How Boise-area girls basketball standout keeps memory of late mother alive and well

EAGLE. Idaho - Molly Johnson’s mom is always with her.

The Eagle High senior guard talks to her before every game. She even points her out to the crowd after every one of her made free throws.

There was a time when multiple sclerosis - a chronic disease where the immune system attacks nerves resulting in the loss of motor functions - prevented Alice Johnson from attending any of her youngest child’s games. But now, nearly five years after the incurable disease claimed the elder Johnson's life, she now has the best seat in the house.

“I think it’s so beautiful. I learned so much from her,” Molly said. “How do I not be the best that I can be when I have two lives weighing on me?”

* Alice was a college graduate - a Camilla Eyring Kimball Scholar, which is one of the top scholarships given out at BYU every year

* Alice was top executive for an international consulting firm, working for Monitor Deloitte, which currently has more than 6,000 employees around the world.

* Alice was a musician - and by all accounts, had a beautiful singing voice. She also taught herself how to pay the piano and cello. And she composed her own music.

But Molly was too young to remember any of that.

By the time Molly was age 3, her mother had lost her ability to sing and play a musical instrument.

Three years later, her mother was in a wheelchair.

And by the time she turned 10, Alice was bedridden.

“The ones (memories) that I do have, they’re still tainted, of course, with the disease,” Molly said. “But the times that we spent together were still so fun.”

They included learning how to read.

Alice wasn't able to do many activities back then. Writing was one of them, and she often laid in bed penning her latest novel. And as she was doing so, Molly regularly grabbed a book and laid right next to her.

As Molly entered her teenage years, Alice's body had deteriorated to the point where she was unable to attend games in person anymore. Instead, she would just watch footage that her husband, Paul, recorded on his phone.

“I feel like that would affect anybody in some way, and looking back, I’m sure she wishes her mom could have been to all her games,” said Rocky Mountain High girls basketball assistant Alycia Osterhout, who was Molly's club coach back then with the Boise Slam.

“But I feel like they made the best out of it. She’d set up the iPad with her mom and she got to relive the game again. I just thought that was sweet. It was their thing to cuddle together on the bed and watch her game."

The whole Boise Slam team got to experience that bond when the end-of-season party was held at their house in 2019.

“She obviously wasn’t ready for us to meet her until then,” Osterhout said. “We all took a picture with her. It was a really sweet experience.”

Three months later, Alice died in May. She was 55.

One of Molly's difficult realizations from her mother's 20-year battle with multiple sclerosis (MS) was that Alice's decision to have children likely shortened her life.

“When I really think about it I’m like, ‘Oh man, that’s crazy,'" Molly said. “Kids are always posting videos saying their moms are the greatest. But I’m like, ‘No. Did your mom die for you?’

“Maybe she’d still be here if she hadn't had me. I’m grateful to my siblings because they lost years with her because of her choice. There’s nothing that is more motivating than that for me. How can I ever sit and just be stagnant and mediocre? Why would I ever accept that?”

And she hasn’t.

Even sometimes to her detriment.

Molly knowingly played all of last year with a torn labrum. But it never slowed her down.

She helped the Mustangs end a two-year postseason drought with a 48-39 upset of Lake City in the state play-in game. The Timberwolves spent a good part of the year as the top-ranked team in the state. Molly guarded one of their key players in Sophia Zufelt, who finished below her season average with 10 points that game. Molly was the game’s second-leading scorer with nine points herself.

She then nearly helped Eagle pull off another stunner five days later on a sprained ankle. The Mustangs had a 10-point lead late in the third quarter against No. 1 seed Coeur d’Alene before falling to the eventual state champion.

Molly earned all-5A Southern Idaho Conference honors that season.

“That tells you everything about her toughness, both physically and mentally,” Eagle girls coach Jeremy Munroe said. “I admire her as a person and as a player You take in those moments where you get to coach a kid who’s as rare as she is. You just sit back and you enjoy it.

“She never wavers.”

Even in the darkest of times.

Molly admitted she never really grieved when her mom died. It wasn’t until sophomore year when it hit. And it was triggered by just a friend asking Molly who was on her phone case.

But that’s not what did it.

It was the apology afterwards and the friend revealing that she had lost her own mother at a young age as well.

“It woke me up,” Molly said.

Molly then had a tournament in Coeur d’Alene. Eagle went 0-3 and Molly started bawling. It wasn’t the losses. But watching everyone else receive hugs from their moms.

“I was feeling things that I had never let myself feel,” Molly said. “I had never thought about these kinds of things.”

It’s still difficult today.

Particularly when things like homecoming or prom come around. Molly was this year’s homecoming queen.

“I’ve lost my grandparents and that was hard. But I can’t even imagine losing a parent,” Osterhout said. “To lose a mom at that age in those prime teenagers, she’s a tough kid. I just praise her because I don’t know what I would have done.”

