 1958. An anecdote passed down from the previous owner was that apparently Bell returned years later for a consult and brought along his mother, Anna. After a bit, Anna excused herself. The owner said, “It’s interesting that you brought your mother.” Whereupon Bell replied, “I don’t think you understand. We’re partners. She used to help my dad with all the routings.”

A heart attack took the life of William P. Bell in Pasadena. Remarkably, Billy Bell Jr. was similarly fatally felled, also in Pasadena, in 1984, at nearly the same age. Both deserve more lasting renown.

At the very least, says Richardson, they made up “unquestionably the most prolific family of California golf architecture.” As legacies go, that’s a strong one.