Basketball helps.

Especially during the MS awareness game that the Mustangs have put on and raised more than $5,200 with in the past two years.

“She did that 100% on her own. It was her idea. She took it and ran with it and got the administration and the team on board,” Paul said. “It makes me so happy to see that love and desire to give back and help find a cure so other kids don’t have to go through what she’s experienced and others don’t have to go through what her mom experienced.

“She did it really all out of love for her mom, which is just beautiful.”

This year’s game was against Centennial in mid-December. Molly scored the game’s first points on a corner 3-pointer right in front of her entire family.

She finished with a season-high 20 points and five assists in the 54-35 win.

“Honestly, it was one of those things that you know there’s something there. There’s something to it,” said Munroe, whose grandmother died from MS. “She’s just such a great kid and you know that someone or something was there. She carried it in such a positive way. She deserved that night.”

As well as being on stage with country music star Zach Bryan last August.

Molly was sitting in her Bronco in the driveway last year when his song, “She Alright” came on. The song is about Bryan’s late mom, who died in 2016.

“The first time I heard it I absolutely sobbed,” Molly said. “It was so relatable.”

Molly already had tickets to his concert. But the song wasn’t on the set list. So she busted out her own guitar and recorded herself playing it. She uploaded the video to TikTok and tagged him in it as a concert-lineup addendum request.

Molly posted a new video of her playing the same song for 175 days in a row.

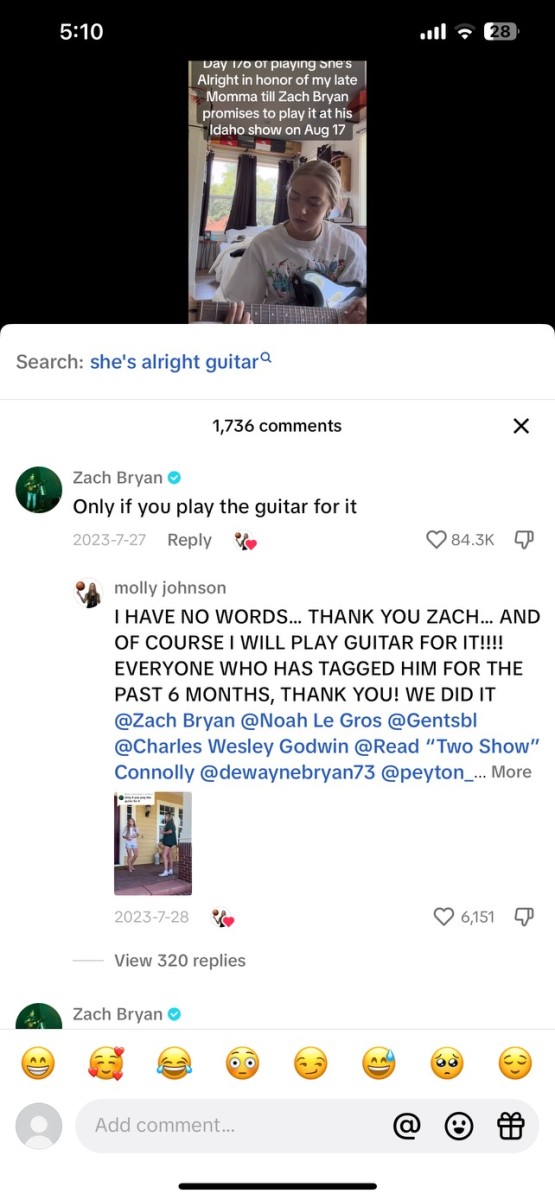

And on Day No. 176, he finally responded.

Only she wasn’t the first to see it.

Her sister woke her up at 7 a.m. She was demanding her phone. Molly eventually relented and went back to sleep.

Molly woke a few hours later and was told to get dressed. She came downstairs and noticed that the front door was open. Molly walked out and saw her entire family had their cellphones out. They handed her back her phone and told her to go to the comments.

“Done," Bryan replied.

“Only if you play the guitar for it.”

“That’s just what Molly does,” Osterhout said. “Because what kid would do that? I can’t even see my own kid trying to do something like that. “ But that just tells you Molly’s persistence, her love, her passion and if she wants something, she goes for it.”

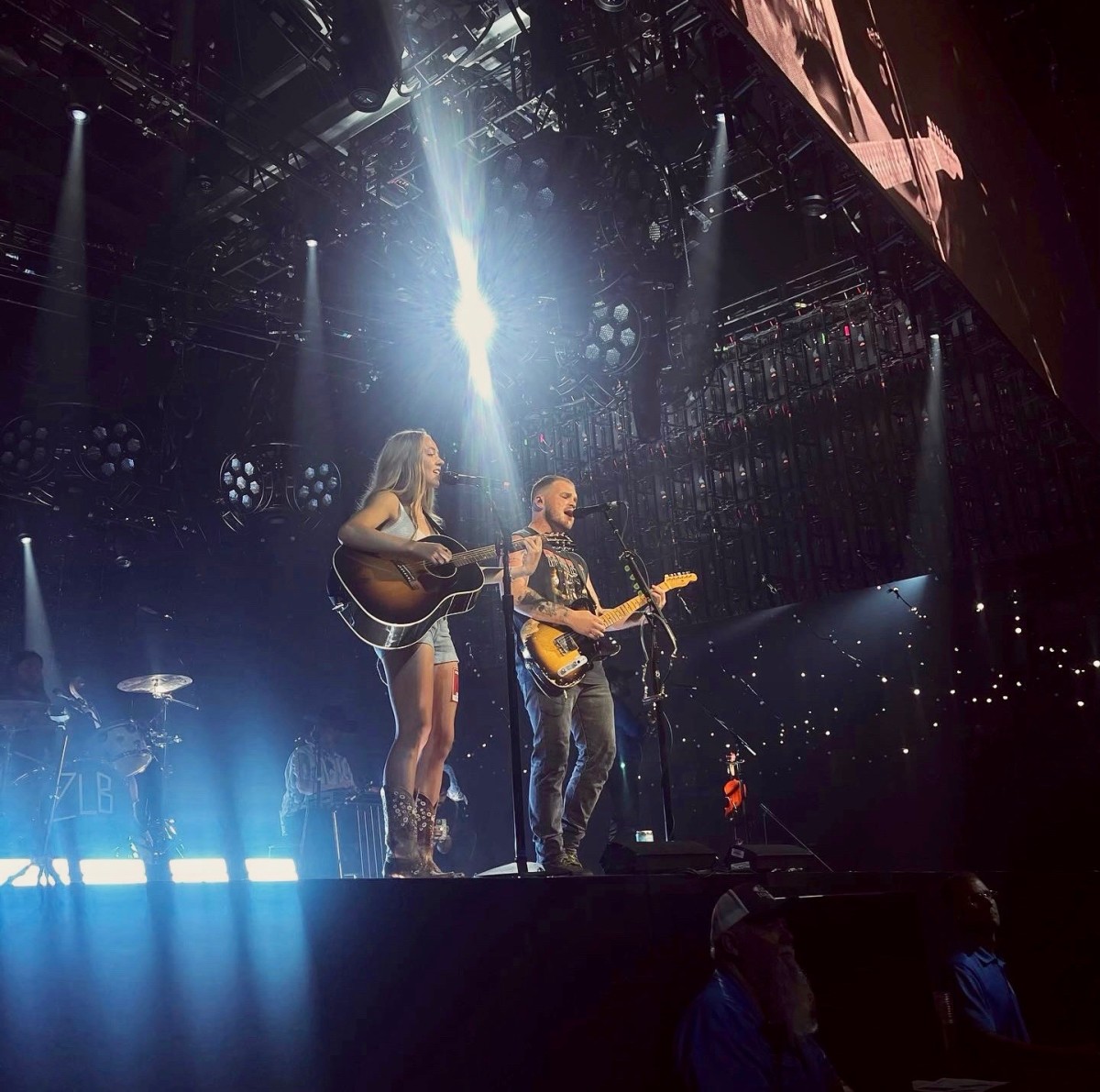

So on Aug. 17, Molly was called on stage to perform in front of one of the largest crowds in the history of the Idaho Center Amphitheater. There were more than 10,000 people in attendance that day.

“One-hundred percent, I could feel her there,” Molly said. “I swear to you the instant my foot hit the top of the stage, I've never felt so calm and ready to perform. And I mess up on guitar all the time. But there was so much heavenly help with not letting those nerves get to me.”

She also went to his rehearsal earlier in the day, got a photo, an autographed guitar and a little personal one-on-one conversation with him.

“Zach had known me for like two hours, but I felt like he was proud of me,” Molly said. “He lets me start it and he’s supposed to come in and sing. But I didn’t realize it until I saw the video where he just steps back and is smiling.”

“The only way to explain it is I don’t deserve this.”

Only she does.

Molly just signed to play basketball at Walla Walla Community College in Washington. And Alice will be with her there, too.

Whether it’s during Molly’s pre-game prayer or her free throw routine where she taps her chest and points to the heavens.

She’s always with her.

“I take so much strength in that,” Molly said. “I think she could affect the ball going in if she wanted to. So I have this extra power that I don’t think other kids get for sure. It does suck that there’s some memories that I’m not going to get. But I think there’ll be time to make up for it.”